The ECB’s bazooka has hit the target

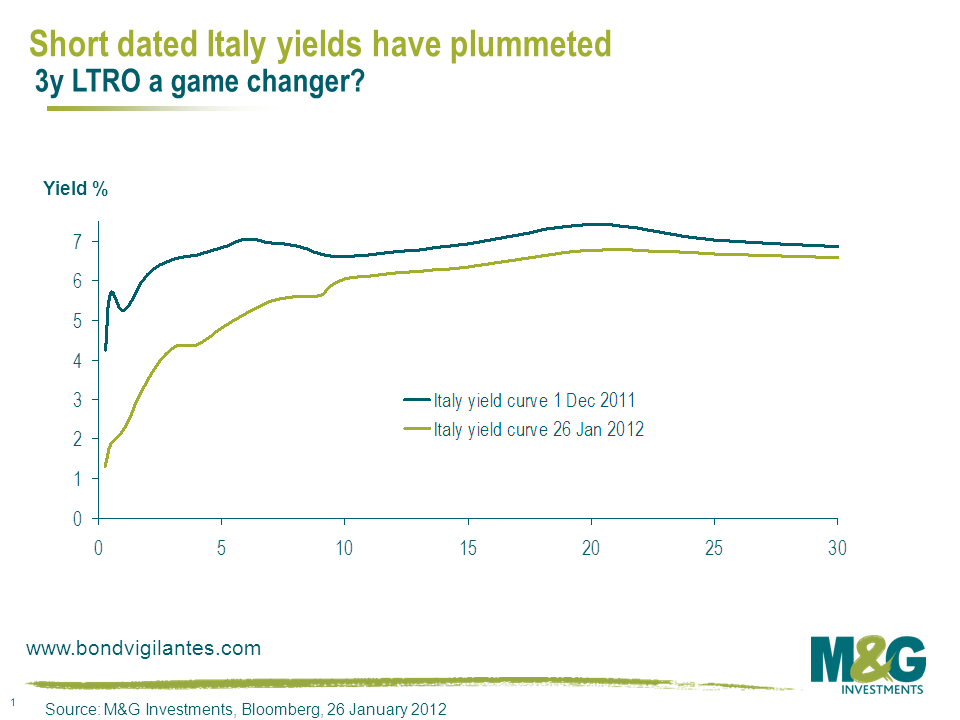

The ECB finally realised it had no choice and fired its bazooka in December. The impact has been huge. Two year Italian government bond yields have more than halved from the high of 7.5% seen at the end of November. Many hedge funds who were betting on Italian government bonds selling off have either changed views and taken profits or have been stopped out of their positions as the market has gone against them. Real money investors have been returning to the Eurozone sovereign bond market after a long absence. Just as Italian bank bond yields spiralled upwards with the Italian sovereign, so they have plummeted down too, and banks have been able to issue bonds to the market again this year (albeit almost solely covered bonds or senior bonds so far). The chart below highlights just how much Italy’s borrowing costs have fallen.

Those who doubt the sustainability of the ECB’s policies are entirely correct when they argue that hurling liquidity at the Eurozone debt crisis does nothing to solve the structural problems at the heart of the Eurozone. If you put lipstick on a zombie sovereign or zombie bank, it’s still a zombie. The potentially terminal problems of huge competitiveness divergence between countries (ie current account imbalances) are still to be resolved. One answer is total fiscal union, which requires Northern Europe to take on Southern Europe’s debts and Southern Europe to let Northern Europe tell it what to do (exceptionally unlikely). Alternatively, it requires Germany and the Netherlands to be willing to run consistently higher inflation rates than the rest of Europe (also unlikely). As Milton Friedman succinctly pointed out in 1999 (see Q&A session), “the various countries in the euro are not a natural currency trading group. They are not a currency area. There is very little mobility of people among the countries. They have extensive controls and regulations and rules, and so they need some kind of an adjustment mechanism to adjust to asynchronous shocks—and the floating exchange rate gave them one. They have no mechanism now”.

But just because the ECB’s policy response hasn’t addressed the underlying problems, it doesn’t mean the response is immaterial. Quite the opposite. We know from 2009 how powerful the effect on markets can be when central banks fully deploy their balance sheets. In light of this, the rally in the riskier fixed income assets that we’ve seen of late arguably has further to go, and in the past few weeks I’ve even bought Italian government bonds for the first time ever.

The flip side is that the current yield levels of core government bonds is a concern, and duration appears less attractive. In May last year, government bond yields were more than 1% higher than they are today and yield curves were much steeper. It was expensive to be short duration at the time, as argued here. The situation has changed a bit since then, presumably because of Eurozone stress and perhaps also because of China. If Europe is no longer in a downward spiral (indeed the crucial Eurozone PMI data released this morning suggests there has been a bounce in economic activity in January) then government bonds really do look vulnerable.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

17 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox