It is the time of year when the geese begin their long flight south to avoid the hellish northern European climate. In markets we are always on the look out for flocking and herd mentality. Sometimes as an investor you want to run with the herd and sometimes you want to observe the herd mentality from afar.

And it’s not just the geese who are looking for a change of scenery. Over the last few weeks some of the biggest names at British banks have announced they will be standing aside. John Varley (CEO of Barclays), Stephen Green (Chairman of HSBC) and Eric Daniels (CEO of Lloyds) have all decided to fly the coop. This has got me thinking; do these gaggle of astute top bankers, like the geese, know some inclement weather is on the way and are getting out while the going is still relatively good?

It’s that time of year once again – school holidays are over and the children are going back to work. This feels very much the same in the grown up (?) world of investment. This year’s questions and tests look as though they are going to be trickier than usual. After all, the financial headmaster Ben Bernanke has just warned that conditions are unusually uncertain.

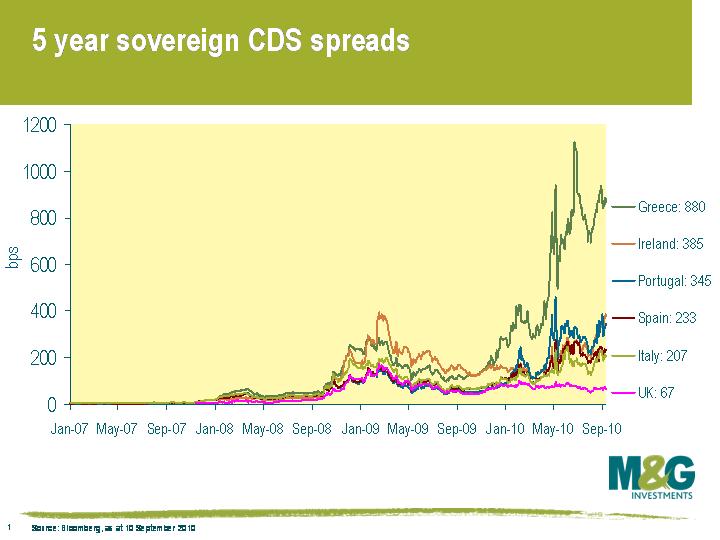

The move from the summer lull to the rigours of testing examination is no more acute than the pressure that has been reapplied to sovereign credits in Europe. The European authorities have generally responded to these challenges by a series of increasingly significant policy measures, but this chart shows they have still not solved the problem. Let’s go back to the economics class and study why their unprecedented actions have failed to soothe the markets.

When I first started studying economics as a 13 year old I didn’t have a professor Ben Bernanke. I had a “professor” Cec Thompson. He was not a real professor, but had acquired the nickname when educating himself while playing professional rugby league, where he reached the heights of playing internationally for Great Britain. Unlike Doctor Greenspan, his autobiography is a very good read. The first economic lesson I can remember that he gave was based on the price discovery and market clearing process in a simple economic example called the hog cycle. This introduced me to the concept of relative price change and market pricing, teaching us the principle of the invisible hand.

The current problems of the European periphery appear to centre on the concept of a single currency zone. By moving to a single currency 10 years ago, a simple and effective method of price discovery and market adjustments was removed from the labour and capital markets. Looking back this seems to have resulted in too much capital at too low a rate being deployed in the European tiger economies – boom and bust on a grand scale. How are we to solve this problem?

In order to make labour and capital markets efficient again, the simple option would be to reintroduce national currencies. The mechanism for doing this is non-existent, and their reintroduction and failure of the euro in this scenario is seen as worse than the current problems we face. The solution is to find a way to reintroduce national currencies, and the invisible hand, in the least damaging way possible. I have talked about this before at length, where the introduction of a new euro (the “Neuro”) would have to be done in a planned way and with a share of the shock born by savers and lenders. In the short term this would still be painful. But the long term alternative of an increasingly pressurised Eurozone, with the peripheral economies unable to adjust due to a lack of efficient market mechanisms, will turn out to be a chronic rather than a temporary problem in my opinion.

In a modern society, labour and capital should be allocated by a combination of governments and the free markets. Removing the efficient, invisible hand provided by national currencies and replacing it with political decision making as occurred with the euro was a big step. The result was political rather than economic responses to the stresses within the Eurozone, as typified by a Jean-Claude Trichet interview in today’s Financial Times, where he argues that in order to get markets to work we need to think about further strengthening the political framework.

Education is not only about doing things right, but learning from mistakes. Let’s hope that the experiment of the euro – which is just getting past its infancy – develops into a successful means of developing the economic fortunes of the Eurozone, and not a dysfunctional teenager in the years ahead.

In all financial and commodity markets the big figure (the first part of the price) is referred to as the handle. This allows verbally quicker and more accurate trading (see this classic Two Ronnies sketch) as the handle does not need to be mentioned in every transaction. In the bond markets the handle from a yield perspective is the first big figure, so when the yield on a security is 4.5%, the handle would be 4. The ongoing bull market in the UK means there are currently no conventional gilts outstanding with a yield greater than, and therefore with a handle of, 4.

Like the stock market’s focus on the Dow 10,000 level, bond investors also focus on significant round number levels. The psychology of hitting new lows in yields takes time for the market to get its head round, while the financial implications for issuers and investors can be enormous. The loss of the 4 handle in long dated conventional UK bonds has been replicated by the loss of the 4 , 3, and 2 handles of long dated US, German, and Japanese government bonds respectively over the last three months.

The implications of these new low yields is substantial. For an investor such as a pension fund that is short longer dated liabilities, the funding gap increases, putting it under pressure to buy more bonds at a lower yield and higher price due to the mismatch of assets and liabilities. While for issuers like the government it means they are better able to service their debt, and will need to issue less to meet their funding needs. Thus the psychology of the shift below 4 percent is compounded in favour of bulls versus bears by the realities of market positioning.

We first started writing about the credit crunch 3 years ago (see August 2007). Since then, short-term interest rates in the USA, Europe and the UK have collapsed to near zero. Ten year government bond yields across the respective economies have fallen by around two percent. Whilst the fall in interest rates and yields has been a great present for government bond investors, the global economy has been suffering one of its worst recessions since World War II. But enough history. What about the future?

Financial market values at a simple level are driven by two basic themes – long term trend following and shorter term mean-reverting price action. This is also generally true of economies. Looking back over the past 50 years, we have seen a period of strongly upward trending economic growth within which there has been cyclical up and downturns. It has been the job of the modern fund manager from a stock selection point of view to identify if individual stocks and sectors are in a long term trend or mean reverting mode, whilst from the macro point of view they have just had to focus on where the economic cycle is within its permanent uptrend.

The challenge investors now face is to add another dimension to this traditional thinking. What if economic growth is no longer permanently upward trending? What if the trend of growing economies in the developed world is coming to an end?

The credit crunch is now three years old. Where is the upturn in economic growth? On Tuesday the US Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) acknowledged that we were not there yet and have decided to reinvest the assets they purchased through quantitative easing. This is an acknowledgement that it is still not time to start tightening monetary policy. The FOMC have used up all their bullets in the interest rate armoury by reducing interest rates to near zero percent, encouraged the huge fiscal pump priming undertaken by government (Republicans and Democrats alike), and used unconventional measures of quantitative easing. These policies have been replicated to a lesser or greater degree within the G7 and beyond. And despite all of these extraordinary measures, the global economic recovery remains in doubt. It is fair to say that those central banks around the world that are currently running ultra-easy monetary policy will continue to do so for some time to come.

The interesting question now is whether we are in a long term structural change in economic growth prospects. Maybe we are no longer just in a cyclical downturn. It has been 3 years since the credit crunch began, and the arguments that this is not a normal economic cycle are becoming more compelling. If this is the case, it will be a long term growth environment that the Western world governments, central bankers, and fund managers have never seen before in their working lives. A challenge indeed.

It appears that developments have moved on quite dramatically since my last blog on the market describing the political dynamics between governments and capitalist investors (insert speculators here!). There are a number of key points in the latest round of sparring that I think should be highlighted.

Firstly, European governments have taken the kind of action speculators respect and can’t ignore. European authorities shocked markets last week by announcing a huge €750bn bailout fund for the eurozone . Additionally, the European Central Bank said that it was ready to purchase eurozone government and private debt to ensure depth and liquidity in markets. The ECB has noted that it will sterilise the bond purchases, meaning that it will not quantitatively expand the money supply like in the UK. After an initial bout of investor exuberance the enthusiasm of market participants has waned since the announcement. It has dawned on everyone that Europe still faces significant hurdles and there are growing fears that the situation could send the global economy back into recession.

Secondly, as Stefan wrote yesterday, the German authorities have decided to attack market disorder and valuations by banning naked short selling of European government bonds, credit default swaps, and some German financial securities. This is the type of action that speculators can not ignore, and will not respect. The move by the German authorities has caused confusion and uncertainty in markets. France was quick to say that it will not follow suit and said these measures could actually hamper market liquidity. The move raises more questions than answers. For example, how will it be applied? Who does it apply to? Which jurisdiction does it apply to? How will it be monitored? How will investors be prosecuted and fined if found guilty of short selling? I am sure you can think of even more.

These are serious questions for market participants. Unfortunately, markets do not close while we await the answers of the above. The effect will be to increase uncertainty, make markets less efficient, and could therefore possibly increase risk premiums. One would think that these results are the opposite of what the authorities are trying to achieve.

As I write, trying to understand the above new set of rules is vexing many market participants. I think the issue will be that if governments start to try to fix the price of markets at a set level through political and legal policy, the invisible hand of the markets could well be inefficiently bound. Increasing regulation in Europe will see investors increasingly look at other markets to invest in. I hope the European governments realise that they are still going to need to borrow in the coming months and years, and to do that they will need a big, deep, and liquid market.

Democratic governments are designed and exist to promote and protect the interests of their population. Thus they tend to be described as “good”. Capitalists are seen to be out for themselves and therefore acting in their own selfish interests. They are often described as “bad”. However, in order to have a prosperous society one has to combine the socialism and fairness of democracy with the efficiency and ruthlessness of capitalism.

These two forces come together in the government bond market. On one side is the collective need to borrow to provide for your citizens needs (health, education, defence, etc) and on the other are capitalists who provide the finance for government spending. These capitalists can be described as either investors or speculators.

Investors are generally seen as good capitalists, while speculators are seen as bad capitalists. This line of thinking has once again come to prominence with the market’s attempts to value Greek debt, with holders of the debt who think it is undervalued described as benevolent investors, while economic agents who think the debt is overvalued (expressing their view through credit default swaps) described as devilish speculators.

European governments are now looking to see how they can regulate speculative investors who have used CDS to express a negative view on Greece’s ability to pay its debts. They argue that Greek government bondholders might actually want to see Greece default on its debt due to their holding of CDSs. It has been noted that CDS holders might be incentivised into pushing for Greece to enter default. Additionally – because the CDS market is over-the-counter – there is no way of finding out who the protection buyers and sellers are, adding to uncertainty and volatility in markets. The investment community counters these arguments by saying it should have the right through CDS to promote the efficient allocation of capital.

Putting the various arguments aside, let’s assume the governments win – after all, they regulate the market and can determine what contracts are legal. This banning of CDS would eliminate the tool of CDS for speculators to express a negative view, but would also eliminate the potential for speculators (investors) to express a positive view. If it is seen that the banning of negative CDS trades is a net positive for governments and society then governments could then move a step further and seek to ban the shorting of government bonds physically or through the use of the futures market. If that works then governments could progress to stop the shorting of national currencies as that position is the most aggressive step capitalists can take against a nation state. If that works then governments could stop criticism of their national finances. If that works… I think you know where we would end up!

This is the essential conflict between the state and the individual; are you an individual/speculator who is up to no good, or are you an individual/speculator who challenges the status quo for good? Should CDS on governments be transparent and not abused? Yes. Should it be banned? No. The CDS market should be a fair and level playing field. If governments think that CDS are mispriced then they should take the same response as they do in the FX market i.e. behave responsibly, influence the debate verbally, and then strongly intervene with the only medicine speculative capitalists respect, real money.

Today the date for the UK general election was announced. May the 6th it is. It is once again time for British citizens to place their X to choose the future direction of the country. From a UK bond investor’s perspective this could well be a significant catalyst in determining the future direction of UK economic policy too.

Although the latest polls are quite close, it seems likely we’ll get a new government. The question is what kind of government? And will the decision be made on the 6th May or will we be left with a hung parliament? A hung parliament is currently perceived to be a disaster – how can you have a catalyst for change when you have no one in charge?

The uncertainty of the result would be compounded by whether parliament is hanging to the left or to the right, and if you can excuse the horrendous image, how well hung parliament is! The fate of parliament would then be decided by the Liberal Democrats. What are they likely to do? They are likely to pursue the policies they believe in and to work with the mandated larger party, which due to the bipolar nature of the UK system could be either party, the one with the most seats, or the one with the most votes.

The critical thing about the UK election from a bond (and currency) investor’s perspective is the resolving of uncertainty over the future of economic policy. This is where the Liberal Democrats can increase or remove uncertainty and thereby extend or remove the UK risk premium based around the election. I think the latter alternative is the obvious political choice.

The reason they need to do that can be expressed in a less highbrow way. The biggest annual vote in the UK is probably the X factor. Imagine the final of X factor with three candidates on stage, the simply red Gordon Brown, the blue aficionado David Cameron, and the Bruce Springsteen inspired Nick Clegg who is in charge of their fates and appears to therefore be the Boss. Well, the one thing that Clegg can not do (despite being Born to Run?) is ask the electorate to vote again, because as the weakest link he would be eliminated if the electorate was forced to choose between the other two parties in traditional two party British political fashion, resulting in the Liberal Democrats losing seats and influence.

Therefore a hung parliament is not likely to lead to further indecision, and delaying of policy implementation, but like a clear victory, even a hung parliament should provide a catalyst for change, and a collapse in risk premiums that could benefit both Sterling and the Gilt market.

According to many market commentators, the UK debt market is looking sick and is at a critical juncture. It is amongst the most unloved government markets in the developed world, which is understandable given the British inability to save in the boom times. Now there is justifiable scepticism that markets will not be able to absorb the forthcoming huge government debt issuance once the Bank of England stops providing life support to the gilt market when it ends the quantitative easing program.

This consensus view is typified in PIMCO’s monthly investment outlook in which the UK bond market is singled out as a market that must be avoided. In their opinion, the gilt market is resting on a bed of nitroglycerin. PIMCO point to the UK’s relatively high level of government debt, potential for sterling to fall and domestic accounting standards that have driven real yields on long dated inflation linked bonds to exceptionally low levels.

We agree these are issues that face the UK economy and have commented on these points previously. However, like any consensus, it makes sense to investigate if this is correct, priced in, and when it might come to an end.

Firstly, the IMF forecasts that for 2009 that the UK government will have a relatively large annual deficit of -11.5% of GDP, which is below that of the USA (-12.5%) but almost triple Germany’s government deficit (-4.2%). However the UK’s total outstanding gross debt stands at 68.7% of GDP, which compares favourably with the USA (84.8%) and Germany (78.7%). The UK government has responded in aggressive Keynesian fashion to the downturn, if this medicine works then the action will be short term in its nature and will not leave the UK with a permanent debt burden, or the increase in debt could alternately be curtailed by the arrival of a more fiscally stringent government in this year’s election. The UK has very little foreign debt and has been prudent by having the longest maturity debt profile in the G7. Outstanding debt and re-financing needs would therefore appear relatively manageable on an international basis. Not all outcomes will be bad.

Secondly, with regard to fears that our exchange rate could fall, the exchange rate has already collapsed by 22% on a trade weighted basis since 31 July 07. So a lot of the necessary adjustment has already taken place. This adjustment process is very beneficial for an open economy such as the UK, especially when many of our trading partners are locked into using the relatively strong Euro currency. By having a flexible currency and control over domestic interest rates, the UK is arguably in as good a position as anyone to grow our way out of our debt problem.

Finally, accounting standards have indeed distorted gilt yields as we have previously mentioned here. However, this accounting standard is designed to improve company accounts in terms of disclosing assets and liabilities of company pension schemes and this is surely a good accounting standard that should be adopted by many other regulators. The fact that better pension regulation in the UK results in lower long term rates makes long dated bonds – especially UK linkers – look dear internationally. But this dampening influence on gilt yields is a distortion that is likely to persist unless the regulation and the accounting oversight of this significant employee benefit are changed.

The view that the UK gilt market is one to avoid has some punch in the short term, but the consensus is exaggerating the risks the UK gilt market faces. Even if one agrees with the consensus, it is important to see if this view is priced into markets and when this will eventually come to an end. I agree with the direction of the consensus, absorbing that much new supply will be negative for gilts in the short term. However in the longer term the UK has the chance to adjust to the crisis through fiscal stimulus, financial reform and a falling exchange rate that might well provide the medicine required. The consensus that a bed of nitroglycerin is a dangerous place to rest like any consensus view should be challenged. Don’t forget, a bed of nitroglycerin could be exactly what the sick UK economy needs as it is one of the oldest and most useful drugs for restoring patients with heart disease back to good health!

There has been a lot of anguish and complaints from bankers about Obama’s tax on banks, and complaining why they have been singled out. Some of this is the usual self interested financial posturing (they are bankers!), some of it is in response to unfair political criticism, typified by last week’s focused grilling of Lloyd Blankfein, a successful CEO of a successful bank (Goldman Sachs). Ignoring the emotional sides of the argument what about the tax itself?

In principle it looks like a fair idea. If the government acts as a lender of last resort, financed by the tax payer, then the beneficiary of that guarantee, the banks’ shareholders, employees, and customers should share the fee. The difficulty of course is implementing the tax in a global financial system, and determining the appropriate fee. Fortunately for Obama, the threat of relocating your banking operations outside the biggest capital market in the world is not credible so implementation should be successful. Setting the level is a different matter, too low and the state effectively subsidises risk taking, too high and the state stops appropriate risk taking. However, this should not stop attempts to set an appropriate rate, as having no insurance indemnity will eventually distort markets.

A tax policy on its own is not the only answer to pricing risk correctly, you have that other government tool to help or interfere in the economy (depending on your political view): regulation. After all if you’re an insurance company providing insurance you tend to set out the terms and conditions to your customer to stop reckless behaviour. That’s one of the things that financial regulation sets out to achieve, and indeed if done successfully mitigates the need for setting an insurance premium. However insurers and regulators have to work closely in tandem, otherwise the risk takers will find ways round the regulations.

Given the chaos that has occurred following the run on Northern Rock, the bail out of major banks around the world, and the Icelandic bank failures, you would have expected the regulator, the lender of last resort, and the tax payer to have learnt a thing or two, and to stop the danger of free riding of bank shareholders, bank employees, and bank customers. However on reading the papers this weekend I came across an article about a one year sterling high yielding deposit account paying 4%. The catches to this offer referred to in the article included a lack of an https address and padlock symbol on the bank site, and an unproven customer service. On the other hand the article referred to the fact that account holders would be fully covered for £50,000 under the UK’s Financial Services Compensation Scheme. Pre October 2007, the compensation scheme used to extend to 100% of the first £2,000, and a further 90% would be guaranteed from £2,000 to £35,000 (so customers would take some degree of risk if a bank failed). On checking the website of the bank this morning to investigate further I was greeted with the comment that the website was being upgraded due to the unprecedented demand for its online deposit product. A rate of 4%, 8 times the official Bank Rate, where can you invest to get a relatively low risk free return on that type of cost of funding? Even Lloyd Blankfein and his team would have difficulties.

Isn’t there a danger that we have made no progress from where we were 2 years ago with Icesave, and the Icelandic banks paying up for deposits, lending them on to high yielding risky ventures? Don’t worry customer, the taxpayer will bail you out! Whether you’re right wing and dislike state subsidies, or left wing and hate distribution of tax revenues from the poor to the rich this does not look politically right. Things need to change, on the insurance front progress has been made, on the regulation front work still needs to be done, and sadly in the UK the incentive to take risk, with your deposits and tax payer money, has been increased.

Earlier today the Bank of England announced that along with keeping the bank rate at 0.5% it is to increase the QE program by a further £25bn over the next 3 months. Whilst an increase was somewhat expected by the market gilts have sold off, the yield on the 3 3/4 2019 rose to 4% earlier as it seems to have expected a larger commitment. Even though we had a GDP print of -0.4% recently it seems the Bank is laying the groundwork for stepping away from the bond purchases. Considering they have bought back £175bn worth of gilts since March and now they are planning to do £25bn over the next 3 months it definitely feels like they are turning down the dial. By my basic calculations the rate of increase has reduced by roughly 70% (originally they were buying £25bn per month and now that has fallen to £8bn per month). Hopefully this reduction will strike the right balance between helping the economy get back on its feet and allowing the Bank to hit its inflation target. We should get further colour on their thinking when the quarterly inflation report is released on the 11th.

We had a number of correct entries to our QE prediction competition so in the interest of fairness we have drawn a name out of a hat. The winner is Peter Lowe at Smith & Williamson. Congratulations and we hope you enjoy the book.