Are the European Commission and the IMF right about Italy?

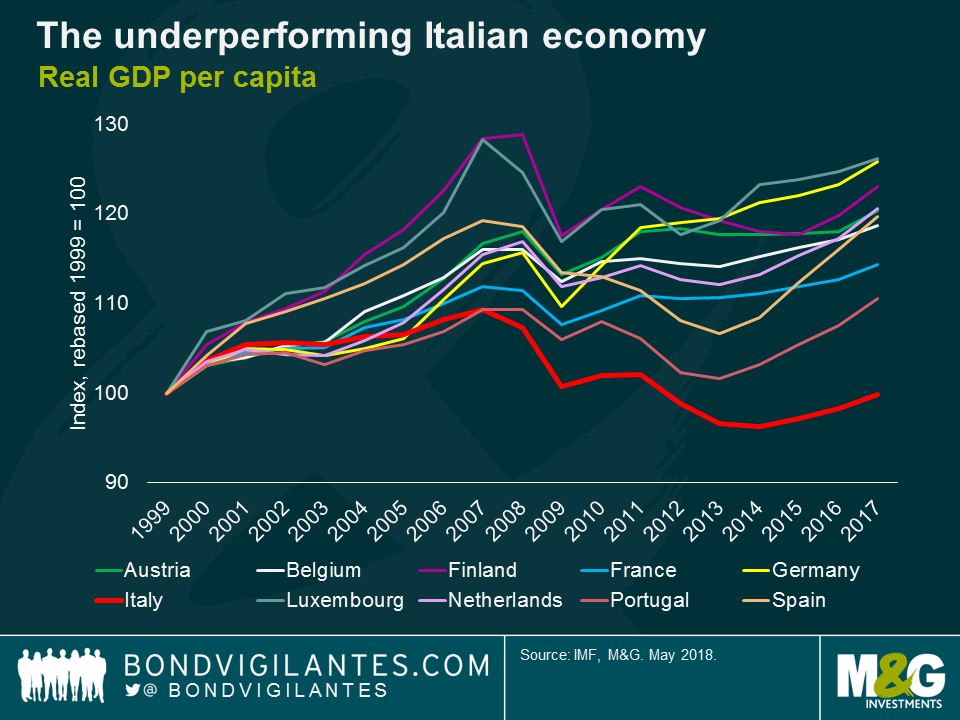

Persistent structural weaknesses, imbalances, and financial fragilities. These were some of the ways in which the International Monetary Fund (IMF) described the Italian economy in its most recent country report. Almost a decade after the great financial crisis, Italy’s economic prospects remain dim, with the costs borne disproportionately by the working age and younger population. With no government in place, a deeply divided electorate has complicated the prospects for much needed reforms and adjustments. Real disposable incomes per capita are below pre-euro accession levels, while Italy’s euro area partners are likely to pull even further ahead in terms of GDP per capita growth and incomes in the coming decade.

Italy’s economy is the third largest in the euro area, accounting for 16% of the area’s GDP. Because of its size, the EU Commission has already warned markets that Italy’s economy is potentially a major source of economic and financial risk for the euro area. The Public debt-to-GDP levels are around 133 percent, the second highest in the European Union (EU) behind Greece. Non-performing loans of banks are around 21 percent of GDP, amongst the highest in the EU. With ultra-easy monetary policy providing ample liquidity to prevent a short-term crisis, the European Central Bank (ECB) and President Mario Draghi have been able to prevent a scenario of a member nation leaving the single currency bloc.

Longer term, there remain significant issues with the Italian economy that will have to be addressed in order to withstand a tougher economic environment. Given the structural weaknesses that exist in the Italian economy (like high unit labour costs, high taxation, barriers to competition, an inefficient public sector), will Italy ask to leave the Economic and Monetary Union of the European Union (EMU)?

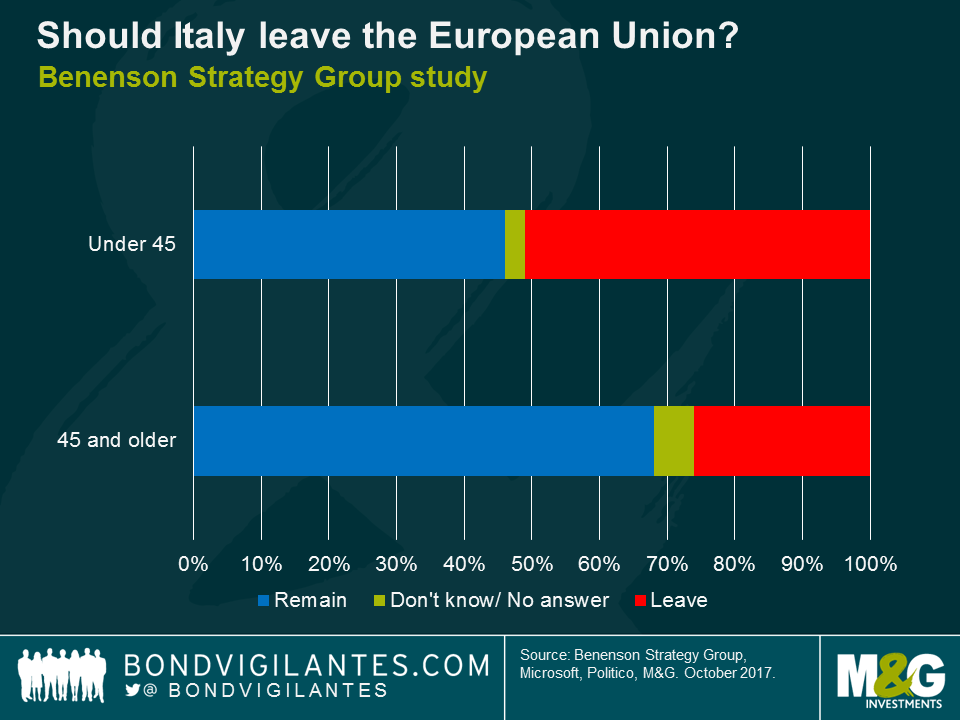

Given the political and economic backdrop, it is unsurprising that recent survey results suggested that if Italy were to hold a referendum on EU membership, 51 percent of voters under 45 would vote to leave, while 46 percent would vote to remain (voters aged over 45 supported staying in the EU by 68 percent to 26 percent). Younger Italian voters are unhappy with the EU, believing that economic convergence amongst EU member nations has come at the expense of Italy. However, with nearly half the Italian population over 45, the young of voting age are vastly outnumbered, suggesting the probability of Italy triggering Article 50 is low.

Would Italy be better off outside the EU and the EMU? Unlikely. An EMU exit by a member state would likely result in capital outflows and bank runs, leaving the banking system in ruins. A devaluation of the new currency would instantly result in high inflation and sharply cut wages. There would be a huge number of legal ramifications on a range of complex issues, not least the validity and enforceability of outstanding re-denominated contracts and obligations with creditors. It is for these reasons and many more that several Greek governments have turned away from Grexit in in favour of bailout programmes.

The outlook for the Italian economy is not particularly bright within the EMU, with soft economic growth forecast by the IMF over the medium term. Italy also faces the prospect of a decade or more of painful internal devaluation. For example, it is estimated that Italian nominal wages should be devalued by 20%, and more than 30% in manufacturing, to regain competitiveness with Germany. In the absence of a Greek-style internal devaluation, it appears that Italy will continue to muddle through, but the lack of Government is preventing the country from implementing the necessary changes for the economy to overcome its structural issues.

For bond investors, the lack of structural reform, high debt-to-GDP levels, the slow withdrawal of quantitative easing and a potential regime change at the ECB (which will be led by a new President from November 2019) suggests caution is warranted when lending to Italy at longer maturities. A 10-year spread of 119 basis points over Germany is below the 5 year average of 159 basis points, suggesting some discounting of the challenges the Italian economy faces. In addition, Italian yields are distorted by quantitative easing and the ECB is estimated to own 28 percent of Italian government bonds. Their current low spread over Bunds is also symptomatic of a market reaching for yield, encouraged by low yields in “core” European government bond markets. On a relative basis, BBB-rated Italian 10 year bonds are trading wider than their major EMU partners, including those located on the periphery that were responsible for the Eurozone debt crisis.

The current favourable macroeconomic and monetary environment will not continue indefinitely. It is important that the authorities in Italy and Europe acknowledge the IMF’s warnings in order to address the fragilities that exist within the Italian economy. If not, one may wonder if Italy could become the source of another European economic crisis.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

17 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox