In this 15-minute interview I ask M&G’s Greg Smith, an emerging market debt strategist with a speciality in Africa and formerly a World Bank economist in Zambia, how the continent is coping with the Covid-19 pandemic. We also discuss how worried we should be about the negative headlines coming out of the region over Zambia’s recent default on its international bonds. Is this the start of a wider trend in African defaults? And how is Chinese state power manifesting itself in lending and recoveries in the region?

We didn’t get the chance to discuss it in the video, but afterwards Greg talked of his sadness that Ethiopia is once again at war. A year ago Ethiopia’s Prime Minister won the Nobel Peace Prize for ending Ethiopia’s war with Eritrea. Today the region of Tigray appears to be the centre of some significant military activity, and there are fears for the 500,000 citizens in its capital.

We also discussed the sad fact that Africa usually appears in the news only when bad things happen – debt default, famine or unrest. In the video, Greg points out that emerging market defaults have been lower in Africa than elsewhere to date, and that actually Africa’s Covid experience has in many ways been less severe than that of many other regions – probably because of the much lower average age of populations.

The background to Wednesday’s announcement

In line with market consensus, on Wednesday the government announced that RPI would be made into CPIH, a lower number. This is not being done for political reasons by the Chancellor, but for statistical ones.

As I have written about previously the national statistician has made clear for years that it does not like RPI, and that it has been frustrated at being unable to reform the methodology around its calculations (to make it a lower, more accurate reflection of inflation) because of the need to get approval from the Chancellor. It is worth remembering that the statistician consulted on abolishing RPI in 2012, and has since de-recognised it as a national statistic as it does not see it as fit for purpose. The statistician gets control of the issue when the UK 4.125% 2030 linker matures. In this way the government can present the decision as a passive one, made by the statistician and not the Chancellor.

The decision

This announcement makes clear, at long last, that RPI will be the same number as CPIH from 2030 onwards. This number will be approximately 0.8 percentage points lower over the medium term than it is in under its present calculation. If we assume that nominal gilt yields are unaffected by this, it means that RPI breakevens will need to fall by around this amount from 2030 onwards. That means that real yields need to rise, and breakevens to fall, by around 0.8 from 2030 onwards. The government announcement says in bold “The government will not offer compensation to the holders of index-linked gilts”.

Market impact

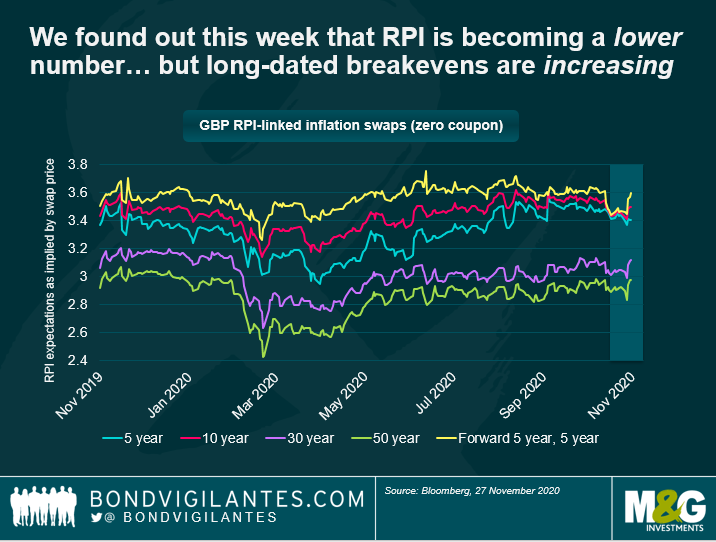

Given that the market expected this outcome by and large, why did we see meaningful moves in linkers and breakevens on Wednesday? And are they moving as we would expect, given the above?

The biggest increases in breakevens are being seen in the 5y to 10yr part of the curve (yellow line below). This is because there was significant nervousness that, given the huge borrowing brought on by the pandemic and the dire state of the fiscal deficit, the Chancellor might be prepared to make this reform political and accelerate its implementation date to 2025. On Wednesday he announced he would not do that, and so the bonds in this part of the curve are rallying.

Secondly, and most striking to me: longer dated breakevens and real yield are not selling off massively but are in fact rallying. The fact that the market was expecting this outcome, with breakevens having started to move somewhat lower in recent times to reflect this, does not even start to explain this: the market is moving in a counter-intuitive way and counter to what I would expect. Breakevens shouldn’t be moving significantly higher, but should be moving lower, perhaps by 50bps to 70bps. Clearly there’s a long time left before the longer-dated bonds mature, with lots of inflation cycles and potentially much higher inflation to come in the future, maybe even with CPIH being between 2.75% and 3%. But given Wednesday’s news, and the disinflationary spot we still find ourselves in, the pricing of breakevens now looks on the expensive side to me.

Maybe some think that they will be able to claim compensation for the change from the government? We found out on Wednesday that none will be paid. Perhaps some will try to litigate? Given the changes are statistical, not political, I think this is a pipe dream too. Perhaps the market was waiting for a weak day to buy inflation protection and lots of traders pressed the button on Wednesday? There is plenty of appetite for linkers from pension funds, and those which were underhedged on inflation will have seen their funding ratios increase. Perhaps that is the best explanation for the rally: with limited inflation-linked issuance, they have not hung around. And there may be plenty of less-price-sensitive, liability-driven funds too which were short of breakevens and, with the RPI uncertainty removed, have now moved in. Still, I would not have expected this demand to come so early: I anticipated a significant downward repricing first.

There is also the possibility that the market is pricing in a more bullish view on the housing market, which is currently very strong, and that this is leading to a higher outlook for CPIH. Even so, the moves on Wednesday were surprising and make UK breakevens look on the expensive side for now – that is, until it becomes clear that we are in a cyclical upturn, with loose monetary policy and continued loose fiscal policy, and perhaps a new average inflation targeting regime.

So, the changes to make RPI a lower number have been approved, to come into effect as anticipated by most in 2030. This should, fundamentally, lead to higher real yields and lower breakevens post implementation. In the long end, I would have anticipated fairly significant moves on Wednesday, in the exact opposite direction from those which we saw.

Inflation valuations

There are plenty of factors in the mix to make me bullish on a medium-term reflation scenario in the UK: this time round, we have fiscal and monetary policy working together to stimulate the economy (unlike in the aftermath of the GFC, when policies of austerity led to a fiscal tightening); given the country’s debt burden, it seems reasonable to expect central banks to allow inflation to run a little hot; and the risk of a weaker sterling after Brexit brings the possibility of further imported inflation. Fundamentally though, it feels to me like inflation expectations both in swaps and in breakevens are on the rich side of fair value given that inflation is running low for now, and that the pandemic leaves us all in a more disinflationary spot than anything else, at least in the next 6 to 12 months. There is also a possibility of the return of austerity in 2021, which would risk a more persistent disinflation than the one we are in today.

I expect breakevens to cheapen up in the not too distant future, particularly if we see further linker supply in the next quarter, but anticipate some volatility. Based on these valuations, I think there will be better opportunities to enter into the reflation trade then.

The dramatic rally in US high yield bonds since the end of September saw yields reach lows of 4.6% earlier this month, the US high yield index’s lowest level since 2000. Yields have risen modestly since then but remain very tight: 4.9% at the time of this writing. The US high yield bond spread over risk-free government bonds has narrowed close to its pre-Covid level (see chart below), a trend which has accelerated over the last few weeks following the US election result and news of positive vaccine trials. Both pieces of news had a dramatic effect across high yield markets.

The biggest reaction was concentrated in Covid-sensitive issuers such as airlines, cruise lines and casinos, but the news was also felt more broadly across the asset class: 29 out of 32 US high yield sectors were trading with spreads higher than their pre-Covid levels at 30 September; now that figure is just 15. Issuers within the energy and healthcare sectors were notable beneficiaries of the election outcome as the threat of a “blue wave” subsided. President-elect Biden’s legislative programme, which included healthcare reform, clean/renewable energy proposals and potential restrictions on drilling on federal land, will have a hard time getting through a divided Congress.

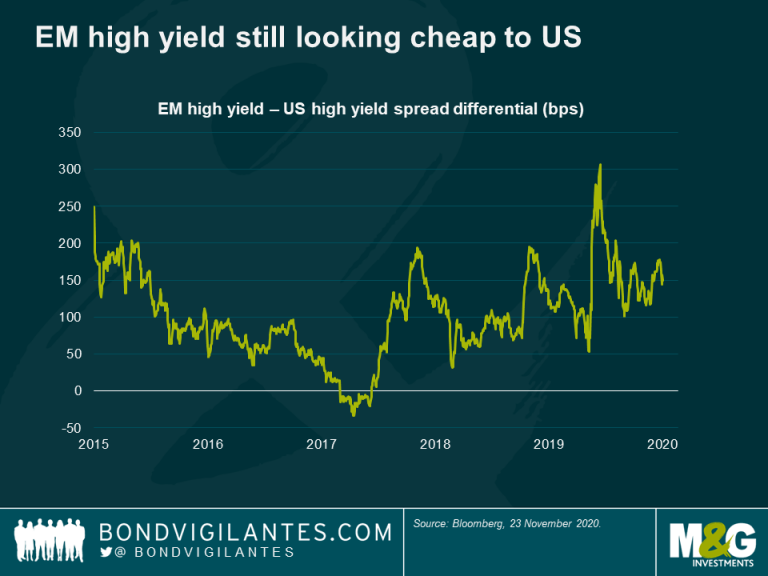

In credit spread terms, the US high yield market is now looking expensive relative to its peers in Europe and emerging markets. Emerging market high yield in particular still offers some value in my opinion. Here, high yield spreads remain elevated versus the US due in part to the weaker central bank firepower available in emerging markets. The chart below highlights the current spread pickup for investing in EM high yield versus US high yield.

Looking at the overall picture of global high yield credit, most investors would agree that valuations now look expensive compared to historical levels, especially given the backdrop of dramatically rising infections in the US and the threat of stricter lockdowns and rising unemployment everywhere else.

Even after the rally, there remain several powerful supportive technical factors which high yield investors ignore at their peril. Demand for higher-yielding debt remains robust and the asset class is experiencing strong fund flows (albeit lower than in investment grade). A further tailwind is the supply of new issuance, which now looks relatively constrained following a record-setting summer of issuance as companies built up liquidity buffers and refinanced debts, leaving a more limited forward issuance calendar. The loan market has also seen a resurgence, which is taking borrowers away from the bond markets and further constraining supply. We must also remember that $171bn of investment grade bonds fell into the US high yield market after being downgraded by the rating agencies. These so-called fallen angels expanded the index by 21% and are (by-and-large) higher quality than average, which supports tighter spreads.

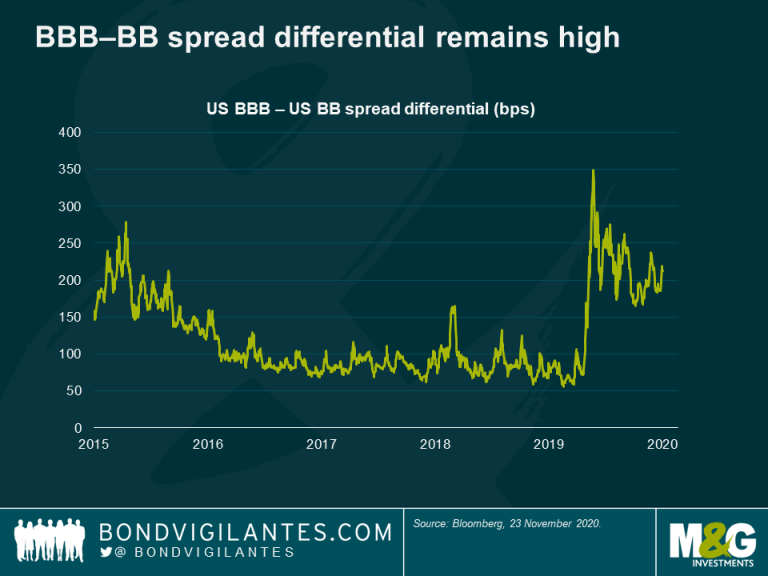

Also, while valuations might be difficult for high yield fund managers to stomach at the moment, the asset class still offers a degree of relative value. For example, while the spread differential between BBBs and BBs has compressed somewhat since the peak of the crisis, it is still materially wide versus historical levels (see chart below). In a world of $17 trillion of negative-yielding bonds, the 4-5% yield offered by high yield can look attractive to investors outside the traditional investor base, potentially drawing more participants to the market and leading to further spread tightening.

Lastly, the U.S. government (however divided) and the Federal Reserve proved over the spring and summer that they are prepared to do “whatever it takes” to support the economy and markets. From massive fiscal stimulus to bond purchases (including high yield), they provided enormous support which has helped businesses survive and markets recover. There is some concern about whether there will be another round of stimulus given a still-divided Congress. However, I am of the mindset that further support and stimulus will be delivered if it proves necessary on the back of accelerating lockdowns. The size and scope of the stimulus will be debated, but I believe that none of the current president, the president-elect, the Senate or the House will want to “own” the stimulus not being done and have a side-lining of the recovery on their shoulders.

The current environment poses a dilemma for high yield investors given tight valuations with the backdrop of the ongoing pandemic and resulting economic turmoil, with the prospect of more damage to come. Do they de-risk in light of these pending threats and ignore the strong technical forces noted above, potentially missing out on the continued rally? Do they de-risk anyway on expectations that, despite strong technicals, the market has come too far too fast and is due a correction after which they can reinvest? Or do they rotate into Covid-exposed names such as airlines and leisure companies where bonds have rallied but are still meaningfully cheaper than before the crisis, banking on the success of the vaccines and a near-term return to normality?

My belief is that technical factors will probably dominate the less attractive valuations from here. Yes, there are obvious risks to the downside but, as we learned over the summer, the technical forces mentioned above (federal stimulus in particular) are too strong to ignore. The greater risk in my view is not to be invested in a high-yielding, income-producing asset class with a stimulus-lined path out of the Covid crisis that is now clearer than before. In the meantime, as always, there are single names and sectors that have run too far in my view (e.g. gaming) and sectors too that are now much more investible (e.g. airlines) but, for the high yield market in general, there could well be further upside form here.

The Covid-19 crisis has been a very different recession in a number of ways. One that I think is particularly interesting is the role of banks. While it is a vast oversimplification, ask ten people what caused the great financial crisis, and nine will answer “the banks!”.

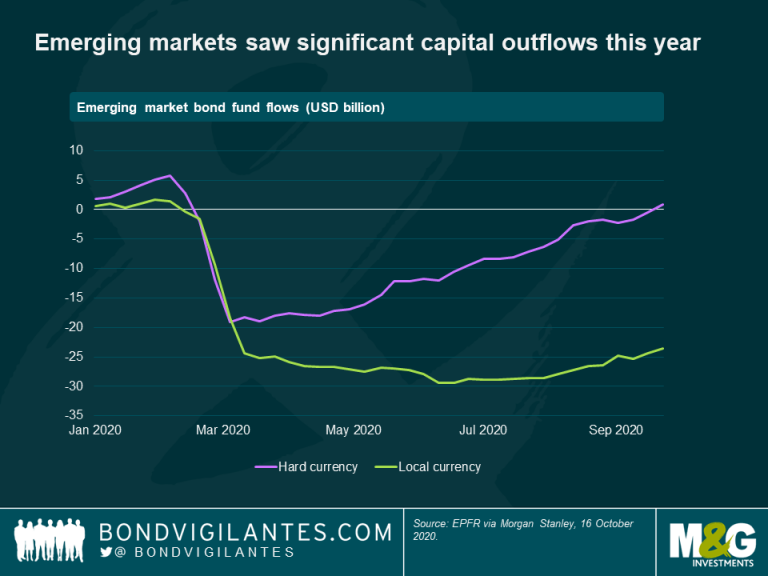

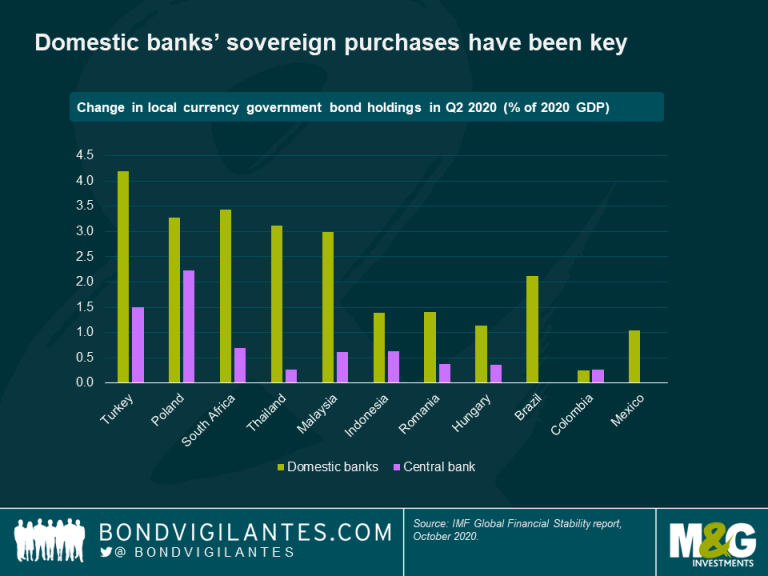

This time round, it has been the commercial banks that have helped many economies to remain functioning. Nowhere is that truer than in emerging markets. In the worst of the liquidity crisis at the start of the year when emerging market (EM) governments needed to issue new debt, many foreign investors—usually one of the large sources of financing for EM economies—exited the market as the virus started spreading globally and major risk aversion took hold. This resulted in significant outflows of capital, especially from the local currency bond markets where flows remain deeply negative to this day (still down by around $23 billion – see chart below).

In a blog earlier this year, I described how many emerging market central banks followed in the footsteps of developed market banks and initiated some form of quantitative easing (QE) in response to the challenges of increased budget deficits and a lack of foreign investment. I also touched on the risks that these programmes posed on the future credibility of EM central banks and their local markets. Several months later, it is interesting to note that most central banks have in practice remained very conservative in their approach to direct sovereign bond purchases.

There have been a few exceptions, such as the Philippine central bank, which bought more than 80% of the country’s net sovereign bond issuance year to date. Likewise, the Polish, Indonesian and Israeli central banks all purchased around 50% of their sovereign net issuance. For other economies however, central banks have been far more restrained and bought on average less than 10% of the net issuance this year. This has been in large part thanks to local commercial banks which stepped up and purchased significant amounts of sovereign debt, absorbing as much as two-thirds of net local currency bond issuance year to date according to Deutsche Bank.

Local commercial banks’ involvement in local sovereign debt markets has been driven by several factors. While governments have in many cases increased incentives for banks to purchase sovereign debt, it has been largely driven by economic rationale.

First, the gap between deposit and loan growth increased sharply this year. Deposits increased as a result of precautionary savings, less spending and fiscal transfers, while demand for new loans collapsed as economies entered into recession. This created space on bank balance sheets to buy more sovereign bonds. Banks also likely became less willing to extend credit to private borrowers as the risk of default increased, making sovereign bonds’ higher credit quality an appealing feature.

Relatively steep government bond curves provided a further economic incentive for bank to buy sovereign bonds. As bank funding costs generally tracked policy rates, steep curves provided an attractive carry pick up. The potential for duration gains from falling yields as central banks were cutting rates provided additional upside.

Government policy was also an important factor, and several measures were designed specifically to increase local bank demand for sovereign bonds, reducing the need for central banks to intervene. Indeed, many central banks remain reluctant to engage in significant QE operations, particularly in regions and countries where previous monetary crises serve as a reminder of the importance of central bank independence – the Mexican and Brazilian central banks notably did not engage in QE at all.

Cuts to reserve requirements have been widely used too in order to encourage commercial banks to purchase sovereign bonds. They were explicitly linked to increasing bond holdings in some cases, such as in Malaysia and Indonesia, where in the latter a private placement of IDR 105 trillion of sovereign bonds was organised to coincide with the time of the reserve requirement change. Generous liquidity provisions for the purchase of sovereign bonds were also implemented in many countries, encouraging the carry trade.

Finally changes in accounting rules, allowing for more favourable treatment of sovereign bonds by easing mark-to-market rules, also played a role. For example, Russia allowed banks to mark purchases at their market price on the 1st of March, even if they had bought them after that date. In the third quarter, Russia also decided to issue floating rate bonds, which are typically held by local banks and not by foreign investors.

Local commercial banks provided an essential backstop for local sovereign debt markets in 2020. Their significant involvement allowed governments to issue debt at reasonable costs, and to finance their deficits at a critical time when foreign investors were on the side-lines. Importantly, it allowed central banks to limit their interventions in most EM countries, safeguarding their hard-earned credibility while ultimately having a similar effect to central bank QE.

While I think this has been a positive trend, this situation also raises potential risks down the line. It is increasing the interdependence between the banks (which are financing governments) and those governments (which are expected to recapitalise banks in case of a crisis). Potential concerns over government debt sustainability in the future could lead to worries over banks’ balance sheet in a vicious circle, reminiscent of the eurozone crisis in 2010. Furthermore, the main difference between commercial banks’ purchases and central banks’ QE is the economic rationale – commercial banks are profit-driven. Their appetite for sovereign bonds this year has been a function of the low funding costs available and the carry opportunities offered by sovereign bonds. If inflation were to return in a meaningful way, forcing central banks to hike front-end rates, the rationale for these investments would disappear and local banks would likely reduce or stop their investments in sovereign bonds, leading to potential volatility for emerging market bonds.