The US unemployment report: challenging the payroll consensus

The US unemployment report for April highlighted the continuation of the economic recovery. The market is now in the habit of viewing a job creation number of anything less than 200,000 as a weak result for the labour market and anything more than 300,000 as a strong result. Anything in between and the conclusion amongst economists is this: the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) is on hold, economic growth is reasonable, inflation is not a concern, and interest rate increases are not imminent.

To me this seems a bit complacent.

As the unemployment rate falls the US economy will get closer to the point where the low supply of labour will cause wages to increase. Inflation will get an upward push, and the FOMC will likely feel like it has to remove some of its ultra-loose monetary policy by raising interest rates. In the theoretical extreme, were we to get to full employment, then focusing on the absolute payroll jobs number does not make sense. By definition, at full employment very few jobs can be created, as there is no spare labour. An employment report of 100,000 or less when the US economy is operating at full capacity would indicate a vibrant economy with inflationary pressures.

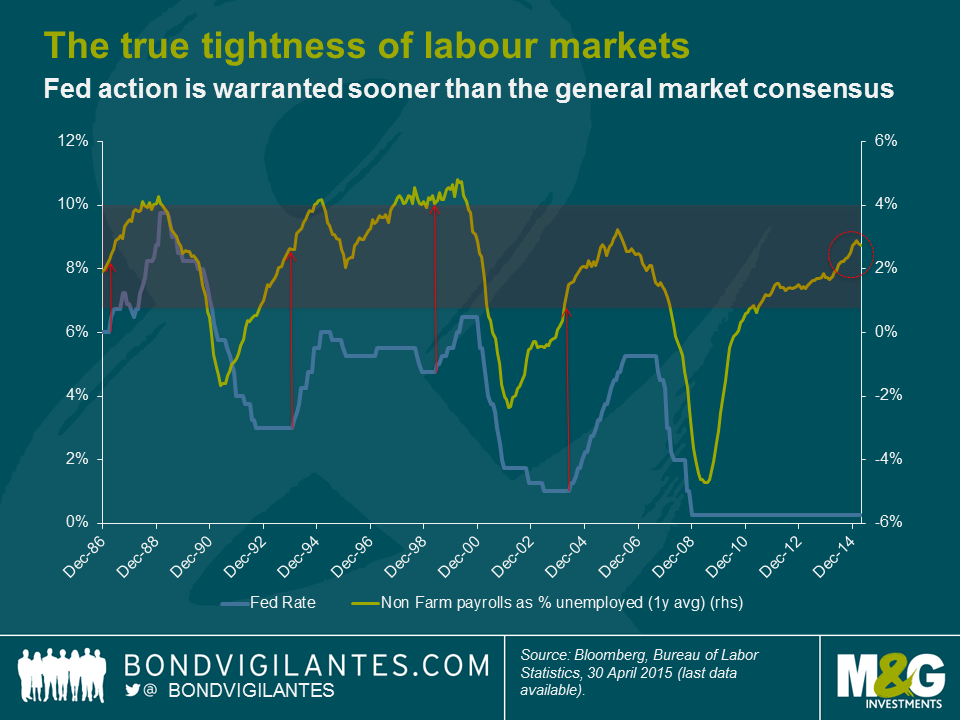

In order to analyse the labour markets as they approach full capacity we have created the chart below. The chart shows the ratio of jobs created as a percentage of the spare labour available. This is an attempt to move the focus away from a headline payroll number, to the true tightness of labour markets.

As can be seen, labour markets by this measure are historically very tight, and I therefore think wage pressures are stronger than the market consensus. Pre-emptive FOMC action is warranted sooner than the market is currently expecting (Eurodollar 90 day futures are pricing in a rate hike in December). Plotted alongside historic fed rates, we can see how far the normal FOMC interest rate response is to the labour market data in this cycle. Historically, when non-farm payrolls as a percentage of those unemployed has been this tight (around 2% level), the FOMC has begun a tightening cycle (in 1986, 1993, 1999).

In economics it is easy to focus on the absolute number, however one should always delve beneath this to analyse the relative. Given the strength in the US economy I would not be surprised to see higher wage growth numbers, rising inflationary pressures, and FOMC action despite the non-farm payroll number staying well behaved in absolute terms. At some point, strong job creation and low unemployment rates will result in higher compensation, and this would not be taken well by the bond markets.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

17 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox