From previous blogs (see here and here) you can see that we are not a big supporter of the single currency from an economic point of view. However we recognise the authorities’ political and economic desires to maintain it despite its economic inefficiencies. This does not stop us thinking about policymaker options. If the single currency is to be unwound what is the least damaging way to do it?

We have spoken before about the concept of the neuro being a successor currency to the euro. This is required to ensure a more orderly market can continue in financial and commercial contracts drawn up in euros, and to more fairly balance the outcome of the euro’s demise between savers and borrowers.

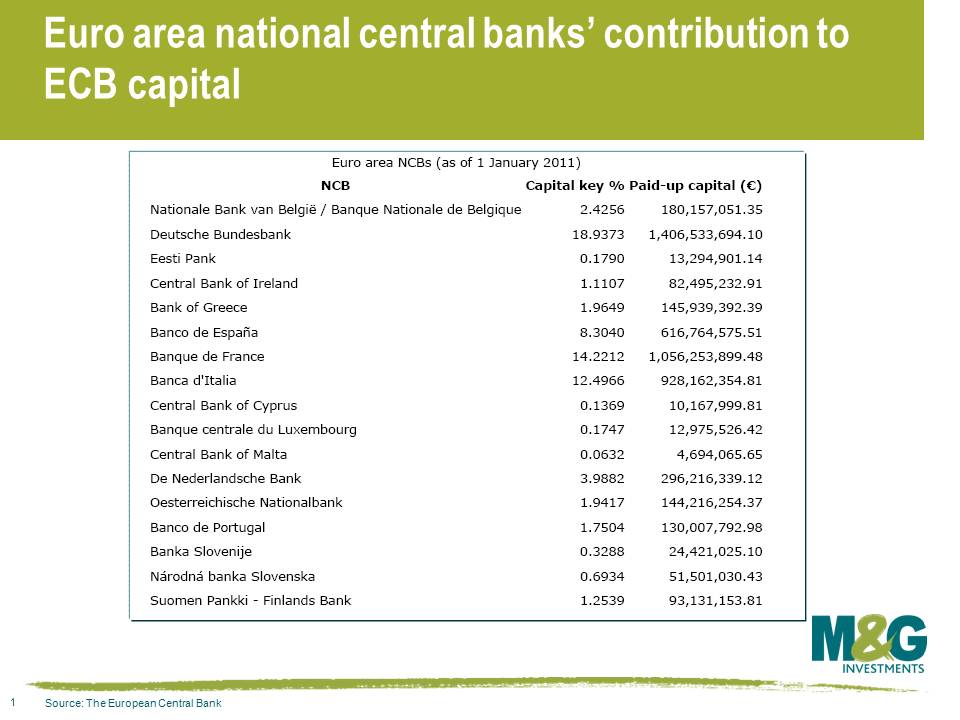

This neuro basket of currencies would succeed the euro in much the same way as the euro succeeded the ECU. The basket of currencies forming the neuro could be based on euro area nations’ contribution to ECB capital as per the table below.

The single currency vision is under huge stress, signalled by German board members defecting from the ECB, outside central bank governors like Mervyn King talking about unmentionable unmentionables, and comments from outside government officials like Geithner, and yesterday William Hague who said the euro is ‘a burning building with no exits’.

The authorities need to examine a plan b to at least mitigate the disaster that a disorderly introduction of national currencies would bring. The existence of the neuro as an alternative plan b, even if never enforced, would provide less downside than current thinking and so help market stability.

We’ve had numerous concerns with EFSF ever since it was announced last year. Here’s our top 10, in no particular order;

(1) The considerable risk of one or more of the AAA rated guarantors being downgraded, which would threaten EFSF’s AAA rating.

(2) The fact that the EFSF’s current size and form aren’t sufficient to bail out Spain and Italy.

(3) A larger EFSF, which solves point (2), could weigh on sovereign ratings and result in problem (1).

(4) Legal risk. Investors in EFSF bonds have no understanding of what the money is to be used for (initially investors were told the facility was not to be used for bank bailouts but that looks likely to change). And if an EFSF guarantor reneges on its guarantee then there’s no payback (so if Slovakia pulls out, Germany just ends up guaranteeing more).

(5) Some of the initial guarantors (Spain and Italy) are themselves in trouble and probably need bailing out. If problem (3) is somehow overcome, then that means more EFSF bonds. But then you run into the problem of fungibility. Each EFSF bond has different guarantors, so the first EFSF bond was issued in January to bail out Ireland. Portugal remains to this day one of the guarantors for that particular bond, despite Portugal itself also needing to be bailed out (the two subsequent EFSF issues were to bail out Portugal, of which obviously neither Portugal nor Ireland are guarantors)

(6) The existence of yet another large AAA rated supranational entity will presumably crowd out private sector issuers, governments and particularly other supranational or agency entities, pushing up borrowing costs. Linked to this, the existence of yet another AAA rated supranational entity will get investors wondering about the strength of the sovereign support for those EU financing structures that (unlike EFSF) don’t have an ‘explicit’ guarantee.

(7) Further down the road, if bank or sovereign restructuring is necessary and the EFSF guarantors need to pay out to the EFSF investors, then the guarantors will need to raise money by issuing bonds, which increases debt levels, which leads you back to point (1).

(8) A sovereign restructuring would be proof that the EFSF support mechanism and fiscal discipline measures have failed. This wouldn’t be a surprise – EFSF doesn’t reduce debt burdens or encourage debt sustainability. It does nothing to address solvency.

(9) There’s been enough trouble designing the EFSF, but it is only supposed to last until 2013, at which point we start all over again with the European Stability Mechanism (ESM). And the ESM potentially subordinates the EFSF, taking seniority over existing creditors.

(10) EFSF is not prefunded. Investors need to be persuaded to part with billions of euros to invest in a vehicle with an ever-expanding mandate that lends money to European governments and banks at precisely the time when the market has decided that those governments and banks are insolvent.

Let’s focus on the last point. So far only €13bn of EFSF bonds have been issued; two five year bonds and one ten year bond. It looks like the intention is for many, many billions more to be issued. So the supply of EFSF bonds sharply increases, and at the same time, investor demand will likely fall as investors become increasingly uncomfortable about lending to the EFSF for all the reasons listed above. Supply up, demand down, not a good combination.

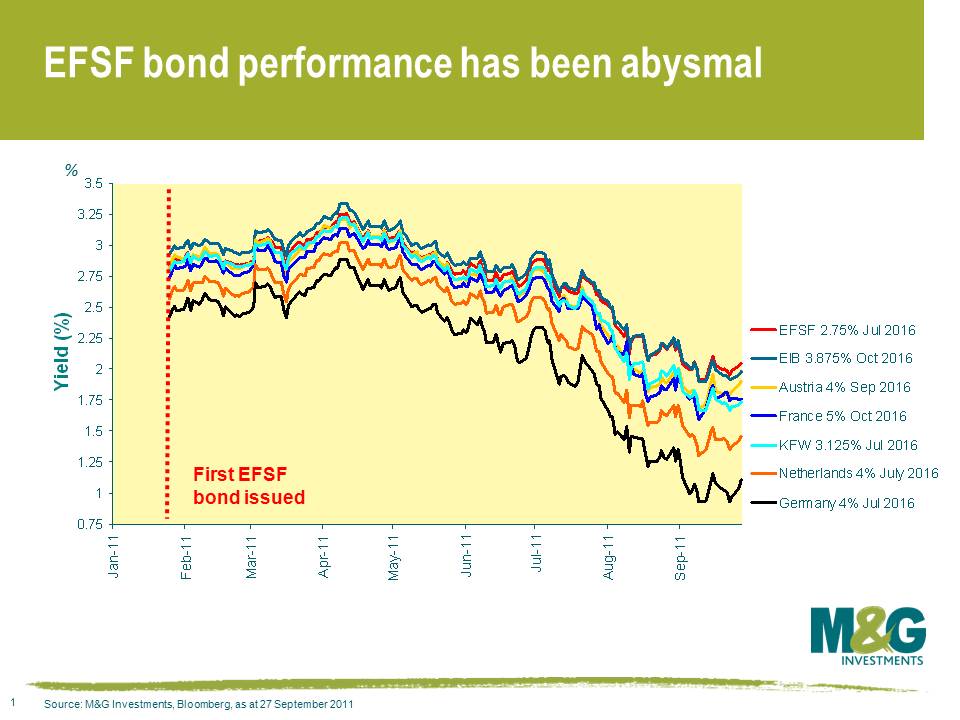

The chart below shows that the market is already losing confidence. Despite being ‘guaranteed’ and priced to perform when issued (and hence massively oversubscribed), the first EFSF bonds that came to the market in January now yield 100 basis points more than German government bonds. Curiously they also now yield more than European Investment Bank (EIB) bonds, where EIB debt only has an implicit guarantee from member states. A continuation of this trend will likely result in the ECB being the only end buyer of EFSF, which is something that the Northern Europeans are desperate to avoid.

It’s been two and half years since our last visit to New York. As you can see in this latest video, the past few tumultuous years in the markets have not been kind to Jim, Richard and Stefan. Earlier this week they visited New York, meeting with a number of economists and strategists, where talk was dominated by developments in Europe. In this latest video update, you can hear the Team’s views on the outlook for the US economy, the Fed’s latest policy moves and valuations in corporate bond markets.

When it was all academic, I enjoyed reading about the causes of the Wall Street Crash, the Great Depression and the German hyper-inflation. Policy errors abounded. The UK going back on to the Gold Standard in the middle of the crisis and sending the economy down in to a deflationary spiral. Andrew Mellon, US Treasury Secretary, saying “liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate farmers, liquidate real estate…it will purge the rottenness out of the system” (and letting the banks go bust). France demanding punitive war reparations from a desperately weak Germany, causing money printing and social unrest.

So if what we’re seeing right now is the start of a second wave of the Great Recession, what will historians think were the big policy mistakes in the couple of years since the first down-wave ended in 2009? Here are a few ideas – the 10 recent policy errors that have sent us back to the brink:

1. The ECB hiking interest rates twice this year in response to a commodity led inflation overshoot. Whilst I guess this gets reversed next month (or even sooner?) and the ECB cuts, the damage this did to confidence and to European funding costs was significant, not least because it caused the Euro to remain relatively strong. There was no evidence of second round inflationary effects, and the hikes came at a terrible time in the recovery.

2. The Tea Party and the idiots on both sides of politics in the US not coming up with even small compromises that would have given S&P an excuse not to downgrade the US from AAA.

3. The continuing Osborne UK austerity programme. As economic growth deteriorated, as youth unemployment rocketed and as confidence collapsed, he announced there was no Plan B. “Liquidate, liquidate, liquidate”, as Mr Mellon might have said, applauding.

4. Not banning shorting via sovereign CDS. We like CDS, we use CDS. But if they didn’t exist, the ECB could have aggressively bought peripheral European bonds and driven their yields down. Nowadays, whilst they were doing this in the physical bond market, the market was signalling its disbelief via wider CDS spreads. This visible secondary market doesn’t allow anyone to suspend disbelief. The price action in sovereign CDS dominates sentiment – just take a look on Twitter.

5. Over-regulation of the banking sector. I’m not sure about this one, because the banks are evil, right? But the backdrop of Dodd-Frank in the US, the global solvency regulations and Basel 3, the ring fencing of retail/investment banking etc. doesn’t provide an environment in which bank lending will aggressively recover. That’s if you think more bank lending/leverage in the system is a solution to this mess.

6. Not bailing out Greece/not letting Greece go bust quickly. It kind of didn’t matter which, but one of them could have saved the Eurozone. Greece started to wobble at the end of 2009, so we’ve had nearly 2 years of sovereign debt uncertainty now. Incidentally, could you compare the clamour for austerity for the Greeks now, to the French demands for implausible payments from Germany after the first world war?

7. Doing the wrong kind of Quantitative Easing. Operation Twist? The Fed needed to inject printed money directly into a broken housing market and underwater mortgages, boosting labour mobility and getting cash to those with a high marginal propensity to consume, rather than giving the printed money to investors in assets who didn’t do anything with it. QE needed to look a little more fiscal than monetary.

8. China’s pegging of the RMB to the US dollar, and the consequence of many other countries having a semi peg to the US dollar in order to remain competitive versus China. Currency wars. The RMB is the wrong price – it’s artificially too weak and therefore developed countries’ currencies are artificially too strong. This led to a race to the bottom to weaken relative to other economies, and that didn’t help anyone.

9. There was a brief moment in the quiet year or so that we had, when UK defined benefit pension funds were pretty much fully funded for the first time in years. They could have de-risked and locked in benefits for their members. Now that equity markets are nearly 20% lower, and bond yields have fallen by 1.5% (meaning assets have fallen, and liabilities risen) that’s no longer the case. Pension funds didn’t de-risk in the good times, and left millions of workers and pensioners in peril for the future.

10. Not enough shock and awe. Policy was always too incremental. The world economy needed huge injections of monetary stimulus and fiscal stimulus. The policy announcements were never enough, and confidence in policy making itself faded away as time went on. Obama would like to extend a tax cut, the Fed will do something to do with the shape of the yield curve, the ECB will buy a few Portuguese bonds, the Bank of England might print £50 billion more. The policy action was too tentative – and there wasn’t enough collaboration between policy-makers across the world.

I’m sure you’ll disagree, or have other policy errors to add. If so, you can comment below, or tweet me @bondvigilantes.

The Fed, like many central banks, has moved on from conventional to unconventional policy tools to attempt to stimulate the flagging US economy. This was manifested yesterday by the introduction of “Operation Twist”.

Operation twist involves the Fed selling $400 billion of US treasuries with maturities of 3 years or less to buy $400 billion of US treasuries with maturities between 6 and 30 years. This action is designed to drive long-term rates down to stimulate the economy. In a conventional world, one would expect the fall in long-term interest rates to boost consumption through driving refinancing of existing mortgage debt, making consumers cash rich, therefore encouraging new household formation, and some positive housing wealth effect. In a conventional world, the application of unconventional measures would presumably work.

However, this is not a conventional world. Hence the Fed might find that Operation Twist may have some unintended consequences.

The flattening of the yield curve caused by the twist, and the pre-emptive shout from Bernanke that rates will be kept low until mid-2013, will damage the banking sector. The flat yield curve and the anchoring of short-term interest rates will reduce the positive cost of carry that banks can earn, handicapping the banking system when the current crisis has the banks at its very epicentre. Additionally, by flattening the yield curve via unconventional policy actions, the leading indicator of economic growth – The Conference Board Leading Economic index – will point to a weaker economy. This might deter business planners who have historically looked at this indicator to assess the health of the economy and cause them to reduce or defer potentially stimulative investment plans. This will act as a drag on growth, precisely what the Fed is trying to avoid.

These are not conventional times, however there is a danger that central banks cannot get away from conventional thinking (especially the ECB). It is good to see the Fed is trying. Let’s hope Bernanke’s unconventional twisting of the yield curve turns out to be a net positive policy response, and not twisted thinking.

A couple of months ago I argued that the implied risk premium on emerging market (EM) debt suggested that the market was treating EM debt as a safe haven, and the market was therefore smoking crack (see here). The price action in EM hard currency since then suggests that the EM rally was indeed being artificially stimulated, and 30 year Brazil paper has since sold off almost 100 basis points versus 30 year US Treasuries.

Where it looked like EM still offered value was in FX, i.e. the overheating emerging markets needed to cool down by allowing their currencies to appreciate, while developed countries needed a sharp devaluation to restore competitiveness, restore growth and ultimately reduce debt levels. However while this is what should happen, I now have very little confidence that it actually will happen any time soon.

EM debt has shot the lights out for the best part of a decade as investors have lapped up the strong growth rates, improving debt dynamics, stronger demographics and (particularly of late) much higher yields versus developed markets. These qualities, along with strong historical performance and low historical volatility, have lured a whole wave of investors that previously didn’t have any exposure to EM local currency debt, ranging from retail investors to institutional clients, pension funds and sovereign wealth funds. While many of the oft-quoted EM benefits are very valid*, it’s important to keep an open mind to the risks facing emerging markets, which very rarely get much coverage (see blog comment on this from last year here).

Right now, the strengthening US Dollar is starting to cause a lot of problems, not so much because external debt is excessive in emerging markets (Eastern Europe is an exception), but more because one of the most crowded trades in the world is to be long EM FX (specifically Asia FX) and short the US Dollar. Another crowded (albeit slightly stickier) trade is to be long Brazilian Real against the Japanese Yen. Japanese investors have considerable exposure to emerging markets, and JP Morgan has estimated that in the last three years almost ¥6 trillion has flowed from yield-hungry Japanese investors into Brazilian bond or Brazilian Real currency overlay retail investment trusts alone, which equates to about 5% of Brazil GDP. No wonder the Brazilian authorities have struggled to contain BRL appreciation. An unwind of these long EM FX/short USD or JPY trades could cause violent moves.

The most likely cause of a stronger USD or JPY is probably a worsening of the Eurozone debt crisis, which is something we expect as regular readers are probably aware. So if Eurozone weakness and presumably the risk aversion that would accompany it continues to play out, what would be the likely effect be on EM local currency debt? Up until last week, EM local currency debt had been remarkably bullet proof in the face of global risk aversion, but this is suddenly starting to change with local currency government bonds and emerging market currencies having sold off sharply in the last week. It looks like the end investors in EM local currency debt are starting to liquidate their holdings, a suspicion strengthened by the Indonesian debt management office yesterday saying that foreign investors’ holdings of Indonesian government bonds fell from IDR 251trn on September 9th to IDR237trn on September 16th, a decline of IDR14trn or 5.6% of all foreign owned bonds in just one week. The damage this has done can be seen by Indonesian 10 year government bond yields having soared from 6.5% on September 9th to 7.4% today, while the Indonesian Rupiah has fallen 5.3% against the US Dollar over that time period.

And this is where things start getting scary. The chart below is from an excellent recent note from UBS, where they’ve taken the average reported foreign held share of local government debt for a sample of major EM countries (Indonesia, Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, Poland and Turkey). Ten years ago EM local currency debt markets were considerably smaller and almost entirely domestic owned, but foreign ownership is now at about 30%. Some may argue that 30% is still not a particularly high figure relative to most developed markets, and that’s true, but my main fear is the concentration of holders. For example, the UK government bond market is just under 50% foreign owned, and M&G is one of the larger domestic investors in the gilt market, but we still only own a bit over 1% of it – the gilt market is one of the deepest and most liquid markets in the world. In contrast, there are a handful of enormous global bond investors with a very heavy exposure to local currency emerging market debt, with some owning over 50% of individual EM sovereign bond issues. A reversal of the huge capital inflows into EM debt would result in a total lack of liquidity and significantly higher borrowing costs for emerging market countries. It won’t be just the EM sovereigns that have come to rely on these capital flows and the cheap financing this entails; EM banks and to a lesser extent EM corporates are probably in a similar position.

If the recent performance drop in EM debt markets prompts the end investor in EM debt to redeem their holdings then it could rapidly become a systemic event for emerging market economies.

* The exception being the risk return stats – the experience of the last few years should tell you that things that look great on historical efficient frontiers are bubbles and invariably end up being low return and high risk!

When I listen to my colleagues or read the English papers, the general consensus is that the Germans don’t like the Euro and don’t want to fund Greece’s bail-outs anymore. Whilst you can hardly argue against this overall impression of German public opinion, the feed-through from that to the German political landscape hasn’t necessarily reflected that popular view. In Finland and the Netherlands, Eurosceptic sentiment has created opportunities for increased political mandates for populist right-wing parties which emphasise national interests over the European “project”. But that hasn’t been the German electoral trend.

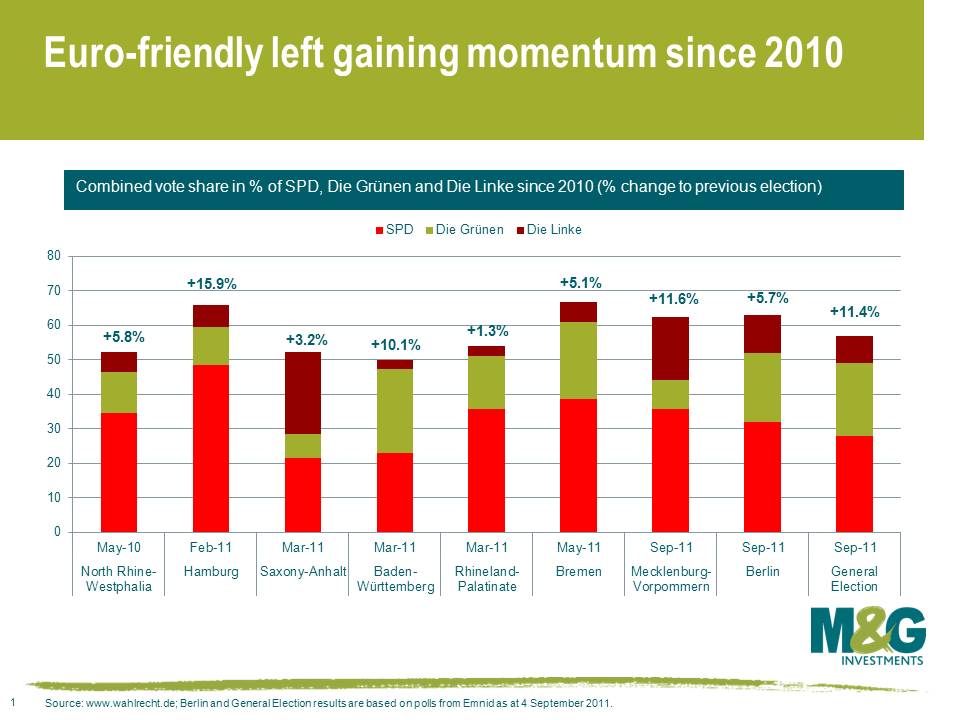

The German federal state election results since 2010 reveal that German voters have made a considerable move to the left. In the chart below, we combined the vote share of the three main parties on the left of the political centre – Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD), Die Grünen (Green Party) and Die Linke (The Left) – and added recent poll results for the Berlin election (18 September) and the general election trend. The combined vote share of these parties is in all elections above 50%, and even above 60% in Hamburg, Bremen, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and Berlin. This signifies a clear shift in political sentiment, as the comparison with the previous election results shows.

There are three significant implications of these results. First of all, the centre-right coalition parties have lost the majority in Germany’s upper house (“Bundesrat”). That is, this body will have to achieve compromise across party lines until the next major federal state elections which are not due before 2013. As the Bundesrat is meant to vote on legislation regarding European Union affairs, it is not difficult to see that recent complaints about too little involvement in the EFSF reforms will lead to more consultation with the Social Democrats and the Greens. Given the coalition government’s recent struggle to find a common position in the Euro crisis, this might not reassure the markets of a strong and clearly unified German position.

Secondly, if voters were aiming at a strengthening of Eurosceptic voices, they will be disappointed in the future. The Social Democrats and the Greens tend to be in favour of European integration and were both strong supporters of the Euro when they were in government. Even The Left, who are less enthusiastic about the Eurozone, don’t fundamentally challenge Germany’s membership.

Finally, we should keep this recent electoral trend and those two implications in mind when we are debating whether Germany is going to leave the Eurozone or going to chuck anyone else out of the inner circle. I get the feeling that the pro-Euro political powerbase in Germany is often underestimated abroad.

What a summer we have had in bond markets! The US and French bank downgrade, limited policy flexibility, aftermath of the Japan earthquake, rising commodity prices and sovereign and banking concerns already had markets on edge. A further deterioration in leading economic indicators has proved to be the straw that broke the camel’s back, leading to a sustained bout of risk aversion causing volatility, fear, and opportunity.

Richard Woolnough recently did a teleconference that covered the main themes we are currently interested in on the bond desk and how his funds are positioned. There was also an opportunity for clients and press to ask Richard questions on the outlook.

As my esteemed colleague Stefan pointed out earlier this year, we are beginning to see some attractive value emerging in the European high yield market. I thought it would be worth giving a quick update on what is being priced in and also peel back the lid on the market and take a peek inside at some of the individual high yield issuers lurking within.

Let’s start with the overall market. As of 7th September one of the main European high yield cash indices* was offering an overall gross redemption yield of 10.2%, or an additional yield of 8.9% over government bonds. Another oft quoted and traded index (the iTraxx Crossover 5-Year Index) recently traded over 750bps. Wonderful – but what does this actually mean?

At that level, the market is pricing in a 47% default rate over a 5 year period **. That means, if the market is correct, almost half of all the members of the European high yield market will slip into bankruptcy by 2016.

In my view this is an overly pessimistic view of the future, particularly when we take a look at some of the companies that this index is based on. Of course, we may not be at the lows for the European high yield market. Calling the exact bottom of any market is something only the very brave and/or foolish would do, and further problems within the Eurozone could well push the market further into the mire, but I’m willing to put my head partially on the block and state the view that we are firmly in “cheap” territory here.

Let’s take a look at some of the companies that issue high yield debt in Europe. (Full disclosure: M&G funds own bonds issued by all the companies mentioned below)

Ineos is one of the largest chemicals companies in the world with annual turnover in excess of €20bn. It is an international player with plants in North America and Europe. The company recently sold a stake in its refining business receiving $1.015bn in cash.

Capsugel was spun out of the US pharmaceuticals giant Pfizer earlier this year. The business is the global leader in the manufacture of hard gelatin capsules, selling its products to the pharmaceutical industry across the world.

Sunrise Communications is Switzerland’s second largest telecommunications company. It offers land line, broadband and mobile phone services to consumers and businesses.

Ardagh Group is an international consumer packaging company with annual turnover of around €3bn. The group operates in Europe, the US and Asia. Its main focus is food and beverage packaging, both glass and metal.

Unitymedia is the largest cable television operator in the German states of Hesse and North Rhine Westphalia, some of the most densely populated and wealthiest regions in the country.

I think it’s fair to say that these (admittedly highly subjective and cursory) examples are sensible companies with robust business models, physical assets, and in many cases would be considered “blue chips” if they were publicly listed. They are not immune to the cycle and they are all, to some extent, highly indebted, but I still think that at current yields we are being handsomely compensated for this.

Finally, it’s also worth pointing out what these businesses are not: i) They are not banks requiring large injections of capital to survive ii) They are not overly indebted sovereign nations and iii) They are not dependent on the so-called “periphery” economies for cash flow and earnings. All these are important considerations for anyone investing in the European credit markets right now.

*Merrill Lynch Euro High Yield Constrained.

** Bloomberg , assuming a 40% recovery rate.

Journalists and financial commentators have been kept very busy this year. Market participants and investors have clamoured for information on debt ceilings, credit ratings, and restructurings. 2011 looks like a year that will go down in history as one of the most volatile on record.

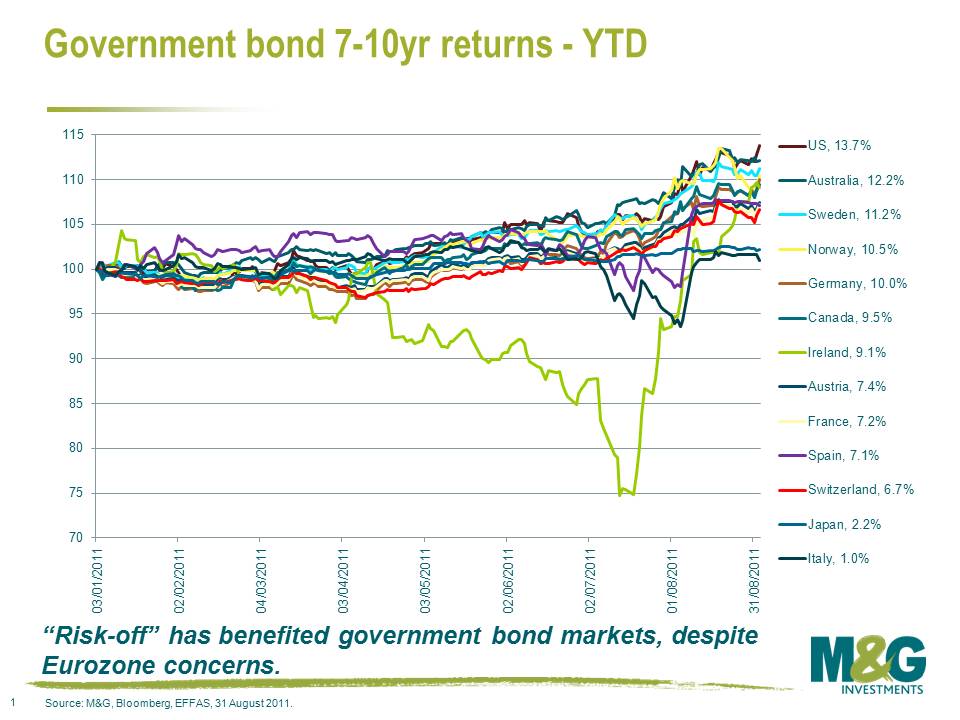

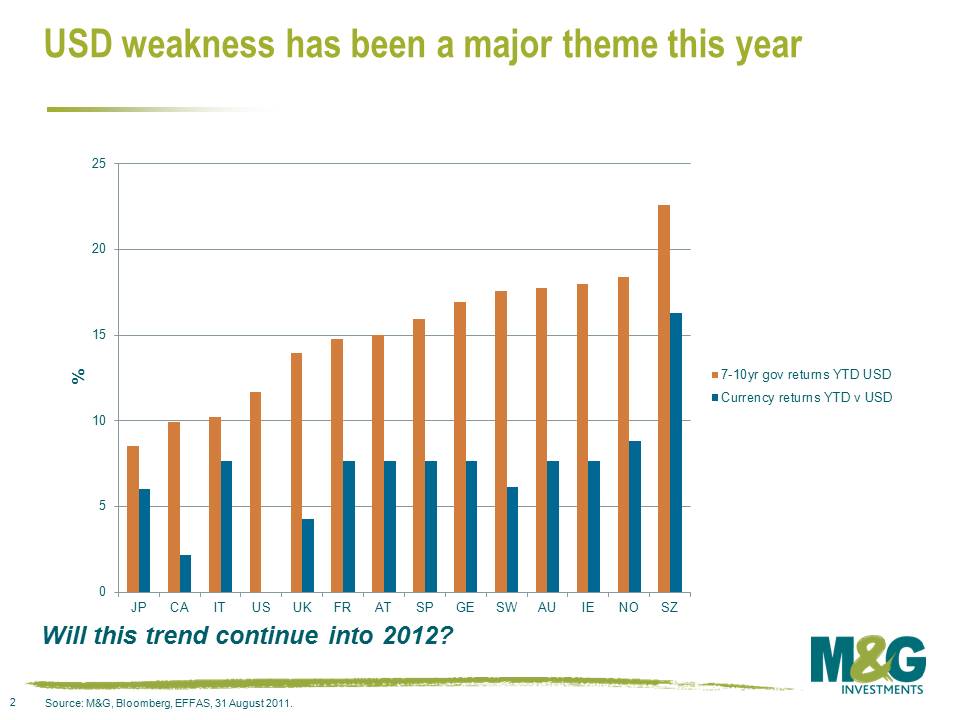

With that in mind, I thought it might be useful to focus on the actual returns within government bond markets over the course of the year. The below chart represents the total return of a 7-10 year bond index compiled by Bloomberg/EFFAS in local currency terms.

We found this analysis very interesting. Looking at the member nations of the EU, the German government bond market has been the top performer with a 10.0% return, followed by Ireland and Austria with 9.1% and 7.4% respectively. Investors in Italian government bonds have made 1.0% , despite a widening in Italian 5 year CDS from 240 to 450 basis points (currently equating to a 30% probability of a default event occurring in the next 5 years).

There are a couple of factors at play here.

Firstly, all returns are local currency. Government bond yields are major drivers of currency, so the above chart could be capturing currency strength or weakness. In order to account for the currency impact, I have re-based the returns to the world’s reserve currency – the US dollar.

We now get a clear picture of a) the US dollar weakness versus most major currencies this year and b) the impact that an increase in risk aversion will have on the returns for government bonds. Clearly, Switzerland and Norway have benefitted from solid appetite for government debt and strengthening currencies versus the USD. Time will tell whether the Swiss National Bank’s intervention in currency markets will be able to be maintained without inflation becoming a concern for the SNB. Though there might be an easier way for the Swiss to benefit from a weak currency – join the euro.

Secondly, European bonds have performed very strongly this year, despite concerns over the ability of governments to fund themselves in capital markets. These returns show that Germany remains a safe haven of choice, despite concerns that it will have to backstop weaker peripheral European nations. This has resulted in Bund yields collapsing, and peripheral European sovereign bonds have benefitted from this (as they are priced off “risk-free” bunds, in a similar way that corporates are). Spreads on peripheral sovereign debt are wide, but absolute yields have fallen.

Finally, there is a big elephant in the room, and Jean-Claude Trichet is riding it. The ECB, through its Securities Markets Programme, spent €13.3bn on sovereign bond purchases last week which brought its total holding of Eurozone government bonds to €188.6bn. Having such a large buyer in the market is obviously keeping yields on European government debt lower than equilibrium levels. The big question that we are trying to digest is just how governments and policymakers can stimulate their economies without further extraordinary monetary policy measures. It looks to us like this has been a jobless recovery, consumers are hiding, and stimulatory fiscal policy can be ruled out due to heavily indebted governments.

Mike referred to QE3 in an earlier blog, and we are starting to think that the odds we might see QE10 in the US are rising. Top of the agenda at the Bank of England’s MPC meeting will be whether it should deploy more QE. As for the ECB, it may well be forced to provide “enhanced credit support” (also known as “backdoor QE” here on the M&G bond desk) for the remainder of 2011.