Yesterday, Stefan and Mike gave a teleconference discussing our views on the eurozone debt crisis. They cover some very interesting issues, such as the relationship between current account deficits and sovereign defaults/crises, the ECB’s ‘underwhelming’ response to the current crisis and the implications for the financial sector of the strong link between sovereigns and banks, as well as what all this means for corporate bond markets.

There are moments where the quality of the recording suffers, but bear with it, because they are only brief.

We hope you’ll find it interesting and thought provoking and of course if you have any questions, feel free to comment below.

As we’ve stated earlier this year, we think the European high yield market is presenting us with some very interesting opportunities. As of 6th October, one of the high yield indices that we track had an average yield to maturity of 12.0%. This equates to a risk premium above and beyond government bonds of around 10.4%, a level that we believe more than compensates investors for expected default risk over the next few years. To put it bluntly, we think high yield bonds are cheap. However, this always begs the (very valid) rejoinder: “Sure it’s cheap, but can it get cheaper?”

The age old problem is that investors can be duped by optically cheap valuations only to lose money as the market continues to re-price lower. Timing, at the end of the day, is still a very important consideration. Unfortunately for investors, timing is also one of the hardest things to get right. The best that most humble fund mangers can hope for is that the valuation case is so compelling that the potential upside over the medium term can cushion or outweigh any timing errors in the short term.

It was with this in mind that I took a look at the last two market cycles within the European high yield market to investigate the potential medium term impact of any so-called timing errors. The results were intriguing.

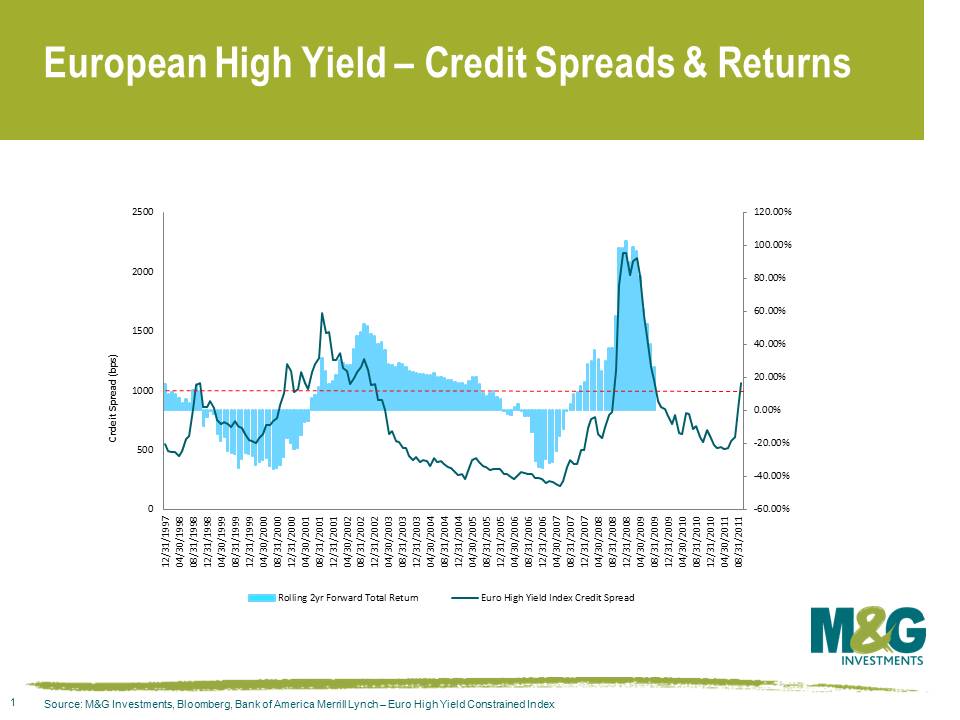

What the chart shows below is the credit spread of a Merrill Lynch High Yield Index on the left hand side (the additional yield above government bonds shown in 1,000th’s of a %). On the right hand side, the bars up and down show the rolling return over the next 2 years.

Focusing above the dotted red line, when credit spreads are over 10% (or when valuations suggest the market is cheap) the chart shows us that investing in the high yield market early in the TMT/Dot Com sell off of 2000/2001 would have led to negative returns over the next 2 years. Consequently, the chances of making a timing error were present early in the cycle despite the attractive valuations. The key reason, in my view, was the length and nature of the ensuing default cycle over the following 2 years. This was a fairly brutal default cycle, particularly for the telecommunications and cable sectors. Also, credit spreads remained elevated for quite a long time which denied investors the following wind of falling risk premia. Nevertheless, buying into the high yield market when spreads were over 10% would have generated attractive returns over the following 2 years roughly 75% of the time.

Contrast this to the post-Lehman sell off. Even though spreads peaked at far higher levels than 10%, the scope for making a “timing error” was literally zero using the same criteria. Total returns over the next 2 years were both consistently positive and high when credit spreads were over 10%. The key driver behind this is twofold. Firstly, the default cycle post-Lehman was fairly short and sharp and the sector with the highest default rate was banking & finance (not traditionally a large component of the high yield market). Secondly, the speed and scale of the market recovery meant total returns were particularly high in the following 2 years (rapidly falling credit spreads mean rapidly rising bond prices). Consequently, the lack of an extended default cycle coupled with a rapid recovery in risk premia generated some very high returns.

What does this mean for the European high yield market now we have crossed the Rubicon of 10% credit spreads once more? Are we set for a long drawn-out default cycle, or a short and rapid snap back in spreads that will swamp any timing error? I believe the answer lies in the nature of the next default cycle.

For what it’s worth here are my thoughts:

1) The default cycle will weigh most heavily upon sovereign issuers and banks (this is already happening).

2) I do not think we will see a rapid, sharp fall in risk premia to match the 2009 rally. Policy options this time around are more limited and fiscal constraints more acute.

3) There is some scope for a long drawn-out default cycle – but the risks will be concentrated in the European periphery (fiscal retrenchment and de-leveraging creates a hostile environment for highly leveraged companies exposed to these economies).

If I’m right, the next default cycle will present us with some clear cut opportunities and risks. The risk of “timing errors” is arguably highest within the financial sector and the European periphery. These areas could still present great opportunities in due course, but for now I’d argue that investors need to tread with caution. Go in too early and you run the risk of being swamped by a long drawn-out default cycle, despite optically attractive valuations.

On the other hand, the opportunities in European high yield away from these areas are plentiful. I believe the default cycle for the non-financial and non-peripheral issuers will be much more benign. Accordingly, the scope for so called “timing errors” is greatly diminished and this is where investors can cross the European High Yield Rubicon with much greater confidence.

Rating agency Moody’s today downgraded a swathe of UK banks. The reasoning behind this was not the weakening of the economy, nor the fact that, according to Mervyn King, we are in possibly the worst financial crisis ever. It was due to the changing nature of the blank cheque that banks receive from their implicit support from the state.

The rating agencies have recognised that government policy has shifted and that state support for banks is becoming limited and dependent on their systemic importance to the UK economy. This is not new news and the increasing risk that bank bond holders have been exposed to is something we have talked about before and has been illustrated painfully by recent price movements.

However, some interesting comments and pointers come out of the Moody’s press release. They not only assign higher ratings to some banks due to their size, but assign these higher ratings also due to their complexity ie “driven by large cross-border trading and derivative books”. This seems somewhat perverse for the state. Surely it does not want to be on the hook by providing more support to banks that threaten the domestic system due to cross border activities and complex derivative books, which the regulator has respectively less control over and less understanding of.

Going forward, the UK tripartite authorities (the Bank of England, the Financial Services Authority and the Treasury) are going to aim, through implementing policies along those recommended by the Independent Commission on Banking, to reduce this subsidy for too big to fail and too complex to fail banks. The eventual implementation of such policy would logically result in further downgrades of UK banks by the rating agencies.

The bank checks of the tripartite authorities mean fewer blank cheques. It appears under this scenario we still have further to go in the deteriorating credit quality of many UK banks as conferred upon them by the rating agencies.

On Tuesday we hosted a conference to discuss the longer term outlook for inflation. Our guest speakers were Adam Fergusson, the author of the brilliant book “When Money Dies” about the Weimar Germany hyper-inflation, Andrew Sentance, the famously hawkish former MPC member, and Ken Mulkearn, the editor of the Income Data Services Pay Report. Our very own Ben Lord also gave an update on developments in the linker and credit markets. Given yesterday’s Bank of England announcement of an additional £75 bn of QE, the discussions were pretty timely.

I did think about writing it up for the blog, but Andrew Oxlade of the Daily Mail has beaten me to it. Click here for his report. We did film the speakers, so we might be able to link to the video of the speeches shortly too.