Market sentiment turned risk-off last week, largely due to the new US sanctions on Russia, which destabilised the ruble, and with the worsening of the situation in Turkey, which sank the lira and hit European lenders to the country. What are these two crises telling us about the state of the global economy? Watch some insights from M&G fund manager Wolfgang Bauer.

Renewed political tensions between the US and Turkey and Russia increased uncertainty and led to a currency sell-off in both countries. Traditional safe-haven assets, such as US Treasuries and the yen, rose. Are these crises telling us anything about the state of the global economy?

What is happening and why?

The Turkish lira and the Russian ruble plunged recently, following an escalation of diplomatic tensions between the two countries and the US. In the case of Turkey, problems escalated after a deadline for Turkey to release a US pastor lapsed earlier this week. And on Friday, US President Trump authorised the doubling of some metals tariffs on Turkey. In Russia’s case, the US has proposed new sanctions amid the country’s alleged involvement in US elections. The Turkish lira fell to an all-time low against the US dollar, while the ruble reached its lowest level since March 2016. The tension around Turkey escalated on Friday after Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan said his country wouldn’t bow to economic warfare.

Which assets were more reactive?

Markets turned into a risk-off mode, with investors flocking to traditional safe-haven assets: the world benchmark 10-year US Treasury yield fell to 2.87%, after surpassing 3% only last week, and even despite core inflation posted its biggest gain since 2008. The US dollar and the yen rallied. Most European sovereign yields also fell – except those of Spain, Italy, Portugal and Greece. Emerging Markets (EMs) and their currencies dropped, especially those with a fragile political or economic situation: the argentine peso fell 3.3% against the dollar on Friday, while the South African rand lost 2.5%. European lenders to Turkey were also hit, as a lower currency hinders the payment capacity of Turkish borrowers. Spreads of Italian and Spanish banks’ contingent convertible bonds widened.

What could happen now?

Investors expect Turkey to act quickly to contain the currency drop, as the depreciation makes Turkey’s foreign bill more expensive, especially as the country imports most of its oil needs. Turkey seems to have two ways forward:

- Orthodox: Rate hikes to contain the lira’s fall. Other measures could include Fiscal consolidation and an improvement of the country’s relations with the West in order to ease the US sanctions. This could potentially facilitate an aid programme from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). In this scenario, Turkish banks and companies would suffer, but the pain could be spread over two years. Under a recession, Turkey may see its spending and debt increasing, but assuming its sovereign debt were to increase from 30 to 50% of GDP, this might not be disastrous. Money would have to be spent on bailouts for corporates and banks. Turkish corporate debt is 70% of GDP, of which 35% is in hard currency. Of this 35%, around half is loaned from Turkish banks – which might have to be nationalised under a worst-case scenario. The main threat to companies could be the lack of external funding rather than a fall in growth/recession. Erdogan has been attempting to diversify Turkey’s funding sources and trading partners, courting Russia, China and Qatar. A US $3.6bn loan was recently secured from China, but that is only a small part of Turkey’s $240bn funding needs.

- Unorthodox: Implementation of capital controls. This could spread the crisis to European banks with significant exposure to Turkish debt. This solution, as we saw in Argentina, could be more unpopular, as people would be forced to trade in local currency only.

Are these crises telling us anything about the state of the global economy?

People often say that turbulences such as these are warnings that bigger crises are ahead. But Turkey has been challenged for some time and Russia seems to have enough buffers to absorb the potential new sanctions, as long as oil prices don’t collapse. Russia has always been heavily oil price-dependent. In terms of global growth, China, the US, Europe and Japan have a much bigger influence, and these economies, although far from being at full traction, are still growing at a healthy pace.

Is there any danger of contagion to other EMs or Developed Markets?

Contagion is always a threat and recent events could heighten volatility. However, and over the long term, countries and assets are largely driven by their own fundamentals. As ever, thorough analysis and selection is paramount before making any investment.

Despite a battery of central bank meetings, which left things more or less where they were – read: supportive of economic growth – global bond markets suffered from the ongoing trade wars, from rising oil prices and also as US data remained unconvincing, dragging down inflation expectations. Only about one quarter of the 100 fixed income asset classes followed by Panoramic Weekly posted positive returns over the past 5 trading days, mostly led by US High Yield (HY), which benefited from a strong earnings season and its traditional domestic focus. The asset class shrugged off US President Trump’s renewed threats to impose higher tariffs on Chinese imports, a move that continued to drag the renminbi lower, until China made it more expensive for investors to short its currency, partially containing the drop.

The renewed tensions lifted the US dollar, hitting Emerging Markets (EMs) and their currencies, especially those of countries that export to China, such as Chile, a leading copper producer. US foreign policy also impacted other nations, such as Russia, whose currency plunged 3.6% against the dollar after a group of US senators introduced new sanctions amid the country’s alleged interfering in US elections. Other EMs suffered on their own account: The Turkish lira sank 7% against the greenback and its 10-year sovereign yield spiked to 18% as, adding to recent political upheaval, the central bank said it will not meet its 5% inflation target for three more years. Some EMs fared better: Mexican government bonds were the five-day top-performing asset class, out of 100, up 1.5% and taking their 1-month return to 4%. Investors are favouring bonos on hopes that a new North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) will be reached soon.

Sterling plunged almost 2% against the dollar, reaching a one-year low, on concerns the country will not strike a deal with the European Union (EU) to have an orderly exit next year. Despite Prime Minister Theresa May’s recent diplomatic efforts in the French president’s holiday villa, speculation is that Brussels-centred officials will have as much say in the final decision as Europe’s heads of state. She may have to swap the Cote d’Azur for Brussels next time.

Heading up:

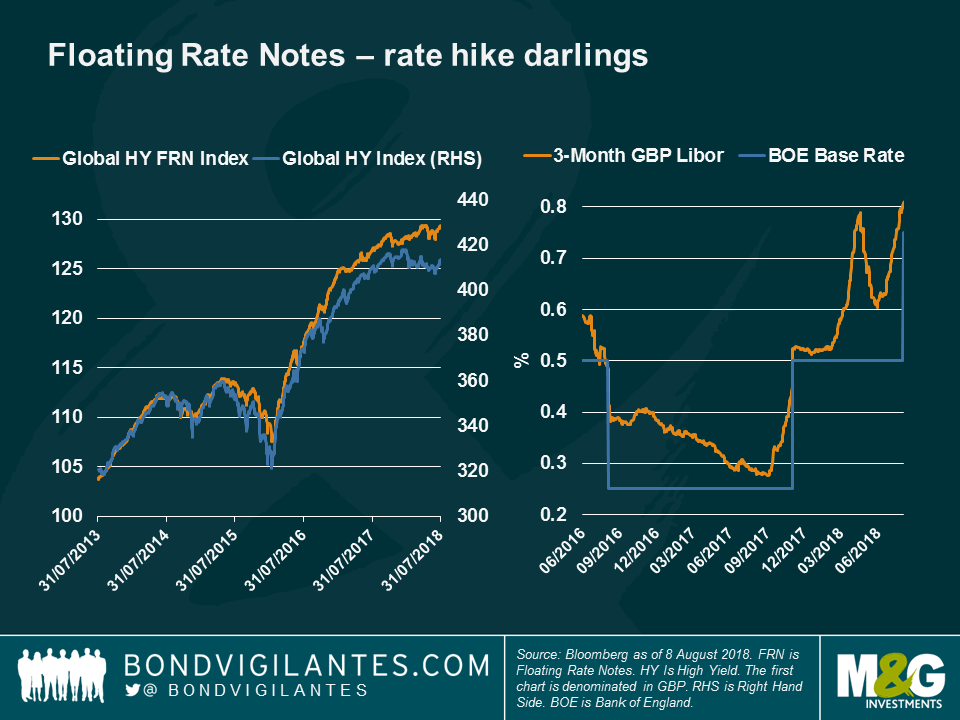

High Yield Floating Rate Notes (FRNs) – going for a hike? After years of trailing behind, HY FRN’s have now caught up and surpassed their fixed-interest paying HY pals: so far this year, Global HY FRNs have returned 1.3% to investors, compared with the 0.1% drop offered by Global High Yield names (both denominated in sterling). As seen on the chart, the decoupling between the two intensified towards the end of last year, when more central banks, other than the US Federal Reserve (Fed), started signalling that future rate hikes were on the table: the European Central Bank (ECB) unveiled plans to rein in its monetary stimulus, while the Bank of Japan (BOJ) has slightly widened the target trading range for the 10-year sovereign yield. FRNs are popular in a rising rate environment as their coupon is linked to a rate benchmark, such as Libor, which tends to shadow the central bank’s base rate. As seen on the chart, GBP-Libor rose following the Bank of England’s rate hike last week. Because coupons are reset periodically to match Libor, FRNs also have lower interest rate risk, reducing potential price losses when interest rates rise. A bigger coupon is also more likely to absorb any price drop derived from rising rates. To learn more about FRNs and the consequences of the BOE’s latest hike, watch M&G fund manager Matthew Russell’s recent video and read his blog.

Trump’s enemies – booming exports: Despite Trump’s loud and direct attempts to reduce the US trade deficit with leading exporters such as Germany and China, the fact is that the two countries’ exports continue to boom: Chinese exports rose at an annualised 6% in July, more than expected, while imports surged 21%, also more than forecasted. At the same time, Germany’s Current Account surplus rose for a third consecutive quarter, reaching 8.1% of Gross Domestic Product, one of the highest in the world. Germany and China’s export resilience raises questions about the true effect of the new US tariffs, which have so far hit China’s currency and the EM asset class, in general.

Heading down:

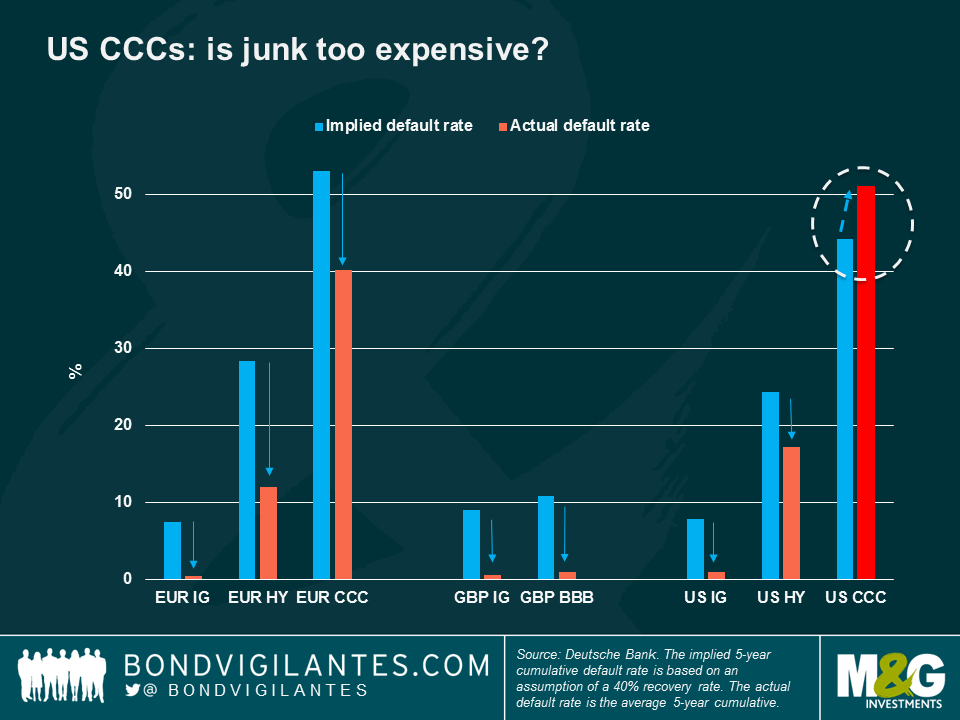

US CCCs – paying for junk: The lowest rated HY category has outperformed other HY rating brackets so far this year, as yield-hungry investors bought into the asset class encouraged by an improving US economy, a relentlessly increasing stock market and rising corporate profits – perhaps paying less attention to the usual red flags: Moody’s Investors Service defines Caa-rated debt as “very high credit risk, poor standing.” Still, investors have continued to buy the lowest US junk-rated debt, attracted by its high coupons, strong correlation to economic growth and traditional domestic focus, which makes it less exposed to international trade wars. The interest, however, has lifted valuations to a level that implies a 5-year cumulative default rate that is below the actual 5-year cumulative default rate: as seen on the chart, current prices imply that US CCC-rated bonds will default less than in the past. According to some market observers, such optimism is backed by a strong US economy; according to others, such positive view is unfounded, especially as US data has failed to show full traction; hence, they favour other, more pessimistically-priced asset classes, including some higher-rated HY brackets, as they offer higher credit quality and are also cheaper, on a relative basis. How much can investors pay for junk?

Italy – budget drama: Italian sovereign bonds lost almost 2% over the past five trading days, lifting the 10-year yield to 2.8%, the highest in Europe and about 1.5% above Spain’s. Investors have sold the country’s debt on concerns that the populist coalition government may increase spending in next month’s budget, widening its current 2.3% (of GDP) deficit. The country’s debt plunged after May, when some members of the ruling coalition questioned Italy’s presence in the Eurozone. Prime minister Giuseppe Conte reassured investors on Wednesday the budget will be serious and rigorous. Italian bond yields continued to rise.

Despite investor doubts about its prospects at the end of last year, the US stockmarket has led global equities so far in 2018. What could derail this momentum? And what are the potential effects of tariffs on US stocks? John Weavers, a fund manager in M&G’s equities team joins us to discuss what the impact might be and what could happen going forward to those exposed to China.

Few eyebrows were raised after the Bank of England raised rates: the last time unemployment was this low, the City of London was full of bowler hats – fund manager Matthew Russell says from the Bank of England.

Don´t miss Matthew´s blog: BofE – The unreliable boyfriend finally comes through with the chocolates

The Bank of England unanimously raised its benchmark interest rate by 25 basis points to 0.75% – are gilts still an attractive investment opportunity? Are rising rates the main challenge to UK government and corporate bonds? Has Brexit risk been priced in?

Is the Bank of England right to raise rates?

The unreliable boyfriend finally came through with the chocolates – after months of going back and forth, the Bank of England finally delivered what everybody had been expecting for months. The tightness of the labour market may have been the main reason behind all MPC members agreeing on the hike today – perhaps this tightening of the labour market is a bit beyond their comfort levels.

This hike shouldn’t raise any eyebrows: Unemployment is at its lowest since 1975, unit labour costs are on the rise, PMIs are looking healthy and inflation is above target. Increasing the rate 25bps seems entirely reasonable.

In a rising rate environment, are gilts still an attractive investment opportunity?

Rising yields make bond prices fall – but sometimes the cushion provided by the coupon that investors get is large enough to absorb the price loss, which means that investors still get a positive return. In the UK, this is a bit trickier because UK bonds typically have longer maturities relative to other developed markets: this means that investors are exposed to more interest rate risk (or duration). In this sense, short-duration debt may be more attractive in a rising rate environment. As shown in the chart, short-dated Investment Grade (IG) UK corporate bonds offer one of the biggest cushions to protect investors against rates moving higher: their yield needs to rise by almost another 1% before investors lose money.

Are there any other instruments that could help investors in a rising rate environment?

Floating Rate Notes (FRNs) are another option. Like any other bond, their price will be negatively affected if rates rise, but their coupon will adapt to interest rate moves, so it will increase if rates do, helping hedge some of the risk.

Higher rates are not the only threat to UK bonds – how about Brexit? Is the risk priced in?

As seen on the chart, UK IG spreads have moved more in synchrony with US dollar or Euro-denominated corporate debt, which reflects global investors’ risk appetite and global macro concerns more than any Brexit issues.

This happens because:

- The UK IG index is not necessarily a reflection of the UK economy as the index is as internationalised as the FTSE 100, which derives c. 70% of revenues from abroad. For example, the largest issuer of the UK IG index is EDF, a French company, which accounts for c. 2.5% of the index. Of the top 10 issuers, only Heathrow has all of its infrastructure within the UK.

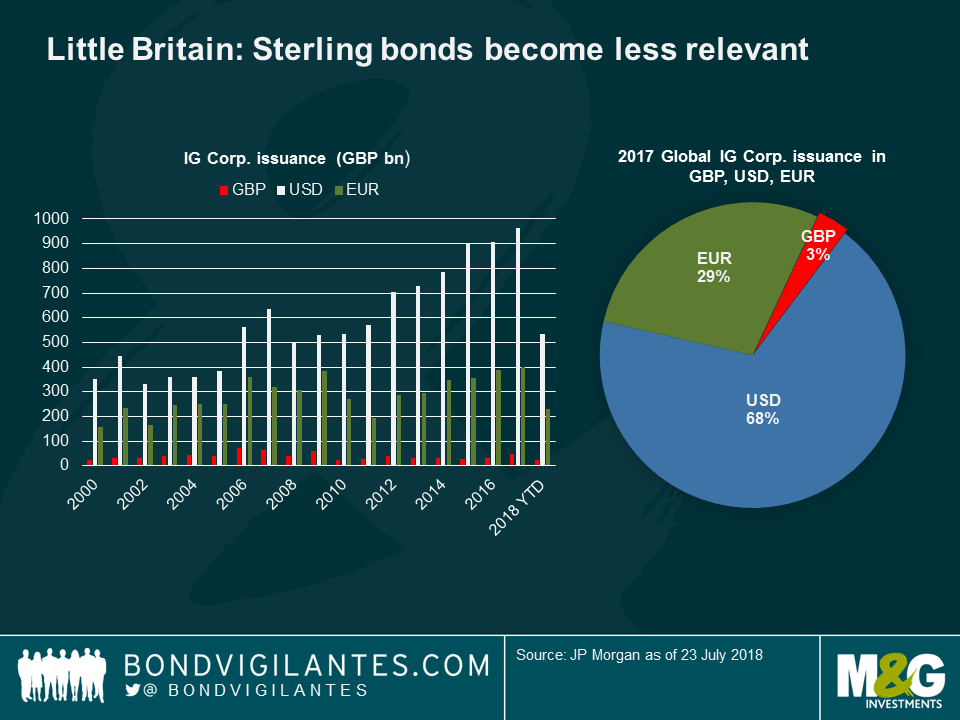

- UK companies have issued debt in other currencies, such as US dollars and euros. This would include leading issuers, such as banks, including HSBC, a major issuer. As for Britain’s small and middle-sized companies, they tend to use more bank debt or other private sources rather than financial markets. The High Yield market, which is widely used by smaller companies in the US, is also relatively small in the UK.

- Political uncertainty: At the moment it is hard to predict the final outcome of Brexit. UK politicians seem to disagree on many aspects of the deal, which in any case will also have to be negotiated with the EU. We are still a far way off any certainty.

- Credit is a bottom-up creature: In the corporate world spreads reflect company fundamentals. In the US we saw how higher tariffs led Harley Davidson to announce moving some of its manufacturing facilities outside the US – they are doing the best for investors. Sterling issuers, such as big banks (which account for about one quarter of the index), are already considering doing the same, so in this sense, spreads would not necessarily widen as profits wouldn’t be affected.

- The UK debt markets may not be as important as they have been in the past: The creation of the Eurozone and the globalisation of finance that we have seen over the past two decades means that Britain’s role in financial markets has diminished (see chart below). Also, given the tensions in the ongoing trade talks, international companies may be apprehensive about issuing in the UK.

The effect of Brexit on UK companies’ funding may come more through the banking system, as a weaker currency may lift inflation, pushing the central bank to increase interest rates. This would translate into higher borrowing costs for British companies.

Should UK investors look abroad?

Absolutely – diversification pays off, especially in delicate times. There is a big wide world in Fixed Income markets, much deeper and broader than what leading benchmark indices reflect.

Interested in a weekly summary of global bond markets? Don’t miss the Bond Vigilantes’ new’ “Panoramic Weekly,” published every Thursday. Read today’s: EMs 1 – Trump 0

Don´t miss Matthew´s video: Bank of England – is it right to raise rates?

Despite US president Trump’s plans to build walls between countries and impose barriers to global trade, the asset class which was once seen as the most vulnerable to his policies not only has emerged victorious in July – but also since he won in Nov. 2016: Emerging Markets (EM) fill 9 of the 10 best-performing fixed income asset classes in July, as their improving fundamentals and recent sell-off have made some valuations attractive, luring investors back into the asset class. EMs are also among the top performers since Trump won the election in November 2016: Mexican government bonds have returned 21% since, the 2nd-best rank among a group of 100 fixed income asset classes tracked by Panoramic Weekly. They only lag US Non-Agency Residential Mortgage-Backed Securities, which have gained on the back of improving US and global economic growth.

July’s general risk-on mode continued over the past five trading days as its sweet-spot conditions were bolstered: global trade tensions waned after the US and the Eurozone agreed to both reduce tariffs towards zero; US economic growth accelerated to 4.1% in the second quarter, the fastest pace since 2014, but sufficiently below expectations to keep the US dollar flat, and to quieten those calling for tighter US monetary policy; the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of Japan (BofJ) also confirmed their supportive, easing programmes, underpinning traditional risk assets; and oil, a key and expensive import for many EMs, eased to US$67 per barrel, down from $70. On the other hand, European sovereign bonds suffered as Eurozone inflation accelerated to 2.1%, the fastest since 2012.

Heading up:

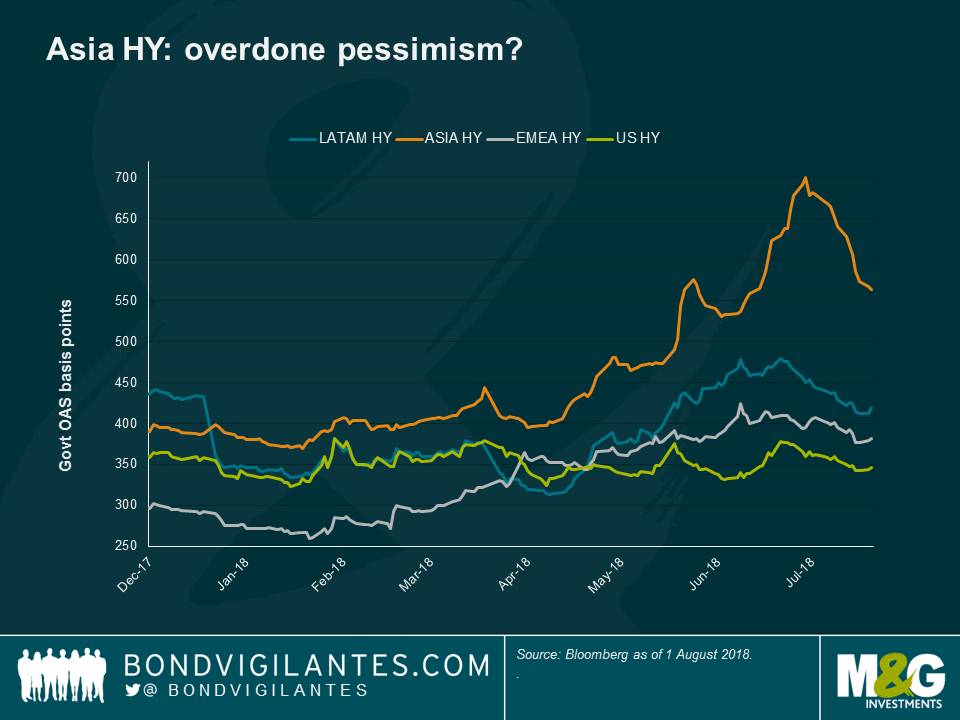

Asia HY – back with force: Asian HY bonds gained 1.6% over the past five trading days, enough to erase previous losses, bringing their 12-month return to a breakeven level. The asset class had widely sold off earlier this year, especially as the China-US trade tensions intensified, raising concerns that Chinese exporters, and their regional neighbour suppliers, would be hit by the new US tariffs on Chinese products. The tensions seemed to stall towards the end of July, especially after the US-EU trade agreement. US-dollar denominated Asian HY names were also supported by a new battery of Chinese fiscal measures, aimed at helping corporates at the same time that the government tries to rein in surging credit. The recent sell-off has also made some valuations attractive: the spreads of some Chinese property names reached as much as 800 basis points over Treasuries, a level that, according to some investors, had a total disconnect with their fundamentals – some provided double-digit returns in July. According to the World Bank, China has already overtaken the US as the world’s No. 1 economy on a purchasing power parity basis. Learn more about EM bonds’ performance and outlook in this Q&A with fund manager Claudia Calich.

Indian bonds – good hike: Locally-denominated Indian sovereign bond prices rose, despite the central bank’s increase in its benchmark interest rate by 25 basis points to 6.5%. At an annualised 5%, inflation is running above the bank’s 4% target. However, the central bank kept its neutral stance, relieving investors who feared that this year’s second hike would be the beginning of a tightening cycle. The move pushed down the sovereign 10-year yield to 7.7%, a three-month low, and strengthened the rupee to 68.4 units per US dollar, the strongest since June. Some investors, however, are still concerned about the country’s budget deficit, especially ahead of next year’s general election.

Heading down:

US Super Retail – choose your 501s: The risk premium that investors demand to hold US Super Retail bonds over Treasuries rose in July – while it narrowed for all the other 16 categories within the asset class. US Super Retail sector extended its three-month slump, hit by rising leases, online competition, continued mall traffic declines, and the difficulty of attracting screen-glued millennials. Shoppers of all ages continue to favour the ease of a mouse click over a trip to the shops, no matter how glamourous it might appear: some of the worst performing HY names in July included a high fashion store chain and women’s lingerie brands. More resilient were some well-established jeans makers, such as Levi Strauss – with a 1.5% excess return over Treasuries in July, its bonds seemed to be a better fit for investors. To learn more about the retail digital shift, read Stephen Wilson-Smith’s “Where have all the shops gone?”

Yen – yawn meeting: The yen was the worst-performing developed market currency against the US dollar over the past five trading days, dragged down by the central bank’s commitment to its ultra-loose monetary policy earlier this week. The move denied previous speculation that the bank would remove its present lid on 10-year yields, a move that would have most likely steepened the yield curve, helping bank profits and therefore improving the flow of credit into the economy. But none of this happened as inflation continues to be subdued; in fact, the Bank of Japan cut its inflation forecast for this year, 2019 and 2020. Investors will have to wait a bit more for some action.