Following the downgrades of Greece (to junk) and Portugal (to A-) on Tuesday, S&P looked upon the carnage in sovereign bond markets that ensued and decided that on Wednesday it would be Spain’s turn. Spain’s sovereign credit rating was cut from AA+ to AA, just a notch, but enough to send its CDS spread up above 200 bps, and to see the credit spreads on its banks widen by 20 bps or more for senior bonds.

Whilst we know that fiscal positions in peripheral Europe are poor, and deteriorating, the worry is that the biggest input into the decisions to downgrade was the movement in bond prices. In other words, credit ratings were cut because the bond prices had fallen. To some extent this is rational – as interest costs rise with higher government bond yields, creditworthiness falls. The rating agencies have explicitly talked about this, for instance when Moody’s cut Greece’s rating earlier this month it said that “there is a significant risk that debt may only stabilize at a higher and more costly level than previously estimated”. In the high yield market the fall in the rating agency default forecast from 20% in 2009 to below 5% has been largely driven by lower junk bond spreads, not an improvement in revenues or profits.

But it does make you wonder what the point of the rating agencies is – if their ratings are largely reflecting what the bond market is telling them, who needs them? Isn’t the real information simply the price? The problem is that the rating agencies remain important; pension fund mandates include triggers forcing them to sell below certain ratings, and even the ECB has limits on the collateral that it will accept into its money market facilities based on the official credit ratings (currently junk bonds are excluded, although Greece still has investment grade ratings from other agencies so its debt remains eligible). The BBC’s Robert Peston has blogged this morning about the power of the credit rating agencies – I have less concern about the power, than the usefulness of ratings as investment information.

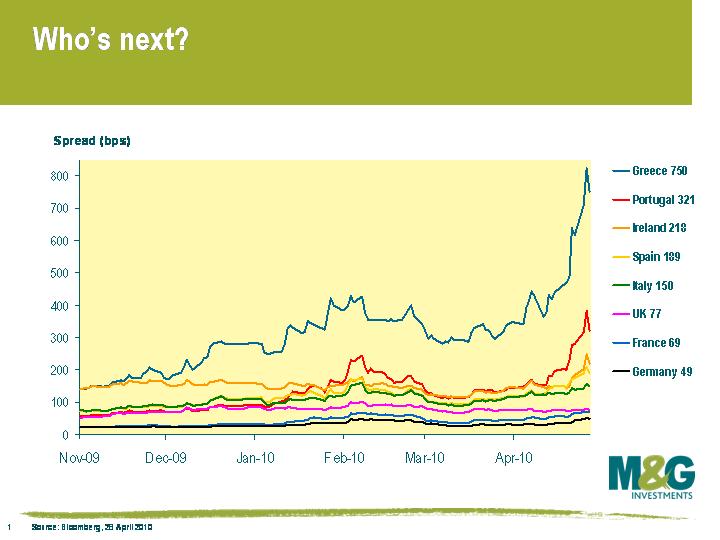

What’s the CDS market saying now about sovereign credit risk if we think that it’s a predictor of credit ratings? Greece’s junking by S&P was long overdue, and as at yesterday’s close, the cost of insuring Greek debt was higher than insuring Pakistan (B-) and Ukraine (B-) and only 100bps less than Argentina (B-). Portugal (A-) closed at 321bps, putting it between Latvia (BB) and Lebanon (B). The market is implying that Ireland’s AA rating is very vulnerable given that based on CDS of 218bps it’s sandwiched between Croatia (BBB), Hungary (BBB-) and Egypt (BB+). Spain (AA rated, 189 bps) is between Kazakhstan (BBB-) and Turkey (BB). All the credit ratings quoted above are S&P’s – generally speaking the other agencies have been even slower downgrading sovereigns, considering that Fitch and Moody’s still rate Spain AAA/Aaa respectively!

Interestingly, as you can see from this chart, the UK looks very much like an AAA rated issuer. UK 5yr CDS is the closest it’s been to France since September 2008 (albeit this is more to do with French default risk gradually increasing). We don’t expect a UK downgrade – but if there is one, you might imagine it will come on the back of a gilt market sell off rather than precipitating one.

Finally and on a slightly different topic, a US economist, David Hale, made public a private remark made to him by Bank of England Governor Mervyn King – “he told me whoever wins this election will be out of power for a whole generation because of how tough the fiscal austerity will be”. Maybe yesterday Gordon Brown was playing the long game and deliberately trying to destroy Labour’s chances in next week’s General Election? You might well argue that politically, this is a good election to lose – it also means that the Conservatives won’t be too miserable if they end up having to rely on LibDem support as they can share the burden of several years of voter anger.

Exactly one year ago, an outbreak of flu in Mexico led to fears of a global pandemic. ‘Swine Flu’ did indeed spread around the world, however for most countries it had only a limited effect on economic output.

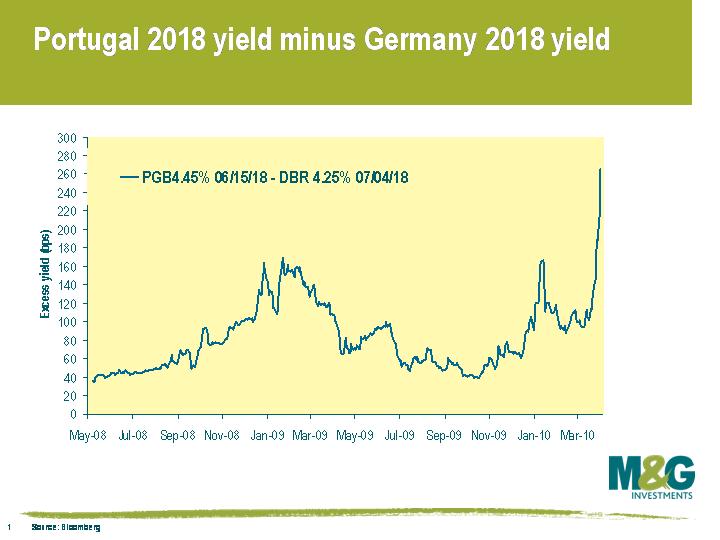

We are now facing something that is likely to prove much more serious. This time the epidemic can be traced to Greece, and contagion is rapidly spreading among the PIGS. At the beginning of April, Portuguese 10 year sovereign debt had an excess yield over German 10 year bunds of about 100 bps. Portugal began showing some worrying symptoms last week, but today things have got a whole lot worse. The attached chart shows the historical yield differential between a German and Portuguese sovereign bond maturing in 2018. The Portuguese bond was issued yielding 40 bps over the benchmark German bund, and today spreads over Germany have lurched to a sickening 260 basis points.

Who’s likely to get infected next? The other PIGS look particularly vulnerable, and Ireland, Italy and Spain are all spluttering today to varying degrees. Ireland has been worst hit, with its 10 year sovereign debt widening 20 bps+ versus Germany, equivalent to about a 2% drop in the bonds’ price. Italian 10y bonds are about 7bps wider, not helped by a weak auction earlier today, while Spanish 10 year debt is off about 5 bps.

But just as with the original swine flu, people may find that this disease can spread beyond the PIGS. Investors have (basically until today) seemed to consider EM sovereign debt to be immune, but Turkey 10y Euro denominated debt has sold off 7bps versus Germany (so it looks like birds can get it too). Meanwhile equity investors have seemed to be on another planet entirely, which may explain why the S&P 500 succeeded in closing at a 18 month high on Monday this week.

We’ve spent a lot of time debating what happens to credit markets if sovereigns continue to deteriorate. This is something we’ve been pondering for a while – see Stefan’s thoughts here from February last year – but sovereign indebtedness has gone from being a small risk to something that’s one of the very biggest risks, as the IMF recently highlighted. Can we have negative credit spreads, i.e. does a company like Telefonica potentially trade through Spain, or can GSK borrow at cheaper levels than the UK government?

We think this is certainly possible in stronger credits – in fact Johnson & Johnson short dated bonds already yield less than US Treasuries. But if the weaker sovereigns get into trouble, to what extent will, say, a high yield German cable company get affected if it only operates domestically…?

(Addendum: S&P has just downgraded Portugal two notches from A+ to A-, and Greece’s long term sovereign credit rating has been downgraded three notches from BBB+ to BB+. It’s all kicking off….)

Guest contributor – Vladimir Jovkovic (Credit Analyst, M&G Credit Analysis team)

By now we are all well aware of the economic problems that Greece faces. Certainly we have mentioned Greece a few times on this very blog. But let’s not forget that the Greeks have given the world many, many wonderful things. Democracy. The musings of Socrates (“I am not an Athenian or a Greek, but a citizen of the world”). Zorba’s dance. And centaurs!

In Greek mythology, the centaurs are a race of creatures composed of part human and part horse. Why is this relevant? Well, corporate hybrids are the centaurs of the bond world.

Corporate hybrids are bonds issued by companies that have features of both debt and equity capital, hence the term `hybrid’. Many readers would be familiar with the original hybrid security: preferred stock, representing ownership in a company (like equity) but having fixed payments (like bonds). Another example of a hybrid security is the convertible, however, here we are referring to non-dilutive corporate bonds which rating agencies assign equity credit to, and hence are different to both prefs and converts.

Like traditional bonds, these hybrid securities have fixed coupons and can be redeemed for fixed amounts. Like equity, they are subordinated to other types of debt and issuers can choose not pay coupons under certain circumstances without triggering an event of default. Issuers also have the ability to call the bonds before maturity, which itself is typically 60 years or more and often perpetual. In some ways they are similar to tier 1 bank bonds. Like tier 1 debt, hybrid securities are deeply subordinated instruments and the extent of subordination is usually captured within the terms governing the particular security.

That said, there are differences between tier 1 and hybrid debt. For example, tier 1 debt mandatory triggers are tied to regulatory requirements and therefore have elements of standardisation, whilst corporate hybrids are more variable according to how much equity credit they are assigned by rating agencies. In addition, whilst banks require constant access to the market to finance themselves, corporate hybrids are often issued as one offs linked to individual events such as acquisitions or pension funding.

Why do corporations issue corporate hybrids in the first place? Corporate hybrids give issuers increased financing flexibility, for example with respect to interest payments and repayment maturity, whilst controlling overall cost of capital. Hybrids are sufficiently debt-like that a company’s interest payments to note holders are tax deductible. Additionally, hybrids are sufficiently equity-like that the company’s financial ratios are improved.

There are other reasons why it may be in a company’s interest to issue hybrid debt. For example, a company with pressure on its credit rating may issue hybrid debt as it is a way to obtain equity credit without issuing equity. In an acquisition scenario, the acquirer can use hybrids as a means of financing whilst reducing the impact on credit ratings. The benefit in this scenario is that by issuing hybrids the company can potentially avoid diluting existing shareholders through executing a rights issue.

From an investor’s perspective, hybrids potentially have a higher implied rate of return compared to typical corporate bonds, and offer risk diversification benefits. So these instruments can be an attractive proposition for investors and issuers alike.

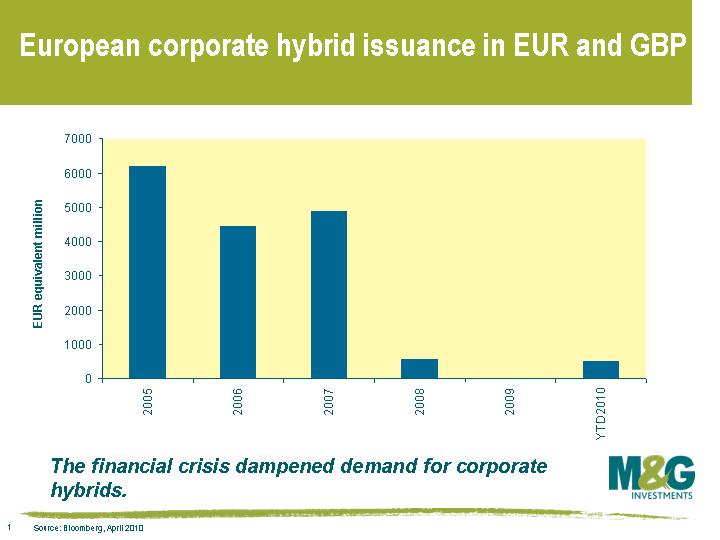

Despite their potential attractiveness, the hybrid market almost shut down as the financial crisis unfolded but is showing some signs of recovery. The current cohort of European hybrid issuers largely belongs to the 2005-7 vintages; these were all issued into a strong corporate bond market. 2008 and 2009 saw virtually no new hybrid issues as the financial crisis unfolded, but this did not spell an end to the instruments, as seen in this chart. Indeed the most recent issue was made by the Dutch grid operator TenneT in February 2010.

Despite their potential attractiveness, the hybrid market almost shut down as the financial crisis unfolded but is showing some signs of recovery. The current cohort of European hybrid issuers largely belongs to the 2005-7 vintages; these were all issued into a strong corporate bond market. 2008 and 2009 saw virtually no new hybrid issues as the financial crisis unfolded, but this did not spell an end to the instruments, as seen in this chart. Indeed the most recent issue was made by the Dutch grid operator TenneT in February 2010.

Given their complex nature it is important that investors understand the risks involved in investing in these types of securities by undertaking a thorough fundamental analysis of the company and the particular structural features of the hybrid security itself. For example, the replacement language, the call feature, the step-up rate, how the deferral trigger is defined and whether interest payments will be cumulative or not. Adding further difficulty to analysing these securities is the fact that the European market is very diverse; the rating agencies all use different methodologies, and the methodologies themselves are continuously evolving.

While the Greek god Perses (the god of destruction) is currently running amok in the Greek government bond market, we believe that the centaurs of the bond world, hybrid corporates, can potentially be a good source of alpha for bond investors providing they do their homework.

The past couple of days have seen Greek debt take a bit of a battering. Spreads on Greek government bonds are the widest they have been since the inception of the Euro, and Greek 5yr CDS is wider by 100bps+ versus the beginning of the week. This seems to have been driven initially by nervousness around the anticipated bailout, with rumours that the Greeks are trying to renegotiate the deal that was announced on 26th March. More seriously though, Greek banks, who ironically were the ones responsible for buying a lot of recent sovereign issuance, have now asked for Eur14bn in loan guarantees from the government, perhaps due to recent numbers that showed as EUR10bn drop in deposits (4.5% of Greek GDP!). This could be the start of a bank run.

Looking to the relatively recent past one will find that Argentina underwent something similar. They went through their debt fuelled crisis in the ‘90’s, with a bank run in 2001 as Argentines withdrew money from banks and converted into US dollars, culminating in sovereign default in late 2001.

The parallels between the two countries are quite striking. Argentina used to operate a currency peg to the US Dollar (abandoned in early 2002), effectively the same as having a common currency, in order to keep a lid on inflation. Argentina therefore imported US monetary policy, resulting in an artificially strong currency, and this resulted in artificially high imports (which meant a steady outflow of US dollars from the economy). The currency peg also gave the Argentinian public access to cheap US credit, which they were less than reluctant to use. Greece too has spent the past decade or so borrowing at artificially low rates of interest.

Corruption and tax evasion in both countries exacerbated their problems. Admittedly appointing political supporters to Argentina’s Supreme Court and an (alleged) illegal arms deals could be seen as more morally questionable than cooking the books, but where markets are concerned dishonesty on any level is a serious offence.

The levels of debt of the two however are not comparable. Unfortunately for Greece, they are starting from a considerably worse position than the Argentinians. In 2001 Argentina’s debt/GDP ratio and deficit as a percentage of GDP were 62% and 6.4% respectively. At the end of 2009, Greece’s debt to GDP was 114% and the deficit 12.7%

After the Argentinian crisis, the IMF, who repeatedly lent cash to Argentina in the 90’s, produced an evaluation report entitled The IMF and Argentina 1991-2001. It’s quite a hefty piece but on pages 6 and 7 there is a list of lessons learned and recommendations on how to avoid mistakes in the future. To me, the most interesting lessons are lesson 9 ‘Delaying the action required to resolve a crisis can significantly raise its eventual cost…..’ and recommendation 4 ‘The IMF should refrain from entering or maintaining a program relationship with a member country when there is no immediate balance of payments need and there are serious political obstacles to needed policy adjustment or structural reform’. Recommendation 4 must be a particular worry to the Greeks. This crises has been dragging on for a few months now without any decisive action having been taken and disagreements between Germany and the rest of the Eurozone over whether/how to lend a hand could be viewed as a ‘serious political obstacle’. Clearly the disagreement is what has caused the delay in a resolution but the longer the policy makers procrastinate the more expensive an eventual bailout will get.

When Argentina defaulted, the government offered a debt swap valuing existing bonds at only 35% of face value, the worst recovery rate in sovereign debt history. 76% accepted these terms, but the rest didn’t (and the holdouts are still fighting with the government today, which has locked Argentina out of international capital markets since it defaulted). With over half of outstanding Greek bonds still trading with a cash price in the 90s, if Greece does default (implied risk from CDS market is over 30% in the next five years) then investors potentially still stand to lose over half of their money.

A further worry is that when Argentina defaulted, the consensus (seemingly as now) seemed to be that there wouldn’t be contagion (see here). True, initial contagion at the end of 2001 was limited, but contagion increased through the second half of 2002. Only a $30bn IMF loan prevented a Brazilian default in 2002, and Uruguay experienced a banking crisis and defaulted in 2003. Argentina’s default resulted in borrowing costs increasing significantly in the region, and growth for all countries stagnated. What is particularly worrying is that, unlike with Greece now, Lat Am banks didn’t actually have that much exposure to their neighbour’s debt.

Democratic governments are designed and exist to promote and protect the interests of their population. Thus they tend to be described as “good”. Capitalists are seen to be out for themselves and therefore acting in their own selfish interests. They are often described as “bad”. However, in order to have a prosperous society one has to combine the socialism and fairness of democracy with the efficiency and ruthlessness of capitalism.

These two forces come together in the government bond market. On one side is the collective need to borrow to provide for your citizens needs (health, education, defence, etc) and on the other are capitalists who provide the finance for government spending. These capitalists can be described as either investors or speculators.

Investors are generally seen as good capitalists, while speculators are seen as bad capitalists. This line of thinking has once again come to prominence with the market’s attempts to value Greek debt, with holders of the debt who think it is undervalued described as benevolent investors, while economic agents who think the debt is overvalued (expressing their view through credit default swaps) described as devilish speculators.

European governments are now looking to see how they can regulate speculative investors who have used CDS to express a negative view on Greece’s ability to pay its debts. They argue that Greek government bondholders might actually want to see Greece default on its debt due to their holding of CDSs. It has been noted that CDS holders might be incentivised into pushing for Greece to enter default. Additionally – because the CDS market is over-the-counter – there is no way of finding out who the protection buyers and sellers are, adding to uncertainty and volatility in markets. The investment community counters these arguments by saying it should have the right through CDS to promote the efficient allocation of capital.

Putting the various arguments aside, let’s assume the governments win – after all, they regulate the market and can determine what contracts are legal. This banning of CDS would eliminate the tool of CDS for speculators to express a negative view, but would also eliminate the potential for speculators (investors) to express a positive view. If it is seen that the banning of negative CDS trades is a net positive for governments and society then governments could then move a step further and seek to ban the shorting of government bonds physically or through the use of the futures market. If that works then governments could progress to stop the shorting of national currencies as that position is the most aggressive step capitalists can take against a nation state. If that works then governments could stop criticism of their national finances. If that works… I think you know where we would end up!

This is the essential conflict between the state and the individual; are you an individual/speculator who is up to no good, or are you an individual/speculator who challenges the status quo for good? Should CDS on governments be transparent and not abused? Yes. Should it be banned? No. The CDS market should be a fair and level playing field. If governments think that CDS are mispriced then they should take the same response as they do in the FX market i.e. behave responsibly, influence the debate verbally, and then strongly intervene with the only medicine speculative capitalists respect, real money.

Today the date for the UK general election was announced. May the 6th it is. It is once again time for British citizens to place their X to choose the future direction of the country. From a UK bond investor’s perspective this could well be a significant catalyst in determining the future direction of UK economic policy too.

Although the latest polls are quite close, it seems likely we’ll get a new government. The question is what kind of government? And will the decision be made on the 6th May or will we be left with a hung parliament? A hung parliament is currently perceived to be a disaster – how can you have a catalyst for change when you have no one in charge?

The uncertainty of the result would be compounded by whether parliament is hanging to the left or to the right, and if you can excuse the horrendous image, how well hung parliament is! The fate of parliament would then be decided by the Liberal Democrats. What are they likely to do? They are likely to pursue the policies they believe in and to work with the mandated larger party, which due to the bipolar nature of the UK system could be either party, the one with the most seats, or the one with the most votes.

The critical thing about the UK election from a bond (and currency) investor’s perspective is the resolving of uncertainty over the future of economic policy. This is where the Liberal Democrats can increase or remove uncertainty and thereby extend or remove the UK risk premium based around the election. I think the latter alternative is the obvious political choice.

The reason they need to do that can be expressed in a less highbrow way. The biggest annual vote in the UK is probably the X factor. Imagine the final of X factor with three candidates on stage, the simply red Gordon Brown, the blue aficionado David Cameron, and the Bruce Springsteen inspired Nick Clegg who is in charge of their fates and appears to therefore be the Boss. Well, the one thing that Clegg can not do (despite being Born to Run?) is ask the electorate to vote again, because as the weakest link he would be eliminated if the electorate was forced to choose between the other two parties in traditional two party British political fashion, resulting in the Liberal Democrats losing seats and influence.

Therefore a hung parliament is not likely to lead to further indecision, and delaying of policy implementation, but like a clear victory, even a hung parliament should provide a catalyst for change, and a collapse in risk premiums that could benefit both Sterling and the Gilt market.

The granting of independence to the Bank of England following Labour’s victory in the 1997 UK General Election caused a collapse in inflation expectations. Whilst inflation expectations had been drifting down anyway, thanks mainly to globalisation and a demographic productivity boost, after independence was announced the 10 year breakeven inflation rate fell from 4% to 3.4% in just a couple of weeks. A year after independence, inflation expectations were down to 2.9%. With monetary policy out of the hands of politicians the long held view that the UK was a bit flakey on inflation faded away, and nominal bonds dramatically outperformed index-linked gilts.

Nowadays of course the UK has decent reserves of anti-inflation credibility (although funnily enough 30 year breakeven rates at 3.82% are nearly back at pre-independence levels), but we are definitely regarded as being a bit flakey on the fiscal side – just ask Bill Gross. At a gilt market lunch yesterday (hosted by BNP Paribas) former MPC member Tim Besley discussed his ideas for a fiscal policy committee (FPC) – “a politically neutral, expert body…that would assess the UK’s fiscal position”. As Besley’s blog states, other countries with similar fiscal councils “have reinforced government’s responsibility by raising the political costs of deviation”. After a post-election kitchen sink audit of the UK’s finances which finds that growth will be lower than forecast, off-balance sheet debt higher than declared and the cupboards bare, an incoming Conservative government can implement a VAT hike (which could take the annual RPI rate to 3.6% by the end of 2010) and buy fiscal credibility for the future by announcing the creation of a body like the FPC. Perhaps then we’d see a collapse in the UK’s CDS spread from its current level of 77 bps to something similar to France or Sweden (46 bps and 35 bps respectively)?