Last night, the US Treasury designated China as a currency manipulator. This has occurred a few times in the past, most recently in 1994. Though China has been on the Treasury’s watch list for some time (alongside several other countries), given that the most recent Treasury report published in May did not name China a manipulator, it begs the question, what has changed between then and now?

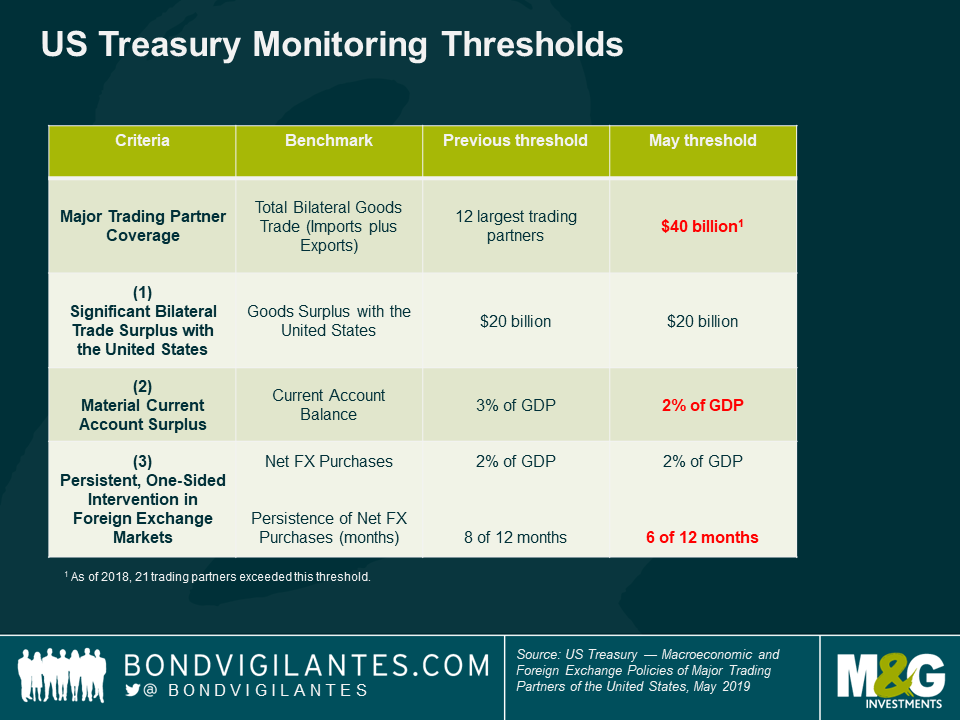

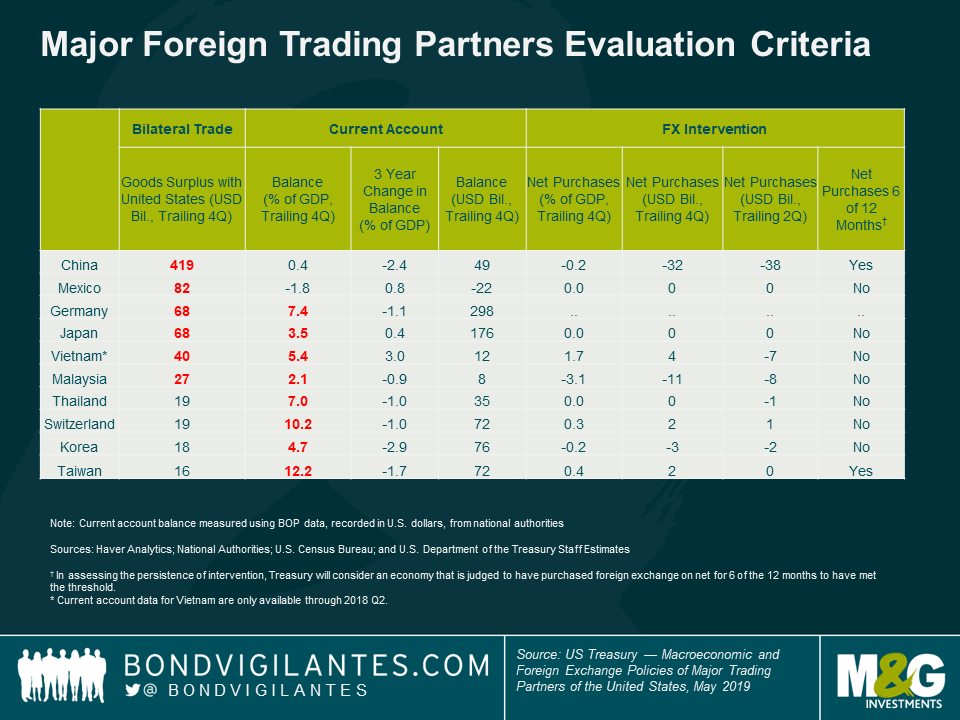

The criteria is based on the chart below. One of the issues with the criteria is that it focuses on the largest bilateral trade deficits in nominal terms. Arguably, this reduces the need to monitor bilateral imbalances for economies that are much smaller in size, where the surplus may be large (as a percentage of the economy) but small in nominal terms. One example is Israel, a small economy that posted a larger surplus, as a percentage of its GDP, than several other countries on the monitoring list (see our prior blog) This also means that a small open economy like Thailand would fall just below the $20 billion arbitrary threshold, but India, a larger closed economy would just exceed the threshold.

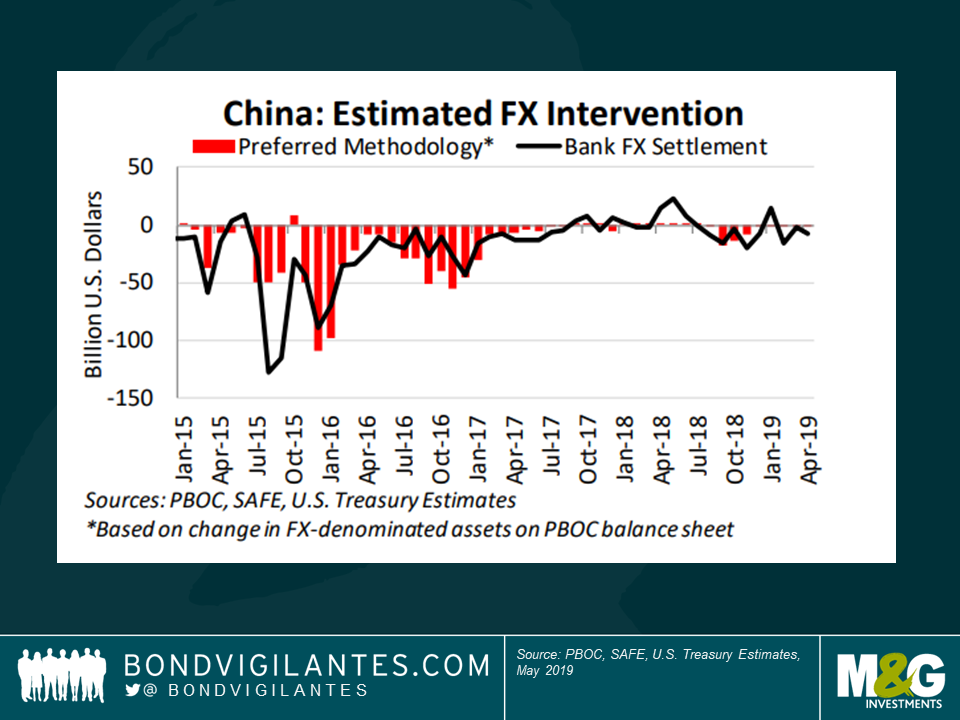

According to the Treasury’s most recent estimates below (China does not publish that data), China has not materially intervened in the currency for a large part of the last year. If anything, it was selling USD reserves to prevent a faster depreciation in 2015-2016, when it further tightened capital controls. Based on PBoC data, we do not believe it has materially intervened to weaken its currency since then. The Renminbi has however now crossed the 7 rubicon.

The US Treasury believes that China’s reserves are ‘above standard measures of reserve adequacy’. That may be true for a country that has capital controls, but as China aims to gradually open up its capital account, the level does not seem to be excessive. Reserves have been relatively stable since 2017 at $3.1 trillion, so the IMF’s calculations below are still valid.

From the criteria described above, it appears that nothing is likely to have changed since May, except that the trade war between both countries has intensified. China has been running large bilateral trade surpluses with the US for some time and the US allegations of protectionism and state subsidies are warranted, but nothing new.

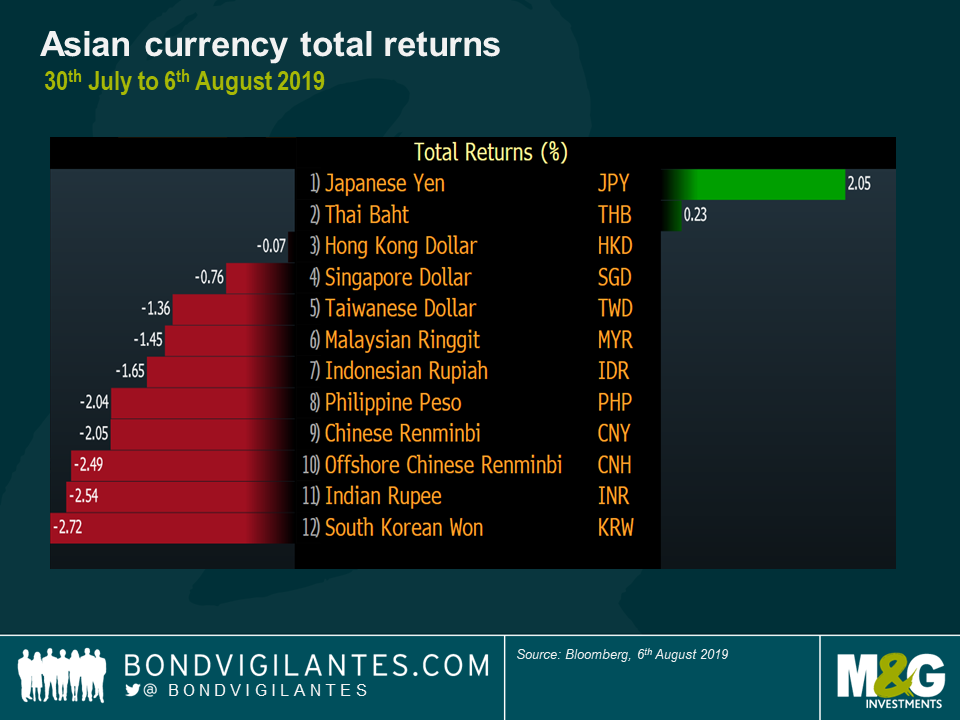

Following the recent US announcement that they will impose 10% tariffs on an additional $300 billion of Chinese goods, the PBoC allowed the Renminbi to depreciate past the closely-watched 7 level, but the depreciation was roughly in line with other Asian currencies. If anything, the Renminbi had, until recently, depreciated less than neighbouring currencies, which is something that the PBoC monitors closely when setting its daily fixing.

The bottom line? The data alone does not justify why China was designated a manipulator now, as opposed to May or October, when the next Treasury report is set to be published. The trade war continues to escalate and the timing is much more related to that, than what the data indicates. This is not over. Stay tuned.

Late on Friday night, the US announced a fresh round of sanctions against Russia, effective from the 26th August. These restrictions represent the 2nd round of sanctions in line with the Chemical and Biological Weapons Control and Warfare Elimination Act of 1991 (CBW Act). The announced sanctions include US opposition to the financial or technical assistance to Russia provided by international financial institutions, restrictions to exports of dual-use chemical and biological items and, most importantly: the prohibition of US financial institutions to participate in FX-denominated financing of the Russian government.

Shortly after the sanctions were announced, the US issued a clarification, stating that US financial institutions did not only include banks and brokers, but all US investors. Meanwhile, the definition of ‘Russian government’ includes the Ministry of Finance, Central Bank of Russia and National Welfare Fund – effectively excluding state-owned entities. Finally, the US Treasury explicitly specified that the new sanctions do not apply to RUB-denominated debt (OFZ) and secondary market trading of Russian government Eurobonds.

While the sanctions apply to US investors only, in practice Russia could be unable or unwilling to issue Eurobonds at all in the near future. UK and European investors are likely to shy away from any new issuance due to compliance concerns (or demand a significant premium for investing), while the demand from Asian investors remains very limited (they bought only 2-4% in this year’s earlier Eurobond issuance). The initial market reaction to the fresh sanctions has been surprisingly mild, which is unusual for an emerging market country. However, the Russian case is unique for a number of reasons.

Firstly, over the past couple of years Russia has successfully managed to largely shield its economy from the financial market volatility. It’s been an interesting case of prudent domestic economic policies, offsetting the negative impact of external politics. To start with, Russia has some of the strongest credit metrics across all emerging markets: general government debt remains around 15% of GDP, both current account and fiscal balance have been in surplus and international reserves have reached USD 520bn (it’s possible that the all-time high of USD 570bn in mid-2008 will be reached by year-end). Such reserve levels cover 17 months of the country’s imports and its outstanding external debt (both public and private) in full. In other words, if required, Russia could repay all of its external debt tomorrow and still be left with approx. USD 70bn of funds. Needless to say, this is very impressive by any market standards.

In this environment, the oil price is arguably the only variable that could rock the Russian economic boat. The country’s progress towards economic diversification has been very limited, with hydrocarbons still accounting for about 55% of goods’ exports and 25% of general government revenues. However, at current oil price levels Russia’s macroeconomic strengths are pretty comfortable: the federal budget is balanced at USD 40/bbl and according to the current fiscal rule, any extra revenues from higher prices are accumulated in the National Welfare Fund (which is likely to reach USD 120bn by year-end). The fiscal rule has also significantly weakened the link between the RUB exchange rate and oil prices, allowing the central bank to confidently steer inflation close to its 4% target.

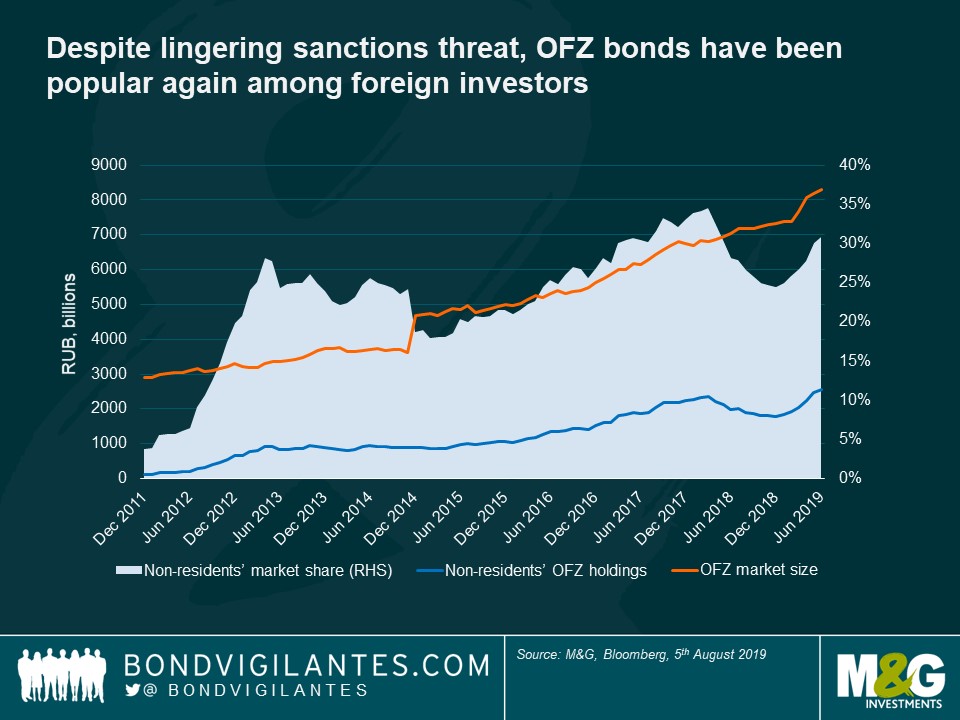

Secondly, the advance warning of sanctions makes a significant difference to the financial markets’ response. The 2nd round of sanctions in line with CBW and separate sanctions for new sovereign debt (including OFZ) have been discussed since autumn 2018. Investors who are not comfortable with taking Russian risk have therefore had plenty of time to sell their exposures – hence the very limited market reaction upon the current announcement. The ‘leavers’ have clearly been in the minority: Russian Eurobonds (JP Morgan EMBI) have still delivered a healthy total return of 12.7% year-to-date, while OFZ yields have compressed by 140 bp. According to a survey by Morgan Stanley in May, in the event of new sovereign debt sanctions, 46% of bond investors would have kept their Russian exposure unchanged, while another 20% would have added. In fact, the government issued a total of USD 6.3bn on the Eurobond market this year (twice exceeding the original plan), and up to 80-90% were bought by foreigners. This amount alone covers upcoming external maturities until September 2023. One should also keep in mind that of the approx. USD 42bn of Eurobonds outstanding, foreigners currently own only about 50%. With new OFZ issuance being explicitly excluded from the sanctions, the Russian government will be comfortable continuing these auctions, which have been very popular among foreign investors. Indeed, despite the sanctions threat lingering over OFZ since the autumn of 2018, its foreign ownership increased by USD 12bn year-to-date, reaching 30% (vs. an all-time high of 34% in March 2018).

In conclusion, the practical inability to issue Eurobonds in the near future matters little for the Russian economy and financial markets. Paradoxically, from a certain perspective, the long-awaited fresh US sanctions announcement may even be viewed as a positive, due to the nature of US internal politics. Since autumn 2018, there has been a lot of pressure on President Trump (mostly from the Democrats) to approve a separate legislation which would sanction all new Russian sovereign debt, including OFZ. The unexpected inclusion of new Eurobond issuance in the CBW sanction package clearly reduces the incentive from Congress to push for additional sanctions (which would include new OFZ issuance) and therefore provides a certain relief for financial markets, which had been pricing-in a significant risk of a more severe package.