Guest contributor – Tamara Burnell (Head of Financial Institutions, M&G Credit Analysis team)

The publication of the Committee of European Banking Supervisors (CEBS) stress tests proved exactly the damp squib that most had been expecting. There was some additional useful disclosure on sovereign risk exposures (apart from a few German banks) but a decided lack of rigour in the regulatory approach. In total, only 7 “already failed” banks failed the tests. So all in all, the banking system passed the easy tests with flying colours, but at the same time is still on central bank life support and not strong enough to tolerate harsh regulatory proposals designed to prevent another crash. How does that work?

Indeed, since it was governments and regulators who were arguably being “tested” by the market, it is primarily the regulators who were the main “fail” candidates in this process. All they succeeded in doing was proving that the EU banking sector is too weak to be able to have a hope of meeting harsher Basel 3 capital and liquidity requirements by 2012. Stressing the banks to such a low hurdle (a 6% Tier 1 ratio after only relatively minor asset stresses) made it clear that regulators knew they were in no position to enforce Basel 3 on schedule. So it was unsurprising that the stress test results were followed almost immediately by an announcement from Basel that implementation of some of its key measures are being delayed until 2018, and that several measures were being significantly watered down. Indeed some cynics might argue that this was what CEBS had been trying to do all along, i.e. push Basel into changing its approach, to protect European narrow economic interests.

Banks (and regulators) seem to hope that by delaying regulatory reforms they will create positive sentiment around the banking sector. Indeed it has prompted something of a positive short term story in equity and credit markets, with banks seeing the opportunity to maintain their high leverage and asset liability mismatches for that much longer, and bearish investors have started to capitulate and accept that they can’t maintain an underweight position in banks until 2018. However, this positive momentum is unlikely to be sustainable – the problems faced (namely overleveraged banks, sovereigns and economies, all with a huge refinancing hurdle to overcome in the next 3 years) have not been tackled, and the issues facing bank creditors remain unresolved.

The key question now is whether the political and institutional will is still strong enough to demand radical changes to the way banks operate, and, in particular, to the way that bank creditors are treated in times of crisis. Although cosmetically Basel has made some concessions to ensure that changes to capital and liquidity requirements don’t precipitate the funding crisis they were designed to avert, behind the scenes some radical proposals are gathering steam. Regulators and politicians around the world continue to demand that next time around bondholders are the capital providers of last resort, rather than the taxpayer, and to this end regulators have been tasked with coming up with Resolution Regimes for global banks. As we see in corporate restructurings, debtholders usually have to recapitalise a company to maximise their recoveries – via a debt for equity swap or some sort of debt forgiveness – and a similar restructuring process is now being proposed for banks, so that existing creditors “bail-in” failed banks. This will require major legislative change and a change in mindset from market participants, so it can’t happen quickly.

Ultimately these changes will lead to bond investors being far more careful about which banks they lend to and at what price, which could force a painful contraction in bank balance sheets. But we continue to believe that in the long-term the costs of not reforming the banking system and perpetuating the “too big to fail” assumption would be far greater (another crash) than the benefit of the status quo (high leverage, large asset liability mismatches, poor liquidity, high returns). So we still believe that important, painful and far-reaching reforms will be made, even if the global economy and banking system are not robust enough to tolerate these changes now.

Regulators are faced with only tough choices. Do they force through the big bang changes now, with the possibility that we re-enter a full-blown bank funding crisis? Or do they give the banks and their creditors more time to adjust to the coming changes? The latter would be done in the hope that by the next time we have a banking crisis we will have a system whereby even senior unsecured bank creditors could see principal write down or debt-for-equity swap features that help to recapitalise failing bank institutions when it is most needed (unlike the recent crash when there was no such support provided by debt-holders of banks).

The banking regulatory and investment landscape is changing. And it is changing for the better: another crash will be less likely and the costs will be borne to a greater extent by all stakeholders, rather than just shareholders and taxpayers. It is just not changing quite yet.

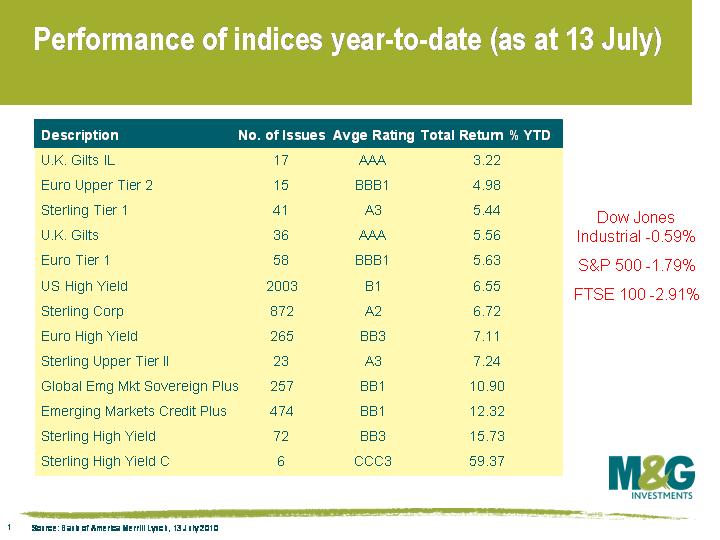

We have now passed the halfway mark of 2010 and we thought it would be interesting to put together some figures to show how various bond indices have performed year-to-date (as at July 13). BofA Merrill Lynch provide an excellent download service via Bloomberg which has allowed us to extract the data in the following table. Interestingly, in this perceived world of risk on/risk off, performance YTD in fixed interest markets has not necessarily reflected the amount of credit risk an investor is willing to take.

Within bond markets, AAA rated index-linked gilts have provided a total return of just over 3%. UK gilts have given investors a solid 5.5% return, outperforming some of the higher risk indices like sterling tier 1 and Euro upper tier 2 debt. The financial indices suffered as risk aversion increased due to concerns about the banks exposure to peripheral sovereign debt. The star performers YTD are the corporate indices, particularly high yield, which in Europe and the UK has returned 7.11% and 15.73% respectively. The Sterling High Yield C index (which is actually CCC & below) has returned a massive 59.37% YTD – though this reflects the fact that the index consists of only 6 issues so big moves in a constituent of that index can swing the returns. Emerging market sovereign debt and emerging market credit have provided investors with double-digit returns, a reflection of the solid macroeconomic conditions that many emerging market nations are currently enjoying. Note that all returns are measured in local currency terms.

We have also included some of the major equity indices in the table, confirming the choice that Paul the Octopus made last Friday.

Some Friday afternoon fun for our readers on a day when the US 2 year Treasury Bond just hit an all time low of 0.5765%…

Guest contributor – Tamara Burnell (Head of Financial Institutions, M&G Credit Analysis team)

Press reports following the meeting of EU finance ministers yesterday suggest that the eagerly anticipated Committee of European Banking Supervisors (CEBS) bank stress tests will be extremely “unstressful”. There’s talk of government bond holdings only being stressed for “market price volatility” if held in the trading books (implying bonds held to maturity will not be stressed), pass thresholds for capital ratios being set at very low levels, and results for multinational groups only published on a consolidated basis initially, giving creditors no insight into the quality of their actual legal entity counterparty. Indeed, comments reported on Bloomberg from the Greek Finance Minister that Greek banks are all expected to pass the stress tests, and from the Irish Finance Minister that AIB and Bank of Ireland should have few problems passing the stress test, highlight how pointless the whole exercise is looking, given those two countries’ banks have very clear and obvious problems.

Without any firm detail of exactly what the stress tests will involve, other than the most recent CEBS press release, it is hard to provide a detailed critique, but one particular concern we have is the absurdity of the Spanish regulators testing the Caja sector on the basis of consolidated legal structures that don’t yet exist and where capital is not going to be fully interchangeable within the groups. Indeed it is hard to see how anyone can be relaxed about the condition of the Spanish banking system when Bank of Spain data shows that Spanish banks increased their borrowings from the ECB by 48%, to €126.3bn during June. Similarly, we’re confused by some of the names that aren’t on the stress test list, with the Credit Mutuel Group in France, Nationwide in the UK, and Banca Popolare de Milano not making the list, perhaps because all have complex ownership structures which would make raising fresh capital extremely difficult. German Landesbanks claiming to be “very relaxed about the stress” is particularly worrying, given the track record of Landesbanks having to admit to chunky losses on virtually every problem asset class. And what wholesale markets really need is some reassurance on the financial strength of the actual counterparties active in wholesale markets, particularly that of the investment bank subsidiaries of both EU and non-EU banking groups, which will not be provided by the stress tests as far as we are aware.

However, most ridiculous of all is that the banks are simultaneously claiming that they are so strong that they will easily pass all possible stress testing scenarios, and yet so weak that they cannot cope with Basel 3 implementation by 2012 or the withdrawal of central bank liquidity facilities. How can the banks claim they are too strong to be concerned about the stress tests, but are too weak to implement painful and much-needed regulatory reforms? Any “clean bill of health” given to the banks in the stress testing exercise will therefore have to be accompanied by a commitment to enforce planned regulatory changes swiftly and comprehensively, if it is to carry any credibility whatsoever.

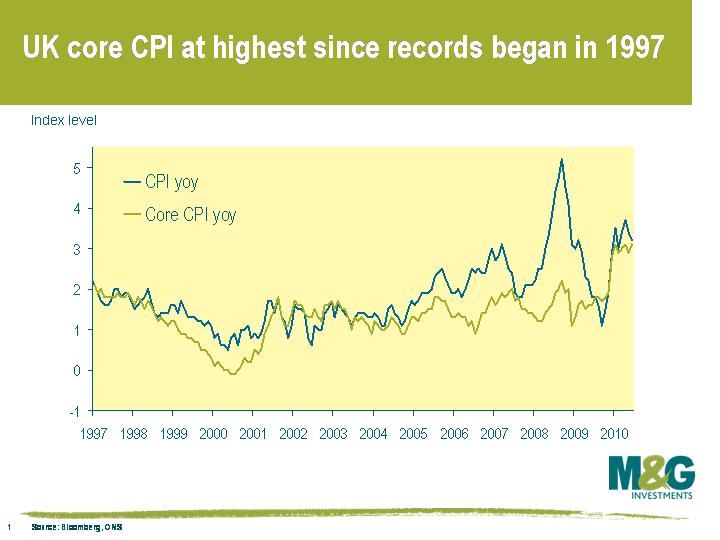

The good news was that UK CPI fell from 3.2% to 3.1%. The less good news was that this was 0.1% higher than expectations and remains above the 3.0% upper bound (inflation hasn’t been below 3% since December last year). The worrying news was that the Core CPI measure, which excludes food, alcohol, tobacco and energy prices, jumped 0.2% to 3.1%, and was 0.3% above expectations. Core inflation strips out the more volatile elements of inflation, and if you believe these elements are temporary in nature, then it provides a ‘truer’ picture of inflation. This is the highest core inflation rate since records began in 1997, although it’s a rate that’s been equalled twice already this year. This chart shows CPI versus core CPI since 1997.

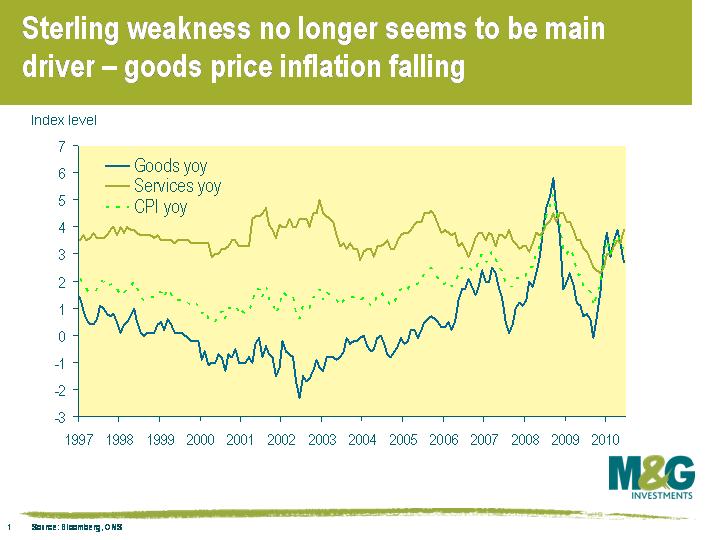

The reason for inflation coming in higher than expected was down to the services component (see chart), which is also a bit worrying. Goods price inflation (currently 55% of the CPI bucket) had been the main driver of the UK inflation rate, with part of the reason likely to have been the lagged effect of sterling weakness (see previous blog here). However, an increase in the services component (45% of CPI) suggests that inflationary pressure is beginning to come from domestic sources rather than international sources.

This does seem to lend some support to the MPC’s chief hawk Andrew Sentance, who has today again argued that spare capacity in the economy is not as large as was previously supposed. As explained from page 9 of his speech today, unemployment is lower than has been seen at this stage of previous cycles (and labour demand may be picking up), companies have adjusted quickly to lower levels of demand and are not reporting significant spare capacity, and wage growth has exceeded expectations. “As spare capacity has not exerted much downward pressure on inflation so far, so there must be a high degree of uncertainty about its future impact”.

Does this mean that we can look forward to a series of interest rate rises soon? Unlikely. Andrew Sentance was the only member to vote for a rate hike in June, and in today’s speech, even he concluded that he is not in favour of a sharp rise in interest rates, favouring “a gradual rise in the Bank Rate which would be aimed to avoid destabilising confidence through a sudden policy lurch”. The majority of MPC members also need to agree with Sentance, which may be tricky if the rumours that Mervyn King believes that the ‘Bank rate will stay low for four years‘ are true. Furthermore, we have little idea yet how the UK or global economy will react to the huge fiscal tightening that is coming, which leads me to believe that even if inflation does rise further through the remainder of this year, UK interest rates are unlikely to rise until economic growth follows a similar trajectory.

In the recent emergency UK budget it was announced that public sector indexation would change from RPI to CPI from April 2011. Now, the government is proposing moving private sector schemes and the Pension Protection Fund (PPF) indexation to CPI too. As Pensions Minister Steve Webb argued, it makes sense switching to CPI as it’s the measure that the BoE targets and (slightly more dubiously) CPI is a more appropriate measure of pension recipients’ inflation experiences.

RPI has historically been higher than CPI, exceeding CPI by 0.55% on average over the last twenty years, so if the differential between the measures continues in future then this proposed change would reduce pension fund deficits but would penalise scheme members if (and presumably when) it is implemented.

The problem with this proposal is that you can’t buy CPI linked assets in the UK – they don’t exist. While the correlation between RPI and CPI is reasonably close as you’d expect, the difference was as high as 3.1% in 1989 and is currently a relatively large 1.7%. RPI linked assets are still a better hedge against inflation than any other asset class, but there will definitely need to be CPI linked assets at some stage.

It may be possible to restructure the existing RPI linked index-linked gilts, but the easiest thing would be to issue new CPI linked index-linked gilts. This would make the RPI linked assets currently in existence pretty redundant. The good news is that this change, assuming it happens, will likely take years rather than months to implement and even then could well be gradual. Furthermore, in the meantime investors have no choice other than to continue buying RPI linked assets to hedge against inflation.

But it’s clearly a negative for inflation linked gilts overall, and we’re seeing that in terms of price action today. Longer dated index-linked gilts are getting hit hardest, partly because they’re longer duration so are more sensitive to changes in yields, and partly because the biggest buyers of long linkers are the pension funds. At the time of writing, UKTI 1.125% 2037s are down over 2% so far today, while the UKTI 0.5% 2050s are down 3.5%.

Linkers maturing in 20 years or longer have now been in a bear market year to date, which is quite incredible given that long dated conventional gilts (ie those maturing in 15 years or longer) have returned over 13% over the period. The significant underperformance of linkers has come about despite the UK inflation rate rising significantly this year, with the year on year rate of CPI climbing from 2.9% in December to 3.4% in May – as mentioned in October here, changes in the real yield is a much more important driver of returns for longer dated index-linked gilts than changes in short term inflation.