The EU’s €750 billion recovery fund can be considered a major political achievement for the bloc. It’s good news for investors too, as the announcement helps to contain EU break-up risk as a result of Covid-19.

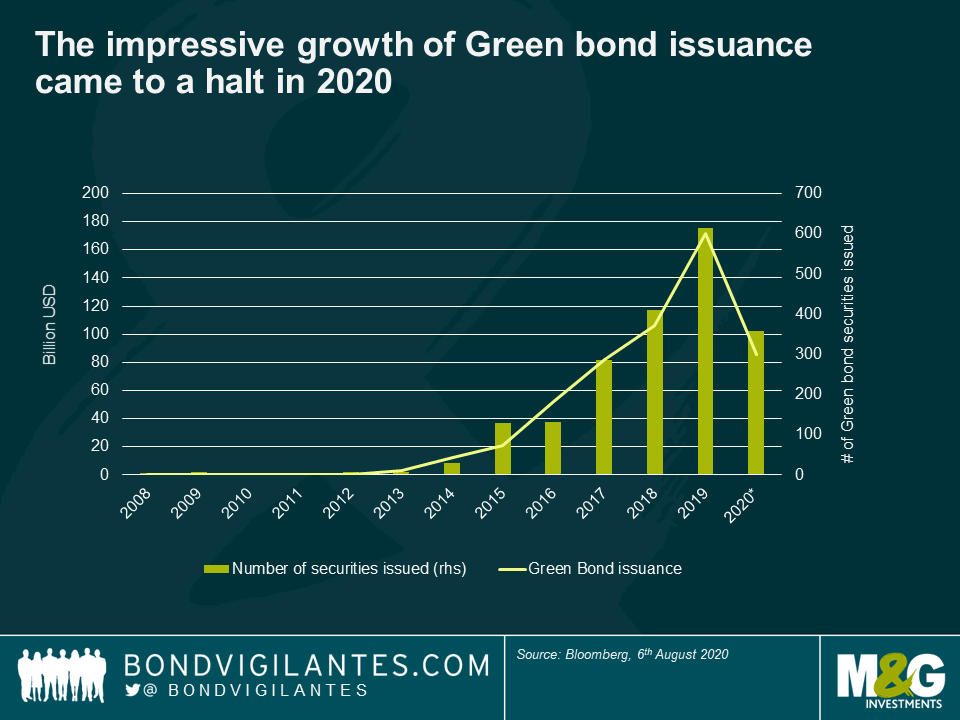

The plan has also received a positive reaction from green investors: the recovery fund can direct resources not only to hard-hit sectors, but also to sectors not directly affected by the virus, such as green technology and infrastructure. It is not yet clear how much of the EU’s future issuance will be dedicated to green bonds, but I would not be surprised to see the EU use its flexibility to help drive its target to become the first carbon neutral continent by 2050. This would certainly give a much needed boost to the green bond market, whose year-on-year growth story came to a halt in 2020.

Green bonds could serve as an attractive risk-free asset with a pickup

I would expect to see a good level of market interest for EU green bonds (subject to pricing), with demand coming predominantly from passive investors and investors with strict mandates for high quality assets. EU green bonds are anticipated to have a AAA credit rating and could therefore offer an interesting alternative to existing risk-free assets, such as German bunds. However, while the EU will become a sizable issuer of debt over the coming years, the total amount of EU bonds outstanding will still represent just a small fraction of outstanding German bunds.

I would therefore expect EU green bonds to trade with a small liquidity premium over bunds. There is also an element of redenomination risk embedded in bonds issued by the EU, which should also be reflected in some spread premium. EU green bonds might therefore appeal not only to sustainable bond investors, but also to portfolio managers looking for risk-free assets with a small yield premium. Furthermore, with the possibility of the ECB using its asset purchasing scheme to pursue green objectives, we could also see an interesting technical factor at play.

A catalyst for further issuance

How governments spend money is always a political decision. Since green bonds specifically address issues of ethical finance and long-term sustainability, they might help to increase the willingness for an increase in debt levels as a way to stimulate economic growth through investing in environmentally-friendly projects. Therefore, I would expect to see more countries join the current green bond leaders found in France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Chile and Ireland. Apart from Germany, which plans to issue its first green bund via syndication in September this year, Spain and Denmark have also recently shown interest in issuing green bonds. After all, green bonds are a way both to promote environmental objectives and provide economic stimulus.

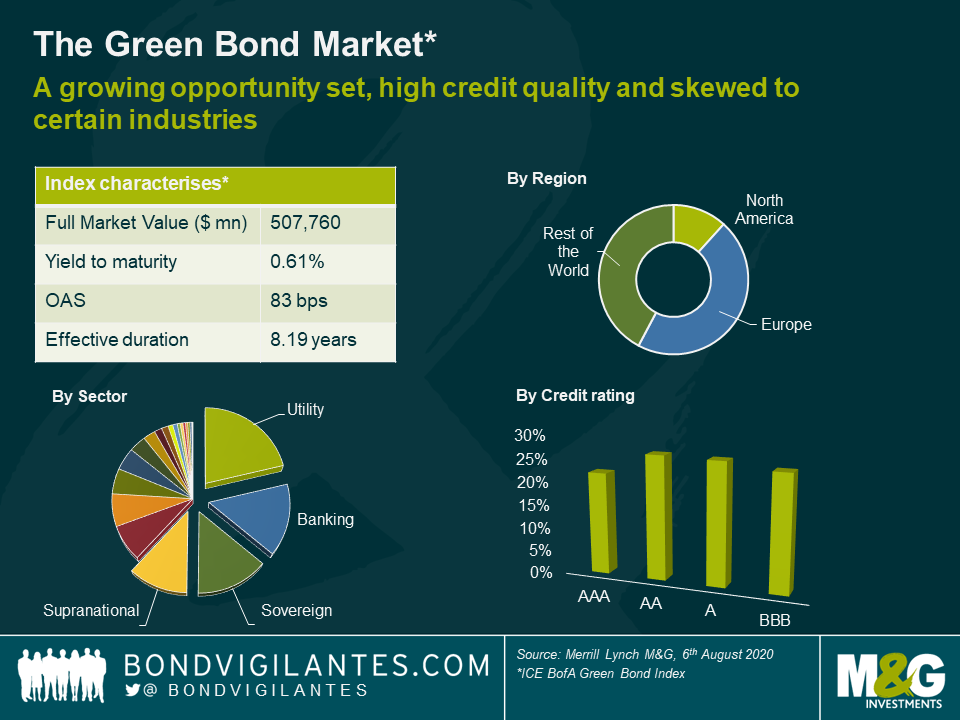

From a bond investor’s perspective however, what is needed is a more diversified green bond market. Taking the Merrill Lynch Green Bond Index as a proxy, the limitations faced in constructing a portfolio come to light (see chart below). Fifty percent of the Green Bond index is rated AA or higher. When looking at the sector breakdown, 49% of the issuers are either sovereigns or quasi-sovereigns, with utilities and banks claiming 21% and 16% of the remaining index weight respectively. The key will be to deepen and diversify the market further. As things stand today, there are still challenges from a risk-return perspective, as it is hard to build a liquid and well-diversified portfolio with sufficient credit risk with only green bonds. Doing a quick Bloomberg search, there are currently only 55 bonds (from 36 issuers) with a high yield Bloomberg composite credit rating.

That said, corporations are becoming more aware of the possibilities that the green bond market offers. Just this year, we have seen BBVA issue its first CoCo green bond. Arguably, this opens up a debate over whether a bond should be used as capital instrument as well as a green-financing tool. In my view, it all comes down to the use of proceeds and transparency, and we can expect the EU taxonomy to provide greater clarity in this area.

We could see green EU bonds as early as 2021

So when will investors be able to integrate the EU green bonds into their portfolios? For now it is hard to say. As far as the Recovery Fund deal is concerned, there are still some hurdles to overcome in the form of parliamentary ratification. Assuming all goes well, the first batch of issuance is scheduled for early 2021, but it is not yet clear whether this will include EU green bonds. Assuming it takes 2-3 months to prepare issuance, we could get more information on this as early as Q4 this year. Before that, the EU may start to issue bonds for the SURE (Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency) programme as soon as September. However, I think it’s unlikely those instruments will be issued as green bonds given that their proceeds will be used to address the immediate challenges of the pandemic, rather than to fund environmentally-friendly projects.

Another point to consider is that the technical working group, which is assisting the EU Commission in the development of the EU taxonomy as well as the EU green bond standard, is still defining the screening criteria for certain segments of the market. Therefore, we might need to wait a bit longer until we see green bonds issued in scale by the EU. Nevertheless, according to Morgan Stanley research, the EU could potentially issue a total of between €800-900 billion by 2025 if all monies were to be fully utilised and disbursed. Part of this new issuance will almost certainly come to market as EU green bonds.

When Ken Ofori-Att – the Ghanaian finance minister – presented mid-year budget revisions, he highlighted the huge challenges of the pandemic. The Ghanaian response to COVID-19 has been quick, well organised and aimed at stopping economic weakness becoming a depression. But the rescue is coming at a large financial cost to the country. The fiscal deficit is forecast to be around 11% of GDP in 2020, while economic growth is expected to slump to 0.9% from a stellar average of 6.8% over the past three years.

While advanced economies and emerging markets with deep domestic debt markets have raised cheap money, many frontier economies have struggled. Like Ghana, they tend to rely more on external borrowing to finance their deficits. Some of this money comes at concessional interest rates from the IMF and multilateral development banks. But for larger volumes, frontier markets have tapped global debt markets. This does not come cheap, even as global investors have searched for yield.

The high cost of borrowing led Ghana’s finance minister, who had a successful career on Wall Street before entering politics, to argue that global capital markets are unfair to African issuers. He argued that “there is no basis for us borrowing at 6%, 7%, or 8% while other countries borrow at cheaper rates”.

Is there an ‘Africa premium’ on global debt markets?

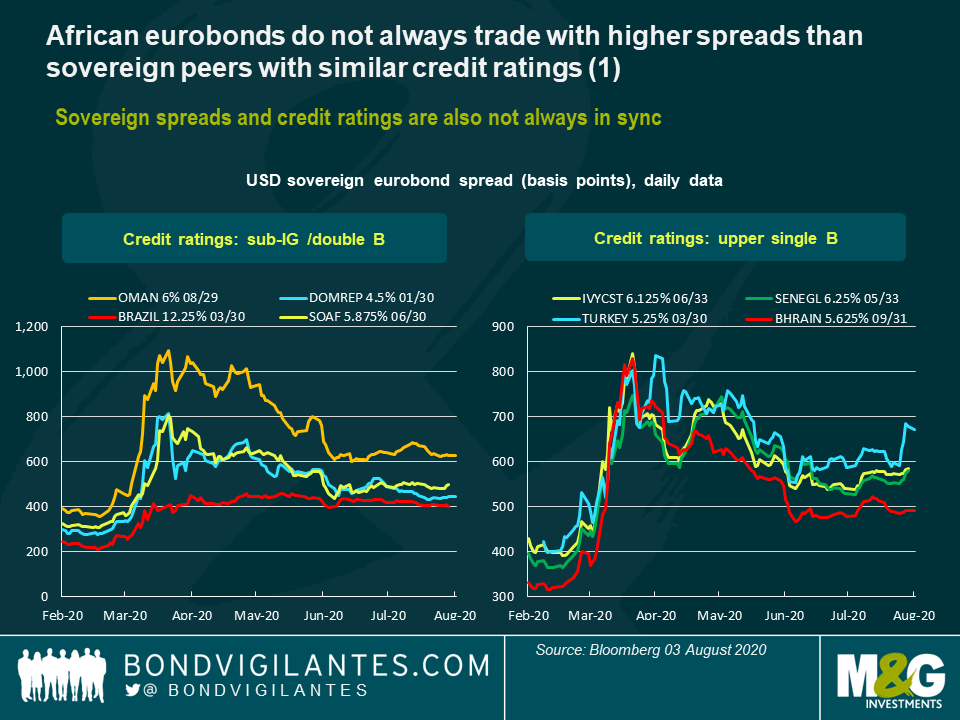

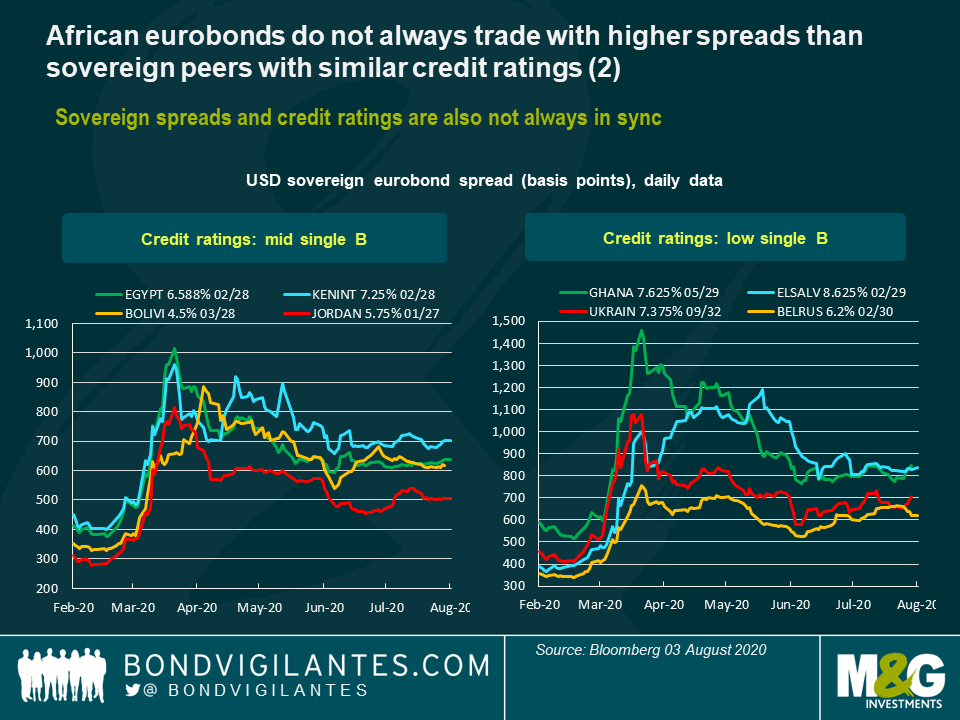

Three methods are used to evaluate any unfairness. First, specific African bonds can be compared to those of similar maturities from emerging market peers with similar credit ratings.

- Compare specific African bonds to EM peers with similar maturity

Here the results are varied and depend on which comparison is made. For example, you can compare a 10-year USD South African eurobond with one from Brazil. Despite similar credit ratings, Brazil-30s have a spread (over US Treasuries) of around 305 basis points, while the spread on South Africa-30s is around 486 basis points. However, South Africa-30s trade better than Oman-30 – also with a similar credit rating – which have a spread of over 600 basis points. Similarly, in a higher single-B credit rating category, Senegal and Ivory Coast trade better than Turkey but worse than Bahrain. And in a lower single-B credit rating bucket, Ghana trades with a higher spread than El Salvador, Ukraine and Belarus. In these cases market pricing might be out of sync with the credit ratings, or the credit rating might be out of synch with the sovereigns. But neither is ever a perfect guide to debt sustainability. These comparisons justify why Ghana’s finance minister raised this issue, but fall short of confirming any systematic unfairness across African sovereigns.

2. Compare spreads of a larger sample of eurobonds

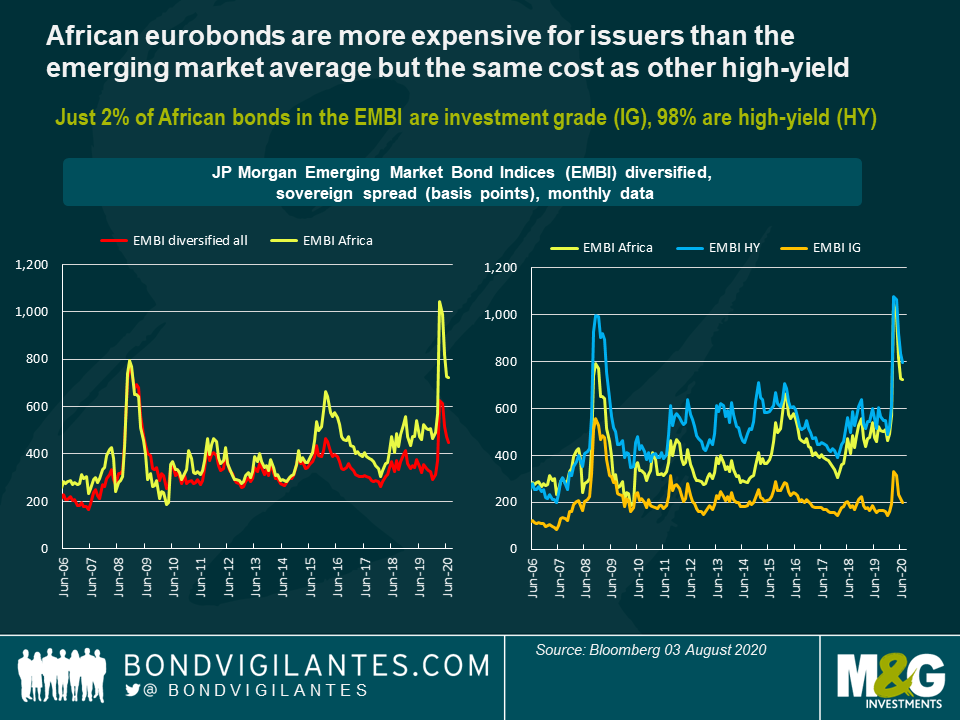

The second method is to compare the spreads of eurobonds across a larger sample. Between 2006 and 2015, African eurobonds in JP Morgan’s emerging market diversified bond index (EMBI diversified), had similar spreads to the index average, including during the global financial crisis. However, since late 2016, African eurobonds have traded with a premium. And during this crisis, this spread premium for African issuers has increased dramatically relative to the full index average. The shift since 2016 is to do with increased sub-investment grade issuance by African sovereigns over the past 7 years, which has helped grow the stock of African eurobonds to $121 billion from 20 issuers.

Only 2% of African eurobonds in the EMBI diversified have investment grade credit ratings (just Morocco’s), compared to an index average of 54%, providing some justification for higher African spreads. So a more meaningful comparison is between African eurobonds and other high yield emerging market eurobonds (also with sub-investment grade credit ratings). Once the credit ratings of the issuing sovereigns are accounted for, a premium is less easily identified.

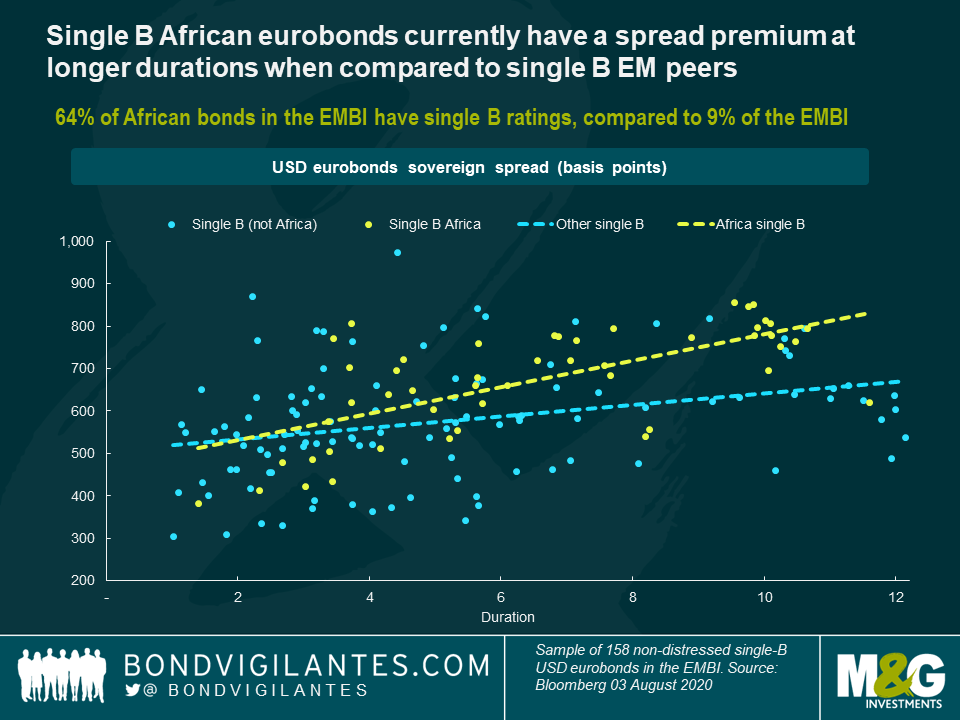

3. Focus on non-distressed eurobonds

The third method is to focus on a sample of non-distressed eurobonds with the same credit rating to allow for the varying durations of emerging market bonds. A sample of 158 single-B USD eurobonds is plotted, including 49 from African issuers. Here the analysis suggests a higher spread for longer-duration African eurobonds. While debt risks have increased during the 2020 crisis, this does not explain why African duration is doing less well than other single-B duration. One factor weighing more on African sovereigns might be the frequent G20 calls for debt service suspension.

Are the calls for debt suspension keeping African eurobond spreads higher?

Of the 17 countries in the EMBI that are eligible to apply for the G20 debt service suspension initiative, ten are African¹. In many cases the calls for a debt service suspension, or deeper debt relief, are justified by the huge pressure that lower-income countries are facing in 2020. But they also have undermined confidence that debts will be repaid in full, even for countries with market access and no clear debt problems.

There are 64 non-distressed USD sovereign eurobonds that have been issued by countries eligible for the G20 debt suspension initiative. When the spreads of these bonds are compared to a benchmark of bonds not eligible for the initiative, in this case Egypt’s eurobond curve, there is currently a spread premium of around 100 basis points. This spread premium could reflect the uncertainty of whether eligible sovereigns will suspend coupon payments on eurobonds, in line with the G20’s advice. This concern exists despite half of the eligible and EMBI included sovereigns refusing the initiative and, of those requesting it, most stressing that they seek only bilateral debt service suspension. Interestingly though, further analysis of the spread premium shows that it persists whether or not an eligible country has accepted or rejected the initiative.

Conclusion

The Ghanaian finance minister should be frustrated that they pay more to borrow than similar-rated sovereigns from other regions. But once credit ratings are accounted for, there does not appear to be a persistent higher cost of borrowing for African issuers. This suggests reforms, economic growth and reduced debt risks will be needed to improve credit ratings and reduce relative borrowing costs—or improved credit ratings metrics if it is evidenced that they over-state African risks.

Nonetheless, there is currently a higher spread for long duration African eurobonds. This may be linked to uncertainty about the debt suspension initiatives. Greater certainty on the extent of the suspensions might close this gap in 2020. But there are also other uncertainties in play, including whether specific countries are facing liquidity or solvency problems as a result of the 2020 crisis.

An in-depth understanding of the varying risks being faced across African and frontier sovereigns is going to be essential for investor strategy in the remainder of 2020 and in 2021. As data for the second and third quarter of 2020 is released, differentiated market judgments will result as the debt scars of the crisis become easier to measure.

¹ DSSI eligible countries in the EMBI include: Angola, Cameroon, Ethiopia, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Kenya, Mozambique, Nigeria, Senegal, and Zambia from Africa. Plus Honduras, Mongolia, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, Sri Lanka, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan from elsewhere.