Sprouting out: green bonds come of age

Green bonds are instruments in which proceeds are exclusively applied towards new and existing green projects – defined as activities that promote climate or other environmental sustainability purposes. They enable capital raising and investment in projects with environmental benefits. The International Capital Market Association (ICMA) set out some guidelines for issuing of green bonds in January 2014.

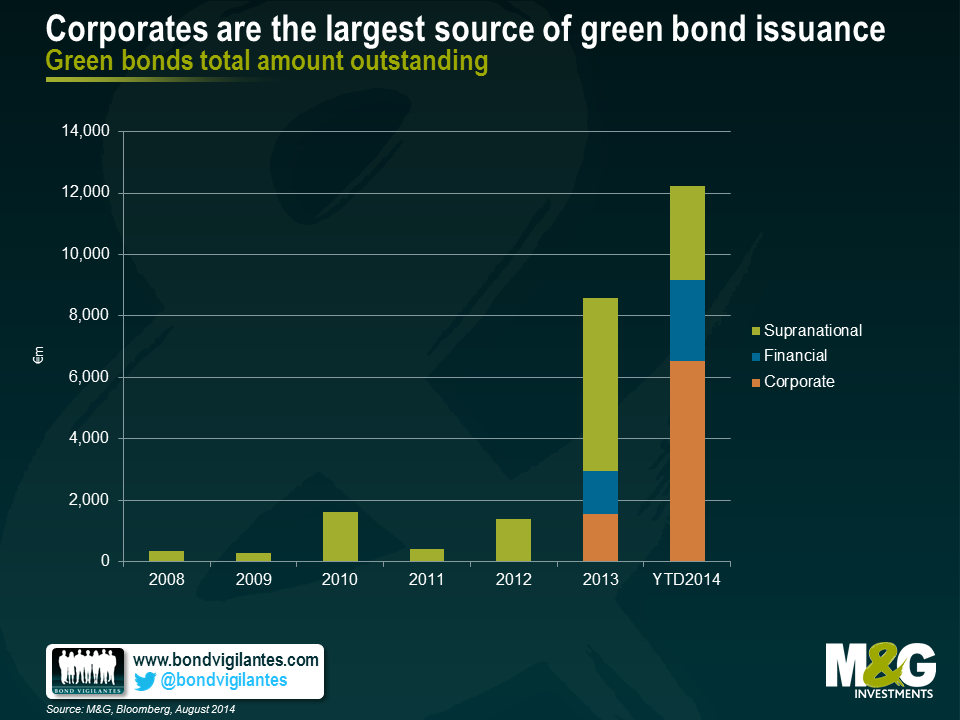

Originally dominated by supranational issuers (for example, European Investment Bank, World Bank and the European Bank for Construction and Redevelopment), financials and corporate issuers are increasingly tapping into this new source of funding.

Green corporate bonds, being a nascent asset class, are a place for many firsts. In October 2012, industrial gases company Air Liquide claimed they were the ‘first private company to issue bonds meeting the SRI investors’ criteria’. This bond predated the Green Bond Principles, and technically may not be a green bond, but is noteworthy in having been ‘mostly placed with Socially Responsible Investor (SRI) mandated issuers’. Since then, we’ve had French utility EDF in November 2013 announce ‘the issuance of the first corporate Green Bond’, although that title may just (by a couple of days) go to the Swedish property company Vasakronan. More recently we’ve had consumer goods company Unilever announce in March 2014 ‘Unilever’s green sustainability bond is the first green bond in the sterling market, and the first by a company in the FMCG sector’.

It is apparent that corporate issuers are keen to spur the development of the green bond market as an alternative funding source and, in doing so, raise awareness of the environmental issues they face. Looking at the chart below shows that corporates are now the single largest source of green bond issuance. Whilst it’s clear that issuers and investors both earn brownie (greenie?) points in terms of enhanced reputation for their involvement and support of sustainable projects, green bonds lack a binding internationally recognised definition, they merely adhere to a voluntary set of guidelines.

One of the structural features of green bonds is that they are often issued off existing Euro Medium Term Note (EMTN) programs and guaranteed by the parent company. Cash flows that service bonds come from the issuer, therefore benefiting from the overall cash flows of the corporate, not just the project that is being funded. It is not surprising, therefore, that the credit rating of these bonds is in line with other bonds issued by the same issuer. This dislocation does, however, mean that investors are not able to identify the cash flows from the underlying project.

Corporate bonds issuers often bracket their use of proceeds into ‘general corporate purposes’, which rarely tells investors much about how or where the proceeds are to be used. Is it, for example, for refinancing, M&A, capital expenditure or share buybacks? In contrast, one of the cornerstones of a green bond is that the use of proceeds is defined in the legal documentation of the security, which should bring a degree of transparency. I say degree because, in practice, once the proceeds are deployed the investor may have limited information on the progress of the project and the extent to which it is meeting environmental targets. For instance, are bond proceeds for the specified project leading to an identifiable reduction in greenhouse gases, water and waste?

There is a certain asymmetry in green credentials required between issuers and investors. For an entity to issue a green bond they have to abide by the principles as outlined by the ICMA. Alongside use of proceeds, these also include project evaluation and selection, reporting, as well as management of proceeds. The latter includes a suggestion to enhance the environmental integrity of the instrument through the use of an external auditor, an independent verifier or as some have called it, a Socially Responsible Investment (SRI) rating agency. Yet with so much stringency on the issuer side, there seems to be no limitation on which bonds funds are able to participate in owning such an issue. Whilst issuers are often citing a desire to diversify their funding sources and attract SRI and Environmental Social and Governance (ESG) conscious investors seeking sustainable (both from a cash flow and environmental perspective) fixed-income instruments, the investors themselves do not necessarily need to have such a green bill of health.

Indeed, even a bond issued in a ‘green wrapper’ may not satisfy certain SRI funds which may argue, rightly or wrongly, for example, that EDF is using cash flows generated through nuclear power activities to pay coupons on its green bond. Another angle on this would be to say that environmental projects are receiving credit enhancement through use of corporate cash flows to prop-up investment in green initiatives. Regardless, the burden remains with the investor to determine how green the bond is. The rating agencies have so far not waded into the argument by assigning a relative ranking of ‘greenness’.

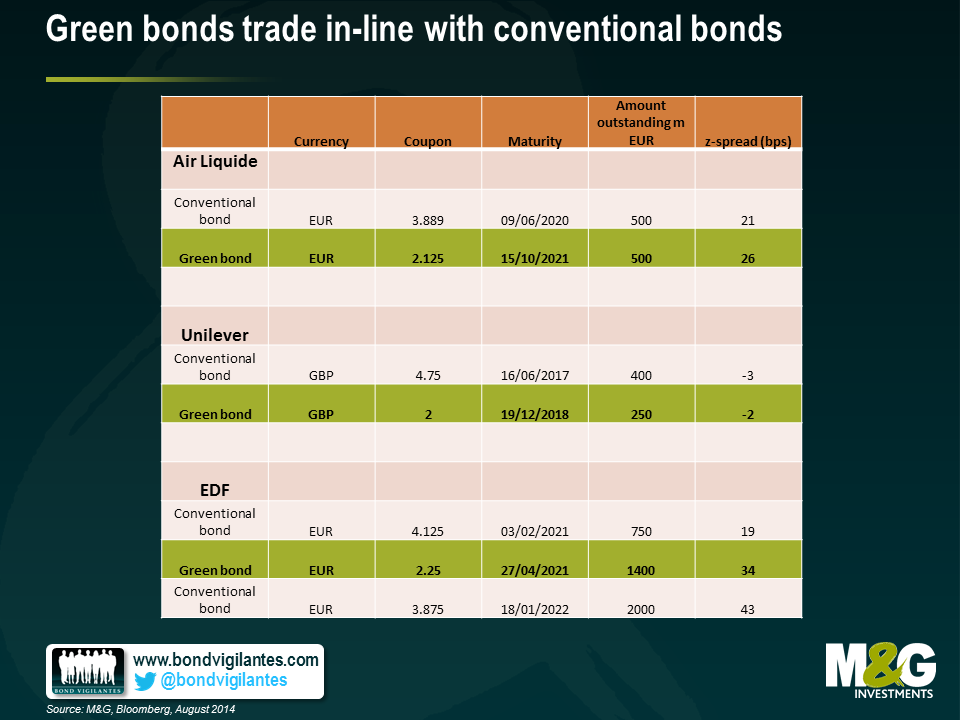

Finally, looking at a few examples of corporate green bond issuers in the table below, it appears that the pricing of green bonds on the secondary market is in line with other (‘non-green’) issues, which to us makes sense given the structural and cash flow arguments mentioned.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

17 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox