Two and a half years ago, there was a real fear in the marketplace that the euro would not survive. It appeared unlikely that Greece would be able to remain in the Eurozone and that some of the larger distressed economies like Italy and Spain may follow them out. High levels of government debt, unemployment and a banking system creaking under all this pressure did not bode well for the future. The mere possibility of a Eurozone nation leaving triggered massive volatility in asset markets from government bonds to equities, as investors grappled with the consequences of such an event occurring.

Of course, the bearish forecast for Europe did not eventuate. Perceptions had shifted significantly from the darkest days of the euro crisis. Politicians and central bankers have shown significant determination in keeping the euro intact, despite often only acting at the darkest hour. In markets, confidence returned after ECB President Mario Draghi’s now famous “whatever it takes” comment and it had a real effect on government bond yields with spreads over German bunds collapsing across the Eurozone.

Unfortunately for European government bond investors, the Eurozone could re-emerge as a source of risk. The reason is, since 2011 European government and economic fundamentals have generally gotten worse and not better.

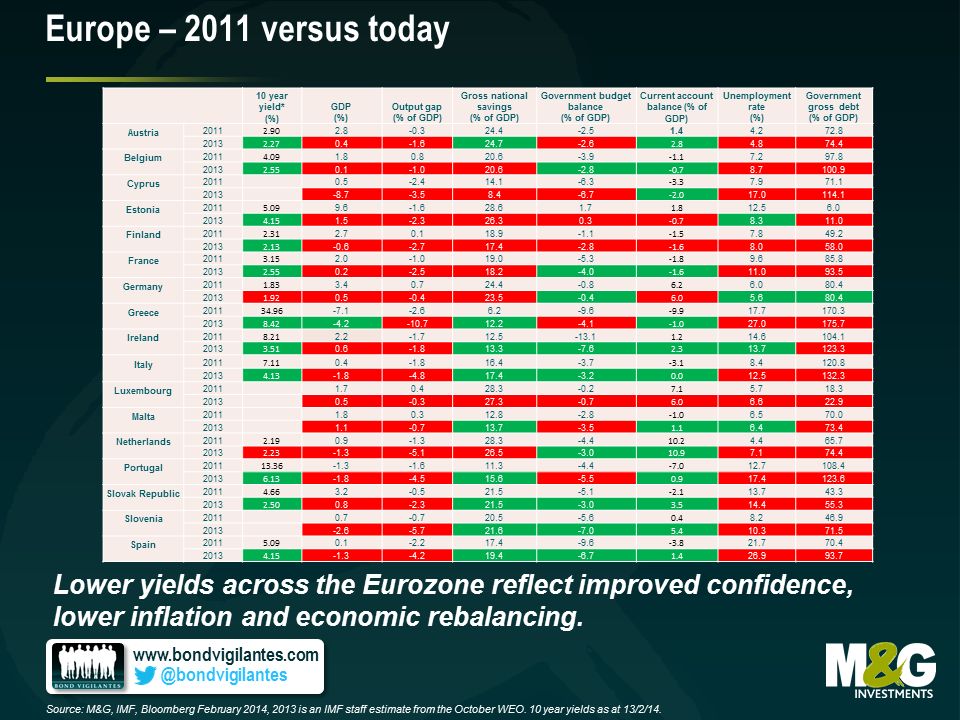

When we look at the above table – which measure fundamental indicators like total investment, the unemployment rate and gross levels of government debt to GDP from 2011 and compares it to now – we can see a lot more red (which indicates a deterioration) than green (which indicates an improvement). Yet what is striking is that apart from Germany and the Netherlands who have seen their 10 year government bond yields increase slightly, all other European nations have seen their yields fall. This is not what we would expect to see given that various metrics like GDP, the unemployment rate, output gap and government debt to GDP are actually worse now than they were at the height of the Eurozone crisis.

I can see three main reasons why yields have fallen across the Eurozone despite a worsening in the economic statistics. The first is that confidence has returned and the credit risk premium demanded by bond investors has fallen. Investors in European bonds now believe that default risk has fallen from the dark days of 2011, despite a general worsening in conditions which would imply higher – and not lower – default risk. When Draghi said the ECB would do “whatever it takes”, the market believed him.

Secondly, the inflation risk premium that investors demand has collapsed as Eurozone inflation has collapsed. Low inflation in the Eurozone is largely the result of painful internal devaluation, high unemployment and government austerity. Countries like Ireland, Portugal and Greece are feeling this the most, having experienced deflation over the last couple of years. As we can see in the table, austerity has meant that budget deficits have improved across the Eurozone, but this has also resulted in deflationary forces becoming more pronounced. Lower European inflation means higher real yields, and this has contributed to nominal yields falling or remaining low in Eurozone government bonds. However, the danger for the periphery is that lower inflation implies lower nominal growth rates, and this means even greater pressure on the Eurozone periphery’s huge debt burdens. Markets should react to lower nominal growth rates by questioning these counties’ solvency, pushing bond yields higher.

Thirdly, the other main reason that peripheral yields have converged is that there are genuine signs of rebalancing, as indicated by improving current account balances and falling unit labour costs. The majority of Eurozone nations are now running a current account surplus, including Spain, Portugal, and Ireland. Despite being locked into the single exchange rate which is arguably way too high for these countries, global competitiveness has improved and exports have increased.

There are good reasons the euro will survive. However, it is important to question whether the market is charging a high enough credit risk premium given the challenges that continue to face the Eurozone. Increasingly, bond investors need to assess the risks of deflation in Europe as well. Arguably a lot of good news is priced in to government bond markets at the moment, and we remain hesitant to lend to those European countries displaying weaker financial metrics at this point in the cycle. With the IMF recently finding “no evidence of any particular debt threshold above which medium-term growth prospects are dramatically compromised”, it suggests that there are many more important things to bond investors than the public debt/GDP ratio (like credit growth, labour markets and inflation). Public debt/GDP ratios are what investors have been fixated on since the financial crisis, but they are a lazy and incomplete way of assessing the risks in government bond markets.

There is currently a huge economic fear of deflation. This fear is basically built on the following three pillars.

First, that deflation would result in consumers delaying any purchases of goods and services as they will be cheaper tomorrow than they are today. Secondly, that debt will become unsustainable for borrowers as the debt will not be inflated away, creating defaults, recession and further deflation. And finally, that monetary policy will no longer be effective as interest rates have hit the zero bound, once again resulting in a deflationary spiral.

The first point is an example of economic theory not translating into economic practice. Individuals are not perfectly rational on timing when to buy discretionary goods. For example, people will borrow at a high interest rate to consume goods now that they could consume later at a cheaper price. One can also see how individuals constantly purchase discretionary consumer goods that are going to be cheaper and better quality in the future (for example: computers, phones, and televisions). Therefore the argument that deflation stops purchases does not hold up in the real world.

The second point that borrowers will go bust is also wrong. We have had a huge period of disinflation over the last 30 years in the G7 due to technological advances and globalisation. Yet individuals and corporates have not defaulted as their future earnings disappointed due to lower than expected inflation.

The third point that monetary policy becomes unworkable with negative inflation is harder to explore, as there are few recent real world examples. In a deflationary world, real interest rates will likely be positive which would limit the stimulatory effects of monetary policy. This is problematic, as monetary policy loses its potency at both the zero bound and if inflation is very high. This makes the job of targeting a particular inflation rate (normally 2%) much more difficult.

What should the central bank do if there is naturally low deflation, perhaps due to technological progress and globalisation? One response could be to head this off by running very loose monetary policy to stop the economy experiencing deflation, meaning the central bank would attempt to move GDP growth up from trend to hit an inflation goal. Consequences of this loose monetary policy may include a large increase in investment or an overly tight labour market. Such a policy stance would have dangers in itself, as we saw post 2001. Interest rates that were too low contributed to a credit bubble that exploded in 2008.

Price levels need to adjust relative to each other to allow the marketplace to move resources, innovate, and attempt to allocate labour and capital efficiently. We are used to this happening in a positive inflation world. If naturally good deflation is being generated maybe authorities should welcome a world of zero inflation or deflation if it is accompanied by acceptable economic growth. Central banks need to take into account real world inflationary and deflationary trends that are not a monetary phenomenon and set their policies around that. Central bankers should be as relaxed undershooting their inflation target as they are about overshooting.

Under certain circumstances central banks should be prepared to permit deflation. This includes an environment with a naturally deflating price level and acceptable economic growth. By accepting deflation, central banks may generate a more stable and efficient economic outcome in the long run.