A letter from Ireland to M&G’s Bond Vigilantes

Dear Bond Vigilantes,

The small nation of Ireland has received more than its fair share of press since the credit crunch started three years ago. The financial crisis has not been kind to the Irish economy, with the collapse of the Irish property bubble having a profound impact on citizen’s net wealth and psyche. In fact, Ireland was the first country in the EU to officially enter recession. As recently as this week, Standard & Poor’s downgraded Ireland’s credit rating to AA-, its lowest since 1995. The “Celtic Tiger” was shot and wounded when Lehman Brothers collapsed.

I had previously worked in Dublin from 2007 until mid 2009 and saw the effects first hand that the recession was having. Union strikes, vacant shop fronts and alarming headlines in the newspapers were becoming an all too regular occurrence. On one occasion, an estimated 500 people queued for 15 jobs at Londis, a convenience store chain. The line of people stretched from St. Stephen’s Green to halfway down Grafton Street. Things were truly dire, and an air of uncertainty was a constant presence in conversations with colleagues, friends and family.

With these memories fresh in my mind I headed back to Ireland with my brother and old man, with a view of sampling some of the Guinness and scenery. But first a bit of background.

The problems with the Irish economy are well known. So are the measures the Irish authorities have undertaken to consolidate the governments’ finances. Sizeable cuts to public sector pay and social welfare payments have helped to restore confidence amongst the global policy community and international financial markets. After a severe decline in growth in 2008 and 2009, the Irish economy has stabilised in 2010 and is now growing again.

But the path from crisis to stability and recovery is likely to be narrow and rocky. Ireland will likely rely on exports and tourism to lead the economic recovery. As Ireland is part of the European Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), they cannot rely on a depreciation of the euro in order to become internationally competitive. The Irish need to become more productive and have to reduce wage costs. Irish banks remain a source of uncertainty with higher than expected losses, uncertainties in global regulatory trends, and limited access to funding hurting the Irish financial system.

As we travelled around Ireland, speaking to the locals, drinking with the locals, having the craic with the locals, the state of the economy would often come up. In these chats, a few themes kept re-occurring. These themes were unemployment, emigration, house prices, and the banks.

The unemployment rate in Ireland deteriorated from 4.5% in 2007 to 13.0% in 2010. This large increase in unemployment reflects significant structural changes in the Irish economy. Unsurprisingly, the construction sector was a huge employer of people in Ireland and with the house price crash it is unlikely that these jobs will come back. Looking at the unemployment data in Ireland, it is a concern that labour participation has fallen among older males as they may find it increasingly difficult to find work in the future as the economy recovers. Persistent unemployment is going to be a huge challenge for the Irish authorities.

For the first time in many years, Ireland is experiencing net outward migration. In this downturn, immigrants from Central and Eastern Europe have left Ireland in droves, whilst the Irish themselves have emigrated to places like Australia, Canada and the UK. Without emigration, the IMF estimates that the unemployment rate could have been as much as 2 percentage points higher. The concern is that Ireland is experiencing a “brain-drain” (present company excluded), and the Irish education system is effectively exporting a highly skilled and educated workforce (one that will pay taxes in their new place of residence).

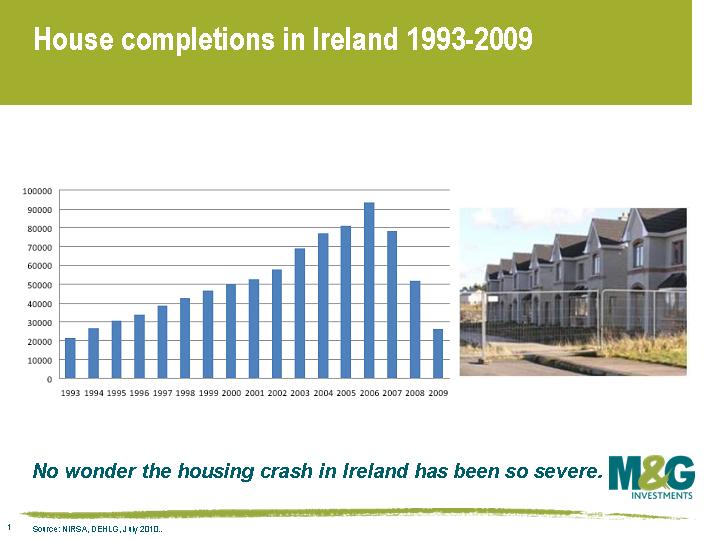

Driving through the towns of Ireland we often encountered huge estates of houses that had been completed to varying degrees. These have been named “ghost estates” by the Irish. House prices shot up in Ireland during the boom years but were also accompanied by a construction boom, leading to a rapid increase in the supply of available housing (as seen in the accompanying chart), new shopping centres, business parks, and hotel developments. The dependence on the property market as a key driver of the economy and a vital source of tax revenue during the “Celtic Tiger” years has left the country with a set of serious problems that may take a generation or more to resolve. Certainly banks have tightened lending for new construction projects markedly, and it appears that there is little need for any new houses to be built in the immediate future. Some commentators have gone so far as to say the ghost estates need to be knocked down.

The National Asset Management Agency (NAMA) was a constant source of topic on the radio and in the Irish newspapers. The Irish government set up NAMA to transfer distressed property developments from the books of banks into a “bad bank”. By February 2011, NAMA will hold €81 billion of toxic debt which is roughly equal to 50% of Ireland’s GDP. The Irish have not bought into the idea of NAMA, with many suggesting that the losses incurred by the “cowboys” at the banks should not be offloaded onto the Irish taxpayer. Pure and simple NAMA is an experiment and only time will tell whether it was the right thing to do.

On the austerity measures that Ireland have introduced, I think a quote from The Daily Telegraph’s Ambrose Evans-Pritchard sums up the views of the Irish pretty well:

“Dublin has played by the book. It has taken pre-emptive steps to please the markets and the EU. It has done an IMF job without the IMF. Indeed, is has gone further than the IMF would have dared to go. It has imposed draconian austerity measures. The solidarity of the country has been remarkable. There have been no riots, and no terrorist threats. Yet as of today it is paying 5.48% to borrow for ten years, or near 8% in real terms once deflation is factored in. This is crippling and puts the country on an unsustainable debt trajectory if it lasts for long. Yet Greece is able to borrow from the EU at 5% and from the IMF at a staggered rate far below.”

It is particularly interesting if we think about the austerity measures that Ireland have had to implement and then try to determine what the possible impact that budget tightening might be on the UK and a major European country like Spain. Through assertive steps to tackle the budget problems head-on, Irish policymakers have gained significant credibility. But that is not enough. Retaining credibility will require strong commitment and active risk management. The markets view ambitious fiscal consolidation plans in Ireland, Spain and the UK as appropriate and these plans will demand years of tight budgetary control. If new governments are elected, will they continue to retain a tight control of government spending in the face of rising public discontent?

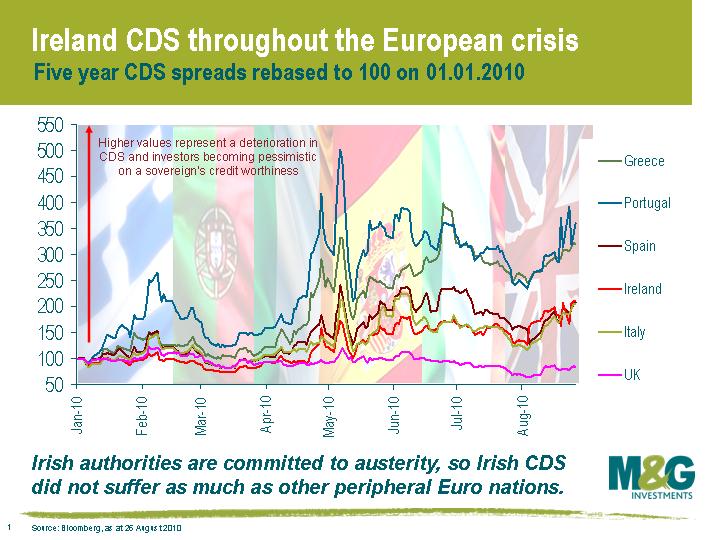

The return to a self-sustaining economic recovery, with lower levels of government expenditure, is going to take time in the respective economies. In the interim, unforeseen fiscal demands may occur and policymakers have limited bullets left in the fiscal gun. With limited fiscal resources, maintaining a steady policy course will be required to minimise risks and sustain market confidence. We saw that the market retained some confidence in Ireland during the Greek sovereign crisis in May, when CDS for other European peripheral nations widened relative to Ireland CDS.

More recently, CDS for European nations has been widening due to concerns about the ability of sovereigns to issue debt and a slowdown in the global economic recovery. CDS for the UK has been stable and confirms the market’s view that the UK is relatively risk free.

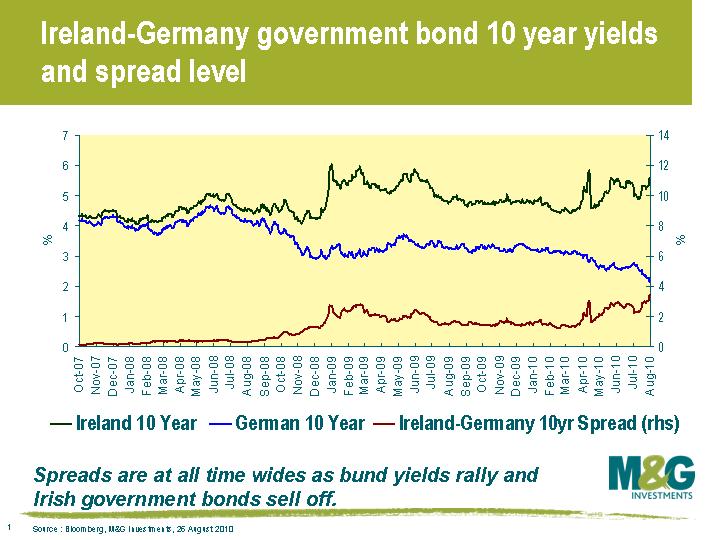

The Irish have a tough task on their hands, no doubt about it. The restaurants and pubs are quieter than they used to be and the price of a pint of Guinness has come down a little (around €3.80 on average at the pubs I visited). In many ways, the Irish authorities have done everything that was required of them and this is pleasing some market participants. Mike Riddell bought some Irish 10 year government bonds on Wednesday after Ireland was downgraded, reflecting his view that the authorities remain committed to austerity and that the bonds are attractive at these valuations. Irish 10 year government bonds are currently yielding 5.60% compared to 2.16% for German 10 year bunds. The spread of Irish government bonds to German bunds is currently 3.44% which is a record level, so investors that are willing to take more risk are being compensated well to do so. Interestingly, the ECB waded into the market and bought some Irish 10 year bonds as well on Wednesday.

There is also a lesson in Ireland’s experience for emerging market nations, particularly in Central and Eastern Europe. In the 1980s Ireland was a relatively poor, peripheral nation on the edge of Europe with a weak economy. Foreign direct investment was mainly in low-skilled, branch plant manufacturing. The 1990s saw Ireland transform to high-skilled manufacturing and the development of a domestic consumer society. By 2003, the OECD estimated that Ireland had the 4th highest GDP per capita in the world on purchasing power parity basis. Unit labour costs shot through the roof during this period, reducing Ireland’s competitiveness in export markets and leading to inflation that was usually above the EMU average. The departure of Dell, a large manufacturing employer, from Limerick to Poland was a signal that Ireland had lost its edge in low-end manufacturing. It is important governments and policymakers in emerging nations learn from Ireland’s mistakes.

Ireland will push through this crisis, but there are going to be some bumps along the way. And apart from analysing the state of the Irish economy in this letter, I’m also going to let you know what are “must-do’s” if you visit Ireland. Stay in a fishing village called Kinsale in County Cork. The Dingle Peninsula, Ring of Kerry and Aran Islands were also highlights on my week long journey. Have a few Guinness. Don’t have 10.

See you all soon,

Doyley

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

17 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox