Peripheral Europe is still facing a debt crisis, despite appearances

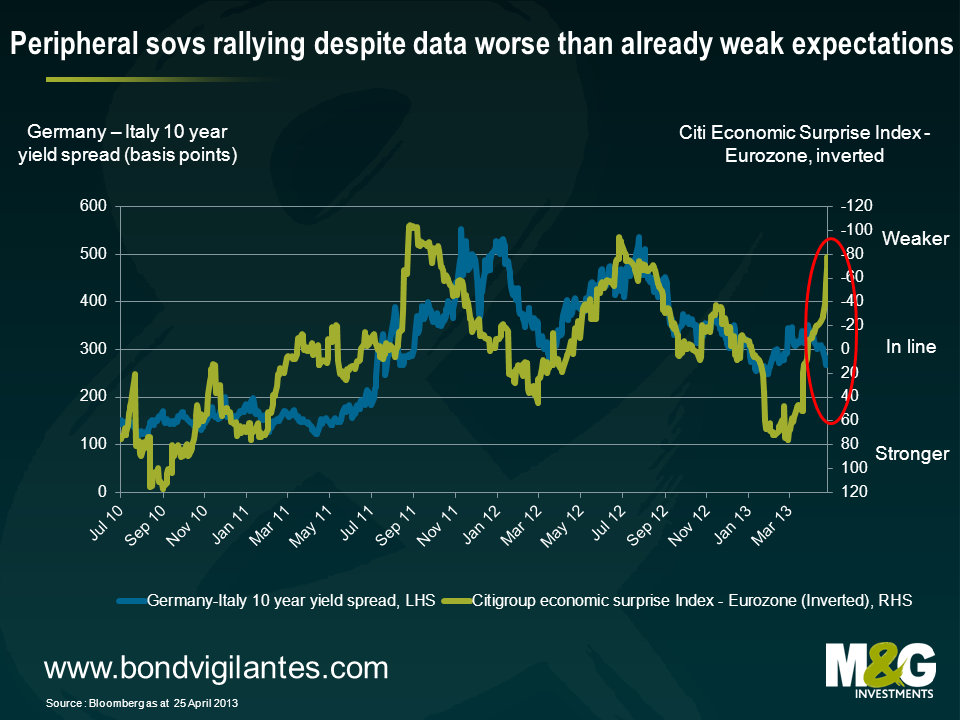

Earlier this week, 5 and 10 year Spanish yields fell to the lowest levels since Q4 2010. The rally was no doubt kick started by Mario Draghi’s “do whatever it takes to preserve the euro” comment, and was given further fuel by the improvement in Eurozone economic data over the latter half of 2012, which was probably due in part to Draghi. However, the peripheral rally has continued this year in the face of a significant deterioration in economic data in recent months. Economic fundamentals and valuations are currently moving rapidly in opposite directions.

The chart below illustrates this – on the left axis is the Italian 10 year yield spread over Germany, and on the right axis is Citi’s Eurozone Economic Surprise Index (so if the green line moves up, data is coming in weaker than expectation).

I continue to doubt whether Spain in particular is solvent, where I’d define insolvency as being where a country’s public debt/GDP ratio increases indefinitely. Yes, the ECB can throw liquidity at Spain to keep the debts rolling over, and yes, many other developed countries are arguably in the same boat – Japan’s public debt/GDP ratio is quickly rising towards 300%, which makes Spain’s public debt burden look relatively puny. But as we’ve seen with Greece, sovereign Eurozone debt can and will be restructured when a country is deemed insolvent, and as previously argued in a comment in 2010, this is where Spain appears to be heading.

Focusing on Spanish long term debt dynamics, it’s worth recapping that the change in a country’s government debt/GDP ratio is a function of three variables, namely:

- The difference between debt interest costs and nominal growth as a % of GDP. If interest costs are greater than nominal GDP, then this leads to a higher public debt/GDP ratio

- The change in a country’s primary balance as a % of GDP (where a primary balance is the budget balance before interest payments). A larger budget deficit equals a higher public debt/GDP ratio

- Changes in the stock-flow adjustment. This adjustment usually relatively small, but if a government recapitalises a bank, the public debt/GDP ratio increases (see here for more information)

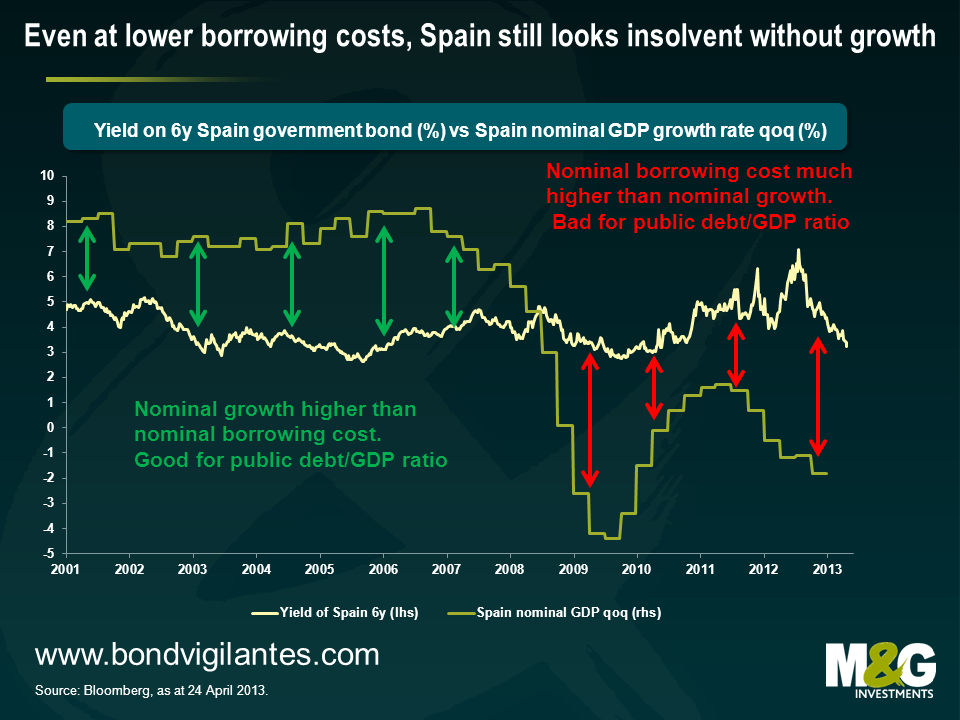

Spain’s public debt/GDP ratio has been soaring because of all three of the above variables. Taking each of these variables in turn, the chart below plots Spain’s nominal GDP growth against its 6 year nominal borrowing cost (strictly speaking it should be the average interest cost that goes into the formula, which for Spain is currently about 4% – I’ve taken the yield on Spain’s 6 year maturity as a proxy). A borrowing cost of 4% was fine from 2001 to 2007, as Spain was able to generate nominal GDP growth of between 7 and 9%. It’s not so fine now.

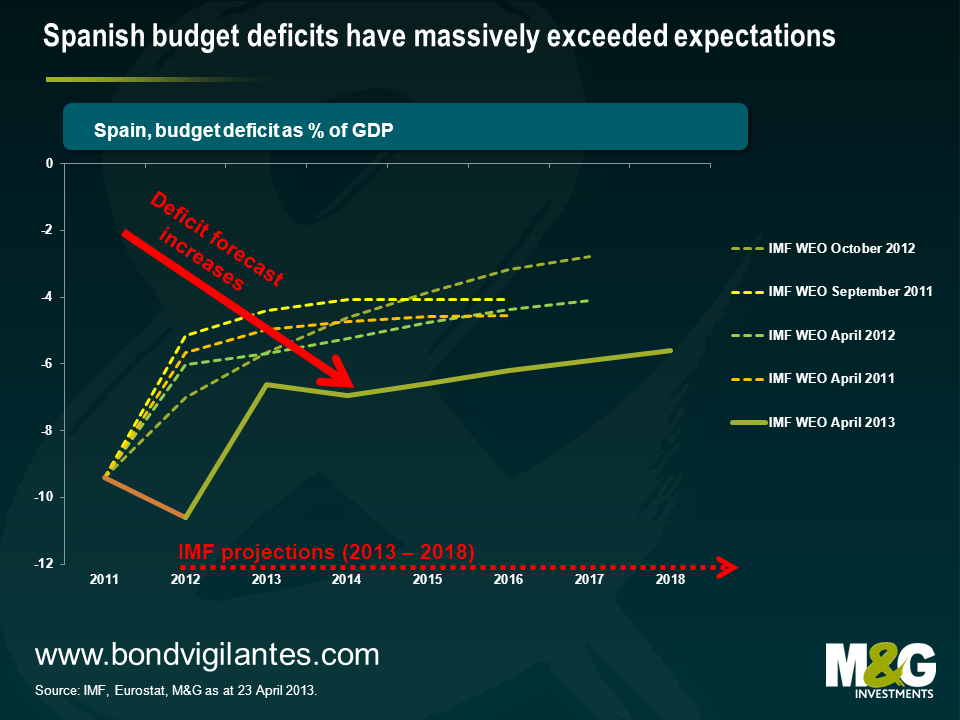

Given that Spain’s borrowing costs are higher than its nominal growth rate, it needs to run a primary surplus if it is to stabilise its public debt/GDP ratio (as per point 2). But Spain is actually running a huge budget deficit (averaging 10.2% since 2009), and is therefore running a large primary deficit. The chart below shows how the IMF has steadily increased its forecast for Spain’s budget deficits since 2011.

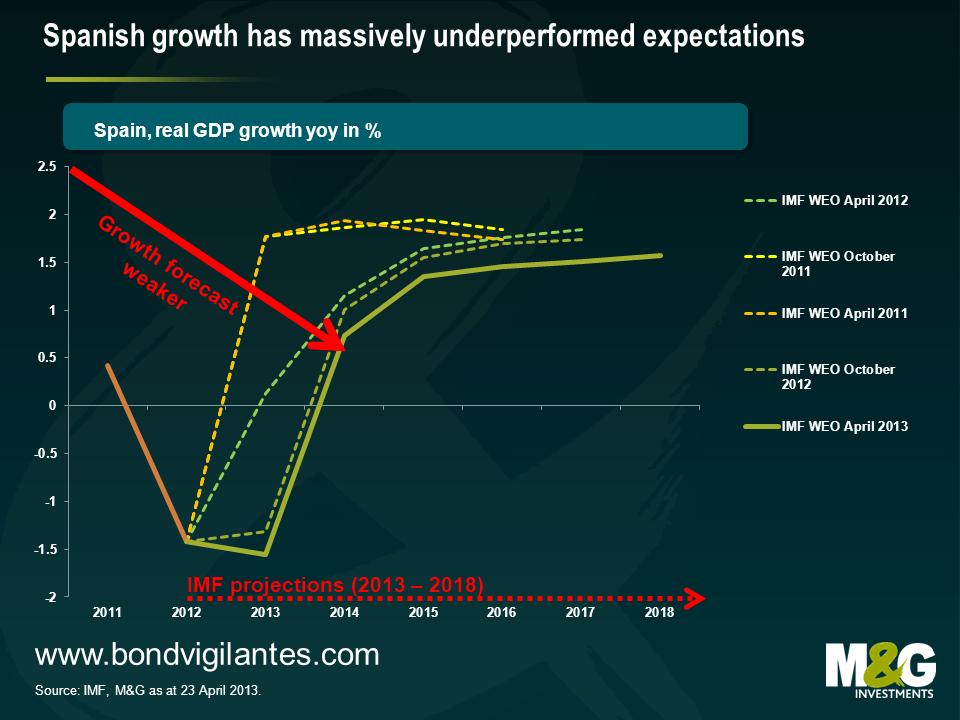

Part of the reason why the IMF has forecast larger and larger deficits is down to its growth forecasts being hopelessly optimistic. The chart below shows how in 2011, the IMF thought Spain would be growing at a tidy 2% by now, when instead Spain remains mired in a slump (yesterday it was announced that the unemployment rate hit a record 27.2% in Q1). Most forecasters’ long term growth estimates are simply countries’ long run historical averages, but given Spain’s high private and public debt levels, as well as deteriorating demographics, Spain’s long run potential growth rate may be as little as +1% per annum.

What about the third point about the debt/GDP ratio, namely stock flow adjustments? Our Spanish banks analyst Ed Felstead believes it isn’t inconceivable that even some of the banks that have been recapitalised by the state will need additional recapitalisations, despite the transfer of their most toxic real estate developer loans and assets to Sareb, Spain’s ‘bad bank’. Non Performing Loan (NPL) ratios at the now ‘clean’ banks remain high and revenue generation remains low on falling margins. Any further deterioration in asset quality on non-real estate developer loans will result in the banks having to take more provisions, which will lead to losses, with no way to replace the lost capital. This deterioration is likely given the state of the Spanish economy mentioned above, along with Sareb asset sales putting pressure on asset prices, and potential new borrower-friendly legislation on foreclosures and arrears.

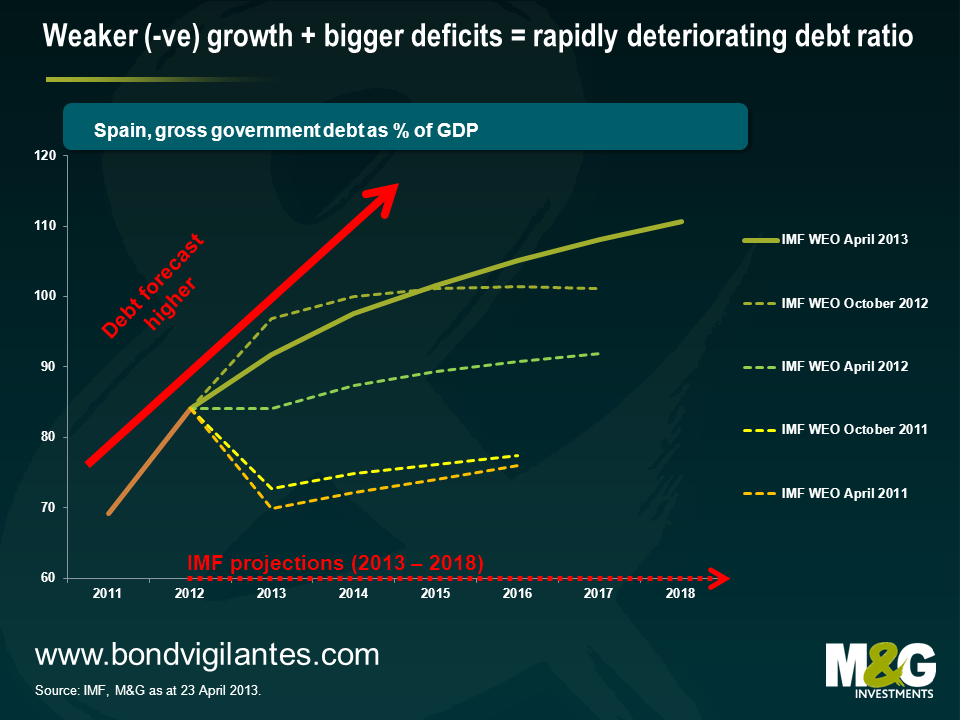

So in the absence of a miraculous return to growth, Spain’s borrowing costs will continue to exceed its growth rate, large budget deficits will remain a feature, and it’s easy to see how further bank recapitalisations will be necessary. The IMF is no longer forecasting that Spanish debt levels will level off but will continue rising for the foreseeable future, and that’s even with what appears to be over-optimistic mean reverting GDP growth assumptions. Peripheral Eurozone bonds, and Spain’s in particular, look vulnerable to a sell off.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

17 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox