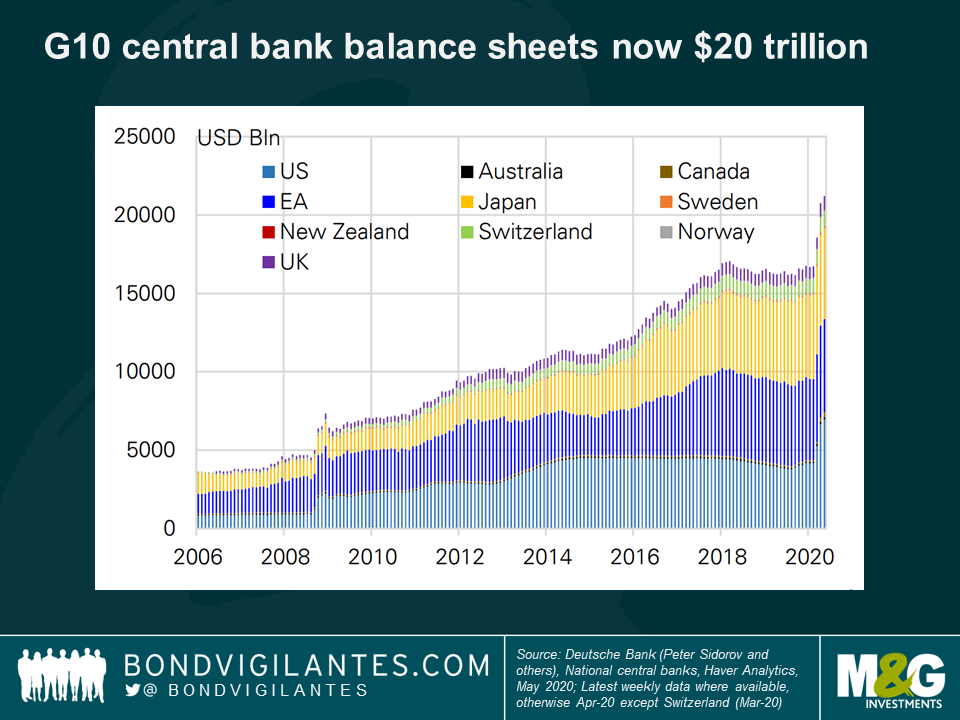

One common theme in market commentary of late has been the unprecedented use of the word unprecedented! One thing that used to be unprecedented and is now commonplace is central banks buying corporate bonds. Now this seems to have become conventional monetary policy, it is worth asking “why?” and “is this appropriate?”.

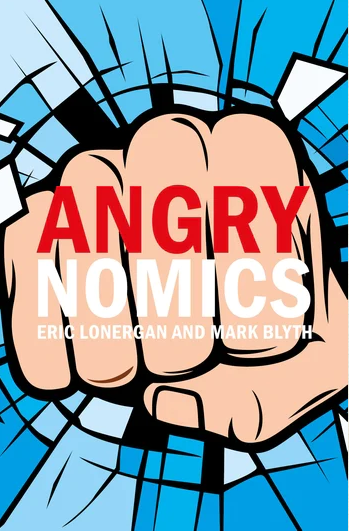

We first wrote about corporate bond purchases in 2009. Back then, it was a new and unprecedented tool. Now it is a regular weapon in the central bank armoury (see chart above), and even the Fed has joined in this time around. One of the consequences of the great financial crisis was a change in how the authorities ran the financial system. The main engine of economic liquidity at the time was the banking sector. It borrowed short and lent long, recycling capital; this is an important economic mechanism and was powered by monetary policy. This mismatch of term risk was mitigated by capital regulations, financial supervision and the back stop bid of central banks and governments, respectively as lenders and guarantors of last resort.

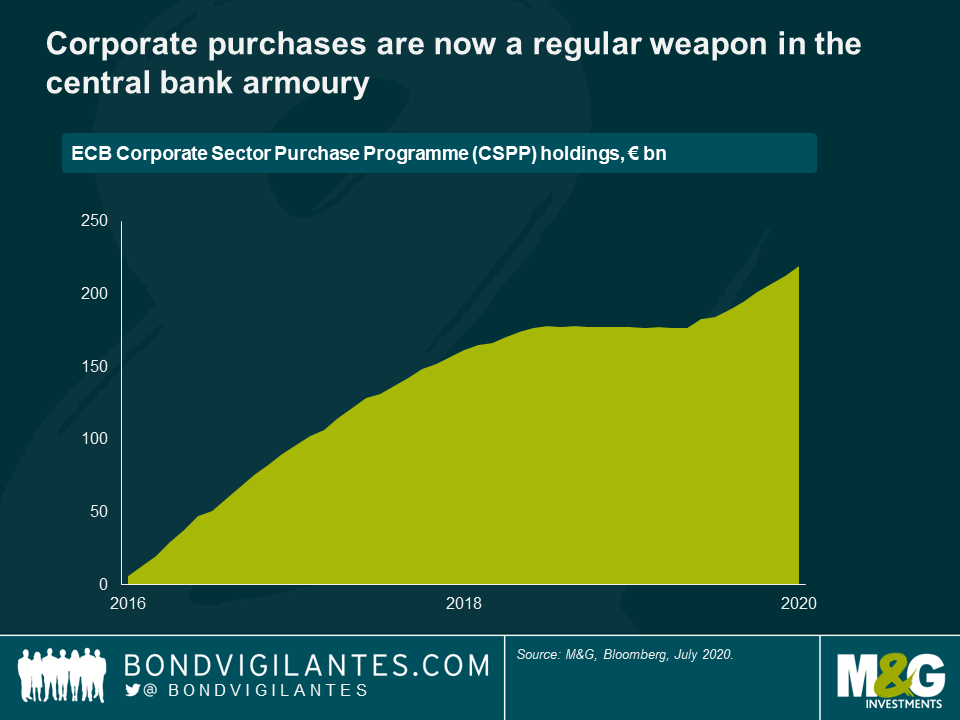

The financial crisis showed the vulnerability of this system which we and others have regularly commented on. A new system was required. Banks were discouraged from lending and have adjusted accordingly: their vulnerable function in the cycling and recycling of capital has been supplemented/replaced in part by the development of a term matched funding model. This is clear from the huge explosion of corporate bond debt outstanding, while credit extended to businesses and consumers has plateaued (see chart above). The effects of this transition, replacing short term bank debt with long term capital, are twofold:

- There is less liquidity around as it is harder for issuers to borrow money. The corporate bond market is a more laborious, and potentially expensive, route to financing than the established banking market. This results in growth being dampened as the capital markets are less dynamic in nature. A negative.

- The economic cycle becomes more stable as it is harder to create the booms and busts that come with a rampant banking market. A positive.

These two effects have been observable since the great financial crisis. Growth has been slow and steady, not high and volatile.

We are now facing a significant economic slowdown in response to public health needs. The governments and central banks of the world needed to respond rapidly in response to this historic event. In any crisis, it is the function of central banks to act as lender of last resort. The more stable financial market structure since the great financial crisis also needs to be part of the traditional crisis backdrop. Therefore, corporate bond quantitative buying programmes to stabilise markets by enabling the corporate bond market to function is appropriate, and a normal policy action.

The new buyer on the block is the Fed. It has been limited in the past in its intervention in the capital markets, but has now become comfortable in supporting the matched funding that the corporate bond market provides. Though new to corporate market purchasing, the Fed has a history of heavily intervening in the private credit markets with previous substantial MBS buying programmes. Its recent actions are an extension of the need to support term-matched funding markets, like is has done historically in the US housing market.

Though the post financial crisis system has evolved into a more stable one, it still needs supporting in times of crisis. Corporate bond buying is a natural function of central banks to support the capital markets functioning as an efficient recycler of capital.

The COVID-19-induced slowdown of the past few months has been different from past crises for a number of reasons. One of the most significant differences has been the greater ability of emerging market central banks to provide support to their economies, as we wrote about a few weeks ago. An interesting example is that of Indonesia. Last week, Indonesia’s central bank (Bank Indonesia – “BI”) cut its main interest rate (its seven day repo rate) by 25bps, from 4.25% to 4%. This was the second consecutive 25 bps rate cut in two months, the fourth this year, and brings Indonesia’s interest rates more in line with its Asian peers. Like many other central banks, BI has had to perform a delicate balancing act between supporting the economy during the pandemic and maintaining investor confidence and a stable currency. Indeed, given 40% of total corporate and government Indonesian debt is denominated in foreign currency, ensuring a stable rupiah is critical to the country’s economic prosperity.

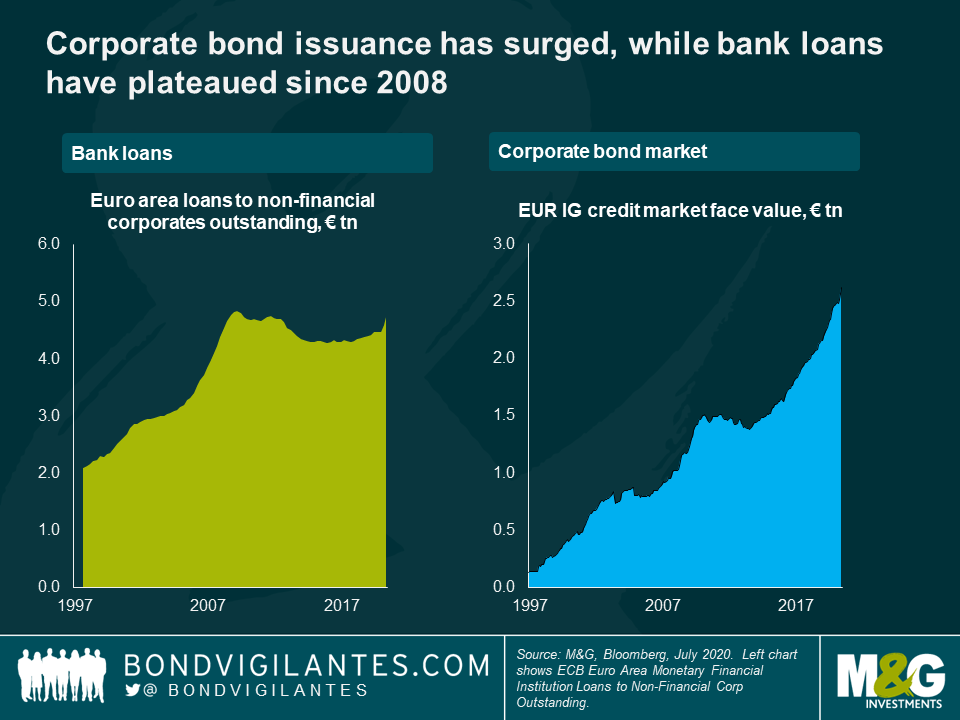

In order to contain the virus, the government started to impose large scale social distancing in March. Unfortunately, these measures have proven only marginally effective so far in preventing the spread of the virus, at least according to the official numbers (see chart below).

The recently imposed lockdown measures, combined with weaker global demand, have taken a significant toll on Indonesia’s economy. Real GDP growth is expected to be around zero for 2020, after averaging above 5% over the past decade. Imports are down around 14% versus last year, while unemployment and poverty rates are likely to increase substantially. As a result, the government announced a series of emergency stimulus packages aimed at directing more spending towards healthcare, social protection and businesses.

While the government has received some criticism for its ability to deploy assistance quickly in such a large and fragmented country, the initial pandemic response plan announced on 31st March was interesting for a couple of reasons. First of all, this initial plan allowed Indonesia’s budget deficit to increase beyond the statutory limit of 3%, until the year 2023. Indeed, as a precautionary measure, Indonesia’s budget deficit had been capped by law at 3% ever since the 1998 global financial crisis. For the year 2020, the government now expects the budget deficit to be 6.3% of GDP. Second, the regulation also stated that the government could finance the new pandemic spending plan through the issuance of additional bonds and, importantly, that these bonds could be purchased directly by the central bank.

This debt burden sharing scheme was finalized and revealed by the Indonesian authorities a few days ago. It provides for IDR 900 trillion of new debt-financed emergency pandemic spending (5.6% of GDP), of which the central bank will buy up to two-thirds via private placements and market auctions. This is expected to save the government around IDR 40 trillion in interest expense in 2020. More importantly, this will significantly reduce the supply of government bonds that needs to be absorbed by the private sector this year, helping to reduce yields and supporting the currency.

While BI has purchased Indonesian government bonds in the past, such an explicit and transparent reference to future debt monetization and collaboration between the government and the central bank is quite surprising for an emerging market. In addition, BI’s approach—aimed at reducing the interest burden for the government while maintaining higher interest rates and therefore the appeal of the debt for the private sector—is also relatively innovative.

On the flipside, BI’s actions raise the issue of central bank independence, moral hazard, and questions around how investors will react to a plan that directly subsidizes government spending and could encourage it to spend irresponsibly. To counter this argument, the Indonesian finance ministry points to the country’s track record of fiscal discipline and highlights the temporary aspect of the scheme, in that which is clearly an extraordinary state of events.

Economic textbooks also predict that such rapid increases in money supply should be inflationary. Research from Standard Chartered Global Research, looking at the historical relationship between changes in money supply and currency movements in Indonesia, concluded that the inflation rate could potentially increase by 2.4% all else being equal. That being said, one of the lessons of the past decade has been that the relationship between money supply and inflation can sometimes be quite tenuous, especially when private demand remains subdued. BI also has the option to tighten monetary policy (for example by selling back the special pandemic bonds or increasing bank reserve requirement ratios) at some point in the future, should inflationary pressures start to build up.

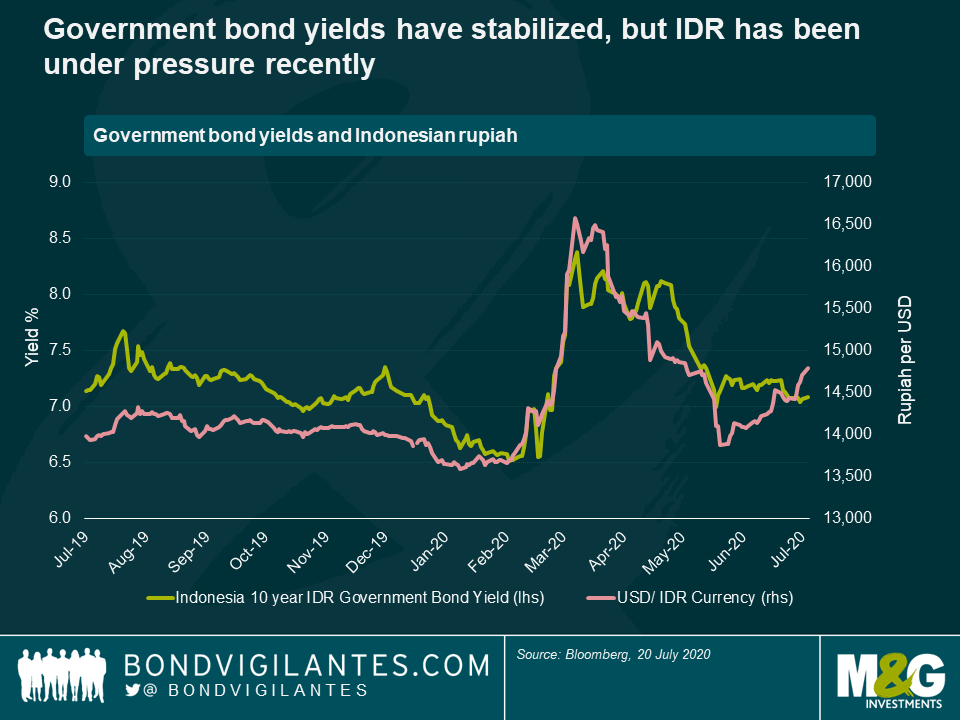

How have Indonesian local currency government bonds performed in this environment? After having sold off in March, government bond yields have stabilized. On the other hand, the currency has been under pressure once again over the past month, declining by 3.5% versus the US dollar. The cost of hedging Indonesia rupiah in the forward currency markets also remains relatively elevated, a sign of cautious investor sentiment.

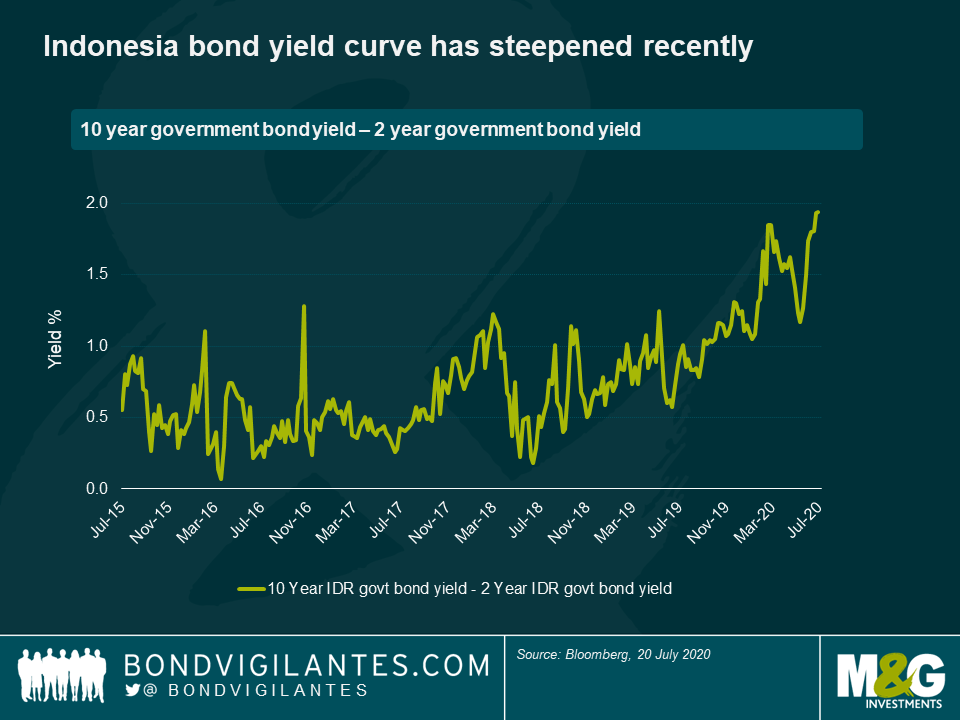

At a 7% yield, Indonesian government bonds are therefore attractive from a pure carry perspective, especially when compared with other investment grade local currency bonds in the JP Morgan GBI EM index (though non-resident investors should keep in mind that they will be subject to a 20% withholding tax, which will reduce their returns). In addition, while most of the rate cuts for this year are probably now behind us, the announcement of the debt burden sharing scheme earlier this year has led to a steepening of the yield curve. This leaves ample room for investors to benefit from a potential flattening of the yield curve should, for example, the budget deficit and government bond supply ultimately be lower than currently anticipated.

As for the currency, given the high degree of foreign ownership of Indonesian government bonds (around 38% for local currency bonds according to Moody’s), it has always been and is likely to remain quite volatile. For the currency to appreciate materially from this point onwards, one would probably need to see a sustained improvement in global investor sentiment and a return of investor flows into EM local currency assets in general, or to Indonesia in particular.

This in itself is conditional on the speed of the economic recovery and any material progress made in overcoming the virus. While visibility in this area remains low in the short term, the new debt burden sharing plan gives Indonesian authorities greater ability to provide support to Indonesian households and corporations that need it the most.

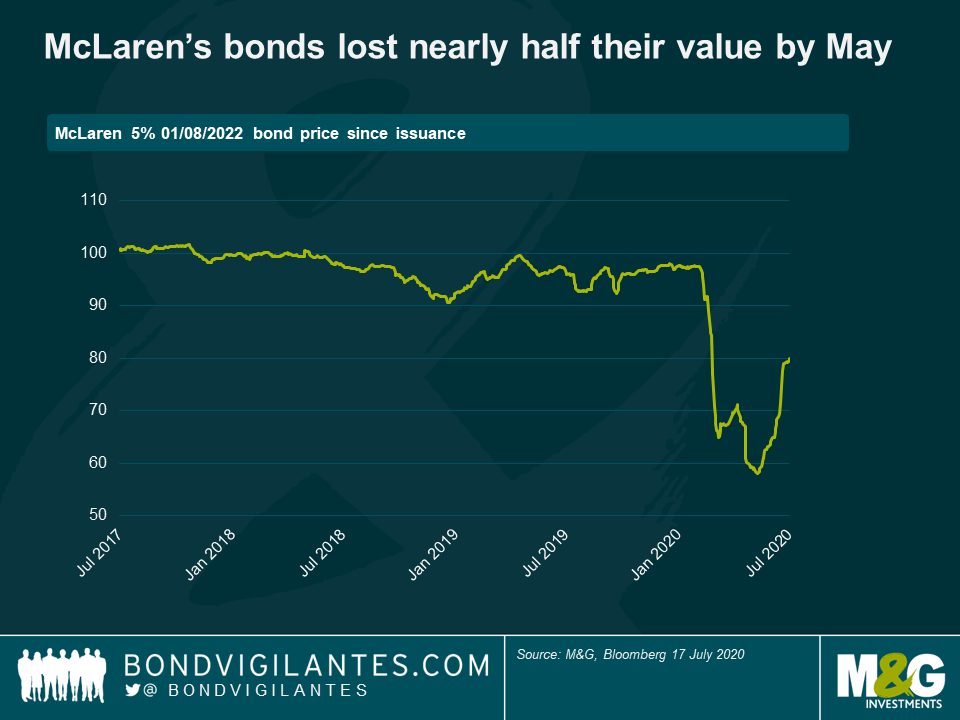

Covid-19 has taken lives, dramatically reshaped the way we live and work, and challenged our view of a safe and stable world. Those of us who work in investment management, especially high yield fund managers like myself, have seen the pandemic put many businesses under severe financial stress. British high-end sports car maker McLaren was one of them. The company’s activities have been badly disrupted and the company’s liquidity came under extreme pressure. It urgently needed to raise hundreds of millions of pounds of cash, despite having recently launched a strategic cost cutting and capex reduction plan.

What can a company do when it needs to raise this much cash? It can sell assets, borrow more, or raise more equity. McLaren has an all secured capital structure. This means that all of its debt is backed by a pool of the company’s assets or collateral, from the physical assets like its headquarter buildings in Surrey and its collection of heritage cars, to intangible assets such as its world-famous brand. McLaren’s secured bonds were trading in the mid-50s cash price in May and yielding more than 30%, implying serious concerns about the viability of the company and whether bondholders would get their money back. With the company unable to sell its secured assets and the owners unwilling to put more equity into the business, McLaren decided to explore loopholes in the bonds’ covenants in order to borrow more debt, and at a cheaper rate than its existing bonds. It proposed to transfer the headquarter properties and heritage car collection into a new “unrestricted subsidiary” outside the existing “restricted” borrower group. It would then raise fresh debt secured on the assets transferred to this subsidiary. This is known as a “J.Crew style transaction”, after the US retailer’s 2016 debt restructuring in which it put its brand and other intellectual property into a new entity outside the restricted group of existing debt, and used the entity to borrow more debt. Secured bond holders were now facing a dilemma: if they agreed, they would lose a valuable part of their collateral; if they didn’t, then the company would imminently run out of cash and they might lose all their money, unless they stepped in and funded the shortfall themselves.

But how could McLaren do this when the existing bonds were secured on those assets? McLaren took the bond trustee to the UK High Court, arguing that this was matter related to the “intercreditor agreement” that governs relationships between different borrowers. This falls under English Law, unlike the bond indenture which is under New York Law. Their hope was that the English court would be less capable of interpreting a New York Law indenture. Meanwhile, a group of more than 70% of the existing bondholders was quickly formed and they hired a law firm to push back against the newly proposed fundraising. With the company only submitting hypothetical transactions, the High Court required a specific new fundraising plan. Ultimately, McLaren backed down and called off the lawsuit, instead opting to raise a £150m shareholder loan from the National Bank of Bahrain (McLaren’s majority shareholder is Bahraini sovereign wealth fund, Mumtalakat). In exchange, bondholders agreed to amend and loosen some of the bond covenants to allow the sale of or a portion of the heritage car collection (provided at least £150m worth of vehicles was retained in the collection), and the sale of headquarters properties (provided that the first £85m of proceeds were used to repay the bond at par). The amended covenants also prohibit the transfer or sale of intellectual property.

The outcome of the McLaren case can be deemed a success for bondholders. We avoided a “J.Crew style” transaction, the business now has the much needed £150m extra cash cushion, and the bonds’ price has significantly recovered (see below). Despite the Covid crisis, June was a record month for high yield issuance and we’ve seen numerous deals with a trend to weaker covenants as investors prioritise yield over protection. In this environment, an ability to analyse, understand, and indeed enforce bond covenants is more important than ever.

The first half of this year saw one of the fastest and most aggressive market corrections in history, as Covid-19 spread around the globe. Just as unprecedented was the speed and extent of the subsequent recovery, thanks above all to governments and central banks having sent in the cavalry to boost liquidity and plug the consumer confidence gap. Combining fiscal and monetary stimulus, the global policy response is estimated to be $14 trillion and counting. With all this in mind, what’s next for global markets as we enter the second half of 2020 and beyond?

The 2020 Taper Tantrum

The second half will be all about the new Taper Tantrum. The first one was about the Fed’s balance sheet unwind, leading to a surge in Treasury yields as the central bank announced the tapering of its quantitative easing (QE) programme in 2013. This one will be about the end of furlough schemes in developed markets.

Countries are opening up again in order to limit economic damage, especially in the northern hemisphere where governments are keen to support growth through holiday spending. In the absence of a vaccine, this means that an acceleration of Covid-19 cases is almost inevitable, even with measures such as local lockdowns. However, death rates will be lower than they were in the “first wave” for a number of reasons: we now have better treatments (e.g. steroids cut death rates in intensive care units), we have learned lessons on shielding the most vulnerable, and very sadly, many of most vulnerable may have died already in the first wave. Most developed economies should return to some form of normality.

However, despite the recent rebound in employment (look at the US jobs numbers last week), unemployment is still exceptionally high. US unemployment is up 12 million from February, while in the UK we have over 9 million people out of work—more than a quarter of the UK workforce. So far, the economic damage done to individuals has been cushioned to a large extent by furlough schemes, in which the government pays a large percentage of salaries for staff whom would otherwise have been laid off. As a result, with little to spend money on during lockdown, many people have been able to save or reduce debts.

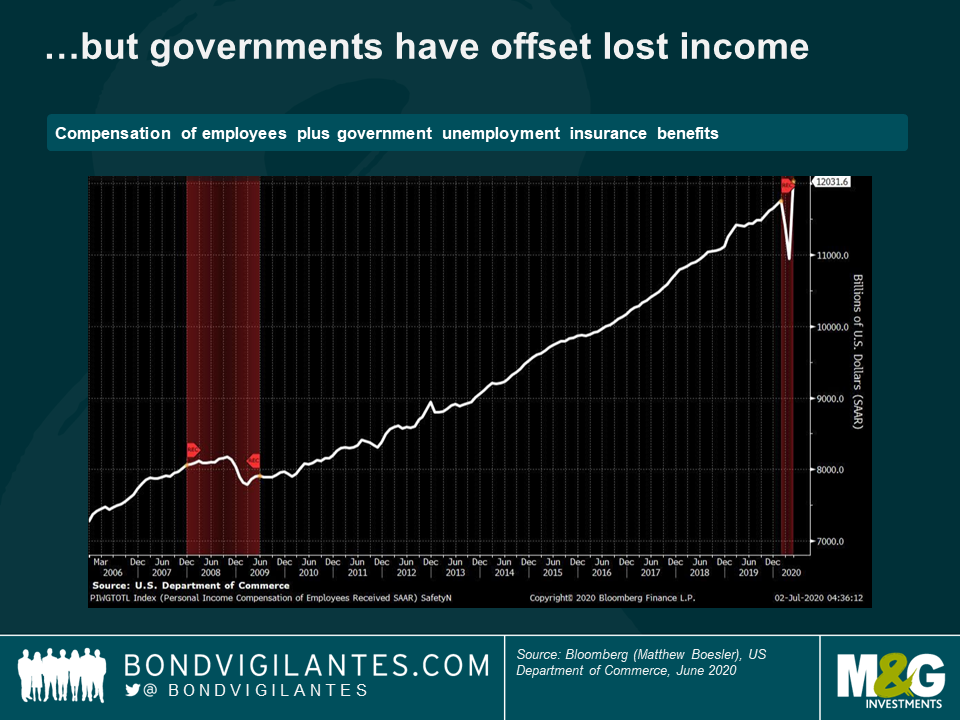

In the US, thanks to the CARES Act, the largest economic stimulus package in US history, we have a situation in which some workers have actually been better off being out of work than they were in their previous jobs. With direct payments to Americans and loans to business, the $2 trillion Bill amounts to 10% of US GDP, and is much larger than the $0.8 trillion Recovery Act of 2009. Adding together compensation of employees plus government unemployment benefits, we have the strange situation in which people in the US are receiving more income on average now than they were before Covid-19.

This is a rather odd recession: they don’t normally send personal incomes soaring.

The danger is in the taper

But what will happen when this stimulus begins to wind down? Government debt levels have exploded since March as tax receipts collapsed and unemployment costs rocketed. Deficits have moved well above 10% for most developed market economies, while debt-to-GDP ratios have generally moved to, or above, 100%. While there’s a lot of debate about whether this matters (see Stephanie Kelton’s recent book, The Deficit Myth, which suggests that we can print money to get ourselves out of the problem; or Eric Lonergan (of M&G) and Mark Blyth’s Angrynomics, which says that having negative sovereign interest rates makes this a time to invest in infrastructure), most governments want to start to taper assistance to the economy later this year. In the UK, this means that government furlough payments will be reduced in August and October, putting some of the wage burden back onto employers.

What happens then? In anticipation of furloughs ending, UK retailers in particular have already announced mass redundancies. How many of the world’s furloughed workers don’t realise that they are actually unemployed? For this reason, plus the continued impact of Covid-19 on global travel and trade along with social distancing nervousness (however reduced from its peak), talk of a V-shaped recovery seems difficult to square with the environment we now face, despite low rates and some continued fiscal stimulus.

Lessons from history

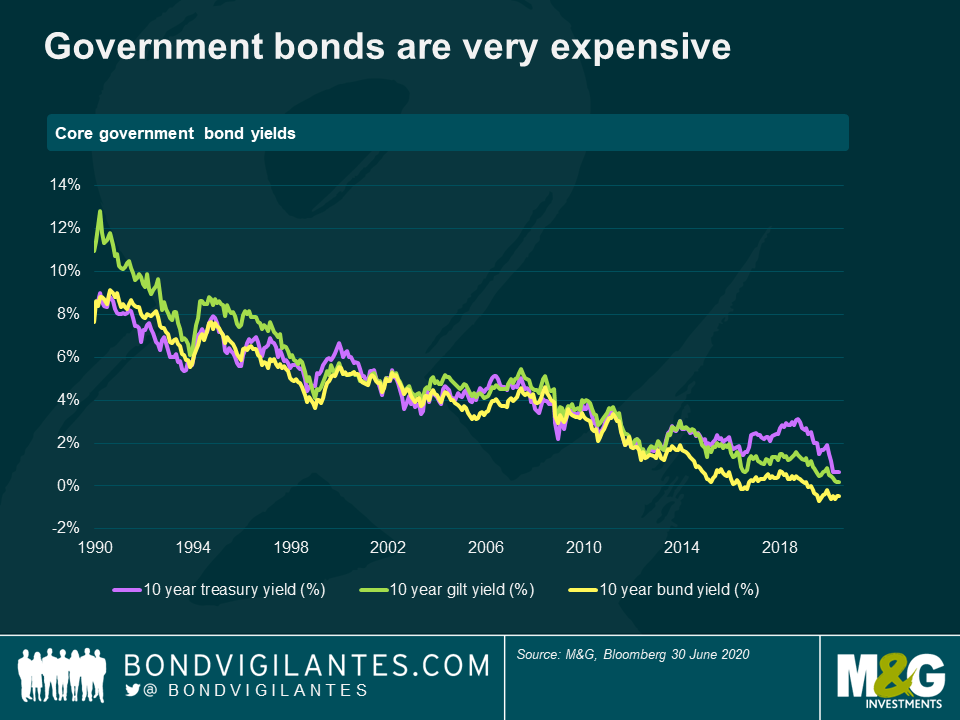

It is likely that there will still be more fiscal stimulus and debt levels will continue to rise from here. How will we deal with them? The usual three options are: grow, inflate or default. The answer is basically the same sort of policies that allowed the UK to deleverage from 250% debt-to-GDP after the second world war. These included forms of financial repression like forcing high bank ownership of government bonds. In the US, it involved pinning bond yields to low levels – like we have seen in Japan since 2016, and in Australia in March this year. Such yield curve control (YCC) is already under active debate within the Fed (YCC is different from QE in that it targets a bond price or yield, rather than simply being a purchase of a set volume of bonds). Might we also see negative interest rates from the BoE and Fed? On a further slowdown it is likely.

We should also consider central bank independence. Former Bank of England Deputy Governor Paul Tucker has warned that, as the Bank is now buying basically the same value of gilts as is being issued by HM Treasury (as well as offering the government a Ways and Means overdraft for lost tax revenue), it is at risk of being seen as the financing arm of the UK authorities.

The return of inflation?

Does this make inflation more likely? The jury is out, and this largely depends on who wins the battle between labour and capital in the recovery. Labour has lost out for decades now. Will Covid-19 change that? The data so far are not promising: the latest research from the US Brooking Institute think tank says that it is the bottom 20% of wage earners that have suffered the highest unemployment rates, so hopes that we would emerge from the crisis wanting to reward low-paid key workers (nurses, delivery drivers, supermarket staff) might be dashed. There’s still a chance of some supply side inflation, thanks to food going unpicked and disrupted logistics. Shopping basket inflation did rise in March, as shops ended promotions and limited product ranges (and this inflation was inflicted disproportionately on lower income households as a result of how lockdowns have pushed them to buy more food while not spending as much on other, less inflationary items and activities). But demand-driven inflation seems very unlikely overall.

Received wisdom is that QE = inflation. Is this true? The money supply expansion is huge – but so is the collapse of the velocity of money (i.e. the speed at which it circulates in the economy). Some argue that the most powerful effect of QE is that on a currency: as money is printed, the currency depreciates and inflation is generated through higher imported goods prices. But what if everyone is doing QE? What if everyone is trying to get their currency down? It has no impact. Famous bear Albert Edwards goes further, to say that YCC will be even less inflationary, since countries like Japan have been able to keep yields low without even having to buy many bonds – the signalling effect is so powerful that there’s not even a monetary expansion.

Positioning for the new taper tantrum

Credit

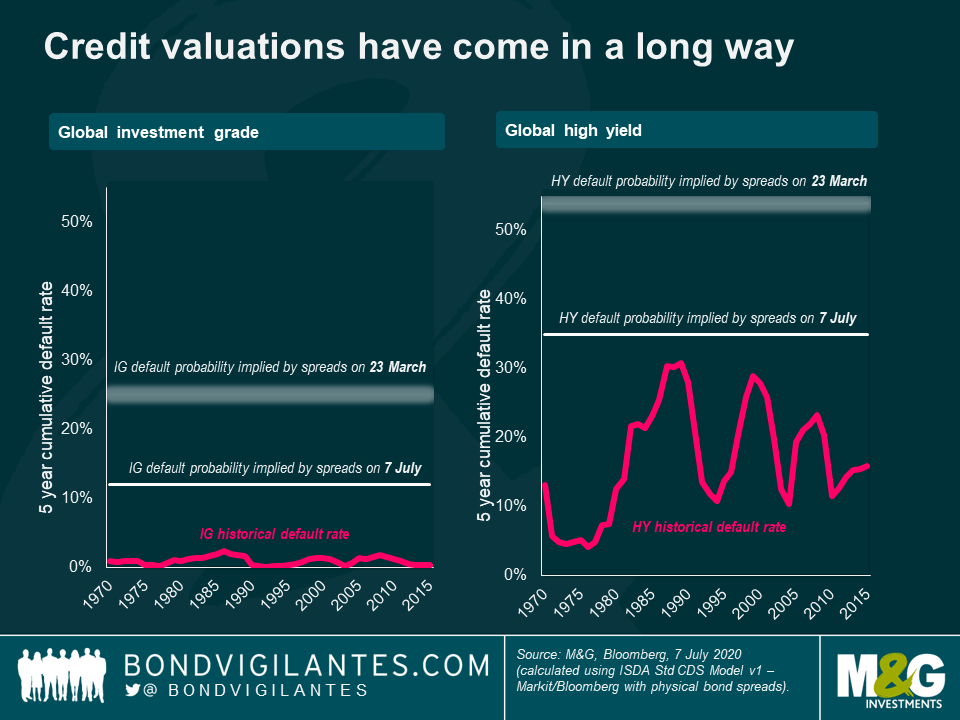

We’ve come a long way since the lows of March, which offered some great opportunities to be overcompensated for default risk as a credit investor. Corporate bonds, which at their lows were pricing in IG and HY default rates of 25% and 54% (23 March 2020) respectively, are now closer to fair value (pricing in 12% and 35% at 7 July 2020). Undoubtedly this has been driven mainly by central bank buying, particularly in high yield where we have seen and can expect to see more defaults.

Despite considerable volumes of issuance, high yield spreads have come a long way. The main reason is not fundamental but rather the action of the Fed, which has for the first time been buying high yield ETFs and high yield bonds which were downgraded after 22nd March. It’s hard to get excited about credit valuations at these levels. There is still some value in investment grade: these companies are the big employers, so it is politically easy (and arguably a decent policy tool) to support them.

The Fed’s support also begs the question, is it right that these companies survive? We have lost the creative power of destruction, where the old makes way for the new. Is capital really being allocated correctly and efficiently? We have seen how growth and productivity stagnates under these conditions in Asia at the end of the last century.

Developed markets

Despite the huge fiscal stimulus we have seen, it is difficult to be too bearish on government bonds now given the yield controlled world we live in. And bonds like bad news: while they are clearly very expensive, they do offer potential upside in the event that negative sentiment returns to markets in the second half. With inflation unlikely to rise significantly in the short term, I don’t mind owning duration.

In Europe, the planned recovery fund and continued Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) have been supportive. Just as important as the planned spend itself is the sentiment of burden-sharing, when it comes to helping contain EU break-up risk. Despite some resistance to the stimulus plans from the more frugal Euro nations, Italian BTPs and other peripheral bonds have strongly outperformed core government bonds since the announcement. I’m not convinced we’ll see much more outperformance from BTPs since their aggressive rally. Flows are slowing as spreads are compressing, so demand is likely to shift to other high yielding sovereigns in the region that have been less aggressively bought so far by the ECB and investors. For this reason I like bonds like 10 year Netherlands.

Emerging markets

One area in which I do see value is emerging market (EM) debt. Firstly, it offers higher real yields than developed market bonds. Also, EM currencies have lagged the recovery, meaning that some local currency bonds do offer attractive value (you can buy more per dollar). Emerging markets clearly face challenges due to Covid-19, particularly as a result of headwinds to global trade, but greater EM central bank intervention than we have seen before is helping and there are regional pockets of relative value. For example, I would expect Asia to outperform other EM regions, since high real rates make currencies here broadly attractive to investors. Additionally, many of these economies are net exporters and so this should also improve current account balances.

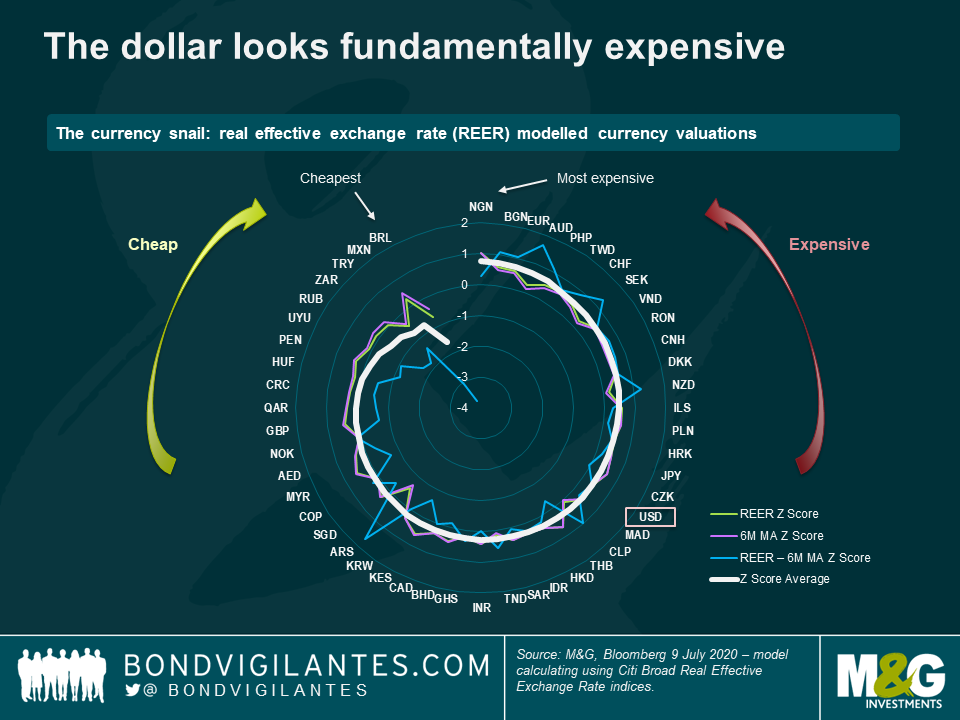

Currencies

We should see some mean reversion in valuations that moved aggressively in the first half. While EM local currencies looked fundamentally cheap across the board in the first half, going forward I expect to see some more moves based on fundamentals. I therefore anticipate rotating out of some of those currencies that have rallied aggressively (for example the Indonesian rupiah) to those where fiscal and central bank positions are strong, but valuations still look attractive (for example the Russian ruble). I would also favour higher-beta currencies (for example those that are heavily commodity-driven, or with a reliance on external rather than domestic demand) to capture any second half mean reversion. Likewise I am following central bank moves closely: currencies in those countries where central banks have been relatively conservative in expanding their balance sheets (e.g. the New Zealand dollar over the Australian dollar) are where I want to be (though in rates I would favour issuers where central banks are providing strong support).

Unlike many EM local currencies, the dollar looks quite expensive on a fundamental basis. Despite this, I do own some dollar exposure, as it does its job in a risk off environment. On balance though, I prefer the Japanese yen for the better diversification and risk off hedge it offers. With the ECB having removed a lot of downside risk in the region through their aggressive buying programme, I also like holding the Euro. It has become a very cyclical asset (rallying as sentiment improves, the opposite to the way the dollar is behaving), so I hold it against the safe haven currency of the region, the Swiss Franc.

Short term action, long term impact

The focus of financial markets moves quickly. We saw over the first half of 2020 just how quickly. After the deep and rapid panic-driven sell off as Covid-19 spread around the globe, the extent to which asset prices have recovered reveals markets’ new focus: the unprecedented magnitude of fiscal and monetary stimulus. With millions of jobs lost in a few months, there is no doubt to my mind that it is this stimulus which is now driving markets: they are being driven by technical factors, not fundamentals. I think the focus may change just as rapidly in the second half, and it will be to the other side of the coin: what will markets make of the inevitable end of the monetary and fiscal bridge?

Governments and central banks have, on the surface, succeeded in containing much of the financial fallout of the lockdown-driven fall in demand. The danger now is in the taper. In this light, it seems difficult to support the idea of a V-shaped recovery. And the short term response of governments and central banks brings up longer term questions. How will we get out of all this debt? Grow? It seems implausible that trend growth will be higher in the aftermath of this crisis than before. Inflate? Central banks haven’t been able to achieve their inflation targets even in the good times, so what chance do they have of inflating away the debt now? Default? There’s no need to default if you can print your own currency – but we might see some debt jubilees (cancellation of student loans for example), wealth taxes and confiscations, and even the cancellation of government bonds held by the central banks as part of QE. And what happens if the market stops believing that central banks are independent? Could that finally be the catalyst for inflation expectations to return to developed markets and, after decades of losing, will labour win over the power of capital this time round? The actions of a few months bring up these questions and more. We may have to wait for some years to learn the answers.

The inclusion of the Bulgarian lev and the Croatian kuna in the Exchange Rate Mechanism II (ERM II), which was announced last Friday, marks a crucial step for both countries to becoming the 20th and 21st members of the euro area. Bulgaria and Croatia won’t imminently join the currency union, though. As stipulated in the Maastricht Treaty, prospective members are expected first to demonstrate at least two years of exchange rate stability—in particular no devaluation of their currencies against the euro—in the ERM II. Further convergence criteria have to be met with regards to inflation, long-term interest rates and sustainability of public finances.

Undoubtedly, a membership in the euro area would have profound consequences for Bulgaria and Croatia. But, conversely, there would also be implications for the currency union as a whole when expanding into the Balkans. I survey three of them below.

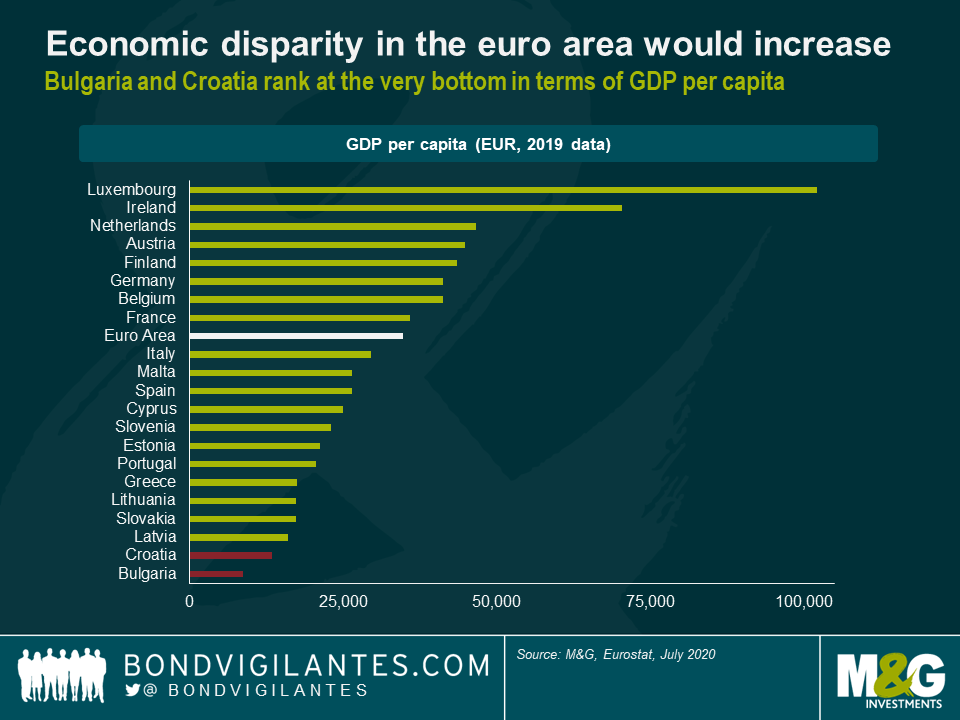

(1) Rising economic disparity

First of all, economic disparity within the euro area would rise significantly. Using 2019 Eurostat data, Croatia and especially Bulgaria have substantially lower GDP per capita numbers than any of the 19 eurozone members. The GDP per capita of Latvia—currently the worst performing euro area country by this measure—is still nearly twice as high as Bulgaria’s figure. Moreover, Bulgaria’s GDP per capita is only around one quarter of the euro area average and less than 10% of Luxembourg’s number. That’s a substantial discrepancy. In comparison, GDP per capita differences among the 50 U.S. states are much more benign. The figures of Massachusetts at top of the list and Mississippi at the bottom are only off by a factor of two.

Rising disparity would by no means be limited to GDP per capita. Also with regards to annual net earnings, disposable income, labour cost levels, etc., the lower bound of the euro area range would be shifted downwards when including Bulgaria. It should be noted, however, that there are other key economic parameters, such as unemployment rate or GDP growth, in which Bulgaria and Croatia have performed better than the eurozone average. Still, I think it is fair to say that the expansion into the Balkans would be accompanied by growing heterogeneity and inequality within the eurozone, which begs the question of what this may mean for cohesion and stability of the currency union.

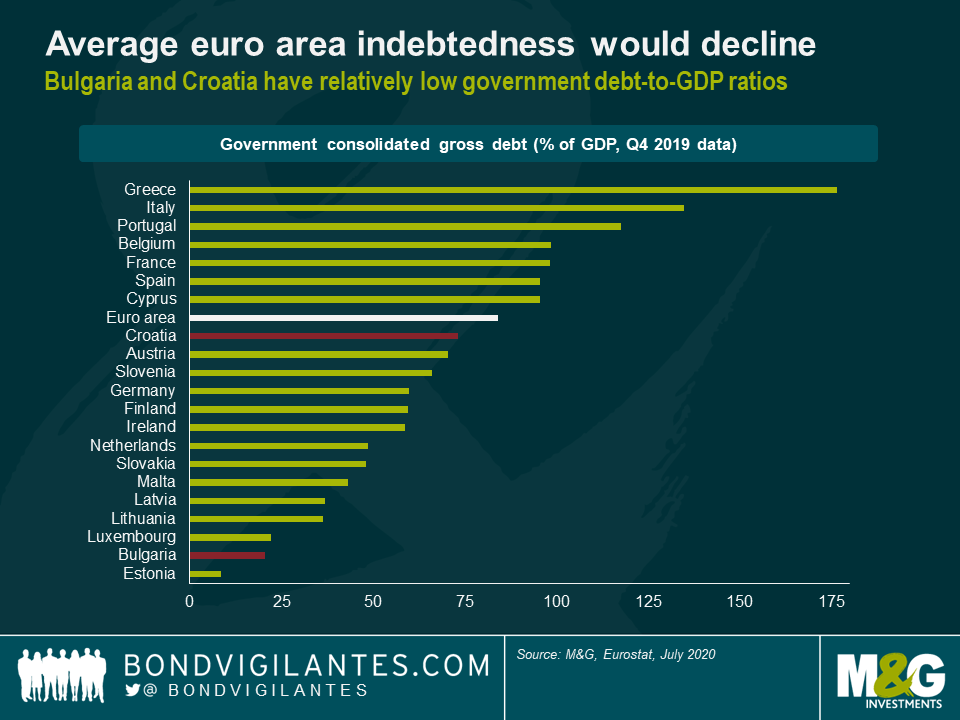

(2) Lower average government indebtedness

Second, average government indebtedness in the euro area would decline, if only marginally. Based on Q4 2019 Eurostat data, the government debt-to-GDP ratios of both Croatia (73.2%) and, even more so, Bulgaria (20.4%) are below the euro area average. In fact, Estonia (8.4%) is the only eurozone member with an even lower ratio than Bulgaria.

And, at least before the COVID-19 crisis struck, there was little reason to assume that government indebtedness was on the rise in Bulgaria and Croatia. In 2019, both countries had a budget surplus—+2.1% for Bulgaria and +0.4% for Croatia—whereas the euro area as a whole featured a budget deficit of -0.6%.

It should be noted that Croatia’s debt-to-GDP ratio exceeds the 60% maximum level, enshrined in the Maastricht Treaty, by more than 10 percentage points. But the rule hasn’t been enforced zealously in the past, to say the least, as both Italy and Greece joined the euro area with government debt-to-GDP ratios beyond 100%. Moreover, it is anybody’s guess whether or not the 60% limit will carry significance at all in a post-COVID-19 world in which public debt levels will have risen drastically across the board.

(3) Dilution of voting power of smaller economies in the Governing Council

Third, the expansion of the euro area into the Balkans would shift the power balance in the Governing Council of the European Central Bank (ECB) more towards the larger economies. The Governing Council is the ECB’s main decision-making body and is responsible for setting the monetary policy in the euro area. It comprises six Executive Board members and the governors of the national central banks (NCBs) of the eurozone’s member countries.

Up until 2014, all council members had both a voice and a vote at every Governing Council meeting. However, over the years the number of eurozone countries, and thus Governing Council members, grew, making consensus-building and decision-making increasingly challenging. Therefore, when Lithuania joined the euro area on 1st January 2015, a rotation system, not dissimilar to the one used by the Federal Open Market Committee of the Federal Reserve, was introduced.

In the new system, the total number of voting members in every Governing Council meeting is set at 21. The six Executive Board members have a permanent voting right at every meeting. The remaining 15 votes are allocated between the 19 NCB governors, who are split into two groups. The NCB governors of the five largest eurozone economies—Germany, France, Italy, Spain and the Netherlands—form the first group and share four votes. Voting rights rotate monthly, which means that every month one of these NCB governors will not be eligible to vote. The second group comprises the NCB governors of the 14 smaller eurozone economies, who share the remaining 11 votes. Hence, on a rotating basis, three of these NCB governors have to forgo voting at each Governing Council meeting. It should be highlighted, however, that Governing Council members without a current voting right are still allowed to attend meetings, present their arguments, participate in the discussions, and thus influence the decisions of the voting Governing Council members.

As it stands, the current voting system—21 votes in total, with tiering of NCB governors into two groups—will persist as and when Bulgaria and Croatia join the euro area. As both countries would be classified as smaller eurozone economies, the 11 votes reserved for this group of NCB governors would then have to spilt by 16, and five of these NCB governors wouldn’t be able to vote. The voting power of smaller economies in the Governing Council of the ECB would thus be diluted and the balance of power would shift more towards the larger economies.

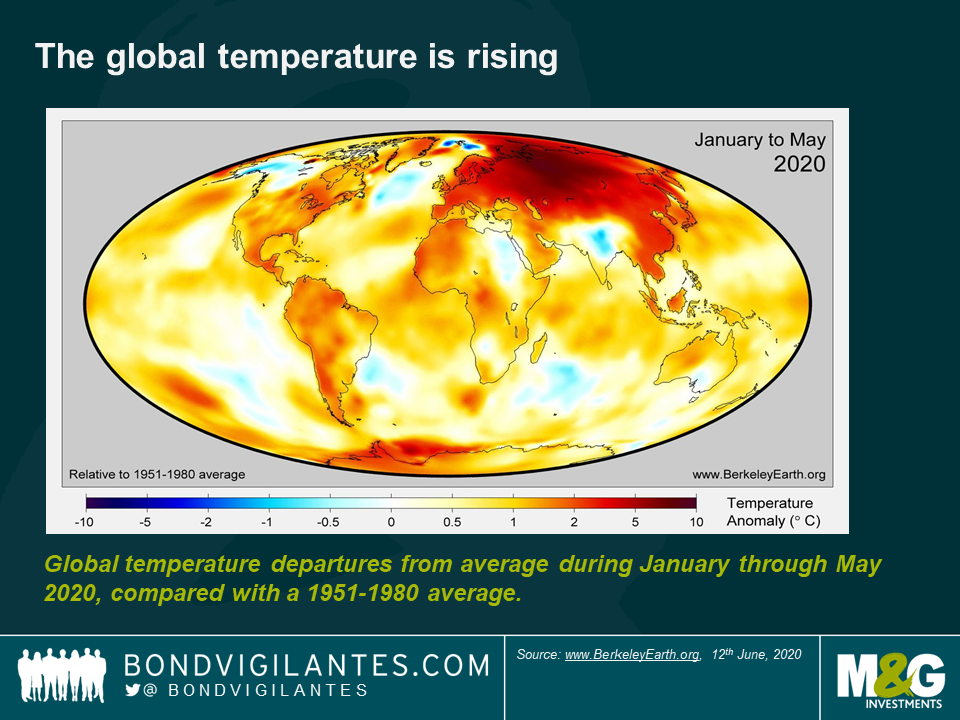

The EU has embarked on a mission to make Europe the first climate neutral continent by 2050. Rather unnoticed amongst COVID-19 headlines, the EU parliament approved the unified EU Green Classification System, also known as the EU Taxonomy for Sustainable Activities, on the 18th of June and turned it into law. A core pillar of the new regulation is to outline whether an economic activity qualifies as a green investment or not, so providing a clear industry threshold for green financing transactions. While the technical working group is still defining the screening criteria for certain segments of the market, it is clear that the eligibility criteria set are stringent. Undoubtedly, this is the right thing to do if we want to achieve the challenging goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels.

Global energy demand is set to continue to grow over the next 30 years, driven by a rising population and economic expansion. And while renewable solutions continue to see their market share increase, fossil fuels are still expected to make up at least 50% of the global energy mix in 2050 even under the most optimistic scenario, according to research from Barclays. The implication of this is that achieving a low-carbon world requires existing businesses, in particular brown industries, to decarbonize and mitigate climate risk.

The hurdle for carbon-intense businesses to issue green bonds remains high however. Such issuers fear coming to the market with a green bond and being criticized for it. It comes as no surprise that oil and gas names reflect a weight of only 0.47% in the BofA Merrill Lynch Green bond index, while their index weight in the BofA Merrill Lynch Global Corporate index is more than 8%. Despite this, I would argue that companies operating in brown industries are playing an important part in the energy transition we need. Many of them are sizable players, with large capital structures and research and development functions in place to accelerate the much-needed change. Just last month, Total bought a 51% stake in Seagreen 1, an estimated £3 billion offshore wind farm project in the North Sea. Not many players have the financial firepower and the ability to take on the construction risk for such a major project.

But what about activities that cannot be classified as green, yet play an important role in reducing a company’s greenhouse gas footprint? How can the investment industry encourage such behaviour for companies where the core of their business is not (yet) compatible with green financing?

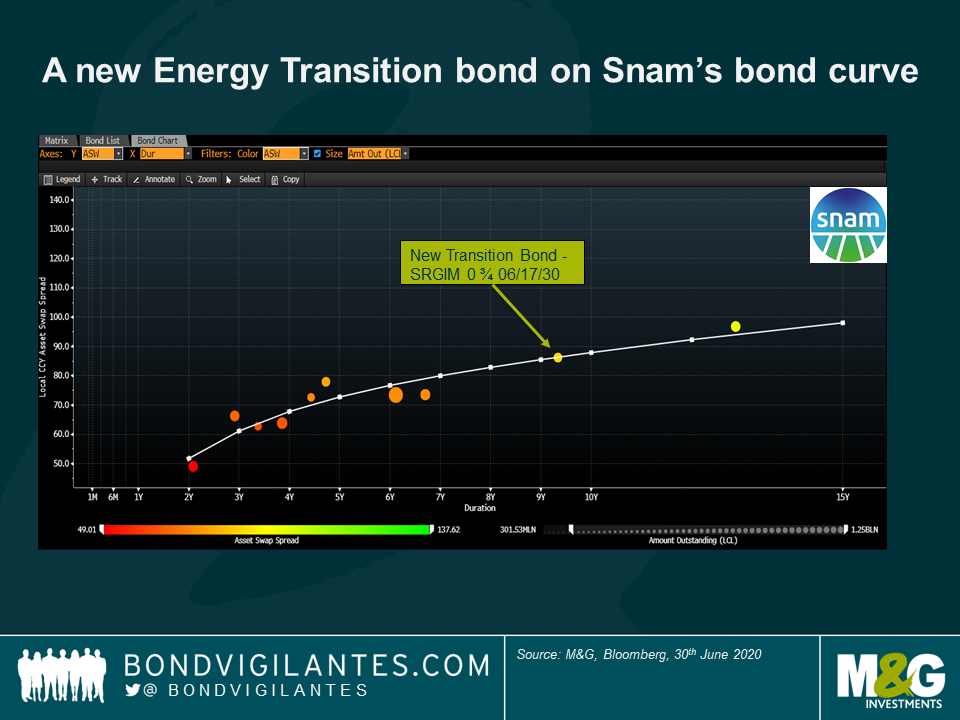

One possible solution to allow carbon-intense industries to receive funding from the sustainable investor base is Energy Transition bonds. These are bonds issued with the purpose of enabling a shift towards a greener business model. So far, this idea remains in its infancy, with only half a dozen such bonds launched. Last month, Italian gas transportation business Snam launched its first official Transition bond via a €500 million deal. The proceeds will be used to finance eligible projects related to energy transition as defined by the company’s Transition Bond Framework. For example, these proceeds can be tied to renewable energy projects by making gas pipes hydrogen ready, or to energy efficiency programmes by installing heaters with more efficient technologies to reduce methane emissions. The new deal was welcomed by bond investors, and was three times oversubscribed upon issuance.

Having said that, fixed income investors have already had their eyebrows raised in the early days of the Transition bonds market. In 2019, a beef producer issued a Transition bond with the aim of using those funds to buy cattle from suppliers that had agreed not to destroy more rainforest. Many would argue that the company shouldn’t be buying cattle coming from deforested areas in the first place.

This highlights the importance of having checks and balances in place, and is a call for industry-wide Transition bond standards. Market participants need a framework which outlines the eligibility criteria for the use of proceeds of such Transition bonds, including the minimum energy improvements that need to be achieved, how this is measured and reported, and the extent to which such a transaction must be linked to the issuer’s wider transition strategy. Only this will gain investors’ confidence and trust, and allow Transition bonds to become a more accepted and deeper market place. The EU taxonomy will provide some valuable signposts here to help measure whether a company’s planned use of funds is good enough to qualify as a Transition bond. If done rightly, Transition bonds can offer an important additional asset class for issuers alongside Green bonds, and with that help to prevent greenwashing in the green bond market.

With the right framework in place, energy Transition bonds could be the next evolution in allocating capital towards a low-carbon economy, close an important gap and help mobilize more assets to tackle climate change. Issuers can get better access to an increasing sustainable investor base, while bond investors would see their opportunity set increase substantially, all leading to a greater impact in mitigating climate risk. A win for bond investors, issuers and the planet alike.

Historically, one of the defining characteristics of emerging market (EM) economies has been that they generally have not been able to use monetary policy to stimulate their economies during crises in the way developed markets (DM) have. Usually, they have had to hike rates to limit capital outflows and defend their currencies, in doing so making economic recovery more difficult.

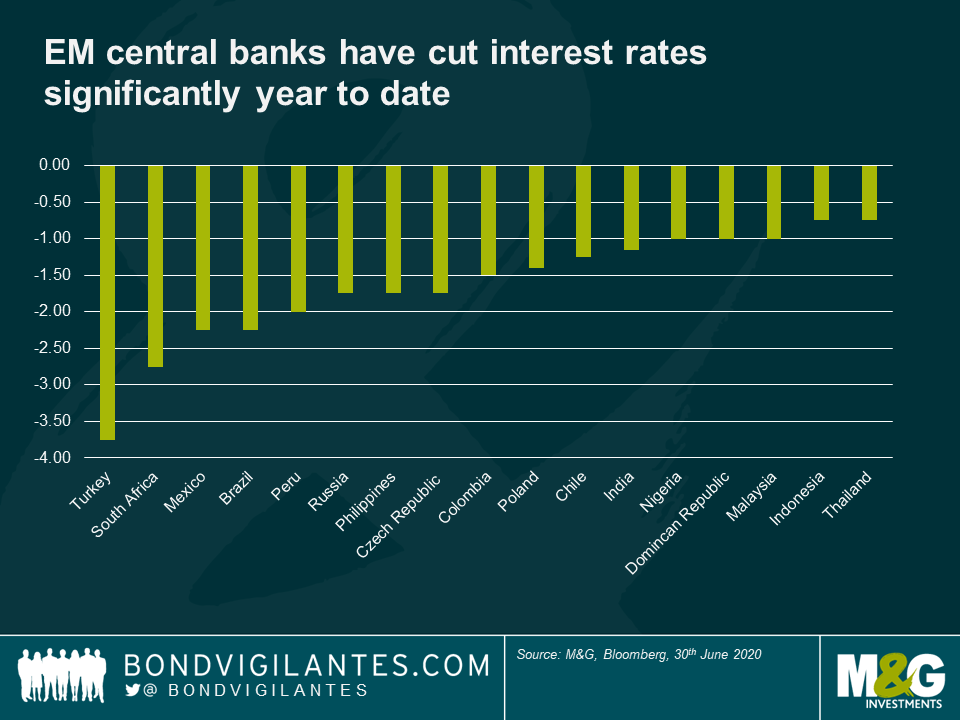

This is why it has been particularly interesting to observe the actions of emerging markets during the Covid-19 crisis that has just swept the world. We witnessed most EM central banks easing policy by cutting rates, some quite aggressively (see chart below), and I believe there could still be room for more. This is a very welcome development, and will be helpful in supporting economic activity during these difficult times. This is particularly true as local financing has gradually become more important across many EM countries that used to issue debt predominantly in foreign currencies, Brazil being a good example. While many EM currencies fell sharply during the first stage of the crisis, most have rallied significantly since then despite these cuts. One of the main reasons this has been possible is the low inflation we have seen in the recent past across most EM countries, and given expectations that inflation should remain low in the near future as demand has collapsed with the pandemic. The fact that the Fed has dropped rates to near zero has also been particularly helpful.

While this has resulted in interest rates in EM dropping to historical lows, potentially providing less support for EM currencies, the differential between EM rates and DM rates remains elevated, with most EM real rates still in positive territory (unlike those in developed markets). In my view, emerging markets therefore remain one area of the market in which investors looking for yield should be able to find it.

Perhaps even more surprisingly, several EM central banks have engaged in purchases of sovereign bonds, aka quantitative easing (QE), until now a tool used only by major developed market central banks (see below table for more details). As can be expected, the size of these purchases remains significantly lower than in developed markets, and in most cases is below 2% of GDP. Central bank balance sheets in EM remain smaller that in DM, and those with large balance sheets are typically those with large FX reserves rather than government assets. Another important difference is that central banks in EM typically have not reached the zero bound when setting interest rates, and most are unlikely to be able to do so. This raises the question of the relative effectiveness of QE given that conventional monitory policy is not yet exhausted.

To date, most EM central banks have been carrying out QE by buying sovereign bonds on the secondary market, as opposed to the primary market. While it can be argued that the end result is very similar, purchasing through the secondary market can help allay concerns that EM central banks are directly financing governments deficits, and can instead be seen as operations aiming to provide liquidity and support to the market in a period of stress.

The majority of those countries that have engaged in QE benefit from a relatively high credit quality (most of them have investment grade ratings) and have developed their local markets, gaining credibility in their ability to set fiscal and monetary policy. The actions of some countries, like South Africa and Turkey for instance, which are also engaging in asset purchases but were already suffering from some lack of credibility and questions about central bank independence, may raise more questions with investors in the longer run.

Taking into account the unprecedented nature of the current crisis, this stimulus has been very helpful in supporting local markets, and QE could be an important tool in the short term to help finance increasing budget deficits resulting from the crisis. However, at the end of the day, QE can be seen as a form of printing money. This could become problematic in the longer run if investors believe countries are using it as an alternative to fiscal discipline, and could lead to significant outflows from local markets if the market loses confidence, in turn fuelling potential currency depreciation and imported inflation. The fact that asset purchases have slowed since March in most countries as the market stabilised and asset prices recovered is a positive sign, as is the fact that EM countries have been able to issue significant amounts of local debt in the last two months. However, how easy it will be to reverse course remains an open question, and the track record of developed markets in winding down QE does not set a particularly encouraging precedent.

This new book by Eric (an M&G multi-asset fund manager) and Mark (an economics professor at Brown University in the US) is getting a lot of attention at the moment: Martin Wolf put it on his list of “must read” books for FT readers over the summer, and the book’s ideas are very much answering the big questions of today. Why are we all so angry? Where did these culture wars come from? Why have populist governments replaced the stable, sensible technocrats that we thought were a permanent feature a few short years ago?

By the magic of Zoom (not just for quizzes) I was able to speak to both Eric and Mark about the book. Here’s what they had to say about both the types of anger that have driven the crazy political world that we now live in, and their suggested solutions to the causes of that anger (clue: negative interest real rates are pretty useful here…).