Financial markets are generally considered to be efficient, particularly in the long run. However, in the short term inefficiencies might emerge, especially in times of severe market stress conditions such as the one we are currently experiencing. This can give active investors an opportunity to take advantage of these dislocations until the market corrects itself.

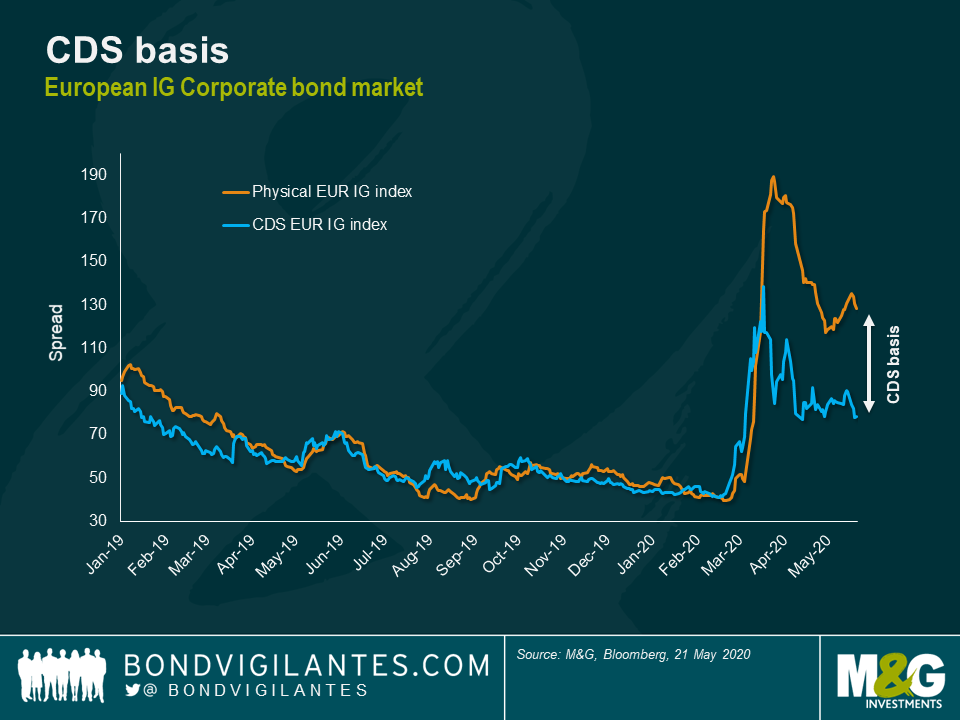

Today amongst various dislocations observable in financial markets, one which is worth highlighting is the so called “CDS basis”. The CDS basis is simply the difference between the spread an investor receives when owning a physical corporate bond, and the Credit Default Swap (CDS) of the same bond. In relatively stable market conditions, the CDS instrument and the spread received by investors should be very similar as they both reflect market perception of the credit risk. However sometimes they can differ and this generates the CDS basis. The basis is defined as negative when the CDS trades tighter than the physical bond spread for the same maturity. When the basis is negative investors could earn near riskless return by buying a physical bond and writing protection on that same bond using a CDS with equal maturity.

Many factors can contribute to drive these differences, but the most important ones are liquidity and demand/supply dynamics. Especially at time of market stress, these two factors can have an higher impact on leading the CDS basis to extreme territories. This is exactly what is happening today: due to the coronavirus crisis, liquidity in the market has deteriorated and this is reflected mainly in physical bonds as opposed to CDS indices which are usually far more liquid. In addition, the exceptionally large primary market activity (see latest blog written by Wolfgang) has further penalised physical markets which had to absorb this exceptionally large supply.

The result is that the CDS basis today is extremely negative: as you can see from the chart below, the spread you can earn from owning a physical bond has increased significantly more than the credit risk priced in the CDS market. With primary market activity now slowing down and liquidity gradually coming back towards more normal levels, this dislocation should continue to close down. Furthermore central banks’ Quantitative Easing programmes should contribute reducing the gap even more as they are buying physical bonds and not CDS instruments.

Investors could take advantage of this dislocation by buying physical corporate bonds and writing protection on CDS indices with similar maturity. Also, for investors which already own physical corporate bonds but want to reduce their credit risk in light of the recent rally in spreads, it could be more efficient to do so using CDS indices as opposed to sell physical corporate bonds.

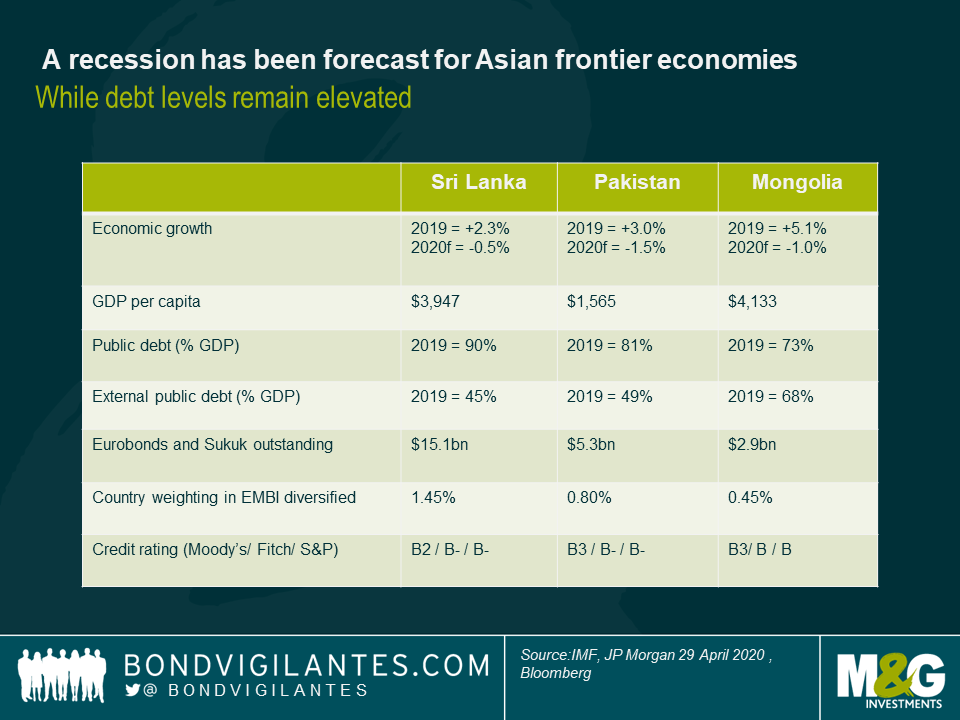

Sri Lanka, Pakistan and Mongolia have each been severely impacted by COVID-19, albeit in different ways. These frontier economies each straddle two worlds. They’re emerging markets in the sense they’ve had access to global debt markets, with their eurobonds included in JP Morgan’s emerging market bond index. But their credit ratings are far below those of investment grade sovereigns, such as Indonesia, who have already been able to issue eurobonds during the crisis. They also still attract significant official sector support as they still have sizeable development challenges. As recent recipients of concessional support from the multilaterals, they were deemed eligible among 70 other countries for the G20’s debt suspension initiative.

A time-bound debt suspension initiative

On 15 April, the G20 launched “a time-bound suspension of debt service payments for the poorest countries that request forbearance”. Questions about this initiative have included: Which countries will be involved? Which creditors will be involved? Will it be considered a default? And how will it all be implemented in practice?

On the creditor mix the G20 stressed that: “all bilateral official creditors will participate in this initiative, consistent with their national laws and internal procedures”. This implied that China – a G20 member – was onboard. The Paris Club has for several decades been the medium for bilateral debt relief but, because China is not in that club, G20 leadership was crucial. The language for multilateral participation was weaker: “We ask multilateral development banks to further explore the options for the suspension of debt service payments”. And regarding commercial debt the G20 said they “call on private creditors, working through the Institute of International Finance, to participate in the initiative on comparable terms”.

Since then, the onus has been on eligible countries to choose whether or not to participate, and to what extent. Most eligible countries have not made public statements about the scheme, but some have confirmed their intention to participate. The Prime Minister of Pakistan and President of Sri Lanka have both publicly pledged their support for the debt moratorium.

Pakistan

The government has been working to bring the pandemic under control. As is the case globally, the radical uncertainty makes GDP predications unusually uncertain, but the IMF has forecast a -1.5% decline in growth in 2020. This would be the country’s first contraction since the 1950s, even though fiscal stimulus has been provided and monetary policy eased in response to the crisis.

The country’s resilience has been supported by pre-crisis reform efforts, made under an IMF programme. This made it easy for the official sector to scale-up their support quickly, including $1.39 billion of emergency financing from the IMF. As an oil-importer, lower global prices for oil have helped cushion the trade balance. But the global crisis is still putting pressure on the balance of payments in 2020, with the biggest hits from reduced remittances and portfolio outflows.

Half of Pakistan’s public external debt service requirements over the next year are to non-Paris club bilateral creditors, with China, Saudi Arabia and UAE by far the largest creditors. A further 20% is owed to the multilaterals, and 25% to commercial creditors. Regarding a debt service suspension, Pakistan recently clarified that it is talking only to bilateral creditors, where its immediate debt pressures are. Despite the clarification that private creditors would not be approached, Moody’s put their B3 rating on a negative watch, in case private creditors are forced to participate on comparable terms.

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka is also facing a recession in 2020, following its necessary response to the virus, reduced tourism, remittances and trade. For example, apparel and textile exports fell by 41% in March and tea exports halved.

The pandemic is aggravating economic vulnerabilities that pre-date COVID-19. The economy suffered from a number of recent shocks and political volatility delayed much needed reforms. Having put off a shift to fiscal prudence, Sri Lanka’s public debt climbed to 90% of GDP in 2019.

While Pakistan got rapid emergency financing from the IMF, Sri Lanka’s request could not be met as quickly. The current IMF programme, scheduled to end in June 2020, required the Sri Lankan government to increase revenue to place public debt on a downward path. But pre-crisis, in anticipation of the election scheduled for early 2020, there were tax cuts. The IMF programme had previously made waivers for missed fiscal targets and would need assurances about the future fiscal path. So a discussion is needed on future IMF support, which is crucial for investor sentiment, but this is tricky conversation to have prior to the election.

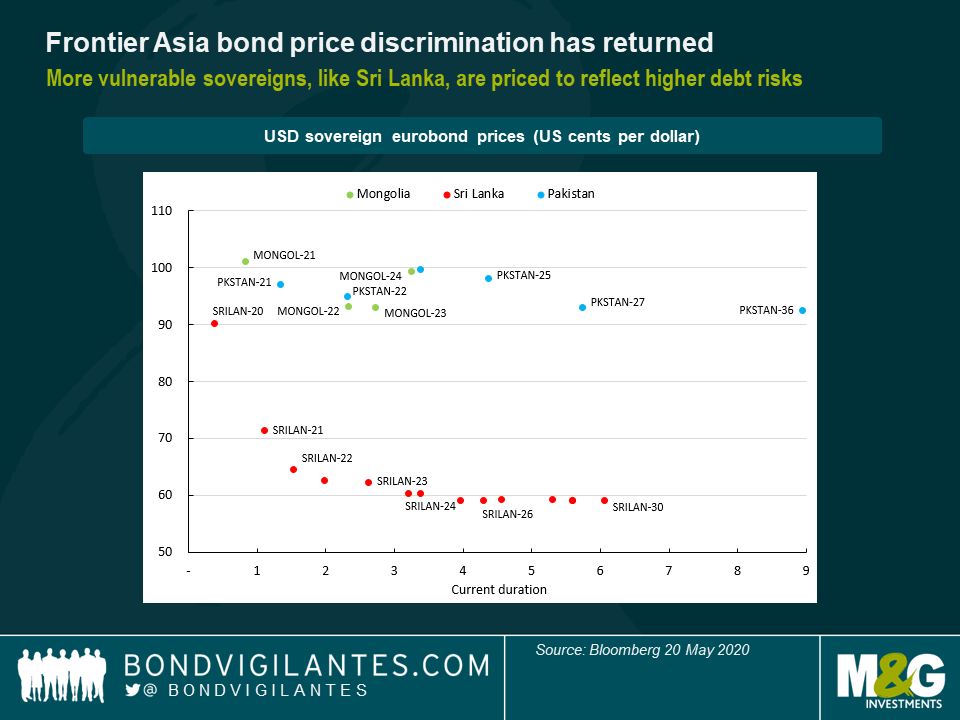

Sri Lanka was going to issue eurobonds in 2020, but since the start of the crisis its spreads have soared into distressed territory. The markets are currently pricing a good probability that the $1 billion eurobond, due in October 2020, is paid. But there is clear doubt to whether Sri Lanka will be able to turn things around over the next few years and remain current on its debt.

In response to such concerns, on 19 May 2020, Sri Lanka’s central banks made a statement “that Sri Lanka will duly honour all its debt service obligations in the period ahead”. Priced out of the eurobond markets the government said it was “exploring bilateral and multilateral sources, plus SWAP facilities with regional central banks” that include India, plus the possibility of syndicated financing to bridge the gap until market sentiment improves. Little mention has been made of debt suspension since the President had encouraged it in April. The next day S&P downgraded Sri Lanka to B-, but did not make any mention of debt suspension in their press release.

Mongolia

As of 20 May 2020, Mongolia had recorded 140 cases of COVID-19 with no related deaths. Despite the reported success in containing the virus’ spread from China, the economy has still been hurt, mostly because it is heavily dependent on export revenue from copper, gold and coal.

Like Sri Lanka, securing emergency financing has been harder than for other countries. Mongolia’s IMF programme lapsed in 2019 and discussions on a new set of medium-term reforms, needed to stabilise debt risks, had been put off until after the Mongolian elections scheduled for mid-2020. Nonetheless, the IMF has signalled that emergency financing will eventually be made available, even if discussions on future engagement take longer.

Mongolia has managed to reduce public debt to 73% GDP in 2019, from 88% GDP in 2016, but the crisis has halted this trend towards improved debt sustainability. Like in Pakistan’s case, its bonds are currently trading at levels that suggest market access is not an immediate option but, if market sentiment continues to improve for frontier markets, it might soon return as an option.

Does a debt suspension make sense?

The COVID-19 crisis has clearly worsened the debt metrics of Mongolia, Sri Lanka and Pakistan. But not ruinously so to date. This suggests that approaching private creditors at this point for a debt suspension would be a mistake. It risks further credit rating downgrades, and years of hard won market access might be eroded. Access to capital will be needed between 2021 and 2024 to finance development and for refinancing, so that the countries can stay current on their debts. If a suspension could be limited to some reprofiling of bilateral debt then the burden might be eased in 2020 without damaging credibility. Moody’s reaction to Pakistan’s bilateral debt suspension request suggests caution is still needed here however, as there remains uncertainty about whether comparable treatment will be demanded from other creditors. Eurobond pricing for Mongolia and Pakistan looks to reflect a market view that they will not default. However, eurobond pricing for Sri Lanka sits in a wait-and-see area, as investors make their minds up about whether or not they think further trouble is ahead.

For the poorest countries without market access, it makes good sense to push for as much debt relief as possible. There is no market access to lose. But for countries who have established themselves in the markets, a hard decision is needed, which must be based on the country context. A blanket approach to debt suspension is therefore best avoided: in some circumstances, it will make the crisis worse, by adding a debt or financial crisis to the already severe health and economic impacts of COVID-19.

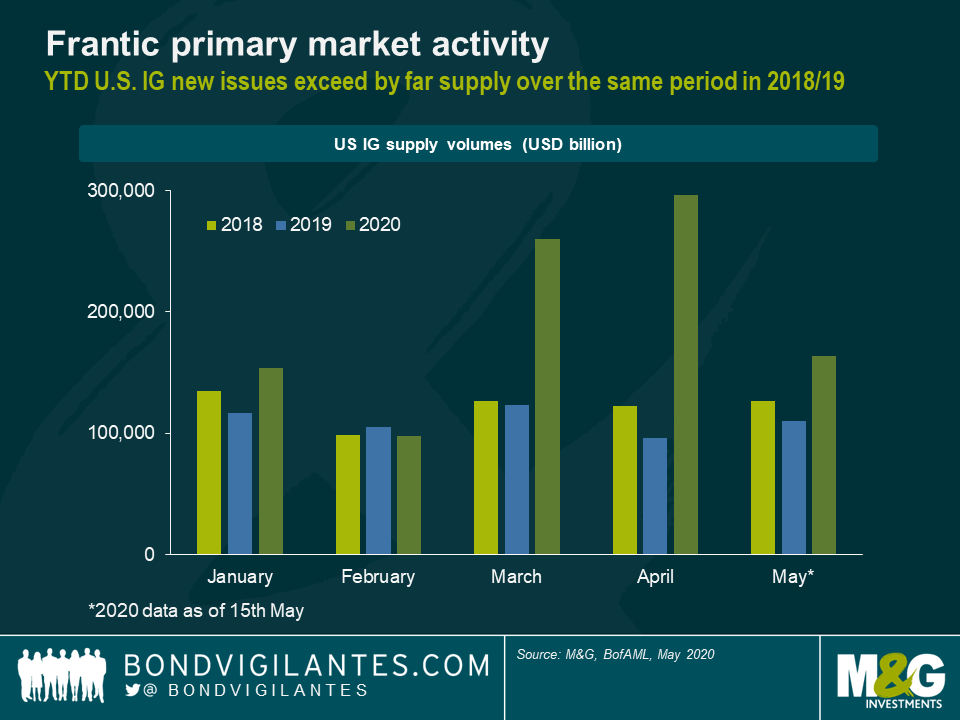

One of the main topics in the investment grade (IG) corporate bond space over the past weeks has been frantic primary market activity. Every single day, with very few exceptions, there has been a relentless flood of new corporate bond issues. Year-to-date supply has risen to around $970 billion and c. €310 billion in U.S. and European IG primary markets, respectively, thus exceeding by far new issue volumes over the same period in prior years.

From a bond investor’s perspective, roaring primary markets are both a blessing and a curse. On the one hand, as an incentive to buy, issuers offer their new bonds typically at more attractive valuations than their outstanding bonds. This new issue premium (NIP) can be substantial, particularly during times of market distress. Broker research reports have estimated the average NIP in March this year for U.S. and European IG markets at 25-40 basis points, which is a significant concession in the IG space. On the other hand, more attractive valuations in primary markets put considerable upward pressure on credit spreads in the secondary market, which hurts existing corporate bond holders, thus highlighting the double-edged nature of the new issue deluge.

Away from bond valuations, it is genuinely worrying for credit investors that so many companies are currently bingeing on gluttonous amounts of debt. Conventional wisdom has it that a bond issuer, when adding financial leverage through debt-financing, becomes more vulnerable, which in turn increases the riskiness of its debt instruments and puts downward pressure on its credit rating.

The new issue glut is also a profoundly bearish signal. What companies are effectively telling us is that they need to borrow money to boost their liquidity profile to compensate for precipitous revenue declines due to COVID-19. Needless to say, this is not a sustainable business model that can go on forever.

But elevated levels of primary market activity are not all bad news. In fact, I’d argue that the new issue frenzy is again a double-edged sword. Compared to ‘peak panic’ in the first half of March, when primary markets were essentially shut, the situation has undoubtedly improved. A functioning primary market, which is open for business and allows companies to raise capital to fund operating expenses and refinance existing debt, is a necessary condition to overcome the current crisis and the looming global recession. It is encouraging that even companies that are facing severe COVID-19 headwinds can tap into the primary bond markets to meet their current funding needs. Aircraft maker Boeing is the prime example, raising $25bn in the U.S. primary bond market at the end of April.

Ultimately, it all comes down to time horizons in my view. Over the short-term, high new issue volumes are a sign of market resilience. Primary markets are throwing companies a liquidity lifeline, which helps to keep default rates in the IG universe at very low levels and thus prevents a further escalation of the crisis. Over the medium- to long-term, however, many companies will emerge with significantly higher debt burdens. Some will be able to capture the economic post-crisis rebound and reduce leverage swiftly. Others will struggle with debilitating debt levels, though. Interest payments will absorb a fair amount of their future revenues, thus stifling their growth potential.

From a macroeconomic viewpoint, it also brings up the question of how many companies that would have otherwise disappeared given their weak balance sheets and poor productivity will survive based on readily available debt financing, thus circumventing Schumpeter’s famous ‘creative destruction’ principle. Is this a trend that is going to continue? That would mean lower innovative strength and subdued potential growth rates for developed economies going forward, which in turn could lead to difficulties to service debt burdens at some point down the line. It is always our job as active corporate bond fund managers to identify good and bad debtors, winners and losers, but in the post-COVID-19 era, this task seems set to become even more crucial.

James Carville was candidate Bill Clinton’s chief strategist for the 1992 election. When asked to emphasise the single most important issue to voters, Carville responded: “It’s the economy, stupid!” Incumbent President George W.H. Bush at that time had seen his poll numbers surge post the successful Operation Desert Storm in Kuwait, but at home the US economy had started to slip into a recession, and Carville made sure no opportunity was wasted to emphasise the ‘Bush recession’. Bush lost the 1992 election and followed in the footsteps of Jimmy Carter in 1980, who also lost in his re-election attempt against a backdrop of poor domestic economic performance. All Presidents who have sought re-election during periods of economic growth have easily secured their second terms; Reagan (1984), Clinton (1996), Bush II (2004), and Obama (2012).

A quarter is a long time in politics

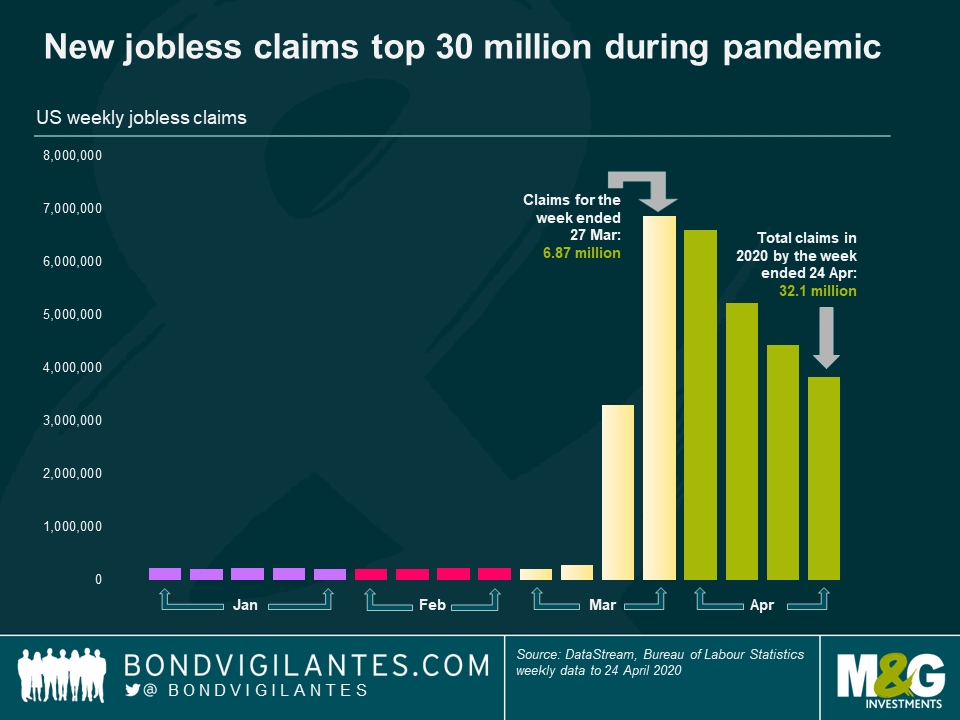

Up until January 2020, Donald Trump never let an opportunity go by without boasting how successful the US economy and the stock market had been during his term as President. Understanding how important a strong and growing economy is, as Carville did in 1992, Trump intended to use that as the springboard to a successful re-election campaign this November. Even with trade wars with China and the EU, he could show unemployment reaching a record low of 3.5%. However, three months is a long time in politics and much has changed. With the US economy in lockdown and unemployment numbers surging, Donald Trump is currently sitting on a unenviable position where the economy has net lost jobs during his tenure.

If history is any guide to the future, no president would ever be re-elected on these economic numbers.

The stable genius?

There are three main factors worth looking at to try and anticipate the November result:

- How will the US electorate view the Coronavirus? Will it be interpreted as an issue that the government should have foreseen and been better prepared for; or should it be looked upon as a natural disaster, where there is a patriotic effort to get through it and re-build the economy. By constantly holding China responsible, a country Trump had already accused of harming the US, the President will try and evoke unity against an external entity. Also, while their initial response to the pandemic was slow, the current administration will point out that they have taken decisive action on the economy and have poured out stimulus in record numbers.

- The re-start. Economies across the world have started slowly phasing out the lockdowns and restarting activities. The administration is eager to begin lifting restrictions to limit the increasing numbers of people who may find themselves permanently unemployed. If the population can see the economy improving again as we approach November and unemployment starts falling, then it will be favourable to Trump. The S&P index of the leading 500 US companies, which was down 31% at one point this year from historical highs, has recovered to now only being down in the single digits. If, however, the administration is seen as lifting the lockdown too early and there is an increase in cases or a second requirement for a lockdown, then that is likely to prove fatal for Trump’s re-election chances.

- The other candidate. Joe Biden is not the strongest candidate the Democratic Party has ever fielded. Prior to 2020 he has had two unsuccessful attempts at Presidential runs, one of which ended in 1987 when he was caught plagiarising a speech by UK Labour Party leader Neil Kinnock. Prone to his own verbal gaffes, and issues with his son’s involvement with Ukrainian and Chinese companies, Biden will not have an easy run. He still needs to convince the US electorate that he can be a strong and competent leader. Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton and Barack Obama had credible plans for how they would take the US economy out of the malaise when they sought office, Joe Biden will need a credible plan of his own.

Current polling, especially in the swing states of Pennsylvania, Michigan and Ohio looks favourable to Biden, but the preoccupation at this time is with the pandemic and not the upcoming election. Another factor we should not overlook is a President’s popularity with their base. Both Jimmy Carter and George W.H. Bush were challenged by members of their own party for re-nomination, none of the re-elected Presidents had a challenger. Donald Trump has not faced a credible challenger for the 2020 Republican nomination. Keeping the base loyal is very important for the election day turnout.

2020 has not been an ordinary year and will not see an ordinary US Presidential election. Many factors will come in to play as to whether or not Donald Trump is successful in his re-election efforts, but the economy will be the key issue. While the stock market is factoring in an economic recovery, in the next few months it will be crucial to see if the real economy does start improving rapidly enough.

* This blog first appeared on the Equities Forum