Navigating the crisis in frontier Asia: does a debt suspension make sense?

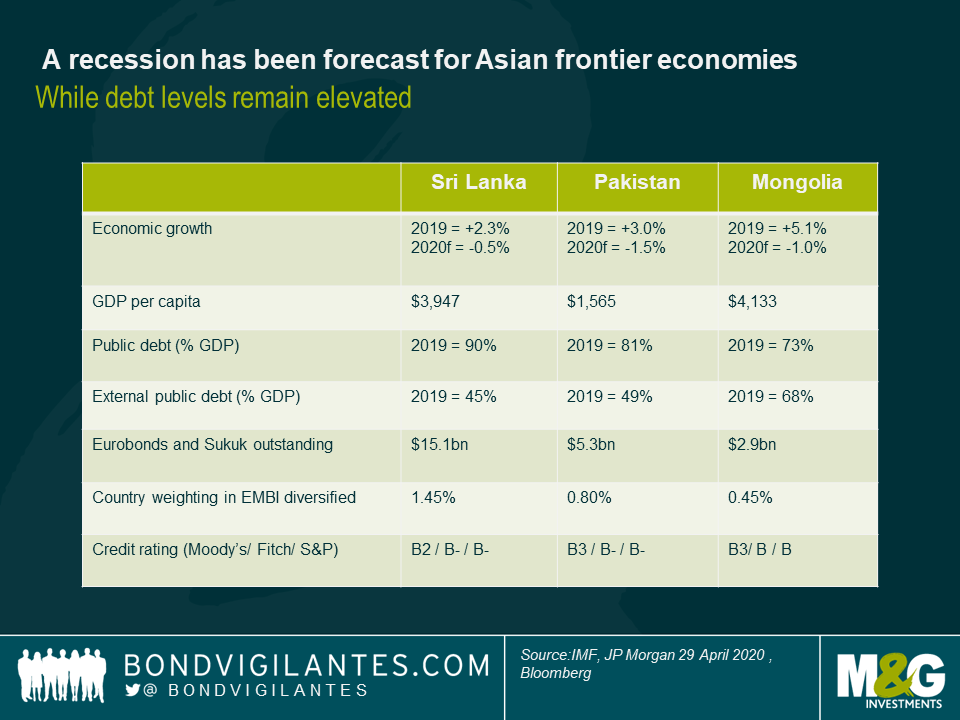

Sri Lanka, Pakistan and Mongolia have each been severely impacted by COVID-19, albeit in different ways. These frontier economies each straddle two worlds. They’re emerging markets in the sense they’ve had access to global debt markets, with their eurobonds included in JP Morgan’s emerging market bond index. But their credit ratings are far below those of investment grade sovereigns, such as Indonesia, who have already been able to issue eurobonds during the crisis. They also still attract significant official sector support as they still have sizeable development challenges. As recent recipients of concessional support from the multilaterals, they were deemed eligible among 70 other countries for the G20’s debt suspension initiative.

A time-bound debt suspension initiative

On 15 April, the G20 launched “a time-bound suspension of debt service payments for the poorest countries that request forbearance”. Questions about this initiative have included: Which countries will be involved? Which creditors will be involved? Will it be considered a default? And how will it all be implemented in practice?

On the creditor mix the G20 stressed that: “all bilateral official creditors will participate in this initiative, consistent with their national laws and internal procedures”. This implied that China – a G20 member – was onboard. The Paris Club has for several decades been the medium for bilateral debt relief but, because China is not in that club, G20 leadership was crucial. The language for multilateral participation was weaker: “We ask multilateral development banks to further explore the options for the suspension of debt service payments”. And regarding commercial debt the G20 said they “call on private creditors, working through the Institute of International Finance, to participate in the initiative on comparable terms”.

Since then, the onus has been on eligible countries to choose whether or not to participate, and to what extent. Most eligible countries have not made public statements about the scheme, but some have confirmed their intention to participate. The Prime Minister of Pakistan and President of Sri Lanka have both publicly pledged their support for the debt moratorium.

Pakistan

The government has been working to bring the pandemic under control. As is the case globally, the radical uncertainty makes GDP predications unusually uncertain, but the IMF has forecast a -1.5% decline in growth in 2020. This would be the country’s first contraction since the 1950s, even though fiscal stimulus has been provided and monetary policy eased in response to the crisis.

The country’s resilience has been supported by pre-crisis reform efforts, made under an IMF programme. This made it easy for the official sector to scale-up their support quickly, including $1.39 billion of emergency financing from the IMF. As an oil-importer, lower global prices for oil have helped cushion the trade balance. But the global crisis is still putting pressure on the balance of payments in 2020, with the biggest hits from reduced remittances and portfolio outflows.

Half of Pakistan’s public external debt service requirements over the next year are to non-Paris club bilateral creditors, with China, Saudi Arabia and UAE by far the largest creditors. A further 20% is owed to the multilaterals, and 25% to commercial creditors. Regarding a debt service suspension, Pakistan recently clarified that it is talking only to bilateral creditors, where its immediate debt pressures are. Despite the clarification that private creditors would not be approached, Moody’s put their B3 rating on a negative watch, in case private creditors are forced to participate on comparable terms.

Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka is also facing a recession in 2020, following its necessary response to the virus, reduced tourism, remittances and trade. For example, apparel and textile exports fell by 41% in March and tea exports halved.

The pandemic is aggravating economic vulnerabilities that pre-date COVID-19. The economy suffered from a number of recent shocks and political volatility delayed much needed reforms. Having put off a shift to fiscal prudence, Sri Lanka’s public debt climbed to 90% of GDP in 2019.

While Pakistan got rapid emergency financing from the IMF, Sri Lanka’s request could not be met as quickly. The current IMF programme, scheduled to end in June 2020, required the Sri Lankan government to increase revenue to place public debt on a downward path. But pre-crisis, in anticipation of the election scheduled for early 2020, there were tax cuts. The IMF programme had previously made waivers for missed fiscal targets and would need assurances about the future fiscal path. So a discussion is needed on future IMF support, which is crucial for investor sentiment, but this is tricky conversation to have prior to the election.

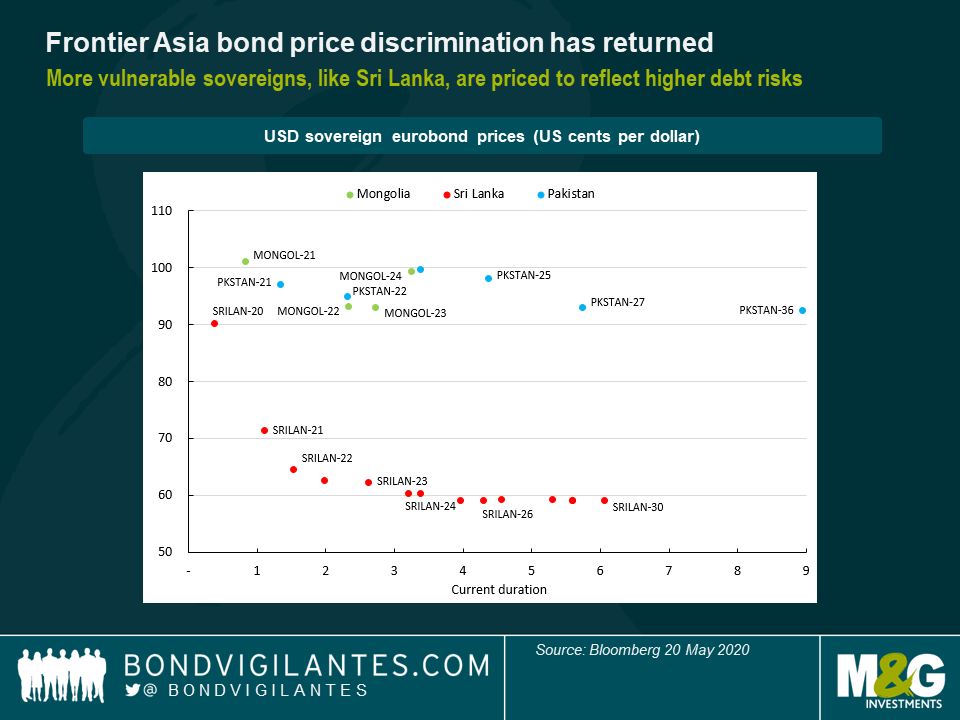

Sri Lanka was going to issue eurobonds in 2020, but since the start of the crisis its spreads have soared into distressed territory. The markets are currently pricing a good probability that the $1 billion eurobond, due in October 2020, is paid. But there is clear doubt to whether Sri Lanka will be able to turn things around over the next few years and remain current on its debt.

In response to such concerns, on 19 May 2020, Sri Lanka’s central banks made a statement “that Sri Lanka will duly honour all its debt service obligations in the period ahead”. Priced out of the eurobond markets the government said it was “exploring bilateral and multilateral sources, plus SWAP facilities with regional central banks” that include India, plus the possibility of syndicated financing to bridge the gap until market sentiment improves. Little mention has been made of debt suspension since the President had encouraged it in April. The next day S&P downgraded Sri Lanka to B-, but did not make any mention of debt suspension in their press release.

Mongolia

As of 20 May 2020, Mongolia had recorded 140 cases of COVID-19 with no related deaths. Despite the reported success in containing the virus’ spread from China, the economy has still been hurt, mostly because it is heavily dependent on export revenue from copper, gold and coal.

Like Sri Lanka, securing emergency financing has been harder than for other countries. Mongolia’s IMF programme lapsed in 2019 and discussions on a new set of medium-term reforms, needed to stabilise debt risks, had been put off until after the Mongolian elections scheduled for mid-2020. Nonetheless, the IMF has signalled that emergency financing will eventually be made available, even if discussions on future engagement take longer.

Mongolia has managed to reduce public debt to 73% GDP in 2019, from 88% GDP in 2016, but the crisis has halted this trend towards improved debt sustainability. Like in Pakistan’s case, its bonds are currently trading at levels that suggest market access is not an immediate option but, if market sentiment continues to improve for frontier markets, it might soon return as an option.

Does a debt suspension make sense?

The COVID-19 crisis has clearly worsened the debt metrics of Mongolia, Sri Lanka and Pakistan. But not ruinously so to date. This suggests that approaching private creditors at this point for a debt suspension would be a mistake. It risks further credit rating downgrades, and years of hard won market access might be eroded. Access to capital will be needed between 2021 and 2024 to finance development and for refinancing, so that the countries can stay current on their debts. If a suspension could be limited to some reprofiling of bilateral debt then the burden might be eased in 2020 without damaging credibility. Moody’s reaction to Pakistan’s bilateral debt suspension request suggests caution is still needed here however, as there remains uncertainty about whether comparable treatment will be demanded from other creditors. Eurobond pricing for Mongolia and Pakistan looks to reflect a market view that they will not default. However, eurobond pricing for Sri Lanka sits in a wait-and-see area, as investors make their minds up about whether or not they think further trouble is ahead.

For the poorest countries without market access, it makes good sense to push for as much debt relief as possible. There is no market access to lose. But for countries who have established themselves in the markets, a hard decision is needed, which must be based on the country context. A blanket approach to debt suspension is therefore best avoided: in some circumstances, it will make the crisis worse, by adding a debt or financial crisis to the already severe health and economic impacts of COVID-19.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

17 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox