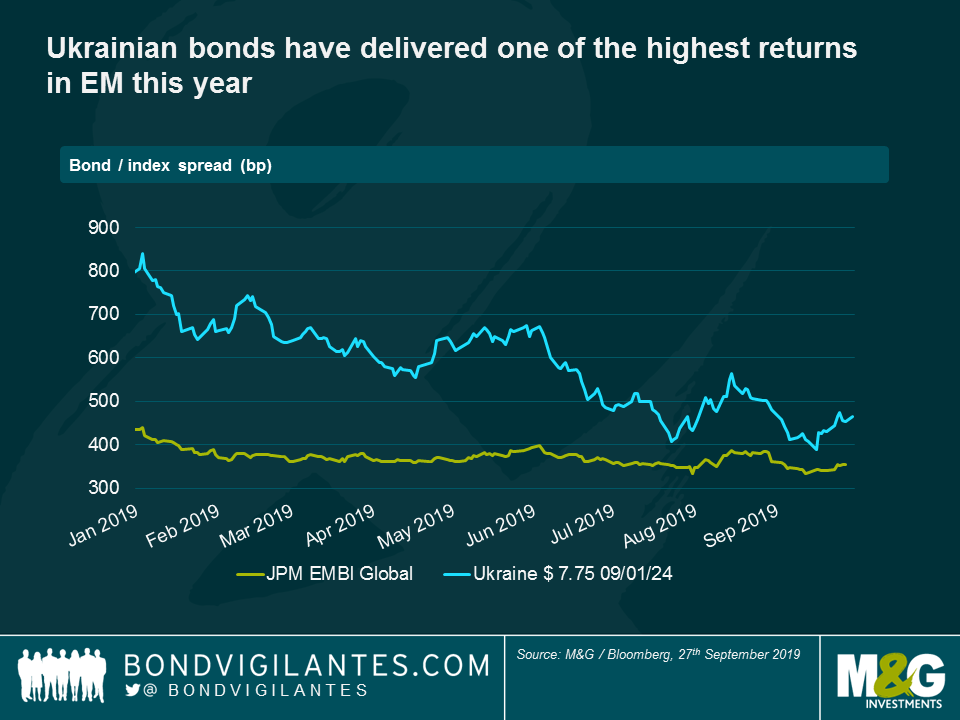

Ukrainian fixed income assets have performed better than expected this year, and delivered one of the highest returns in the emerging market universe. Since the beginning of 2019, Ukraine’s five-year USD bond spread has tightened by about 370bp, while the JP Morgan EMBI saw spread compression of just 70bp year to date. Political novice Volodymyr Zelenskiy and his Servant of the People (SP) party managed to achieve very convincing wins both in the presidential and parliamentary elections. The new market-friendly technocratic government has swiftly launched reforms and restarted negotiations with the IMF over a new financial support programme. Is the widespread market optimism warranted and likely to continue? Our view is yes, but with some important caveats.

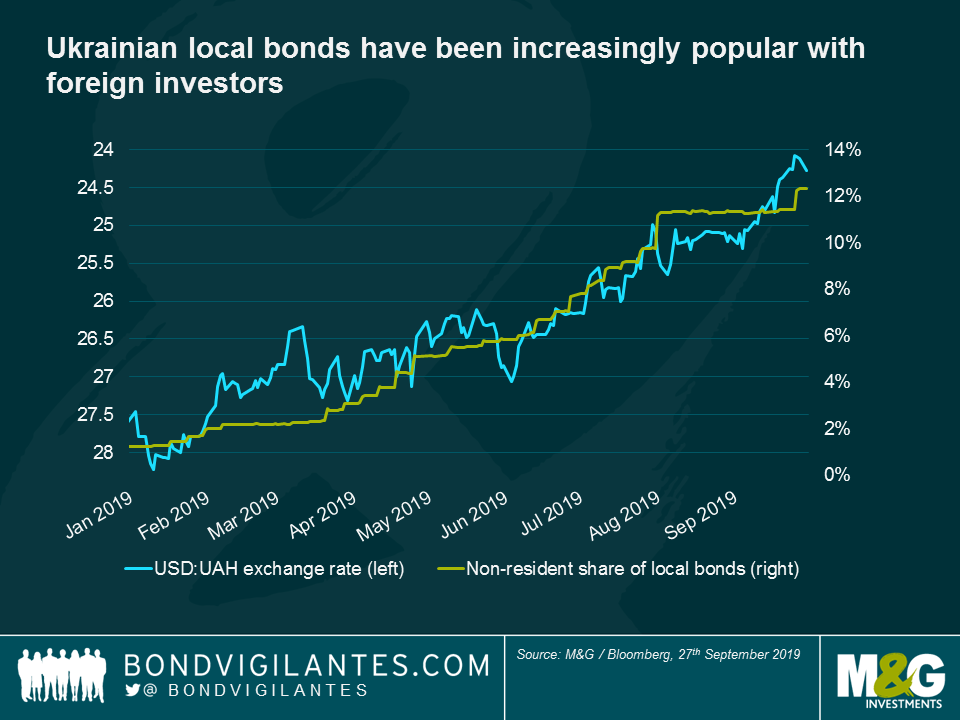

Macroeconomic indicators in Ukraine have improved significantly over the past couple of years. Tight fiscal policy has helped to contain budget deficits, allowing government debt (including guarantees) to drop to below 60% of GDP this year, down 20 percentage points from its 2016 peak. Growth has resumed, current account deficits have shrunk and international reserves have increased, while tight monetary policy has finally pushed inflation back into single digits. Foreign demand for local debt securities has been spectacular this year, boosting the share held by non-residents from 1% to 12%, and helping the UAH to appreciate by around 13% versus the USD. As stellar as this seems, there are reasons to believe there is room for further improvement.

The potential gains stemming from the implementation of various market reforms are huge. In particular, the government estimates that land reform (allowing the sale of land) alone could add as much as 3.5 percentage points per year to GDP growth and raise budget revenues starting from 2021. More conservative estimates from the private sector still point to an impact of 1-2 percentage points per year, representing a meaningful boost to the circa 3% growth the economy is currently enjoying.

Closing the judicial gap with neighbouring Poland just by half could add another 1 percentage point to growth over the next few years; there is further potential upside from a large-scale privatisation programme, new tax system and labour market reforms. Importantly, all of these reforms are not just wishful thinking with a vague implementation schedule. This was often the case previously. Now, while the new parliament and government assumed power only a month ago, the above-mentioned reforms are already being worked on actively with unprecedented speed. Indeed, the land reform bill was submitted to parliament last week.

Meanwhile, the IMF mission was in Kiev over the past couple of weeks, conducting talks with the government over a new three-year Extended Fund Facility programme of around $5-6 billion. While successful local market issuance this year has significantly reduced the urgency for Ukraine to receive the next tranche disbursement, the government understands the importance of IMF support and seems to be ready to comply with most (if not all) of the conditions attached. An agreement within the next month and a disbursement by year-end therefore remains the base case scenario. Provided an agreement is reached, other donors (including the World Bank and the EU) are also expected to contribute, increasing the total size of the external financing support to $10-12 billion.

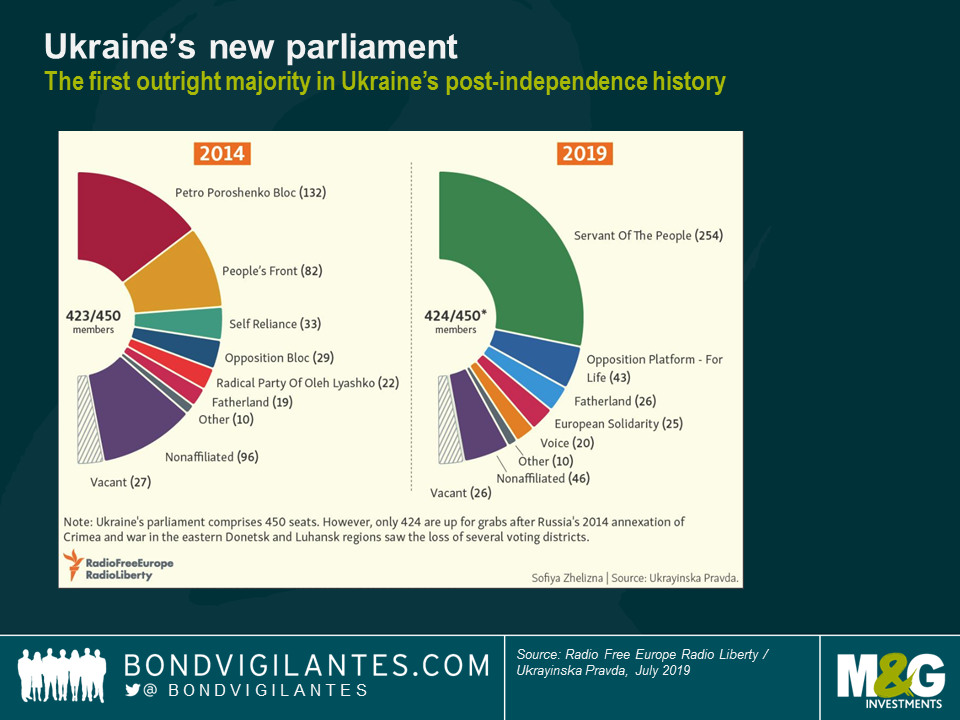

While macroeconomic risks have declined significantly, political risks are higher than they seem at first glance. In the July parliamentary elections, Zelenskiy’s Servant of the People (SP) party gained a solid majority in parliament, occupying 254 seats out of 450 in total. However, elected deputies from SP in fact represent a very diverse group of people: many joined the party only during the election campaign, and more than half (130) were elected from single-mandate districts, owing their victory almost entirely to the new president’s strong political image. The vast majority of SP deputies have no political experience, coming from all walks of life and often having differing views. Some local observers note already-emerging factions within SP that are becoming vulnerable to the influence of particular oligarchs whose interests are being undermined by bold reforms. The challenge of keeping the SP party together could increase with time: the government itself acknowledges the need to enact the most important reforms as soon as possible. More positively, a smaller, pro-reform party called Voice appears to be ready to support the government’s initiatives should the SP majority start to crumble. The problem is that Voice has only 20 deputies in parliament, so the potential for this support is rather limited.

Local analysts also note that further political risk may come from an excessive concentration of power in Zelenskiy’s team. Their full control over a largely inexperienced parliament gives the presidential administration a carte blanche to initiate all reforms and pass them rather quickly and without much debate. While such speed is commendable compared to the long delays in previous years, it can also lead to mistakes in the absence of proper checks and balances. A similar argument applies to the perceived desire to replace the majority of current civil servants in Ukraine, including judges, election commissions and potentially even central bank management. The pressure on the latter is of special concern to the IMF, for whom central bank independence is crucial to providing financial support. The unresolved case of Privatbank’s nationalisation could become another obstacle. The still-pending final court decision could do significant damage to the banking system in case the 2016 nationalisation decision is deemed unlawful. While the IMF might be willing to show flexibility regarding other issues (such as full liberalisation of the gas market by January 2020), any review of the terms of the Privatbank nationalisation could become a red line for the lender.

Regarding international politics, and on a positive note, under the new Ukrainian leadership there seems to be a higher chance of progress in resolving the ongoing conflict with Russia. One of Zelenskiy’s pre-election promises was to end the war in Eastern Ukraine, and a recent prisoners’ exchange between the two countries gives ground for some cautious optimism on this front. Though there are multiple obstacles and the full resolution of the conflict still seems far away, stability in Eastern Ukraine will be important to the government at a time of large-scale reforms.

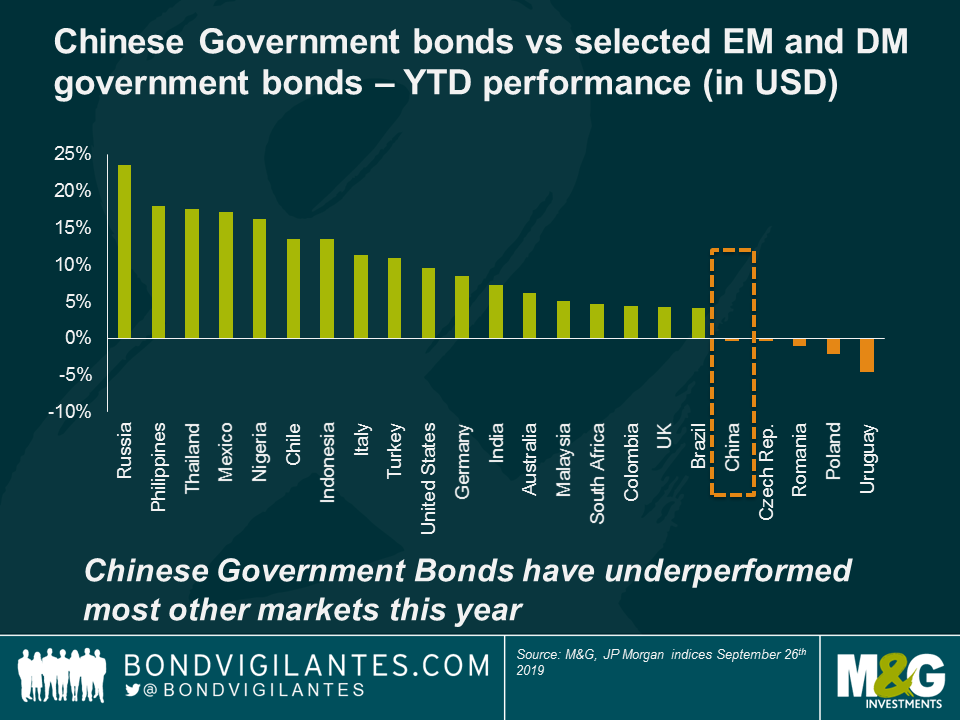

Yesterday evening, FTSE Russell announced that China Government Bonds (CGBs) would not be added to the widely followed FTSE World Government Bond Index, but remain on the watch list for inclusion until further review. This came as a surprise for most investors: Bloomberg Barclays and JP Morgan both recently added CGBs and bank policy bonds to their index suites. In challenging times for the Chinese economy, the delay means that Chinese bond markets will miss out on further inflows of billions of dollars from foreign investors. While in equity markets, China A shares have rebounded quite strongly after last year’s dismal returns, CGBs have posted disappointing results in 2019 (see chart below).

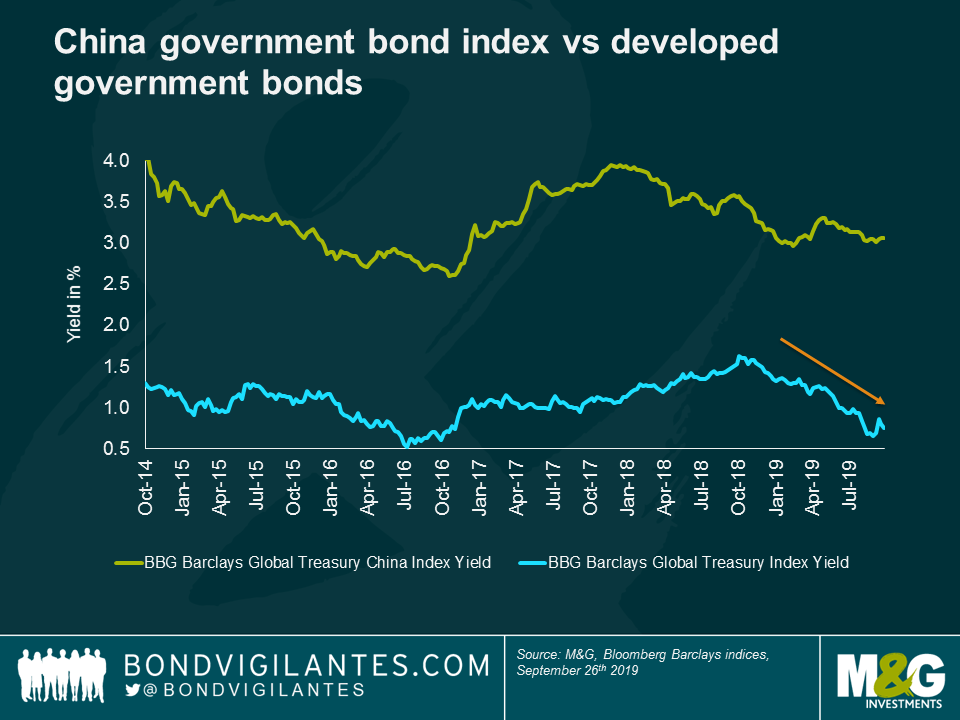

Following this underperformance, CGB yields now look quite attractive when compared to global developed government bonds. While CGBs are probably riskier overall, they represent an alternative source of income for investors in an increasingly yield-deprived world.

However, higher yields do not necessarily translate into higher future returns. With China’s trade dispute with the US still unresolved, the short-term outlook remains uncertain for CGBs. Should the economic situation deteriorate further, it will be interesting to see the reaction of China’s central bank, the PBOC. While many options remain on the table, there are a couple of more obvious levers that the central bank could pull.

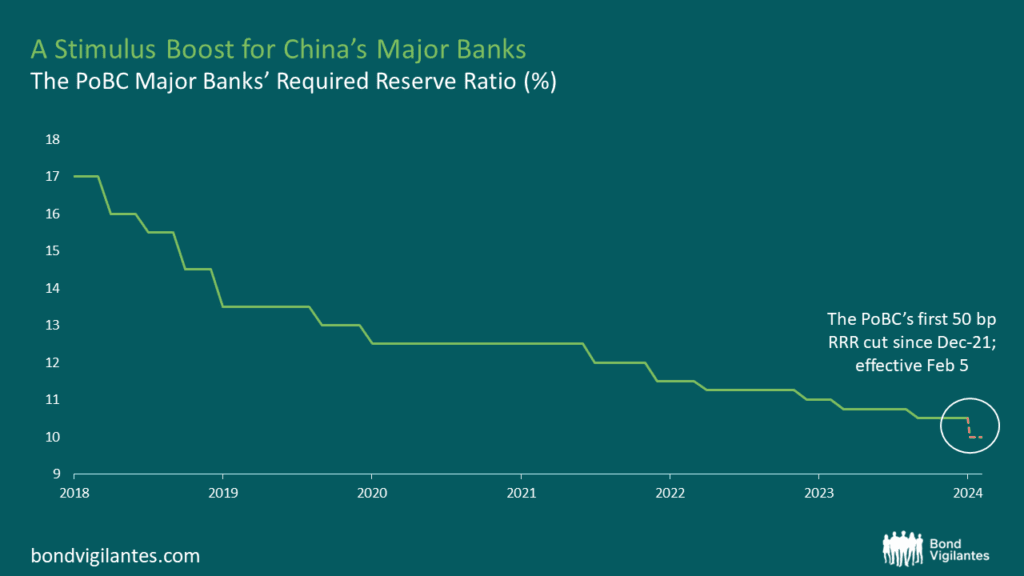

Firstly, the PBOC could reduce the Reserve Requirement Ratio (RRR), the amount of cash which banks must hold in reserves. This would free up liquidity for banks to make new loans to corporations and consumers. While the PBOC has already cut the RRR a few times since early 2018, there is still some scope to reduce it further. Based on historical movements, these further cuts would likely lead to lower CGB yields.

Another way in which the PBOC could loosen monetary policy is by cutting interest rates. Having evolved considerably over time, China’s monetary policy is still in a transition phase and the country has a variety of rates it could adjust to loosen monetary policy. These include the 7-day reverse repo rate as well as the medium-term lending facility, tools the PBOC has already used in the past. The recent changes made to the Loan Prime Rate also signal that this mechanism could be employed more extensively going forward. With average rates on loans still close to 6% in China, some measured monetary loosening could certainly be warranted. Reducing these key interest rates could serve as a catalyst to lower CGB yields in the future.

Of course, investing in CGBs does not come without risks. With 70% of all bonds held by local banks which often hold them to maturity, CGBs are less liquid than other, more mature bond markets and therefore tend to react less efficiently to changes in macro-economic, monetary and financial conditions. The difficulty in hedging positions using derivative instruments, as well as regulatory and fiscal uncertainties, present further obstacles for international investors. Finally, with a debt-to-GDP ratio in excess of 300%, China remains one of the most indebted countries in the world. Deleveraging will remain a significant challenge for the country over the long run.

Foreigners investing in CGBs will also be exposed to currency risks. While China’s government has pledged not to use the currency in retaliation to trade war escalation, in reality it has been the main adjustment valve to the ebbing and flowing of trade negotiations. Following President Trump’s recent round of tariff increases in early August, the PBOC let the currency weaken past the psychologically important point of 7 CNY per USD for the first time in over a decade. While it can be expected that the PBOC will intervene to prop up the currency should it start to devalue too quickly, a further contraction of economic activity would likely result in further CNY depreciation, especially against the world’s “safe haven” currencies. On the other hand, should a reprieve or stalemate be reached in the trade negotiations, one would expect the CNY to rally quite significantly given current valuations.

Where does this leave investors? Despite the decision from FTSE Russell and lackluster government bond performance since the beginning of the year, the financial integration of Chinese financial markets – while fraught with danger – remains well under way. Given this, and indeed the many challenges that the Chinese economy faces today, the inaction so far displayed by the PBOC could prove very valuable in the future, especially if the economic backdrop continues to deteriorate. Patience in this case could very well be a virtue.

All eyes are on central banks these days as major monetary policy decisions have been driving global bond markets. The eagerly awaited September meeting of the Governing Council of the European Central Bank (ECB) has given bond investors much food for thought. In particular, the new round of its asset purchase programme (APP)—announced in true ECB fashion revealing only the bare minimum of details—leaves plenty of room for speculation. So far, we only know that from November onwards net asset purchases are going to resume at a pace of EUR 20 billion per month for as long as deemed necessary to reinforce the accommodative impact of the ECB’s policy rates.

Credit investors like ourselves are naturally very interested in understanding the exact terms of the corporate bond element of the APP, i.e., the corporate sector purchase programme (CSPP). Here we try to provide answers to a few open questions.

How much corporate debt is the ECB going to buy per month?

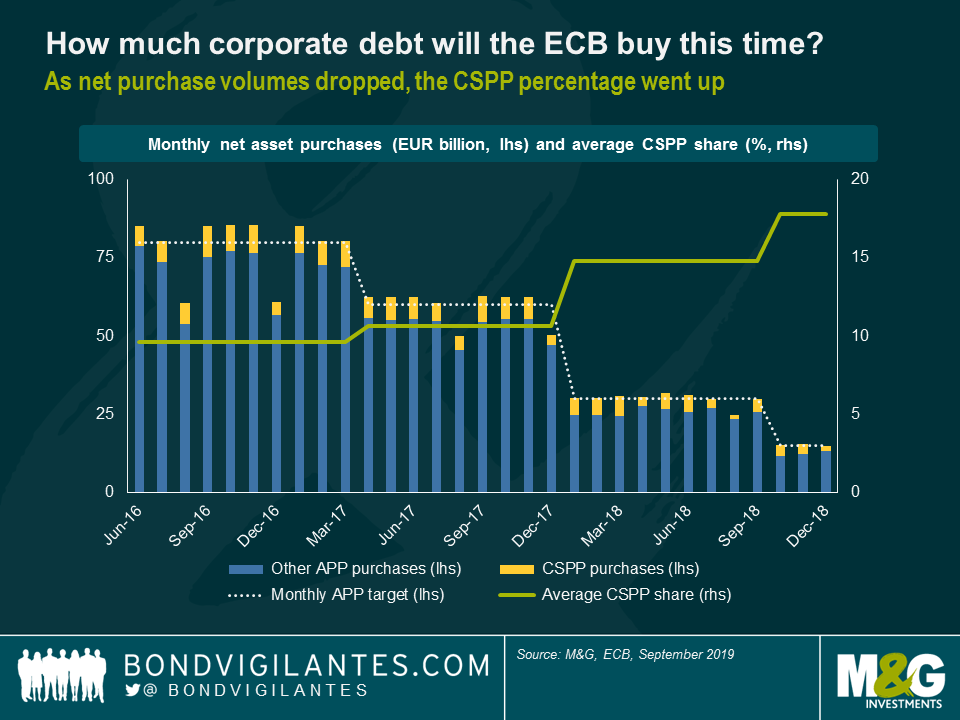

While the exact percentage of CSPP purchases within the upcoming APP round is unknown at this stage, historic data can help us define a realistic range of potential outcomes. It is important to note that the CSPP share has not been constant over time. Initially, when the ECB was buying EUR 80 billion of assets per month (until March 2017), CSPP purchases accounted on average for around 10% of all APP purchases. However, when overall monthly APP net purchase volumes were lowered first to EUR 60 billion (April to December 2017), then to EUR 30 billion (January to September 2018) and finally to EUR 15 billion (October to December 2018), the average CSPP share successively climbed up to around 18% in the end.

Applying the historic CSPP range of around 10% to 20% of all APP purchases, we can expect net purchases of corporate bonds to be anywhere between EUR 2 billion and EUR 4 billion per month from November onwards. My hunch—and it’s not much more than a hunch, I’m afraid—is that the ECB is going to push CSPP purchases towards the upper end of the range, i.e., between EUR 3 billion and EUR 4 billion per month.

Tilting APP net purchases toward the CSPP would effectively help the ECB buy time. The issue with public sector purchases, as opposed to private sector purchases, is that the capital key requires the ECB to purchase large quantities of German government bonds. Simultaneously, the maximum share of any public sector issuer’s outstanding securities that the ECB is allowed to hold is 33%. So, unless Germany abandons its balanced budget mantra (‘black zero’) and embraces fiscal expansion, thus increasing the Bund supply, the ECB will eventually run out of German government bonds to buy. As rules around the CSPP are less restrictive (capital key does not apply; 70% maximum issue share limit), it would make the ECB’s life a bit easier if a substantial share of net purchases was directed towards the private sector.

Are senior bank bonds going to be added to the ECB’s shopping list this time round?

Highly unlikely, in my view. Although Mario Draghi stayed fairly tight-lipped with regards to the finer details of the new APP round, he briefly noted that the types of APP-eligible assets would remain by and large the same as in the past, thus effectively ruling out the inclusion of bank debt. There had been rumours suggesting that the ECB might add senior bank bonds to the shopping list for the first time in an effort to cushion the blow to European banks’ profitability from further rate cuts. However, the distinctly bank-friendly aspects of the ECB’s most recent stimulus package—more favourable terms on targeted longer-term refinancing operations and the introduction of a two-tier system for reserve remuneration—have taken the wind out of the sails for this line of argument, I reckon.

Which parts of the corporate bond universe are likely to benefit the most?

Again, apart from Mario Draghi’s “expect more of the same” comment, we have very little information to work with. Assuming that the main CSPP eligibility criteria remain in place—euro denominated bonds, issued by non-bank corporations established in the euro area, with a remaining maturity between six months and 31 years and at least one investment grade (IG) credit rating—I would expect single-A rated bonds, French companies and the utilities sector to experience the strongest technical support under the new programme, just like under the old one.

Why did the ECB remove the yield floor for CSPP-eligible corporate bonds?

Interestingly, the ECB has flagged one rule change which is going to affect CSPP purchases. So far, purchases of assets with yields below the deposit facility rate (now -0.5%) were only permissible for public sector debt, but not for private sector debt. This time round, however, the yield floor is going to be abolished across all parts of the APP, including the CSPP. Hence, the ECB could buy corporate bonds yielding less than -0.5% from November onwards.

The actual impact of this rule change, at least in the current market environment, is unlikely to be material, though. In fact, apart from short-dated bonds issued by state-owned Deutsche Bahn, it is pretty hard to find corporate bonds with yields below -0.5%. This could change, of course, in case Bund yields take a leap lower at some point, thus dragging corporate bond yields down with them in the process. In this scenario, the yield on short-dated bonds from other highly rated issuers (such as Sanofi, Novartis or Total) might as well drop below the deposit rate.

In my view, the rule change is mainly of symbolic nature. It is a bullish signal telling credit investors that the ECB would be willing to support the high-quality end of the credit universe regardless of the prevailing yield environment.

Will European IG credit rally like in 2016/17?

No doubt, the fact that the ECB is going to buy once again large quantities of European IG corporate bonds is a material technical tailwind for the asset class, putting downward pressure on credit spreads and volatility alike. That being said, I wouldn’t necessarily expect a repetition of the extraordinarily strong credit bull market of 2016/17 for two reasons.

First, the scope of the new CSPP round is going to be more modest than in the past. Even if the ECB gravitates towards the upper end of its historic asset allocation range and directs a punchy 20% of net purchases towards corporate bonds, the absolute purchase volume of EUR 4 billion per month would still only be around half the amount invested in corporate debt on average each month between June 2016 and March 2017, when the original APP was in full swing.

Second, the entry point with regards to prevailing credit spread levels is less appealing. Before the ECB first announced CSPP in March 2016, investors had been spooked by the potential for a hard landing of the Chinese economy and a dramatic fall in the oil price. Consequently, the ICE BofAML EMU Corporate Excluding Banking Index—a rough proxy for the CSPP-eligible bond universe—was trading at an average asset-swap spread level of around 120 basis points (bps) back then. At this crisis-like level, credit spreads offered a lot of pent-up potential for an aggressive rally. Today, however, the index trades at a spread of only around 80 bps, which limits in my view the scope for further spread compression. I think a fair amount of ECB support is already baked into credit valuations at this point.

As the year of the 325th anniversary of the Bank of England’s foundation, and as the month of one of the Bank’s more important rate-setting decisions since 2008, September provides a congruous occasion on which to reflect on the history of the BoE and consider what the future holds for it. Founded in 1694 as a private bank to the government, it was in 1998 that the BoE was granted independence from the government in setting monetary policy. Now the UK faces perhaps its greatest political uncertainty in a generation, it is worth asking the question: to what extent will this independence continue?

We have already seen the effect of populist leaders on central banks that are ostensibly independent. The obvious case is that of the US, but there are other examples to be found of central banks facing political pressure to keep monetary policy easy, from Turkish President Erdogan’s sacking of the then central bank governor, to the ECB’s reaction to persistently low growth in Europe. Even if Trump doesn’t control the Fed directly, he certainly controls the market, which in turn has forced the hand of the central bank and led to the Fed cutting rates with the economy in expansion. And with ever more monetary sweets to choose from in the jar, which politician could resist raiding the cupboard and giving their economy a sugar high of rate cuts, QE and lending?

Pressure on the Fed is likely only to increase as the 2020 elections approach: if President Trump is able to engineer further cuts, and then get the markets soaring with a trade deal and promises of tax cuts just in time for elections, we might begin to agree he is – in his words – “a very stable genius”.

For now the UK seems to have escaped the global disinflation which started in Japan and is now being seen in Europe. That fits the BoE’s line, which is that they plan to hike rates, irrespective of the outcome of Brexit. Mark Carney has even warned investors that they are underestimating how much interest rates could rise. Does the market believe him? It’s certainly not our base case: the strategy of hawkish language to prep the market for rate hikes evidently didn’t work for Jerome Powell. If the UK does leave the European Union on 31st October without a deal, UK growth is likely to suffer – if the BoE’s goal is financial stability, it would be hard to justify a rate hold, let alone hike. So far the BoE’s forecasts are based on the assumption of an orderly Brexit, but they have made no public change to this in light of the ever-growing likelihood of a hard exit.

Some investors argue that a lower sterling (inevitable in the event of a ‘no deal’ Brexit, and also likely if the BoE engages in quantitative easing) would lead to considerable imported inflation due to increased export demand. This would justify a hawkish policy response. Here, however, a direct parallel may be drawn with that which we have witnessed in the US this year. The data in the US (strong wages, low unemployment, a solid consumer) may well justify a continued hiking cycle, but with a nervous market which has been placated by the promise of monetary easing, would a rate hike really help economic stability? The Fed evidently asked themselves this question and didn’t think so. Unlike in the US, rate cuts are not priced in by the UK market so far: currently, the implied probability of no change at the next MPC meeting is close to 100%, while in the US the implied probability of another cut in September’s FOMC meeting is close to 100%. But in the event of a ‘no deal’ Brexit in a month’s time, market expectations going forward may well be very different.

There are other uncertainties which will follow Brexit. Many now expect a general election to take place shortly after 31st October. Would a Corbyn-led government follow a similar nationalization of governmental institutions as of infrastructure? It would certainly increase fiscal spend, leading to considerable debt issuance and downward pressure on gilt prices from increased supply. And given that higher interest rates promote the interests of asset-owners/lenders over borrowers, it is likely that such a government would seek to lower the cost of borrowing in any way possible.

And which rate should be thought of as “neutral” anyway? The 2% CPI target which the BoE follows has been changed in the past. In a post-Brexit world of potentially dampened growth prospects, it may be that this already fairly arbitrary number faces pressure. With low inflation and growth around the world, we would argue that it is fiscal policy which should concern itself with growth, and monetary with inflation.

For now the Bank of England continues to plough its lone furrow of hawkishness. But as the clock ticks down to 31st October and a hard Brexit seems ever more likely, it may be hard for the new BoE governor to avoid joining the loose money bandwagon.

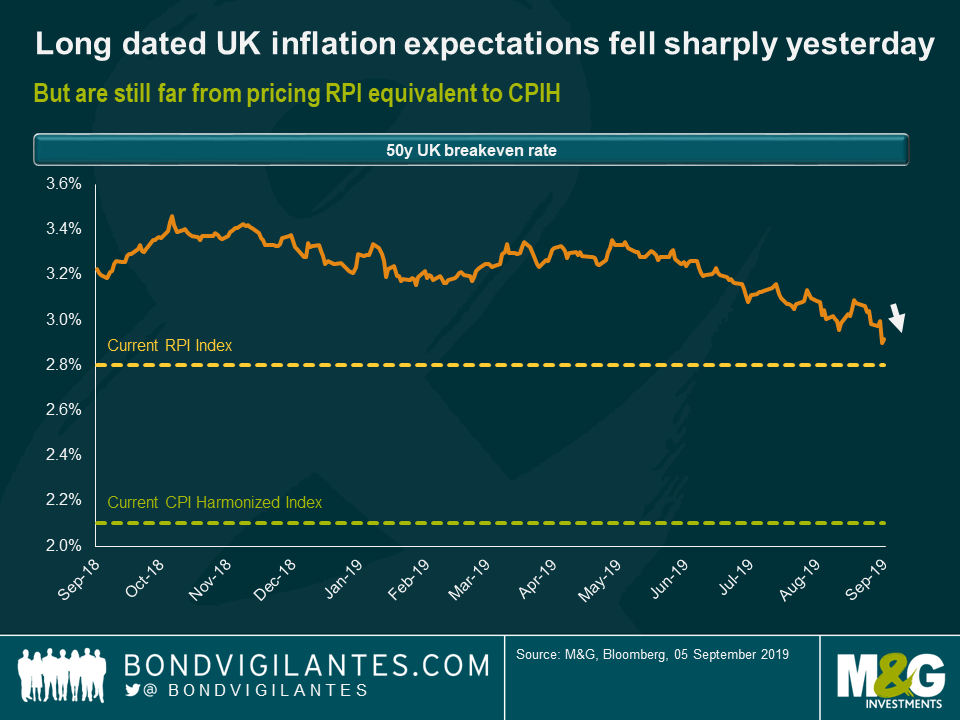

Index-linked markets were sent into a tailspin yesterday as Chancellor Sajid Javid responded to an earlier letter from the UK Statistics Authority (UKSA), which had set out recommendations for the reform of the RPI. The longest-dated linkers (maturing in 2065 and 2068) fell by more than 9% as breakeven rates plummeted.

Javid’s response contained three big shocks for index-linked markets:

- RPI to be aligned with CPIH – while Javid ruled out the possibility of RPI being scrapped, citing the potential disruption for the many users of RPI, he did appear to support the idea of fixing RPI by aligning its methodology with CPIH. Since CPIH is typically around 0.8% lower than RPI, this would of course have a significant impact on the future returns of index-linked gilts.

- Changes could be phased in by 2025 – the letter also revealed that the changes to RPI could be brought forward to as early as 2025, potentially affecting a larger part of the index-linked market and over a longer timeframe than originally envisaged.

- New risks for long-dated linkers – by far the biggest shock was the revelation that once all the old style linkers have matured in 2030, the statisticians are free to make any changes to RPI that they want, and without the prior approval from the Chancellor. While this critical point was stated in the statistician’s letter sent in March, incredibly this was not published. Investors have therefore been buying and continuing to own linkers maturing beyond 2030, completely blind to this fact.

Despite the extent of yesterday’s moves, it’s worth noting that breakeven rates yesterday only fell by between 10-15 bps. The wedge between RPI and CPIH, however, is around 80 bps, which means breakeven rates could potentially fall a lot further if RPI is eventually brought fully in line with CPIH. Following yesterday’s revelations, we now know there is nothing to stop the statistician from doing precisely this from 2030, once the UKTI 4.125% 2030 matures.