“Events, dear boy, events”, UK Prime Minister Harold Macmillan responded to a journalist when asked what is most likely to blow governments off course.

At the beginning of this year, Donald Trump was favourite to follow in the footsteps of the previous three Presidents and win re-election. However, events have since unfolded that put his re-election into serious doubt.

Polling

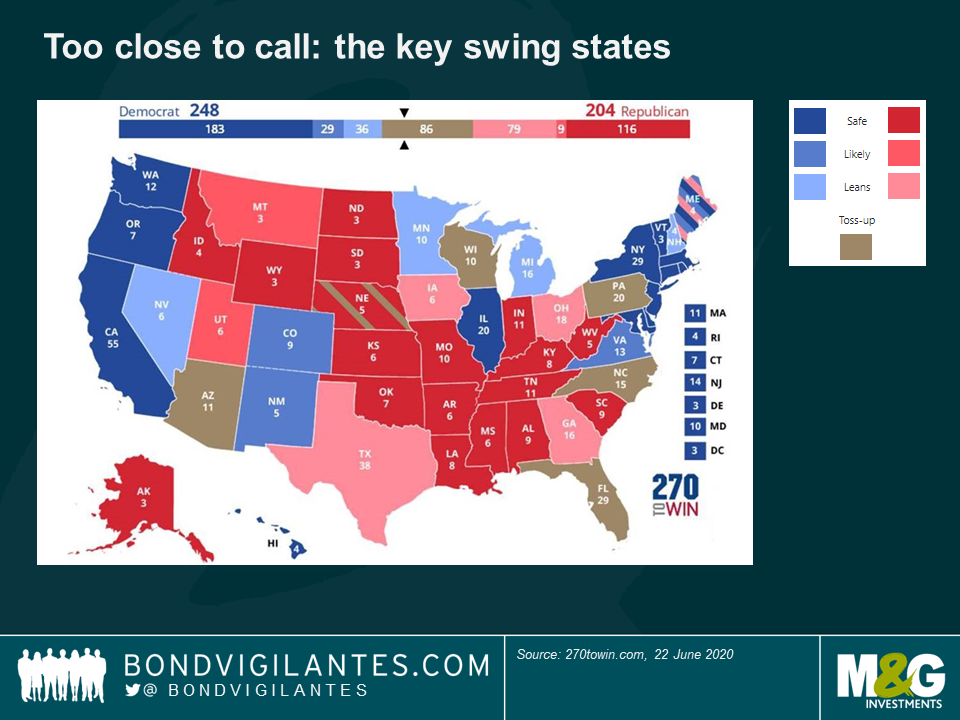

The Democratic candidate Joseph Biden is ahead in every single national poll by wide margins, polling well outside the margin of error. The swing state polling is much closer, but it still looks favourable to Biden right now.

We need to factor in that most polls in 2016 gave Hillary Clinton a commanding lead, which did not materialise on election day. Given the unrest at the moment, this may be due to ‘shy Republicans.’ The election is still likely to be close. The latest Zogby poll of “Who do you think will win?” rather than “Who will you vote for?” gave Trump a 51%-43% lead.

The Electoral College

The US election is not won by a popular national vote: instead the candidates need to win the election state by state. Each state then gives its electoral college votes to the candidate who obtains the most popular votes within that state. Trump flipped Pennsylvania, Ohio, Florida, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Iowa from the Democrats in order to win in 2016. He has smartly registered as a resident of Florida (from New York) for the 2020 election as he knows how important the state is for his re-election. Without it he will be a one term President.

Trump will likely hold Ohio and Iowa. Assuming he keeps Florida, that means he needs to hang on to one of the other three states from the above list. The mid-western state of Wisconsin right now looks like the place he needs to focus his efforts. He also needs to keep hold of Arizona, Georgia and North Carolina, all of which he won in 2016. All are traditionally Republican states but are looking close in polling. Arizona will be the state to watch. As Arizona goes, so will the country.

US election of 1968 again? – Hubert Humphrey vs Richard Nixon

The social unrest due to the Vietnam war and the ‘free love’ movement all culminated in a narrow win for the not-so-popular Richard Nixon in 1968. Nixon later said “the silent majority” had spoken: the Americans who don’t necessarily speak out, but who were unhappy with the direction of the country.

The current social unrest could be a test for Democrats. If the party shifts too far to the left it will be problematic for them. The “Defund the Police” movement will scare a lot of swing voters (with some polls showing 7 out of 10 African-Americans are against it). Democrats needs to be careful they are not captured by this.

Gun sales in May reached a high of 1.8m! That’s a lot of worried voters. Biden seems to be countering this with a strong pick for vice-president, with the short-listed candidates having strong law and order backgrounds.

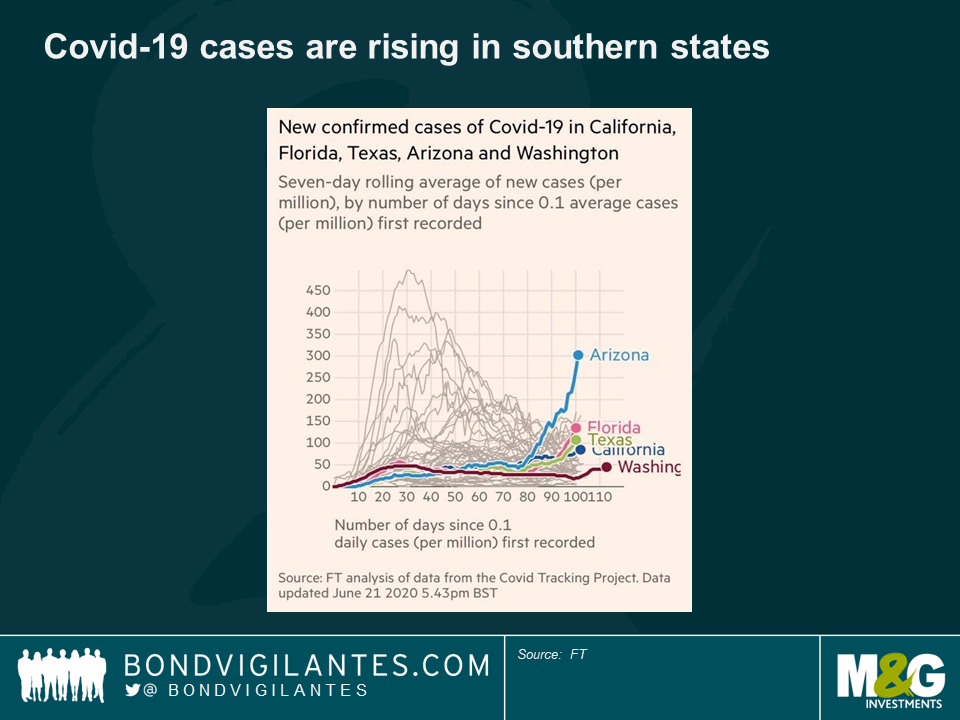

Covid-19

There are now concerns over a second shutdown, with the Coronavirus infection rate rising in southern states. This could stall the momentum the economy has (the unemployment rate unexpectedly fell in May to 13.3% from 14.7% in April). Trump needs this momentum to continue if he has any chance in November.

A recent poll showed that Trump still had a 95% approval rating amongst Republicans. This is very important. Carter and Bush Snr lost their re-election attempts when they lost the base of their own parties. Republicans are discussing another stimulus package, but this will not be easy to get through the senate. Hawkish senators will balk at yet more government spending and adding even more to the national debt. Trump may need it to get the economy through until November.

Policy

Trump wants out of the Paris Climate deal, but in effect the winner of the next election will decide. Joe Biden, who is more of an internationalist, will keep the US in. Expect a Green New Deal if Biden is elected, plus an increase in social spending.

Spending in general will go up under Democrats, so we should expect some pressure on US Treasury yields then. I think it is safe to assume that, if Joe Biden does win the November election, the Democrats will keep their majority in the House of Representatives and also re-capture the Senate. A single party holding both chambers and the White House will not have too much trouble passing legislation.

It is worth remembering that Joe Biden is not the self-styled Democratic-Socialist Bernie Sanders is – there will be no revolution. So financial markets should be relatively stable. Democrats tend to talk about offsetting spending with tax rises. US corporate tax rates would likely be restored to the Obama era level. Fuel tax rises would also be increased to help pay for the green new deal.

From a UK perspective, Trump is the most Anglophile holder of the office since the last elected US President from New York, Franklin Delano Roosevelt. As we are now leaving the European Union, a trade deal with the US will be very important and can be used as leverage to sign deals with other countries around the world, including the EU. The Trump administration so far has shown itself to be accommodative.

Biden/Running mate

Biden is four years older than Donald Trump. There is a chance he will commit to only one term as President. His pick of vice president will be important. It is likely to be an African American woman, with Kamala Harris (former prosecutor and California Senator) or Val Demmings (former chief of police and current Congresswoman from Florida) as favourites. Both seem sensible and uncontentious choices, but have shown tendencies of being politically naïve.

Biden will need to prove that he can be strong against foreign adversaries, especially China. It was the China rhetoric that helped propel Trump to the White House in 2016 and win over the traditionally Democratic mid-west and rust belt states.

This is Joe Biden’s third attempt at the Presidency (the first was in 1987). He lacks the political instincts of Donald Trump, Barack Obama, or Bill Clinton. The fact the candidates are unable to campaign fully right now works in Biden’s favour. But it is unlikely to stay this way until November.

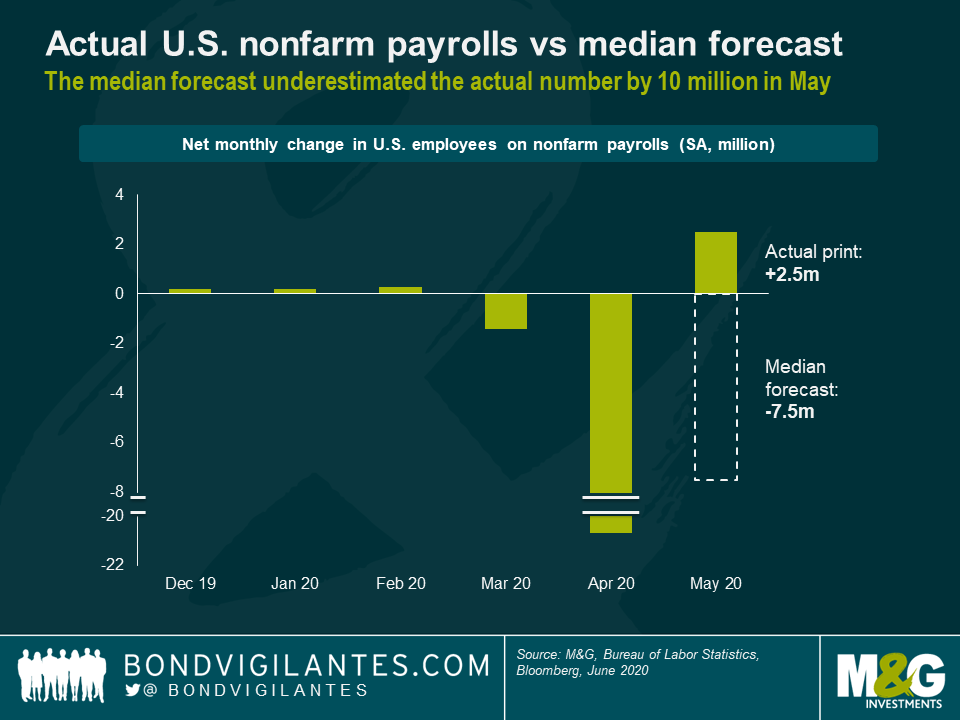

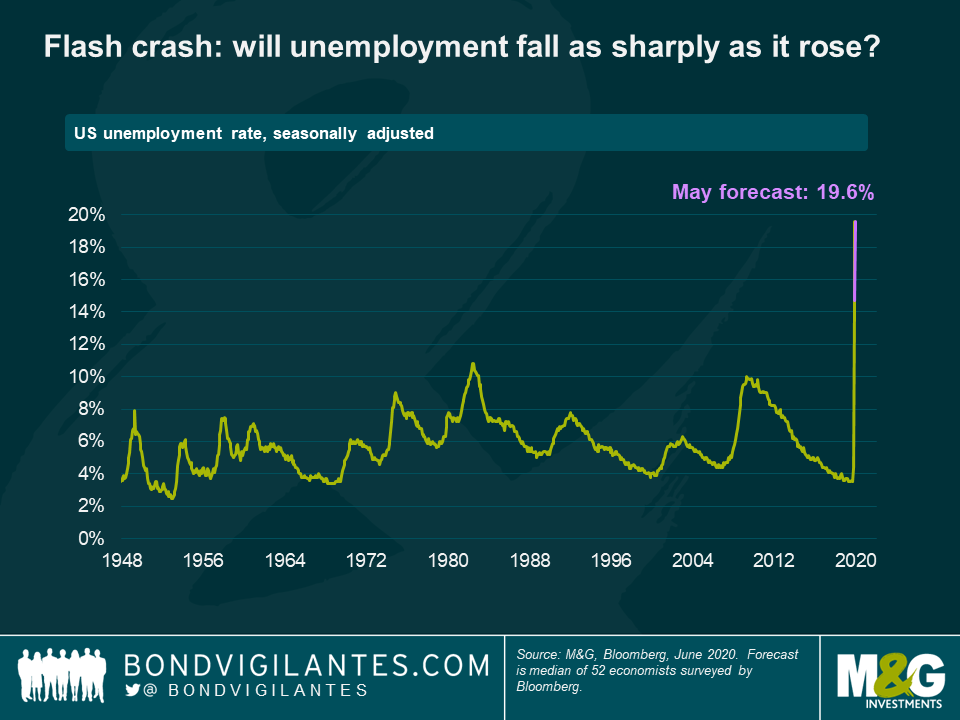

Wowsers, the U.S. labour market never ceases to amaze bond investors. After the cataclysmic April U.S. employment report—nonfarm payrolls (NFP) had dropped by 20.7 million and the unemployment rate had shot up to 14.7%—there was broad agreement amongst market observers that May would prove to be another challenging month. In a Bloomberg survey of 78 economists, the most bullish forecast was a NFP decline of 800,000. The median NFP projection indicated a loss of 7.5 million jobs, while the unemployment rate was predicted to approach Great Depression levels of around 20%.

But—surprise, surprise—the unemployment rate actually fell to 13.3% as the U.S. labour market added a record 2.5 million jobs in May. This means that the median NFP survey forecast was off by a whopping 10 million, a truly spectacular miscalculation. How could this happen? How could so many esteemed economists fail to predict the resurgence of the U.S. job market? Pundits were quick to point to misleading jobless claims data and an underappreciation of the effects of the U.S. government’s relief measures. But I think the real issue is more fundamental. The COVID-19 induced economic downturn is in many ways uncharted territory. The unprecedented nature of the crisis calls into question the applicability of standard economic models.

As bond investors we therefore have to come to terms with elevated levels of uncertainty. Friday’s U.S. employment report wasn’t the first macroeconomic surprise of late—albeit the most remarkable one—and in all likelihood it won’t be the last. Needless to say, unexpected economic data points do move markets. On Friday, driven by U.S. job data, the 10-year U.S. Treasury yield jumped up by nearly 10 basis points (bps) while the spread level of CDX HY, a bellwether of U.S. high yield credit risk, collapsed by nearly 50 bps. This increases the risk of investors being caught on the wrong foot. Considering the ultra-low levels of core government bond yields and the strong recovery in credit markets over the past two months, the margin of safety isn’t particularly generous. Hence, in my view, it is prudent to avoid an overly directional portfolio positioning and balance risk exposures instead.

Furthermore, while Friday’s employment report was certainly a highly encouraging testament to the resilience of the U.S. labour market, investors should be careful not to give the all-clear prematurely. There are still 21 million unemployed persons in the U.S., plus another 9 million not in the labour force who currently want a job. A further 10.6 million classify themselves as employed part time for economic reasons. It will take time for the U.S. labour market to shake off the devastations of COVID-19. There is a risk that investors get overly optimistic, pricing in a frictionless V-shaped recovery, which could lead to disappointment and adverse market reactions. And while markets are fixated on COVID-19, we shouldn’t forget that it is not the only obstacle to economic growth. Trade tensions between the U.S. and China—the bogeyman of 2018—have been building up in the background. Further escalation might damp the speed of economic recovery.

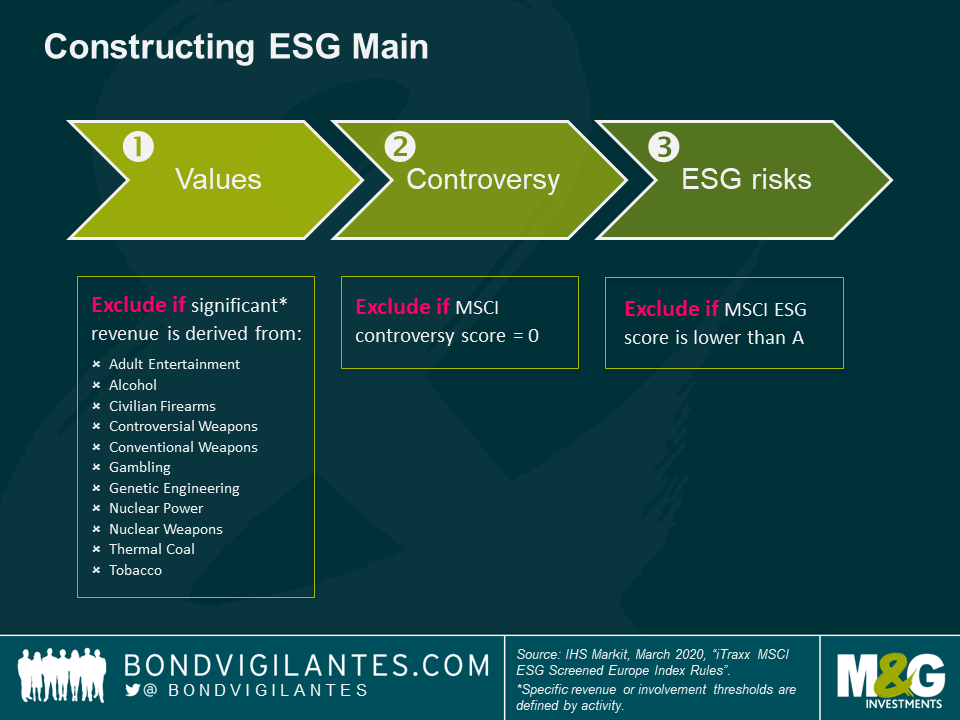

This month will see a significant step forward in the evolution of ESG (environmental, social and governance factors) as a part of fixed income investing, with the launch of the iTraxx MSCI ESG Screened Europe CDS (credit default swap) index. The past few years have seen a noticeable acceleration in investors’ ESG awareness, driven to varying extents by social conscience and evidence that ESG factors provide a useful framework in fundamental company research. One of the challenges for wider integration is the availability of information, and the ease with which investors can act on it. The launch of the new index will help in both these areas. But even if you don’t count yourself as an ESG investor, the launch of the new “ESG Main” index brings some important considerations:

- A wider opportunity set for relative value (RV) trading;

- The ability to trade “Non-ESG Main” by entering into a long-short position between the Main index (“the Main”) and ESG Main;

- Better access to ESG information, and better ability of credit market participants to act based upon it, will make ESG more important as a Factor (i.e. investment style).

More on these below – first, how is the new index made up?

Credit investors finally show up to the party

There are currently many indices and ETFs giving equity investors access to ESG information and ESG-based trading, but credit investors have come later to the party. While a number of research providers like MSCI provide ESG factor-based analysis of many corporate credits, until now there has been no liquid, tradeable ESG credit index security.

The iTraxx Main index already allows investors to gain long or short exposure to the risk and return profile of a basket of 125 of the most liquid CDS referencing underlying European investment grade bonds, and attracts trading volumes close to €1.5 trillion a year¹. The new ESG index will be an exclusion-based version of the Main, and will start trading from 22 June 2020 at the five year tenor. Starting with the equally-weighted Main, the ESG index is constructed by a three-step screening methodology².

First, a values-based screen if applied. Any issuer which breaches specific thresholds of revenue derived from activities including alcohol, weapons and thermal coal is excluded. Second, any company exposed to major controversies (measured by adherence to certain sustainability and social responsibility principles, such as the United Nations Global Compact and International Labour Organization conventions) is excluded. The final step considers the issuer’s resilience to long-term, financially material ESG risks (is it at risk of regulatory penalty due to environmental damage? How sustainably does it treat the communities in which it operates? Does it have appropriate risks and controls in place to ensure directors act in shareholders’ and creditors’ best interests?).

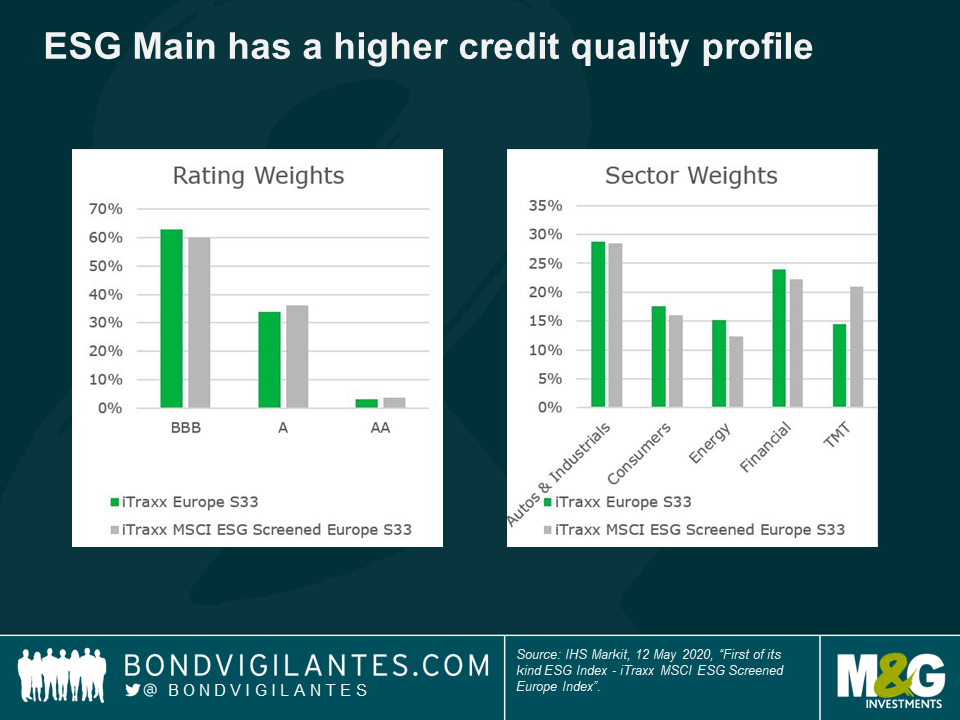

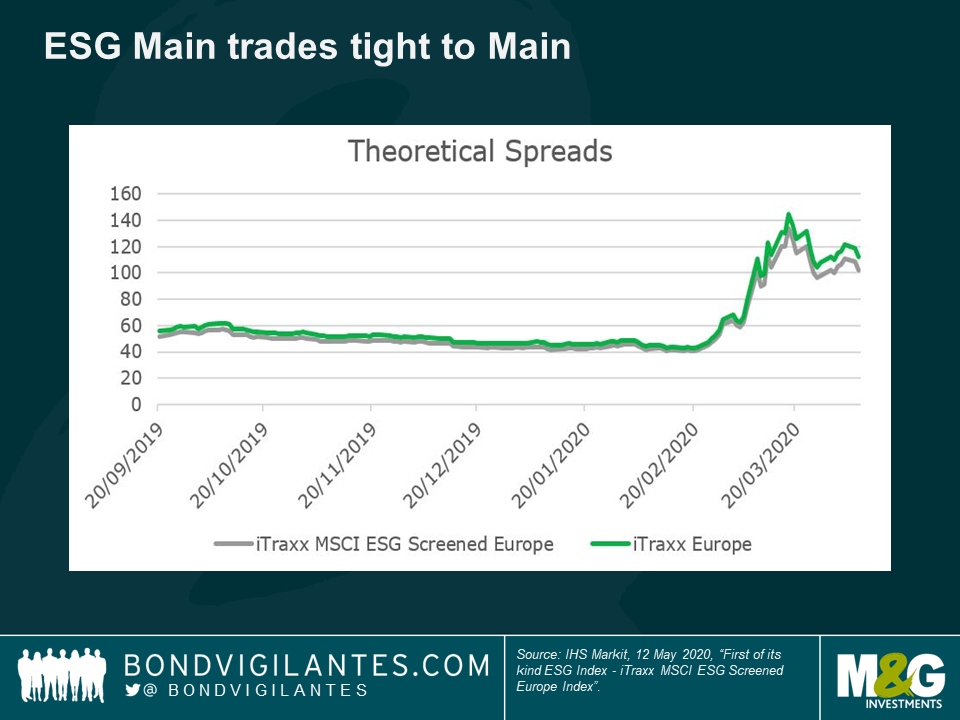

The profile of the resulting basket is what you might expect, with a higher credit quality bias and trading (using backfilled data) at a slightly tighter credit spread than the Main. Interestingly, the exclusions result in an overweight to TMT in the ESG index and an underweight to other sectors, including financials.

For ESG funds, the new CDS contract will offer an easier way to enjoy the benefits which other CDS indices confer: principally liquidity, lower trading costs than physical bonds and the ability to add or remove risk exposure to a basket of credit easily. But even if you don’t currently consider yourself an ESG investor, the arrival of the new index will still have implications.

Three things to consider, even if you’re not an ESG investor

1. Relative value trading

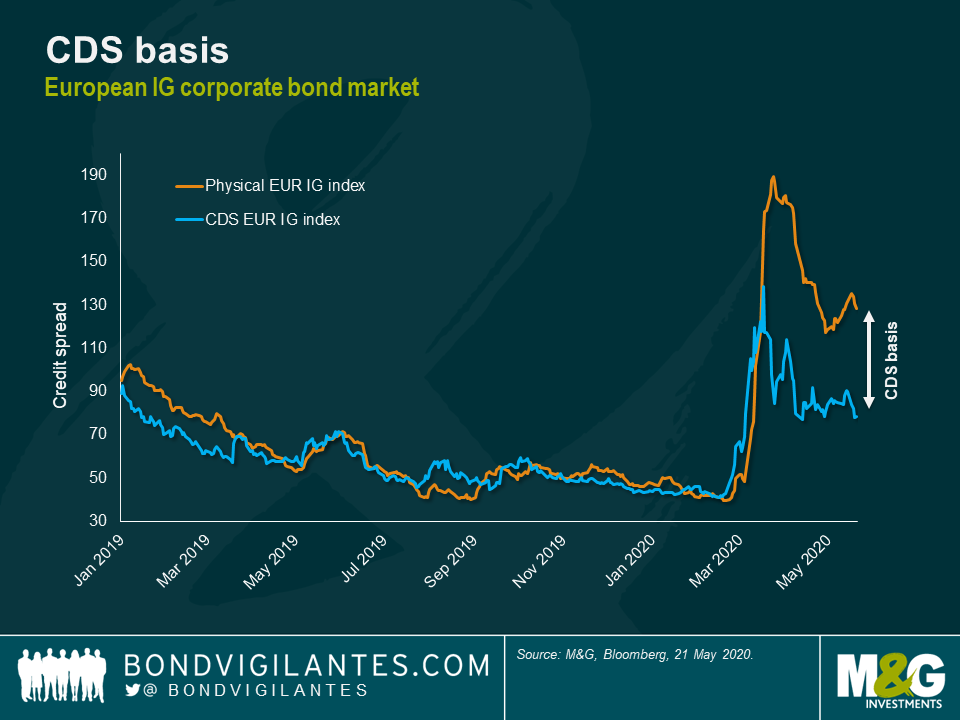

CDS indices already offer investors opportunities to enter relative value trades, firstly between derivatives and the physical securities they reference, and also inter-derivatives (i.e. between the index and individual swaps). For example, spreads offered by physical corporate bonds are currently significantly higher than those available through taking CDS exposure, the result of CDS attracting a high liquidity premium in the current environment, and of excess supply in the physical primary market. The new index will increase the opportunity set available to take advantage of such dislocations.

2. Trading Non-ESG Main

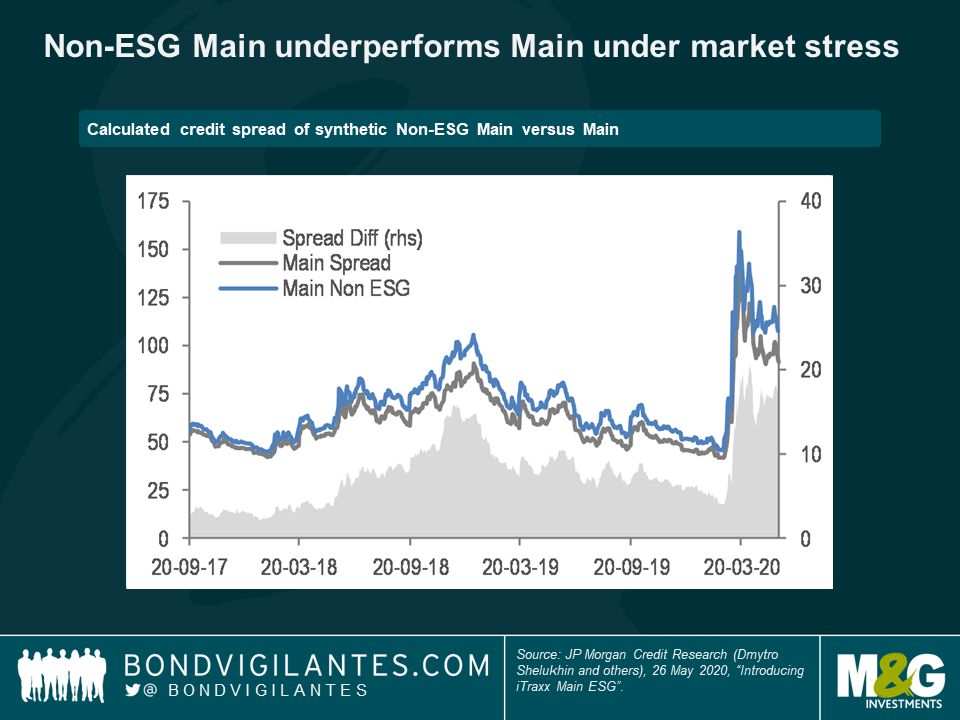

The ability to enter into risk-additive or -subtractive trades in both the ESG and Main indices will allow investors to take a long or short position on a Non-ESG Main index (i.e. to modulate their exposure to the issuers excluded by the three-step screen). This has a variety of use cases. For investors who want to buy CDS protection during times of market stress against ESG laggard names they own, a buy-protection Main, sell-protection ESG trade would achieve this exposure. Likewise, investors may wish to take the other side of this trade to gain exposure to a higher beta investment grade credit instrument with a spread pick-up.

While the ESG index is not yet tradable, calculations by JP Morgan³ of an historical spread (based on the current series 33 basket of included names and backfilled to the September 2017 series 28 roll), reveals that such a synthetic Non-ESG index exhibits underperformance against the Main in times of market stress, while the ESG index outperforms. Based on this time period, the ESG index had a very similar return profile to the Main but with lower volatility and a slightly better drawdown profile in bear markets.

3. Wider access to information and ESG profile-raising

Aside from these more tactical trading opportunities, the launch of the ESG index has a wider implication for all investors. Without a structure against which to consider E, S and G factors, the concept can seem quite esoteric and is hard to quantify. But with growth in the concept which began with the standardisation of data by MSCI and other providers, and has now reached the formation of a tradeable corporate credit index, ESG is a lot easier to nail down as a Factor. It will also be interesting to see if this develops further over the coming months, for example with the launch of an ESG high yield index (which, given the underlying issuer profile, would presumably require less restrictive exclusion thresholds in order not to become overconcentrated).

More transparency and easier trading will make ESG more important as a Factor

The logic of considering the individual ESG risk factors aside, the very fact that market participants will now be better able to act on this new Factor makes it important to consider—whether you think of yourself as an ESG investor or not. The greater liquidity and transparency offered to the market by the index will also make it easier to assess the relative risk-reward profile of ESG credit investments over the longer term. And there is a case to be made that this will lead to ESG outperformance becoming something of a self-fulfilling prophecy—much the same argument as one could apply to technical analysis. Some of these trends, which may have begun for equity investors, have now arrived for corporate credit. Whatever your approach to the new ESG CDS index, its launch this month will be worth watching.

¹ ISDA SwapsInfo, Accessed 1 June 2020, [http://swapsinfo.org].

² IHS Markit, March 2020, “iTraxx MSCI ESG Screened Europe Index Rules”; IHS Markit, May 2020, “First of its kind ESG Index – iTraxx MSCI ESG Screened Europe Index”.

³ JP Morgan Credit Research (Dmytro Shelukhin and others), 26 May 2020, “Introducing iTraxx Main ESG”.

We are currently in the throes of the sharpest and largest economic downturn the modern global economy has ever seen. However, as I wrote in March this is very different from previous recessions.

To recap, a recession has three stages:

Stage 1: into recession

A rapid, record collapse in economic growth as normal economic life is dramatically curtailed for public health reasons.

Stage 2: end of recession

A rapid. record jump in economic growth as we lift public restrictions.

Stage 3: post recession

An economy trying to offset new business practices and a collapse in confidence with strong monetary and fiscal stimulus.

Where are we now?

Economic growth has plunged, unemployment has soared, and we are now at an inflection point, at which growth will now be rebounding and then eventually settling on a relatively (to 2020) stable course: as I wrote in my last blog, a Flash Crash t-shaped recession.

Unlike previous recessions, we can understand and explain the timing of stages 1 and 2, as they are a direct result of a simple government policy. Unlike previous recessions, stage 3 will be outside of normal textbook thinking. Indeed, according to textbook economics, are we actually going to have a recession? Bizarrely, the Flash Crash in economic growth means that, from one point of view, this collapse in economic growth may not even be defined as a recession.

The widely-accepted definition of recession is two successive quarters of negative GDP growth. Based on calendar quarters, we will meet the recession criteria easily in 2020, with negative growth in the first and second quarter. If I were to be especially pedantic however, on a rolling quarterly basis the recession definition will simply not have been met. If we assume that full lockdown started on the 1st of March and ends on the 31st of May, then we will have the first negative quarter of growth we need over this three-month time frame. However, we know that the subsequent quarter, from 1st June till the end of August, will be one of record economic growth. Therefore, on a rolling basis, we will not have generated a recession by the end of August. Given the rapid collapse-and-bounce-back nature of this economic slowdown, should it be defined as a recession at all?

Returning to my original blog, this is why the collapse and recovery looks like a t. It is clear that total economic output will be lower at the end of August than the start of the year, with huge consequences. The question for 2020 and beyond is: how high is the bounce to where we draw the horizontal line of the t?

Governments and fiscal authorities around the world have thrown a record amount of fiscal and monetary response at the problem in an exceptionally short time frame. To modify a famous phrase, the authorities’ job has not been to take the jug of alcohol away from the party, but to facilitate one almighty happy hour. While this hair of the dog policy will not fully cure the hangover, the question is: how much will it cure it? This is where we come back to stage 3.

Fiscal and monetary authorities will understandably want to return the economy to its past glories, which suggests we will see continued fiscal and monetary easing. This will conflict with virus-related changes in business practices, and the extent to which individuals’ behaviour (consumer confidence) is altered by this year’s experience. The authorities will continue providing the stimulus antidote to the lockdown programme, fighting against the progress (or hopefully lack of progress) of the virus, and the damage done by such a short, sharp shock and economic downturn to business, consumers and governments.

It’s been a wild ride in May for Italian government bonds, so-called Buoni del Tesoro Poliennali (BTPs). The yield spread of 10-year BTPs over 10yr German Bunds first rose to c. 250 basis points (bps) after the German Constitutional Court had ruled that the ECB’s Public Sector Purchase Programme (PSPP) was partly unconstitutional. Subsequently, the Italian risk premium collapsed to c. 190 bps when the COVID-19 situation started easing and details around the proposed EU recovery fund were unveiled. European bond investors are scratching their heads about the direction of travel for BTPs, going forward. In my view, we have to take into account three key aspect—the Good, the Bad and the Ugly.

The Good: Next Generation EU

Clearly, the European Commission’s plan to launch ‘Next Generation EU’, a €750 billion EU recovery instrument, is excellent news for the European periphery and especially Italy. The proposal combines joint borrowing at the European Commission level with the provision of grants and loans to the regions and countries most affected by COVID-19. The European Commission went above and beyond what many political observers had previously considered possible by clearly prioritising grants over repayable loans. In fact, two thirds of Next Generation EU funds, i.e., €500 billion, would be distributed in the form of grants. Italy alone would receive more than €80 billion in Next Generation EU grants, more than any other country.

Beyond immediate crisis relief, Next Generation EU could have more far-reaching implications. Many a commentator enthusiastically referred to the Merkel-Macron plan for a grant-focused EU rescue fund, on which Next Generation EU is based, Europe’s seminal ‘Hamilton moment’. If this is the case and the EU really moves towards fiscal integration, we should expect yield dispersion in the Euro area to drop sharply. In this scenario, BTPs are very likely to perform particularly well. With the exception of Greek debt, Italian BTPs are currently trading at a higher risk premium over Bunds than any other Euro area government bonds—more than 90 bps wider than Spanish bonds at the 10-year point, for example—thus offering a greater potential for spread compression.

In my view, there is considerable downside risk to the BTP compression trade, though. So far, Next Generation EU is just a proposal, albeit a bold one, which still requires support from EU member states. It is entirely within the realms of possibility that the plan is watered down, delayed or scaled back in the process. In fact, Austria, the Netherlands, Sweden and Denmark—the so-called ‘frugal four’—have already presented a counter-proposal, based on repayable loans rather than grants. Chancellor Merkel, one of the architects of the proposal, is also facing headwinds at home, not least within her own party. One of the key points of criticism is that allowing the European Commission to borrow €750 billion on behalf of the EU to fund Next Generation EU could be construed as European debt mutualisation through the back door.

The Bad: Italy’s economic outlook and debt burden

Even if Next Generation EU is implemented as planned, it could turn out to be merely a one-off measure rather than a Hamiltonian watershed moment ushering in a new era. If in the end European fiscal integration proves elusive, Italy’s Next Generation EU boost might be short-lived and markets are likely to shift their focus rather swiftly back to the country’s fundamentals, which do not give occasion to overwhelming optimism. Even before COVID-19 struck, economic growth in Italy was anaemic. The economy already contracted in the final quarter of 2019 by 0.2%. The latest quarter-on-quarter GDP print (-5.3% in Q1 2020) is concerning and distinctly weaker than for the Euro area as a whole (-3.8%). According to a recent Bloomberg survey amongst 32 economists, the Italian economy is expected to shrink by 10.3% this year.

And while 2020 is going to be a highly challenging year for most economies, what makes the situation particularly precarious for Italy is the country’s high debt burden. According to Eurostat, Italy’s government debt-to-GDP ratio is close to 135%, which is more than 50 percentage points higher than the Euro area average (84.2%). Taking into account the Italian government’s recently announced €55 billion stimulus package, in combination with the shrinking GDP base, the EU Commission expects Italy’s public debt to jump to nearly 160% of GDP this year, a whopping 100 percentage points above the maximum debt level stipulated in the Maastricht Treaty.

So far, the prospect of Italy’s government debt rising to eye-watering levels has not spooked investors. One of the key factors is clearly the ECB’s ultra-accommodative monetary policy stance. The €750 billion Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) in particular carries weight. Unlike the PSPP, the PEPP gives the ECB a fair amount of flexibility to tilt purchases of public sector securities away from the capital key of the national central banks. When push comes to shove, the ECB could ramp up BTP purchases, thus providing a backstop and calming markets, at least temporarily. Over the long-term, however, I don’t think central bank support alone is going to be a panacea to Italian indebtedness. Unless a credible path towards pan-European fiscal integration emerges, bond markets are likely to call into question the sustainability of Italy’s debt burden at some point.

And the Ugly: Italian politics

One important risk factor around BTPs, which is currently neither debated much nor priced in, is politics. Granted, the situation seems less fragile now than at the beginning of the year, when Eurosceptic opposition party Lega was above 30% in opinion polls. Since then, Lega support has dropped by around 5 percentage points, while Italy’s government coalition has closed ranks and prime minister Conte’s approval ratings have soared.

Growing support for the current leadership in a moment of crisis isn’t unusual, of course. The question is, how long will it last? Chances are that as soon as the nature of the crisis shifts from public health to economic depression, Lega and other opposition parties will gather steam again. Especially in case pan-European crisis responses falls short of expectations, anti-EU political forces would have plenty of verbal ammunition to pull in votes. A number of regional elections, taking place later this year, will be an important litmus test. Investors only have to look back two years in order to remind themselves how sensitive BTP valuations are to political risk in Italy. In May 2018, BTP yields jumped from 1.75% above 3% in a matter of weeks when a coalition government involving Lega took shape and anti-EU rhetoric was dialled up.

Conclusions

Undoubtedly, BTPs have a lot going for them right now. The Next Generation EU proposal has evidently boosted investor confidence in the European periphery. And many market participants expect that the ECB is going to announce later this week an expansion of PEPP purchase volumes by €500 billion, which would be another tailwind for BTP valuations. Hence, it is entirely possible that BTPs spreads continue to compress, at least in the short run. However, medium to long-term I remain very cautious. Without ever deepening pan-European fiscal integration, which may or may not happen, BTPs are very likely to come under considerable pressure again due to Italy’s economic malaise, its towering debt burden and political fragility. In my view, at a spread of c. 190 bps over Bunds investors might not get adequately compensated for the lingering risks.

Summer has arrived, and so should the main tourist season in Europe in a normal year. However, as we know, this year has been anything but normal. With lockdown endings in sight across the majority of countries in the region, most are preparing to welcome tourists back. Some have already opened their borders for EU visitors, while many prepare to open them for everyone from late June or early July. When and whether tourists actually return though is quite another question. Despite the removal of travel restrictions, many people will likely still limit their travel due to safety concerns and significant drop in their incomes.

Some of the first hard data since the beginning of the pandemic have not been encouraging – for example, Turkey has reported 99% y/y drop in foreign tourist arrivals in April. On a positive note, for the vast majority of European countries, the highest share of tourist revenues tends to come in Q3 (up to 50-60% of the annual total). Consequently, in theory there is still some time partly to make up for the losses in April-June, provided willingness to travel recovers.

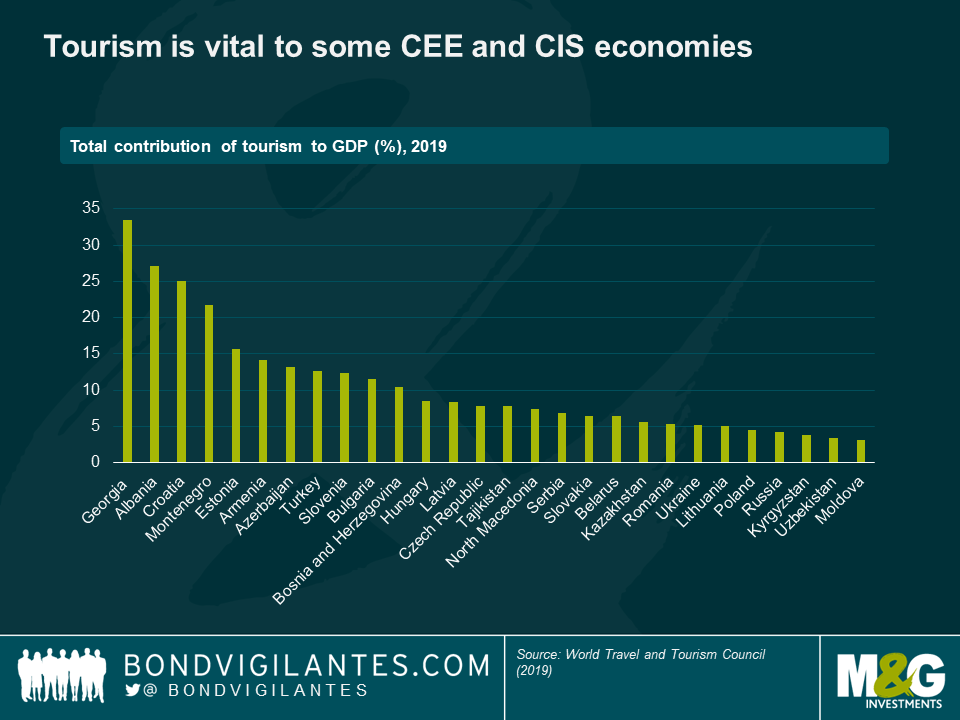

The tourism industry is important for many European countries, including developed ones – with Iceland, Cyprus and Greece topping the ranks in terms of the contribution of tourism to GDP. However, it is even more vital for some CEE (Central and Eastern Europe) and CIS (Commonwealth of Independent States)* economies.

*Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan.

Georgia is by far the most affected country in the region. According to World Travel and Tourism Council, the total (direct and indirect) contribution of tourism to its GDP more than doubled this decade, reaching 34% in 2019. In its May report, the IMF forecasts a two-third drop in foreign tourist revenues in Georgia this year. The corresponding negative impact on GDP growth may not be as catastrophic as these numbers seem to suggest (as some labour and capital unused in the tourism industry could be reallocated to other industries), but it will still be very notable. Some small economies on the Adriatic coast (Albania, Croatia, Montenegro) come next in terms of relative vulnerability in the region. In Albania’s case, the need to reconstruct infrastructure following the devastating earthquake in November will likely mean an even deeper drop in tourism this year. Importantly, tourism-dependent economies also tend to have a relatively low share of manufacturing exports in their GDP, which could limit their economic recovery even when growth in developed Europe starts picking up.

Can an EM country actually benefit from widespread travel restrictions and people’s unwillingness to travel far? Somewhat paradoxically, the answer may be yes for a couple of countries in the CEE and CIS region. For example, in Ukraine, outbound tourism expenditures (i.e. by Ukrainian residents abroad) tend to exceed significantly the receipts from foreign tourist arrivals. According to the World Tourism Organisation, this difference has been as much as 5% of GDP in recent years, despite Ukraine being one of the poorest countries in Europe. A similar situation to a lesser magnitude can be observed in some other countries as well, including Uzbekistan, Armenia, Romania and Russia. A note of caution though – the data on outbound tourism is collated using the information supplied by the destination countries and has its limitations. In particular, it might be somewhat distorted by migrant workers, which could be true for Uzbekistan, Armenia and partially Ukraine, as well as some others. The Russian case may also seem a bit surprising given the abundance of history and natural beauty, but it probably just demonstrates that infrastructure development and other factors such as the visa process tend to matter more for tourism inflows.

It is clear that, due to the significance of outbound tourism, some countries are unlikely to suffer much from travel restrictions and lower willingness to travel. And in some, this could even exert a positive influence, at least on the balance of payments and exchange rate dynamics. For example, the National Bank of Ukraine estimates that outbound tourism could drop by about half this year, contributing to a narrowing of the current account deficit compared to 2019 (excluding the one-off fine paid by Gazprom). A net positive impact on GDP growth may appear if such countries also manage to redirect those normally spending their holidays abroad to domestic destinations this year. In the majority of CIS countries, domestic tourism already matters more than foreign.

Elsewhere in CEE, Turkey and Romania have a significant share of domestic tourism, making local travel restrictions and attitudes among residents almost as important as those for foreigners. Many countries have already started to adopt measures that would support their domestic tourism industry. In Russia, the government has also recommended its citizens to spend their summer holidays within the country, with local travel restrictions likely to be lifted much earlier compared to those for foreign travel. In almost all other CEE countries, which are much more reliant on foreign tourism, such policies are likely to be a lot less effective. The reason is that they just do not have enough wealthy residents to substitute for the drop in high-spenders from developed European countries, who are likely to prefer local tourism this year.