Imagine if you had nine of the most skilled doctors in the country examining a patient, and you had such a range of views that one doctor demanded emergency surgery and an immediate series of organ transplants, and at the other end another doctor insisted that the patient is in such robust health that he must be discharged immediately and return his wheelchair and medicines on the way out. You might not have much faith in the skill of those doctors. Now I’m sure there are disagreements in the medical profession about the best course of treatment for illnesses, but when it comes to economics it’s the norm, rather than the exception. In the UK’s Monetary Policy Committee you have Posen at one extreme, asking for more emergency QE, and at the other end Sentance, wanting rate hikes. Isn’t it incredible that the science of economics (the dismal science) is so, well, useless?

At the same time as we don’t know whether to print money or restrict it, we have no real understanding of whether fiscal stimulus in the face of weak demand is the priority, or whether it is more important to get public and private debt burdens down. If you read Paul Krugman’s excellent blog you’d believe that another massive stimulus package is imperative. Yet George Osborne and many on the right think that austerity is the answer to getting the western economies back to growth in the medium term. Why don’t we know? I think it’s important to acknowledge how limited the data set that economists have to work with actually is. “Modern” capitalism is barely a couple of hundred years old, and a truly globalised free trade economy perhaps less than two decades old. Our data set for QE pretty much only includes Weimar Germany, Japan and Zimbabwe; our understanding of the creation of massive currency unions is almost entirely theoretical; there’s only been one Great Depression – one data point on which to base our models and respond to our current predicament. Let’s be frank and upfront – economics is about forecasting the behaviour of irrational crowds in situations we’ve rarely, or never seen before (yet many neo-classical economic models make rationality a key assumption!). We’re bound to get it wrong.

So for what it’s worth – and given the grief I got for posting the Tea Party’s right wing views on Quantitative Easing earlier this year, here’s the left leaning False Economy website, which argues that government spending cuts are the wrong thing for the UK’s current predicament. In particular this video by Professor Mark Blyth of Brown University is worth a watch – I hadn’t heard of the concept of the Fallacy of Composition before. What might be right and appropriate for an individual economic agent might be terribly wrong for the collection of economic agents. For example it might be right for the UK to try to reduce its debt, but to do so at the same time as every nation is doing so could be disastrous.

And whilst we are on the subject of the left wing – why on earth doesn’t the US have one? It is staggering that the bottom 40% of workers in the US economy have not had a real wage increase since – wait for it – 1979. Yet real US GDP is up by over 125% over that period, and the profits share of GDP is exceptionally high by historical standards. The controlling power of the myth of the American Dream is amazing.

So that’s it for 2010. My guess is that 2011 will see more of the same, with sovereign issues continuing to dominate the headlines (and Spain’s huge Q1/Q2 debt refinancing needs will be the next big test for the Eurozone). We’ll post our thoughts on these and other issues of the day on this website (like – will the loss of output caused by the UK’s Royal Wedding send the economy back into recession?). We might even make it our New Year’s Resolution to learn how to Twitter (tweet?). Happy New Year.

The convention in the market is to estimate a country’s degree of distress by looking at the yield spread over a ‘risk free’ rate. So in the case of eurozone countries, people tend to look at the spread over German government bonds.

While this spread is clearly important, it’s more relevant to look at the absolute yield level if you’re trying to figure out whether a country’s debt is sustainable. After all, if German government bonds yield 1% and the spread is 3%, the country can borrow at 4%. But if German government bonds yield 4% and the spread is 3%, then borrowing costs are 7%. That’s a whole new ball game.

The problem that the Eurozone faces right now is that not only have peripheral spreads been rising, but the risk free rate has increased too. German 10 year government bond yields have jumped from 2.1% at the end of August to 3% now, which is probably due to a combination of stronger European economic data, a sell off in US Treasuries, and the potential for a peripheral bailout to be very expensive for core Europe (Germany and France are hardly debt free, with public debt/GDP ratios likely to exceed 75% in Germany and approach 90% in France next year even in the absence of bailouts).

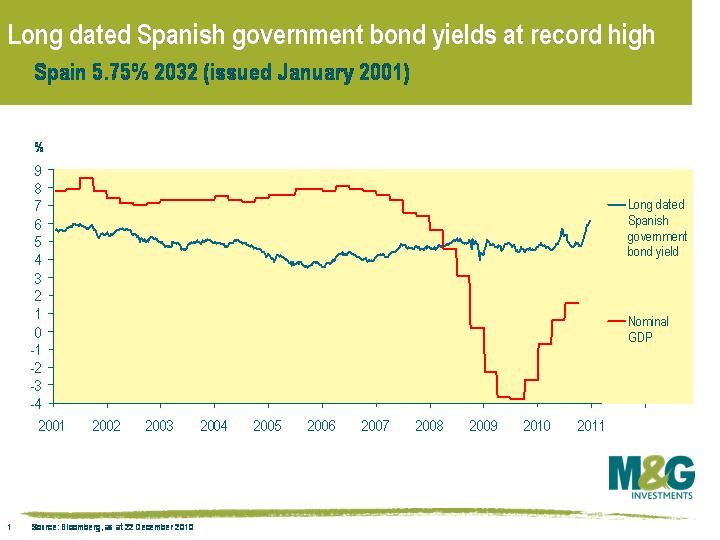

Long dated Spanish government bond yields are now at the highest for a decade, and this is a major problem if you consider the mathematics of government debt ratios. A country’s government debt/GDP ratio is a function of three things; the change in a country’s fiscal balance as a % of GDP, the difference between debt interest costs and nominal growth as a % of GDP, and changes in the stockflow adjustment (which tends to be relatively small). So assuming that a country runs a balanced budget and the stockflow adjustment is zero, if a country’s interest costs on its debt exceed its nominal GDP growth then its debt/GDP ratio will steadily creep up.

The average interest cost on all outstanding Spanish debt is currently just under 4%, which isn’t too alarming. The problem is that long dated Spanish government bonds now yield over 6%. As the chart shows, a 6% interest rate on long term debt was fine a decade ago, when nominal Spanish GDP was running at 7-8% per annum. But Spain’s interest costs will steadily climb higher as it comes to the market to borrow more money and roll over its existing debt. Any increase in interest rates from the ECB will accelerate the increase in interest costs and put even more pressure on the weaker Eurozone countries since short term borrowing costs will jump in tandem (five year Spanish government bonds already yield more than 4%). Spain needs to offset this steady rise in debt service costs with a budget surplus, which is not likely for the foreseeable future, or hope that its nominal growth rate jumps back above its borrowing costs, which is also not likely for the foreseeable future. Long term borrowing costs of 6% are not sustainable.

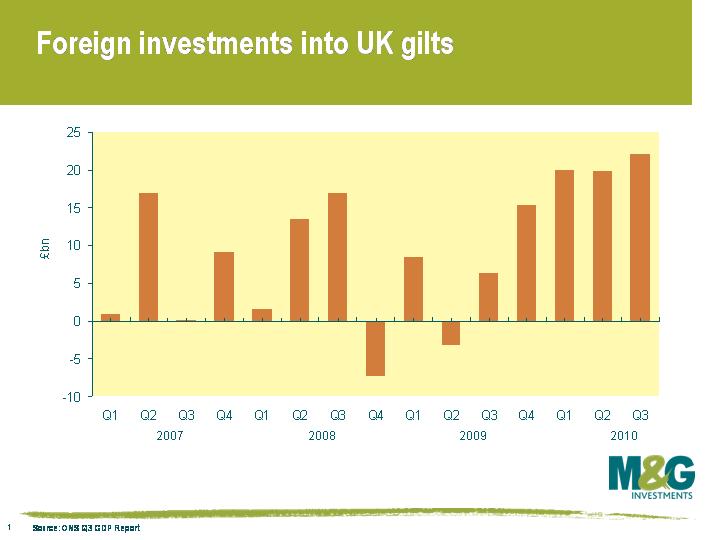

After December’s big sell-off in US Treasuries on the back of fears about the US’s creditworthiness, and the surprise at yesterday’s record monthly budget deficit in the UK, there’s been a lot of talk about a bond market “buyers’ strike”. In particular the western bond markets’ reliance on Asian central banks has made many nervous that a change in risk appetite there could result in strings of uncovered bond auctions and significantly higher yields as borrowing costs rise.

Perhaps this is overly pessimistic. Although this data is for Q3, and therefore doesn’t reflect the most recent wobble in confidence, it shows that foreign investors bought £22.115 billion of UK gilts in that quarter – and £77 billion over a 12 month period, a massive help for the UK’s financing requirements. This shows that overseas investors are confident that the UK will remain a AAA rated bond market (with the debt burden tackled by the Tory/LibDem austerity programme), and also reflects a safe haven status at a time when peripheral European bond markets have been collapsing. So no need for panic in the UK gilt market yet – but if yesterday’s numbers reflected the start of a string of poor budget deficit numbers, and inflation remains higher than most gilt yields (you don’t earn CPI until you lend out to 8 years on the yield curve, and you don’t earn RPI anywhere outside of inflation-linked gilts) then there will be cause to worry.

Here’s the link to the statistics – the gilt numbers are on page 100, column F.3321.

Thanks again for another bumper crop of entries for the quiz. The answers are below, and the winners are:

First Prize (Amazon voucher for £103.20): Cecilia Liao from C. Hoare & Co

Second Prize (The Big Short by Michael Lewis): Marton Hübler from Fidelity Investments

Third Prize (as above): Nick Tudball from BNP Paribas

M&G staff member prize: Luke Coha

1. Who overcomes his fear of flying and a drinking problem to win the love of an air stewardess on a flight from LA to Chicago?

Ted Striker in the film Airplane!

2. Who is the world’s largest private sector employer?

Wal-Mart with 1.8 million employees.

3. Which Three Letter Acronym (TLA) links Scottish ski lifts, Innocent Smoothies and Pringles?

VAT. The Scottish ski lift operators want to be classified as public transport rather than private vehicles, Innocent Smoothies claim to be “liquified fruit salads” rather than drinks, and Pringles claim to be biscuits not crisps, all to exempt them from VAT.

4. Which Scandinavian Billy has sold over 40 million units?

The Ikea shelving unit.

5. What was recorded in Lagos, won a Grammy and has a front cover that pictures Michael Parkinson dressed as a convict?

Band on the Run by Wings.

6. Please identify A, B, C and D

A = Spain, B = Greece, C = Portugal, D = Ireland, X = Poland, Y = Hungary

“A is not B” – Elena Salgado, A Finance minister, Feb 2010.

“C is not B” – the Economist, 22nd April 2010.

“D is not in B Territory” – D Finance Minister Brian Lenihan, November 2010.

“B is not D” – George Papaconstantinou, B Finance minister, 8th November 2010.

“A is neither D nor C” – Elena Salgado, A Finance minister, 16 November 2010.

“Neither A nor C is D” – Angel Gurria, Secretary-general OECD, 18th Nov 2010.

Bonus point, identify X and Y

“X is not Y” – Jan Winiecki X MPC member

7. Which word comes from the name of a cattle rancher who went against convention and didn’t brand his cows?

Maverick after Samuel Maverick.

8. What is this?

It’s the memorial at the site of the Hindenburg airship disaster in New Jersey.

9. What did you have to do to get into Morrissey’s first ever solo gig, back in 1988?

It was a free concert at Wolverhampton Civic Hall, and you got in if you wore a Smiths or Morrissey T-Shirt.

10. Why would it be wrong to call her Stacey, Jane or quiet girl?

Because that’s not her name (from the Ting Tings song).

11. What is the Chinese credit rating agency called, and what is its rating for the United States?

Dagong Global Credit Rating Co. cut its rating for the US from AA to A+ in November this year.

12. What is the Chinese name for this popular Dim Sum dish?

Char siu baau.

13. What do Vince Hilaire, Andre Previn (and the LSO), and Desmond Tutu have in common?

They all feature in the lyrics of the Beloved song “Hello”.

14. Who, collectively, are these guys?

They are The Octonauts (Kwazii Kitten, Captain Barnacles Bear and Peso Penguin).

15 . “Ireland stands as a shining example of the art of the possible in long-term economic policymaking, and that is why I am in Dublin: to listen and to learn.” Who said that in February 2006?

16. “Who is Jxxx Gxxx?” – the opening line of an old book that is influential once again. Fill in the blanks.

John Galt. This is the opening line of Atlas Shrugged by Ayn Rand.

17. What will Marcus Trescothick get £1,000,000 for if he does it next year?

Hitting a ball over the pavilion at Lord’s cricket ground.

18. Which now famous graffiti artist originally worked using the tag “SAMO”?

19. What was this dog called?

Laika – the Russian dog that went into space in 1957.

20. Complete the joke: “I’ve just bought a new aftershave that smells of breadcrumbs…”

The birds love it.

Thank you again for all of your entries, and for making the Bond Vigilantes website the UK’s 2,040,128th most viewed. Happy Christmas and have a great 2011. Normal doom and gloom bond market commentary will resume next week.

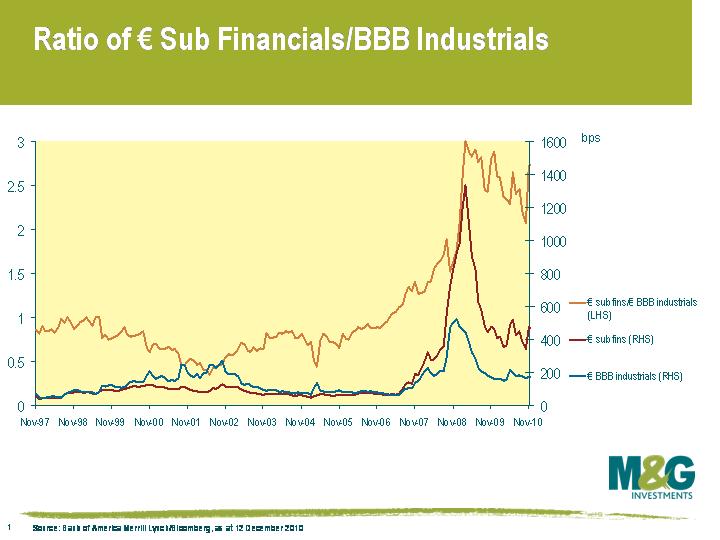

A renewed focus on European bank balance sheets, their sovereign exposures, fears of creditor bail ins and a general risk apathy saw subordinated financials spreads move significantly wider through November. I’ve charted the ratio of spreads, comparing the Merrill Lynch EMU Financial Corporate Index, Sub Type (EBSU) against the EMU Corporates, Industrial, BBB rated (EJ40) below. Whilst sub financial spreads are still somewhat tighter than levels reached in June 2010 ( +466 vs +519), the relationship between financials and non-financials has moved back to levels not witnessed since the end of 2009.

Where does this relationship go from here? Is a ratio near record wides sufficient to entice investors back into subordinated financials ?

There were echoes of August 2008 for a few hours last week. The yield spread on 10 year Spanish, Belgian and Italian government bonds over German government bonds spiked to a euro era record, while the cost of insuring Portuguese and Irish government bonds against default also hit a record high. Greece has already become a zombie sovereign, and is being kept alive with a cash drip from the EU and IMF. The Irish have been forced to bring out the begging bowl after markets decided its banks’ debts were too big for the sovereign to stand behind. Portugal is wobbling. It’s debatable whether a collapse in these countries is systemic (I believe it probably is) but there is little doubt that if Spain ends up in a position where it requires a bailout, then things could get very, very nasty for financial markets. Spain’s economy is more than twice the size of Ireland, Greece and Portugal combined. And if the evidence of the past few weeks is anything to go by, then Italy et al would be in the queue right behind Spain. The prospect of Europe needing a bailout en masse doesn’t bear thinking about, which unfortunately seems to be the approach that the authorities are taking at the moment.

What are the solutions to this unfolding disaster? Many have argued that the problem lies with the single currency, which I agree with – the UK had a severe banking crisis, yet thanks largely to sterling depreciating almost 15% on a real trade weighted basis since the end of June 2007, the UK had a nominal growth rate of 5.9% in Q3 this year. The Euro has depreciated by only 5% over the same period, which has been insufficient for the weaker Eurozone countries. Some have argued, therefore, that the solution is the breaking up of the Euro, which I disagree with. If the non-core countries attempted to leave the euro, it would likely result in a collapse of the banking sector within those countries as depositors flee to stronger currencies. Some have argued Germany could leave the euro, which would result in a much more competitive euro. However, I suspect that this would bring about the collapse in the German banking sector, since the banks’ liabilities (customer deposits) would be in the new strong Deutschemark, while a significant chunk of German banks’ assets (which includes peripheral sovereign debt) would be in the weaker euro.

The temporary solution that the ECB has engaged in has been half-hearted buying of Irish, Portuguese and Greek government debt. When the policy is implemented with force, as was the case in May when the ECB purchased over €30bn of sovereign debt, the policy can be effective. The stepping up of peripheral sovereign purchases has also helped the markets rally in the past few days. But the main problem with such a policy is that it introduces huge moral hazard – why should Spain engage in painful austerity if it knows full well that the ECB will always be buyer of last resort and it will never face a funding crisis? This seems to be the German fear – indeed just this morning, Juergen Stark was quoted saying that states are responsible for their own debts and the ECB’s job is not to finance EU member states. This approach makes the likelihood of fiscal union and a single European debt agency exceptionally unlikely. Similarly, increasing the size of the stability fund is unlikely to prove popular with core countries given that if this sovereign debt crisis turns out to be anything other than a liquidity crisis, then it’s going to be paid for by taxpayers in the core countries. (We’ve also got concerns about the stability fund’s viability anyway – more on this in the next link.) I can’t see any solution other than debt restructuring for banks and very likely a number of sovereigns in the long term, and that’s not going to be pain free to put it mildly.

So it’s with these gloomy thoughts in my head that I recorded a short video a week and a half ago, discussing the problems facing the peripheral sovereigns in Europe over the short to medium term (you’ll notice my arm’s in a sling, let’s just say it was a sporting injury). Some details are no longer bang up to date, such as Ireland has since been given longer to repay its borrowings, but you’ll get the gist. And I haven’t even gone into one of one the biggest long term problems facing Europe’s solvency – demographics (see a blog I wrote on this subject last year here). As Europe sang, “will things ever be the same again? It’s the final countdown”…..