Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts has big plans. She dislikes the path the United States is on and wants to make fundamental changes to the economy. These plans include much tougher regulation of banks, a breakup of large ‘monopolies’ — her first sight is on technology companies — and also a healthcare system based on a single payer principle. Just under a year from the US Presidential election, the current Democratic front runner has laid out her plan for “Medicare for All.”

The Warren plan estimates federal spending would need to rise $20.5 trillion over 10 years to fund this. To put this number into context the US government’s entire public debt is currently $22 trillion.

Warren has proposed the following targeted tax increases:

- Wealth tax of 2% on individuals with assets more than $50 million

- Wealth tax of 6% on individuals with assets more than $1 billion

- Tobin tax of 0.1% on all financial transactions

- Top 1% of households to pay capital gains on all assets – including unrealized gains

- Stricter tax compliance on foreign earnings – these would be taxed at 35% (equal to a restored 35% US corporate tax rate from 21%)

- A new employer Medicare contribution to raise $8.8 trillion

Ensuring healthcare coverage for all is not an ignoble cause. However, these tax policies would represent a fundamental change in US domestic policy, going back to fiscal policies last seen in the 1960s and 1970s with President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society plan. The fact that Elizabeth Warren is rising in the polls, while centrists like former Vice President Joe Biden are falling, mean these plans cannot be ignored. Couple this with impeachment hearings that the House of Representatives has just opened on President Trump and we are likely to see a volatile 2020 for US markets.

If Warren gains the nomination (we should know by May 2020, with the first Democratic nominee election at the beginning of February 2020), and if Trump is not polling well into June/July 2020, there is a chance we could start to see investor fright and capital flight from the US.

How likely are these plans to become reality?

The 2020 election will likely keep a Democratic House of Representatives (lower house) and return a Democratic Senate (upper house). This will make it easier for a Democratic President to enact their policies. However, the US Senate is a more conservative chamber (even if Democratically controlled), so these policy ideas would be watered down.

A wealth tax will also likely be challenged as unconstitutional in the US, and likely will make its way to the US Supreme Court which, for the foreseeable future, is likely to keep its conservative tilt.

Healthcare costs in the US remain disproportionately high compared to all other developed nations, so remain cautious on healthcare companies going into an election year. Both parties are likely to try and appease voter concerns.

The road to the White House runs through the Mid-West

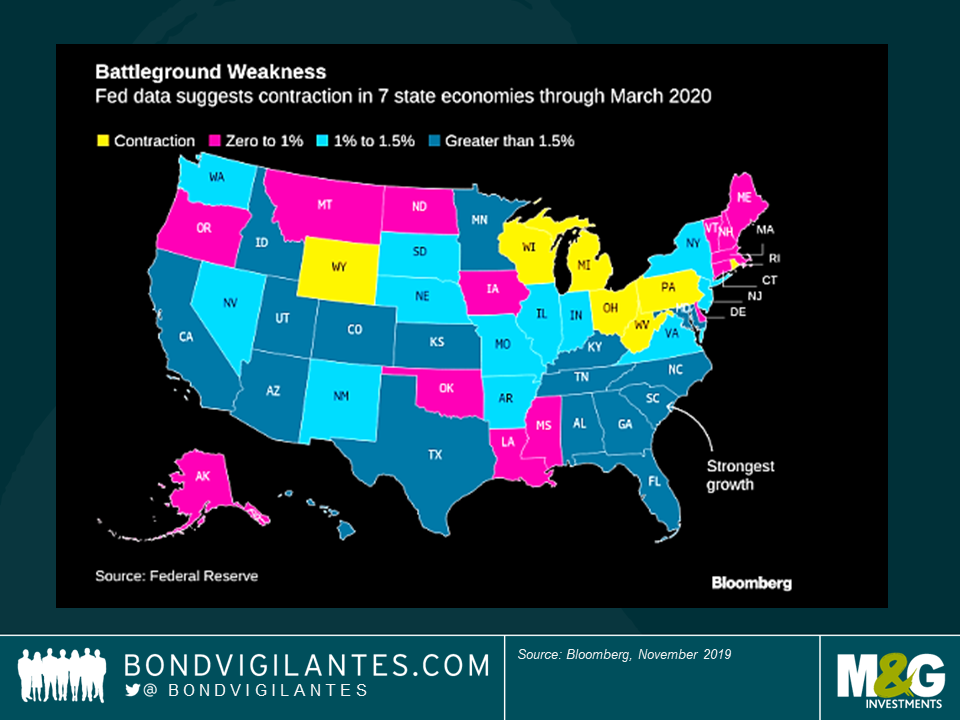

States that swung the election for Donald Trump in 2016 were the rust-belt states of Pennsylvania, Ohio, Wisconsin and Michigan, reliably Democratic states for the past 25 years. In a worrying sign for Donald Trump, these states are among the ones that face economic contraction over the next 6 months according to Federal Reserve data (see chart below), predominantly due to the US-China trade war. Currently, polls show the President has the support of the US electorate in his trade negotiations with China, but should the economic data continue to deteriorate it will be a concern for his re-election chances.

The best predictor in the past of a President’s re-election chances has been US consumer confidence. In the last 40 years, only two Presidents have stumbled at a re-election attempt — Jimmy Carter (1980) and George H.W. Bush (1992) — both of whom faced weakening consumer confidence at home. US consumer confidence has defied the deterioration so far in business investment, but the two do not usually remain in opposite paths for long.

Are the financial markets pricing in a change in policy?

As US equity indices continue to hit all-time highs and US Treasury yields remain near all-time lows, so far the market is not factoring in policy change. Implications for a substantial increase in government spending are not being factored into US government bond yields, and nor is a material increase in the US corporate tax rate into equity markets.

With two new centrist Democrats (Michael Bloomberg and Deval Patrick) looking to enter an already crowded field, the indication is that Democrats are not happy with their current options, while centrists candidates believe they have a chance to clinch the nomination. As we have seen in the UK with the Labour Party, the party membership can differ widely from the views of the mainstream population, so the odds still remain in Elizabeth Warren’s favour to be the Democratic candidate.

The US, which has been a consistent beacon of returns for all investment classes since the financial crisis, is entering a period of increased volatility, where poll ratings will be as important as quarterly GDP figures, Federal Reserve statements and company earnings.

Earlier this month, Germany celebrated the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, a pivotal moment in recent history that left the Soviet-led communist bloc on the brink of collapse. Whether the Hoff was single-handedly responsible or not, the reunification of communist East Germany with capitalist West Germany was a unique economic shock with a number of potential lessons. Changing demographics, the introduction of a unified currency and tight monetary policy are some of the key changes from this period that have shaped what modern day Germany looks like. While there have clearly been huge strides made by the East since reunification, unrest still exists between the East and West – as Germany is currently facing the threat of another recession, we take a look at whether this gap will close any time soon.

The reunification of a divided population led to over 1 million people taking advantage of their newly found freedom by moving West. Citizens were liberated from a humiliating surveillance state and were free to travel, express opinions and choose their leaders. Today, some East German regions have lower unemployment rates than West post-industrial regions like the Saarland or the Ruhr valley. However, it was not all plain sailing for the East Germans. Having been brought up for four decades in an environment of oppression and indoctrination, many could not suddenly adapt to the rigours of capitalism. As average productivity levels in the East were only 30% of those in the West, estimates suggest that up to 80% of these unproductive Eastern workers found themselves out of work at some point during these transition years as they adjusted to a new regime. 8,500 companies in the East were privatised or liquidated by the Treuhand, a newly founded and highly controversial government agency. Most of the liquidated assets fell into Western or foreign hands, hindering the development of an Eastern capitalist class.

Eventually, the convergence between East and West ground to a halt – today, just 7% of Germany’s most valued 500 companies (and none listed in the DAX30) are headquartered in the East – this starves municipalities of tax revenue and contributes to the East-West productivity gap, which stood at around 20% for 20 years. Labour productivity and levels of industrialisation still lag behind the West – median wages are still 20% lower than in Western states for the same work. Many feel the East is still ‘ruled’ by the West, with East Germans holding barely 4% of elite jobs in the East and many renting flats from Westerners, who own most of the housing stock. Changing demographics also pose a risk, as due to the mass movement of youngsters, the East has an older population than the West. Since 1990, the number of over 60s there has increased by 1.3 million despite the overall population falling by 2.2 million. This demographic decline poses a threat to the productivity of the Eastern working-age population as limited new talent is joining the bottom of the East German career ladder. Despite narrowing since reunification, there is also a risk that the gap between West and East living standards will actually widen going forwards, as although overall emigration to the West is slowing, Eastern cities are now sucking up the educated workers from struggling small towns and villages.

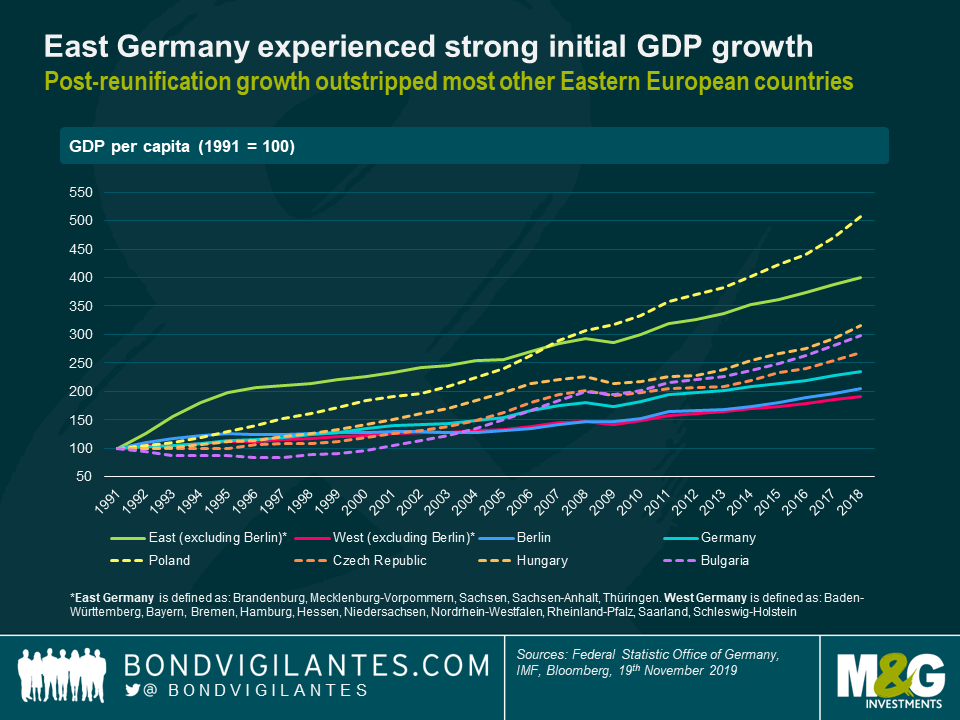

These trends can be observed in terms of economic growth on a national level, where East Germany experienced strong, non-inflationary GDP growth during the early 1990s after reunification initially spurred demand in the region. West Germany however, seems to have experienced very little growth in GDP per capita throughout the early 90s, despite initially coping rather smoothly with the strains that unification put on its resources. Germany as a whole experienced sluggish growth in the 90s, which many attribute to the drastic deterioration in Germany’s public finances post reunification. However, it is unclear whether West Germany’s growth slowed due to an influx of unproductive workers from East Germany (where the Eastern economy was only 10% the size of Western GDP), or by poorly timed tight fiscal and monetary policies causing a protracted deflationary economic environment. Nonetheless, despite regional differences and poor overall growth, East Germany still fared better than most other Eastern European countries that shook off communism over the 90s. A glance around the rest of the former Eastern Bloc, where unemployment and poverty tend to be higher, suggests that East Germany was lucky to have had a strong Western state to support its transition to a market economy. The application of Western laws and practices arguably saw off the threat of oligarchic corruption that has plagued many of Germany’s Eastern neighbours, where Poland seems to be the key exception.

Today, these regional inequalities persist and with Germany facing the threat of another recession, it does not seem likely that the gap between East & West will close any time soon – as it stands, the constitutional pledge of “equivalent living conditions” across Germany is looking increasingly unattainable.

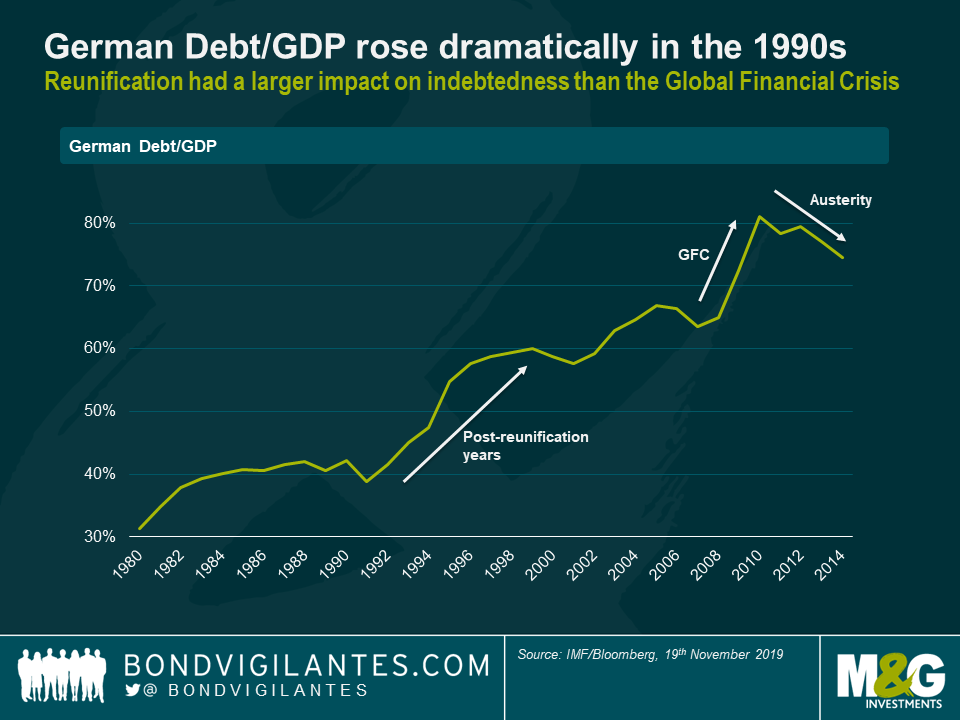

What happened to bond yields post reunification? The Bundesbank attributed almost all of the rise in public debt/GDP since 1989 to the costs of unification.

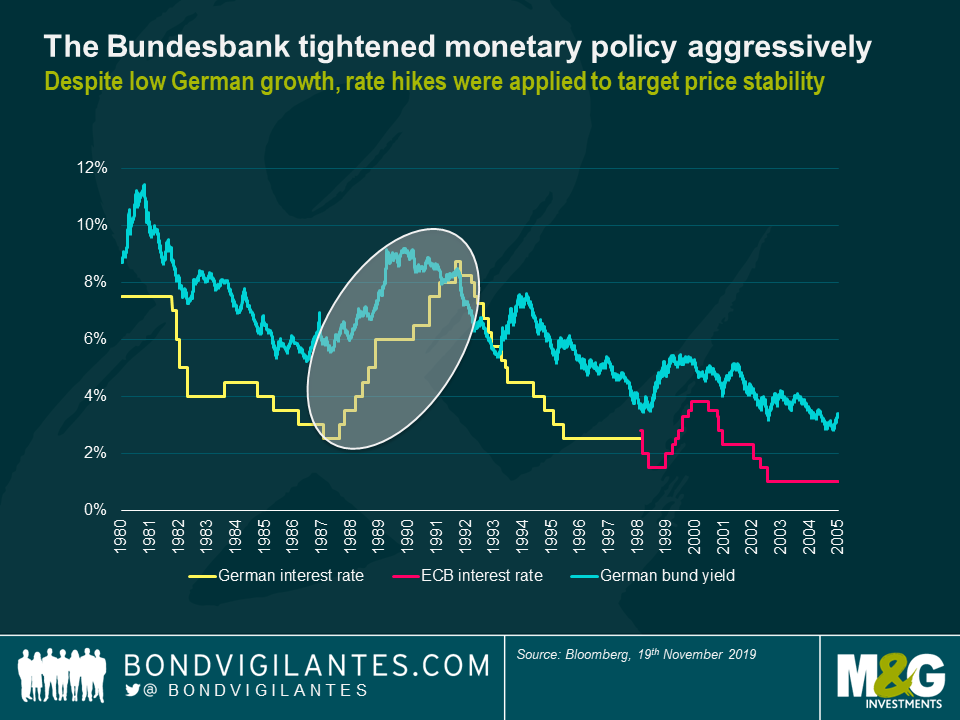

The German central bank thought a key risk for German fixed income markets was that the high speed of reunification could lead to a public sector deficit and thus destabilise inflation and undermine faith in the Deutschmark, the anchor of the European Monetary System. The Bundesbank thus tightened monetary policy aggressively, pushing up German rates by about 3% over 1991 and 1992. As significant increases in taxes and administered prices pushed up inflation, the Bundesbank further hiked rates. Unfortunately, the central bank’s aggressive pursuit of price stability meant German society paid a steep price in terms of high unemployment and continual low economic growth. This stance saw the last real jump in Bund yields that markets have seen since 1989 as the interest burden soared, despite the impact on government bond yields one would normally associate with lower growth rates. The high German rates made it difficult for other European economies to pursue corrective monetary policy actions. The outcome would be the crisis of the ERM in 1992 and 1993. Since then, continual monetary loosening and a ‘flight to safety’ mentality from debt-ridden peripheral European economies have led to investors piling in to Bunds and driving yields into current negative territory.

As part of reunification, there were huge transfer payments (nearly €2 trillion) from West to East. The West German chancellor (Helmut Kohl) converted savings into hard currency at the generous exchange rate of one Deutschmark to one Ostmark. Thus, unlike any other country ever freed from oppression, the entire population of East Germany was given citizenship of a big, rich democracy. The Deutschmark saw increased demand, especially from abroad, as it quickly became a substitute for the Dollar. Despite weak economic growth in the 90s, the Bundesbank’s strict monetary discipline applied to the Deutschmark meant it retained much of its strength as a safe haven currency (before Germany adopted the physical Euro in 2001). However, Germans now seem to be rethinking the concept of sudden internal transfers – perhaps the unified country should have developed a new constitution rather than extend the hand one-way, or perhaps a special economic zone in the East should have been formed, allowing for gradual convergence rather than sudden reunification. Many Westerners feel that investment in the East was made at the expense of investment in other struggling regions, especially as aid measures were initially meant to be temporary. Increasingly, there’s a call for a rethink of fiscal equalization in place of the almost $70 billion a year that has flowed into the former East Germany since 1990.

Subsequently, what are the key lessons that we can draw from these years? Germany’s recent history teaches us that even in a near perfect model, currency integration is difficult. Implementing a unified currency means that struggling economies can no longer use a lower exchange rate to boost exports and thus they remain uncompetitive. The currency union in Germany meant that East German firms suddenly had to compete with Western firms at a similar level of prices, wages and costs, despite a much lower level of productivity. Industrial output dropped by 35% in the first month and fell by another 15% in the next month. This basic flaw of a single currency can be seen through the struggles of member economies in the Eurozone, particularly peripherals, where once economies begin to diverge from one another, a common currency and monetary policy can cause the divergence to increase. In terms of lessons for bond markets, Bunds are a reasonably unique case as typically government bond yields follow weak nominal GDP growth. However, during reunification yields jumped around 150 basis points despite weak German growth. Since then, Bund yields have fallen due to a combination of weak growth and investors in peripheral economies piling into Bunds during times of uncertainty.

To conclude, Germany is a reminder of the importance of history and path dependency. Going forward, the differences in East Germany’s cultural and institutional background compared to the West are still evident in the lives of German citizens today. Discontent is still prevalent on both sides of the now-crumbled wall, and 30 years on, East Germany is still waiting for the economic upswing that the currency union was designed to trigger.

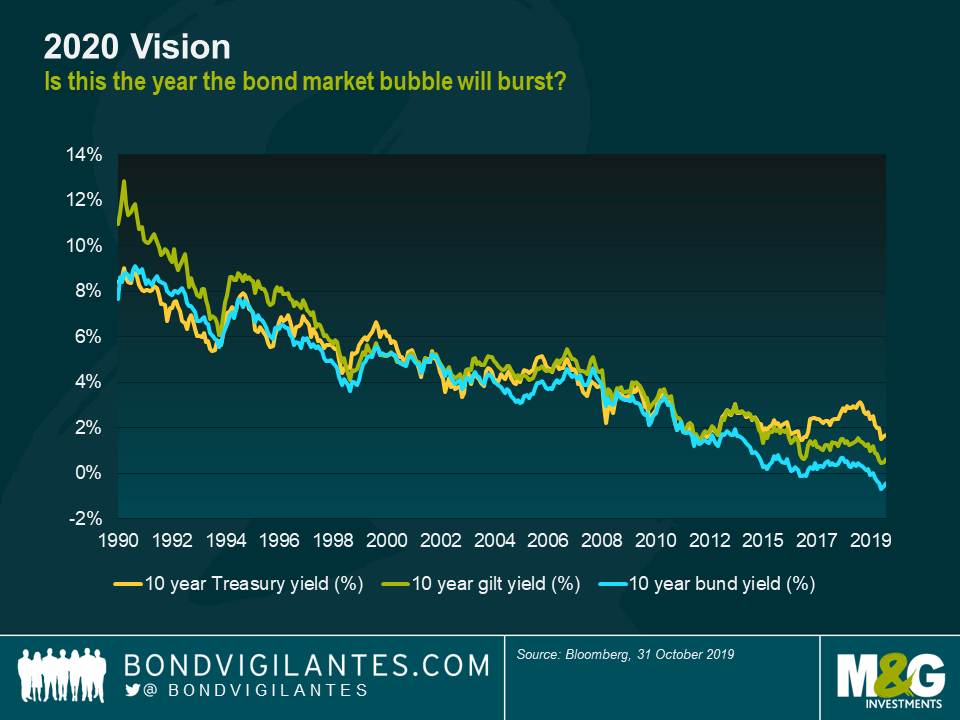

Let me start with two predictions. Firstly that the title “2020 Vision” will be irresistible to all year-ahead outlooks, no matter what publication or industry you work in. This is why I trademarked the idea many months ago, and now expect to retire on the proceeds of all the copyright breaches. My second prediction is that in my industry, bond fortune telling, virtually all of those 2020 outlook pieces will declare that it will be the year that the “bond bubble” bursts. Maybe they’ll be right this year, after a 30-year streak of “sell bonds” predictions. But their track record doesn’t suggest they have an edge in the bubble popping business.

If you do believe that 2020 is the year for bond bears finally to triumph, I think you have to believe that a lot of very long term, established trends are about to come to an end simultaneously. These trends are the Secular Seven. If you think that their powers are at an end, or significantly diminished, then you should join the January anti-bond mob with their pitchforks and flaming torches. Otherwise you’ll probably want to wait to see a conclusive break in the 30-year downtrend in bond yields and inflation before saying goodbye to fixed income.

The Secular Seven

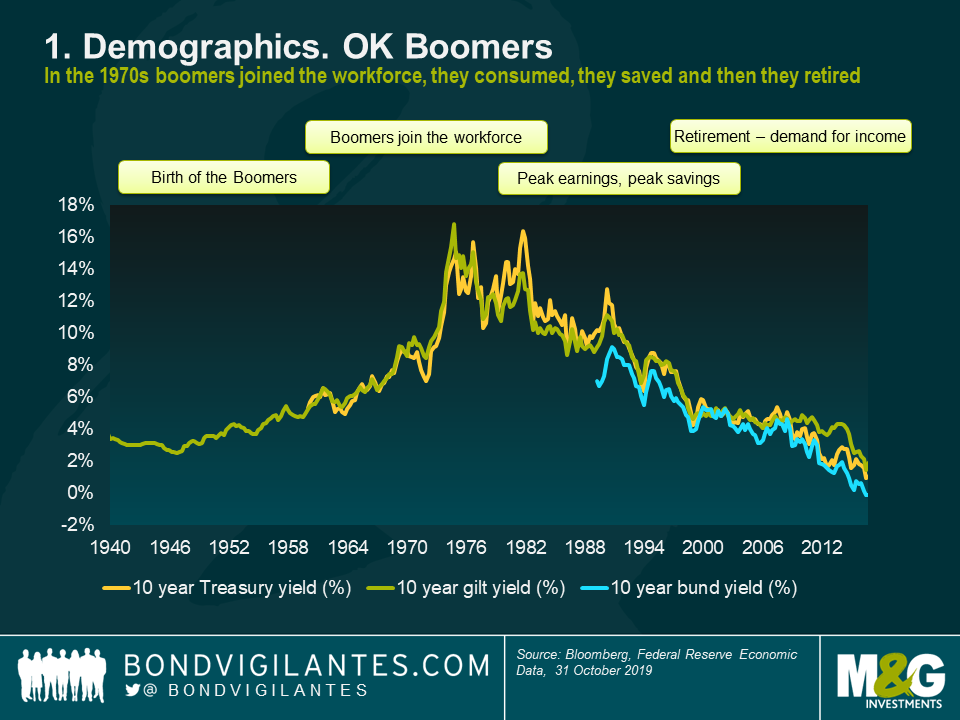

1 – Demographics. OK Boomers. The post-World War 2 baby boom impact on the economics of the developed economies can’t be overstated. In the 1970s and onwards as the Boomers left education and came to dominate the workforce, the labour scarcity that had been a feature of the western economies for a couple of decades started to come to an end. Trade Unions lost their membership and their power, and wage inflation dropped. Economies became more productive, and wealthier. With largely young and healthy populations, pressures on the welfare state (for example pension burdens, and care and healthcare costs for the elderly) were relatively subdued. As the demographic basketball (the Boomers) passed through the snake and reached peak earnings, their desire to save and invest those savings also hit new highs. Demand for income and safe assets grew dramatically – driving bond yields down.

2 – Technology’s impact on inflation. Why can’t we generate consumer or producer price inflation in developed economies despite zero or negative interest rates, “money printing” and periods of growth and low unemployment in the past decade which historically might have generated CPI of at least twice the current common inflation targets of 2%? The dramatic deflation in consumer goods is one answer, and a good part of that has been driven by the collapse in the price of technology. The 1996 Motorola StarTAC mobile phone cost $1000 then; a similar level phone today is about $200. 1996 was probably also the year I stopped hiring a TV (paying monthly) from Radio Rentals and bought one, as they’d become affordable. And it’s not just the cost of the hardware: I used to spend at least £50 a month on music on compact discs (and cassettes before that, which I note are now fashionable with youngsters). Now I pay £12.99 a month for all the music in the world on Spotify. Think also of all the free stuff that the internet provides, from maps to encyclopaedias and news, and perhaps the impact of low inflation is actually understated. The transparency of the internet also allows me to find the cheapest thing in the world whenever I buy something. Awful news for high street retailers, but the deliverer of a huge consumer surplus and disinflation. Finally, we haven’t even discussed the Rise of the Robots yet: what if AI and robotics are finally deployed in the workforce on a massive scale? What does that do to wages? To employment and disposable income? It certainly sounds like a further technological leg down in price inflation is possible.

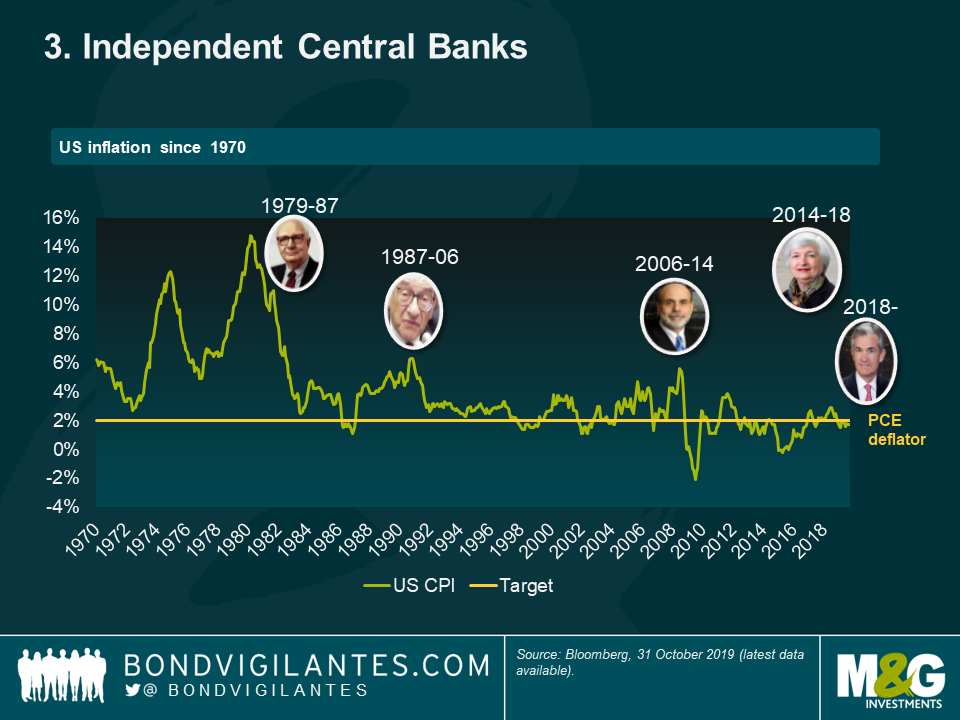

3 – Independent Central Banks. When Paul Volker was appointed Chair of the US Federal Reserve Bank in 1979, inflation in the States was 11.3%, peaking in March 1980 at 14.3%. US Treasury Bonds were thought to be almost uninvestable as yields were eroded by the rise in the cost of living. Volker set the Fed Funds rate above the rate of inflation – at the time a radical idea. Inflation fell steadily through his tenure, and an “inflation fighting central bank” culture was established. This led to explicit inflation targeting around the world, from New Zealand through to Gordon Brown making the Bank of England independent, and on to an ECB which was so wedded to this inflation-fighting mandate that its President, Trichet, hiked rates twice in the midst of the Global Financial Crisis on the grounds that oil prices had risen year on year and had taken eurozone CPI above 2%. Central bankers have certainly taken a lot of the credit for the bond friendly environment we’ve been in for the past couple of decades, but it’s clear that this separation of their powers from elected politicians coincided with some arguably more powerful trends.

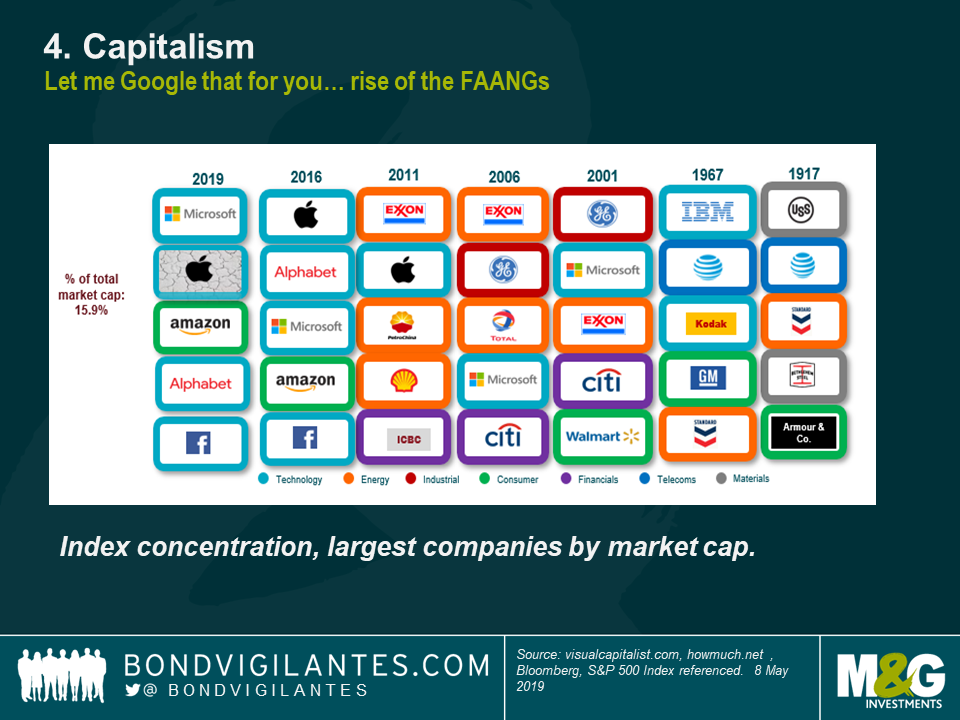

4 – Capitalism. As labour has become less powerful since the entry of the Boomers into the economy, capital gained the upper hand and has taken the bigger share of profits and growth in developed economies for years now. Governments have deregulated financial markets and labour markets (with some notable exceptions like the introduction of the Minimum Wage in the UK), and the emergence of the new tech giants (the FAANGs) has led to both increased competition in some areas (Amazon has delivered massive consumer surplus in its race to acquire market dominance) and monopoly creation in others (Google is a verb as well as an online advertising giant). Capitalism has thus kept wage growth low, and encouraged the growth of a tenuous gig economy landscape. Whilst there are examples of monopolies developing, as the land-grab continues, prices have stayed low. Take a look at some of the bloggers in the US who write about existing on free trial subscriptions (everything from mattresses to groceries) and half price food delivery offers as companies try to buy some market share. I’ve got a 50% off Uber Eats trial in my inbox right now. Burger or pizza?

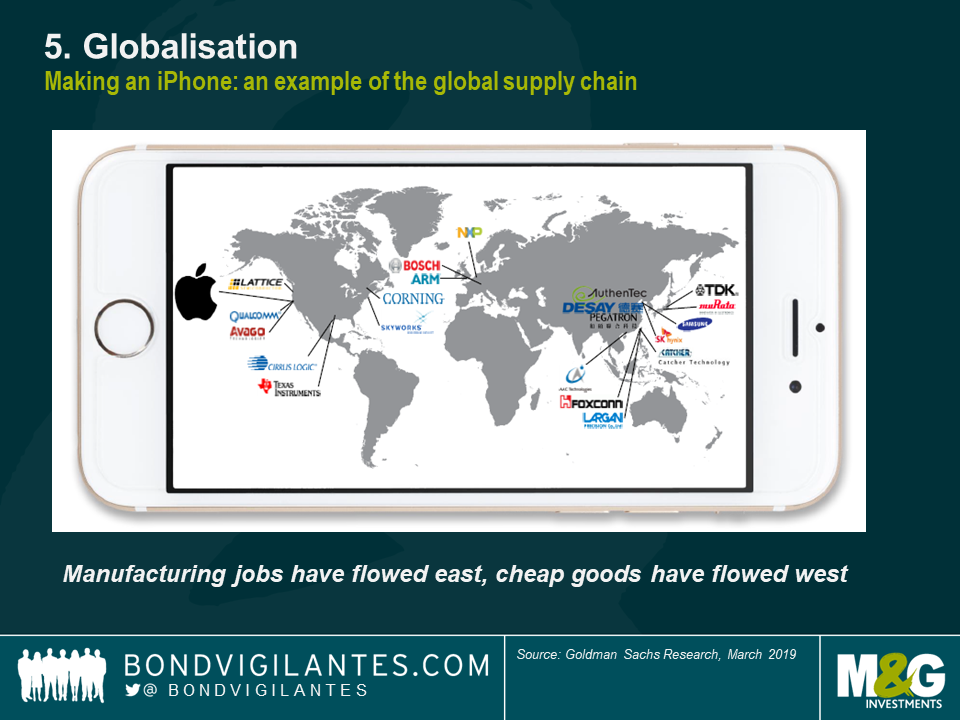

5 – Globalisation. China joining the World Trade Organisation in 2001 didn’t start the process of globalisation, but it did signal that everything had changed, especially for manufacturing companies. The supply chain became a global one, and goods prices collapsed as we all imported cheap stuff made by people earning fractions of western wages. The liberalisation of trade barriers and tariffs, together with advances in the logistics and cost of containerisation and shipping, meant that manufacturing jobs went east and cheap goods flowed west.

6 – The Austerity Meme. I’ve been fascinated by the Reinhart & Rogoff “This Time is Different” book ever since it came out. Flawed in some of its initial calculations, its narrative of higher government borrowing leading to economic disaster nevertheless set the scene for a decade of austerity in many of the economies hit hardest by the Global Financial Crisis. Now the relationship between government borrowing, bond issuance and bond yields is surprisingly weak: you’d think that as governments issued more bonds, prices would fall. This turns out not be true historically, as times when governments borrow more have usually been those times when growth and inflation are weak. Nevertheless, the UK for example has seen relatively low bond issuance since the GFC as the result of the longest period of austerity recorded. Germany is running a budget surplus, despite stagnant eurozone growth. It’s therefore possible that this period of relatively low bond issuance at a time of weak growth has delivered lower bond yields than we’d have normally had.

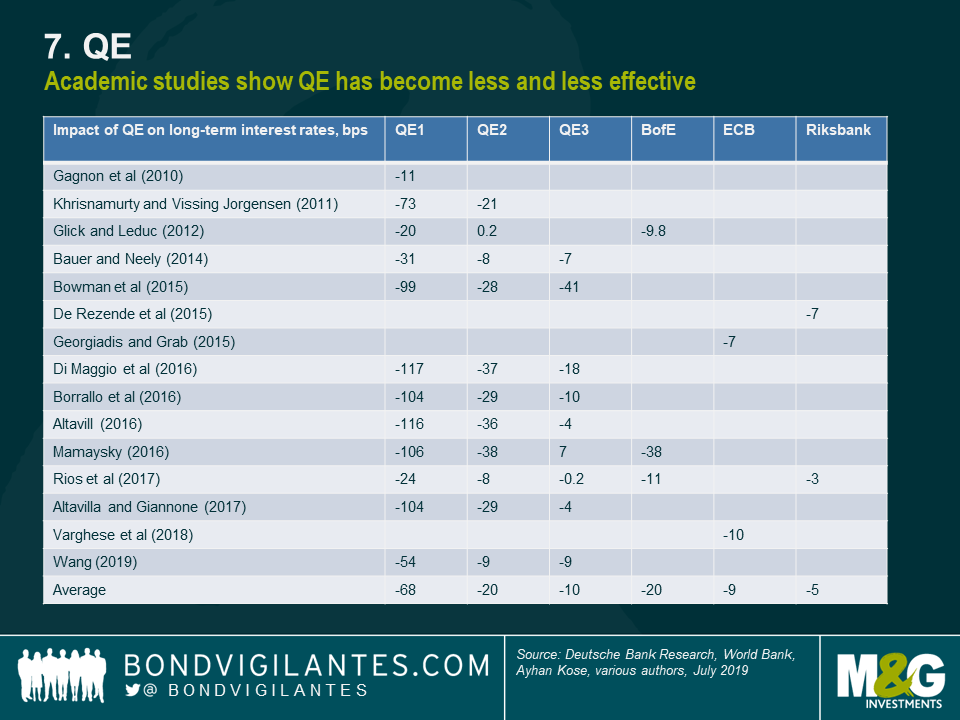

7 – QE. We’ve had 3 rounds of Quantitative Easing from the Fed since the GFC. The Bank of England has also bought both gilts and corporate bonds. The Bank of Japan and the ECB have also massively expanded their balance sheets in bond purchase programmes. And the ECB has just announced endless QE in Mario Draghi’s parting policy announcement. Does QE reduce bond yields? Yes. A study of all the academic papers on the impact of QE around the world showed that on average the three rounds of US QE reduced US Treasury Bond yields by about 70 bps, 20 bps, and 10 bps respectively. Whilst inflation remains below target in most of the developed economies, it’s unlikely that we see any unwinding of the bonds held on central banks balance sheets – in fact some of us think that these bonds will never be set back into the wild, and will mature in the dark of those central bank vaults.

So are any of the Secular Seven under threat?

Yes. Many of them look to be less powerful than they were at their peak, although it’s possible that we’ve only so far seen the first stages of technology’s impact on wages and inflation: companies are sitting on cash piles that will be invested in productive technology at the first sign that their flesh and blood robots are achieving higher wages. An example of this in action was the introduction of self-service ordering systems in fast food restaurants after minimum wage increases for workers in those US businesses.

Demographic trends remain in place, although the never ending increases in life expectancy that we’d come to expect have stalled in some demographics, thanks to obesity related illnesses and opioid addiction. There are also some stark differences across the developed world, with birth rates in the US much higher than in parts of Europe, implying higher potential growth rates in America in the future. Japan shows us that even when labour force growth peaks and declines (Japan is a decade ahead of the west demographically), this isn’t enough on its own to combat entrenched deflationary forces.

Have we had enough of independent central banks? Donald Trump certainly has if you read his tweets over the past year. Fed Chair Jay Powell has come under immense pressure to cut rates towards zero again, and if Trump is re-elected in 2020 you have to imagine that Powell is replaced by someone more willing to turbo charge the US economy. In the UK, Mark Carney remains as the Bank of England Governor for the time being, but you could imagine some post-election outcomes that deliver some partisan choices as his replacement. Incidentally, the Bank of England just announced it is changing the title of its Inflation Report. It will now be the Monetary Policy Report which, if Sod’s Law has its way, will mark the return of rampant price rises. Central banks took the credit for the collapse in inflation over the past thirty years – and as I’ve discussed they were just one smallish part of that story – so they shouldn’t be surprised to take the blame now that inflation is too low for comfort, and this will undoubtedly threaten their mandates.

Whether capitalism’s dominance of the economic system continues to the same extent rather depends on a couple of rather important election results. On the electoral front, whilst neither candidate is a bookmaker’s favourite to take office, both Jeremy Corbyn in the UK and Elizabeth Warren in the US have a chance of power, and both have radical agendas which would likely involve higher rates of corporation tax, wealth taxes, financial transaction taxes and higher government spending. Monopolies in the tech space could be broken up, and financial regulation could tighten once more. Nationalisation of some industries couldn’t be ruled out. After a period of right wing populism in the UK (Brexit) and US (MAGA), the pendulum might swing the other way, and the left could take its revenge. Coupled with existing protectionism movements in the US (the trade war with China could be cooling, but has already damaged the global economy) and new European trade barriers post-Brexit, the left’s anti-globalisation philosophy (on the grounds that it produces a race to the bottom in workers’ rights) could exacerbate the stalling on global trade flows.

We go into 2020 then with some of the tailwinds for falling bond yields having been diminished, and one in particular – that of the austerity meme – likely to have turned into a headwind, with some potentially large increases in government borrowing in prospect. Also importantly, our starting valuations for “risk free” assets are unattractive, with most developed market government bonds having negative real yields. I don’t believe that a negative real yield is in itself an aberration, and we should come to regard the elevated real yields of the 1980s as the exception rather than the rule (you could get RPI plus 4% when you invested in index-linked gilts for a time), but clearly government bonds are expensive historically.

All of this means that I too will end 2019 with an underweight view on government bonds, expecting yields to move higher next year. But on any significant move up in bond yields, I’d want to buy back my gilts, bunds, Treasuries and JGBs, as many of the Secular Seven trends remain powerful, and there are clearly significant economic and social fragilities in the global system that could trigger further central bank policy moves – both traditional (rate cuts) and extraordinary (rate cuts below zero, more QE) – and a new flight to quality. We ain’t out of the shadow of the GFC just yet, and with more debt in the global system than there was in 2007, rising bond yields themselves could trigger the next big downturn.

Finally, remember that the global government bond market sets the “risk free” rate which is the major input in the valuation of all asset prices – from corporate bonds, to equity, to property. So if you are expecting a bond blood bath, the impact on other asset classes could be even more severe…

Christmas has come early for Europe, with Mario Draghi’s goodbye present to the market of further quantitative easing (“QE”). The ECB has kicked off its latest round of asset purchases. While this will undoubtedly be supportive for European credit, I feel much of the impact is already priced in to the secondary market. With a large book to fill, a significant part of the ECB’s ammunition is likely to be deployed in the primary market.

The ECB buying will clearly be supportive for corporate bonds, but just how material is the buying going to be? Wolfgang Bauer recently wrote a blog (here) looking at the impact of this latest round of QE. This time, the ECB is buying from a much lower base.

To assess what impact they might have, I think it’s useful to look at the volume of supply we’ve had, and probable ECB participation going forward. Looking at the breakdown by investor type for the recent Daimler new issue (A-rated by Fitch) from 30th Nov as an example, I estimate that around €535m of the €4bn deal was bought by the ECB – a rough exercise admittedly. This is a significant amount of the expected purchases per month (around 10% if we assume higher end of €5bn of purchases per month). And this is 13% of the €4bn deal too.

Shell also issued €3bn on 4th November which priced in line with the existing secondary curve. I estimate ECB participation was around 25% of this deal – a further €750m. If the ECB continues to buy such a significant proportion of issuance, we will likely see investors priced out of new issuance as deals come with zero new issuance premium. This primary participation will be very important dynamic to monitor, and one which investors will be watching for a number of prolific issuers – with VW another likely contender.

We have had a bumper year of corporate supply, largely due to low financing costs in Europe. A large proportion of this has been ‘reverse yankees’ – US issuers taking advantage of low Euro financing costs. I have excluded these from the analysis as the ECB can only purchase European issues. Still, YTD 2019 issuance has been €476bn (up 27% from last year). The chart below shows the total senior corporate supply, ex reverse yankees, for last three months across all credit ratings.

The practice and velocity of ECB buying will be a supportive factor for spreads in November but, in my opinion, this will be reasonably small in absolute terms. The ECB and its buying boots have undoubtedly boosted market sentiment but, after the initial Dealer inventories of high quality eligible paper have been hoovered up by the central bank, the greater extent of the move will be in its effect on wider BBB eligible names and non-eligible paper – so-called beta compression.

I expect the ECB will come out the traps at a good pace. Expectations for supply in November remain healthy, albeit reducing, so the run-rate is likely to be ahead of the long-term rate in the early phase of the programme. Today will be an interesting date as we will have a summary of ECB purchases from last week – so we can see for ourselves how busy the central banks have been!

ECB purchases are expected to increase in 2020 as redemptions from QE round one roll off. This technical tailwind will therefore increase in strength and undoubtedly continue to be supportive for spreads. However the effect of CSPP crowding out investors, particularly in the primary market, seems far more diminished in the face of declining European growth. Investors are cautious on moving down the capital structure with valuations looking ever more stretched versus fundamentals. As a result, I suspect the most significant effect of the ECB restarting purchases will be to preserve investors’ seemingly already healthy cash balances.