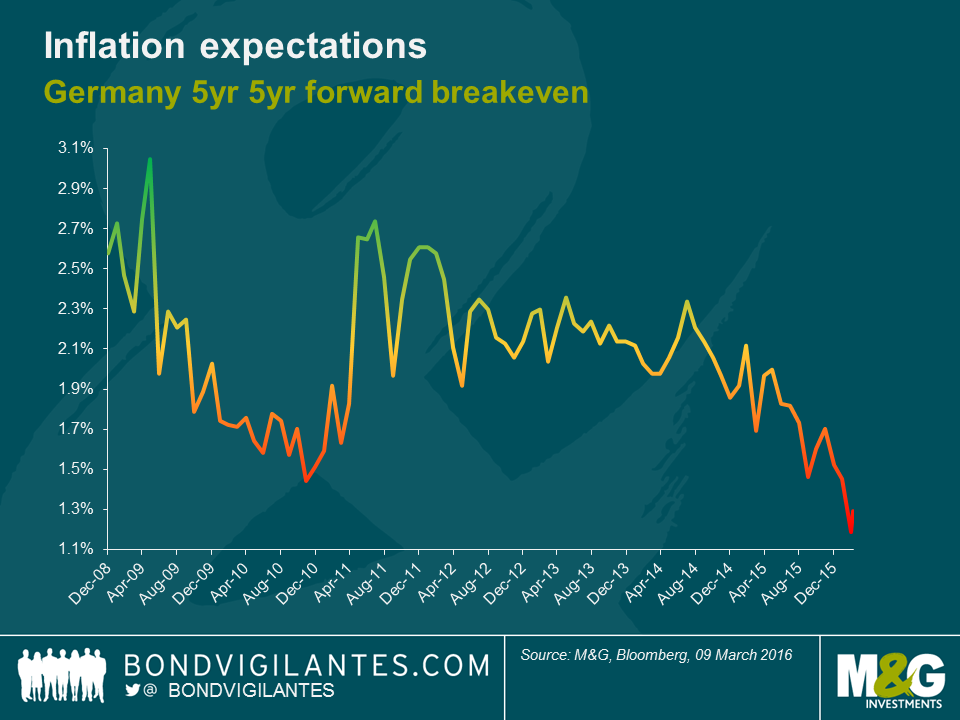

The simple answer is a no. Eric Lonergan in a guest blog has already (see here) debunked the idea that central banks are at the zero bound. And since then the market has become increasingly confident that the ECB will cut its deposit rate further into negative territory at tomorrow’s meeting. And it has reason to do so. Inflation and growth will be lower than the Bank had forecast a mere three months ago with inflation expectations also falling out of bed.

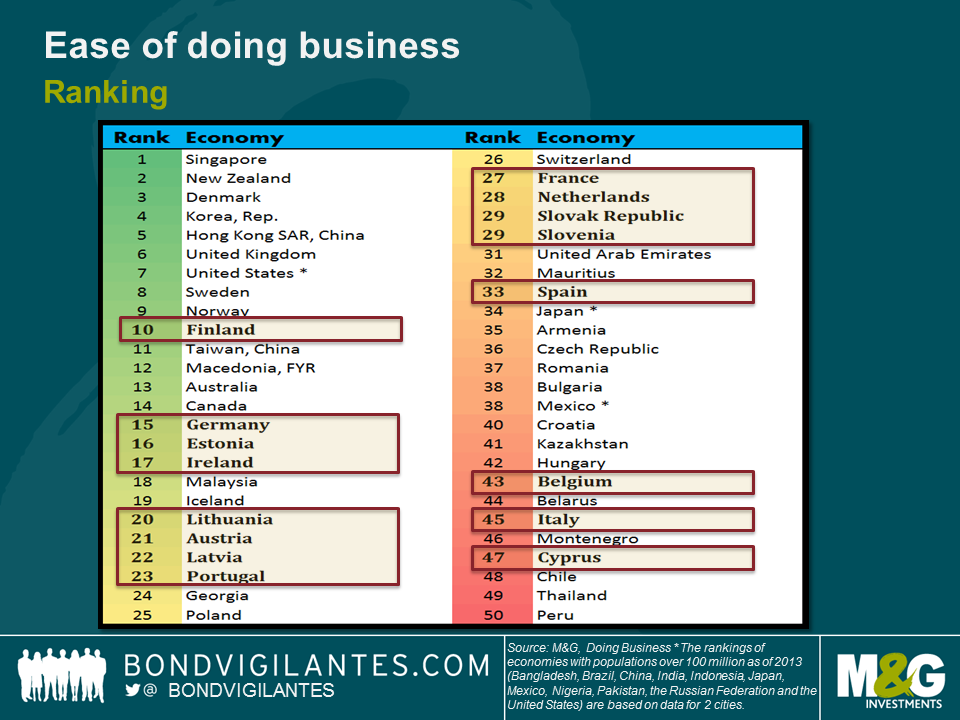

But that isn’t to say that there aren’t diminishing returns to be had from a further loosening of policy. The reality is that many of the problems holding back the Eurozone are structural in nature. And doesn’t the ECB know it. I can hardly remember a press conference when Mario Draghi hasn’t failed to mention the need to address these issues. Hardly surprising given that the Eurozone is only represented twice in World Bank’s top fifteen ‘Ease of doing business survey’. The likes of France at 27, Spain at 33, Italy at 45 and Greece at 60 makes for painful reading.

The ECB is acutely aware of the moral hazard it creates in addressing the Eurozone’s troubles purely via the monetary channel. And yet with a sole mandate to hit an inflation target of close to but below 2%, they are once again finding themselves with the unenviable task of having to do the bulk of the heavy lifting. On Thursday we will likely see a cut to the deposit rate with some sort of tiering in an attempt to address some of the challenges faced by the banking system (see Mario’s blog post), as well as an extension to the PSPP (QE programme), both in terms of size and duration. We may even see a greater willingness to buy certain corporate bonds – although this will likely be a step too far for the majority on the Governing Council.

But the reality is that increased productivity and greater innovation is much needed to drive the Eurozone. Antiquated bankruptcy regimes need to be radically reformed, red tape needs to be removed and the banking system needs to own up to further loan losses that it has yet to provision for. These changes aren’t easily achieved, not least because they require the sort of short term pain that politicians rarely have long run incentives to deliver.

Consider the case of Italy. Since the global financial crisis the Italian housing market has fallen in value by around 19% from its peak. This, combined with recessions that have left Italian GDP around 10% lower than in 2008 and rises in unemployment to around 12%, have conspired to create a large amount of c. €200Bn of non-performing loans (NPL’s) in Italy as households and companies have encountered difficulties in servicing their debt.

Unlike in other Eurozone periphery countries such as Portugal and Spain, Italy has been slow in restructuring its banks and addressing the problem with many NPLs still sitting on banks’ balance sheets. The Italian banking system is therefore considered to be weak and there have been a wave of recent high profile bank collapses that have resulted in ‘bail-ins’. With this in mind the Italian authorities have just set up a scheme to create Asset Management Companies who will then look to securitize these non-performing loans, in theory reducing a bank’s balance sheet and allowing them greater scope to lend to the broader economy. As the scheme is very much in its infancy we will have to wait to see whether it can have the desired effect.

Absent further structural change I’m convinced the Eurozone will labour under a cloak of lower potential growth and struggle to encourage investment given the need to earn an attractive rate of return on capital. Yes the ECB can likely drive risk-free rates even lower. Yes they can depreciate the €. And yes they can provide ever more liquidity to the banking system. These may all help near term. But without real reform the market will increasingly worry that we have reached the limits of monetary policy. And at some point if the market cannot be convinced otherwise, then the consequences will be significant.

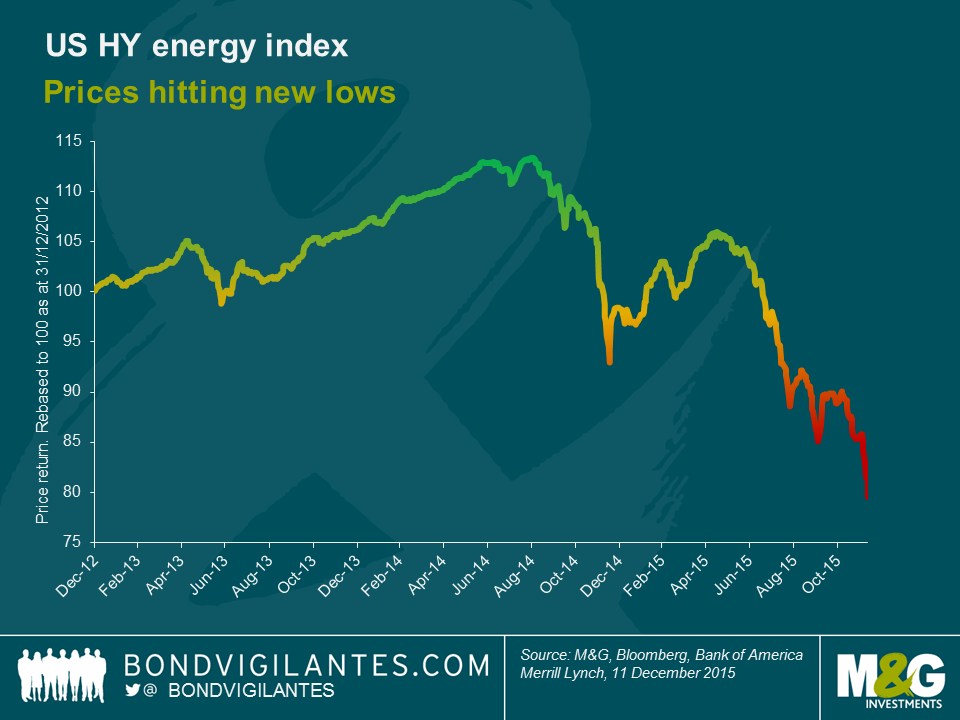

2009 through 2013 were some very good years for the US high yield market. And the energy subset was no exception. Returning 51%, 13%, 9%, 12% & 6% in each of those years, it’s not surprising that the BofA Merrill Lynch US High Yield Energy Index practically trebled in size. Voracious issuance, much of it to fund shale oil development, was met with equally intense buy-side demand and with it came the all too familiar weakening of covenants.

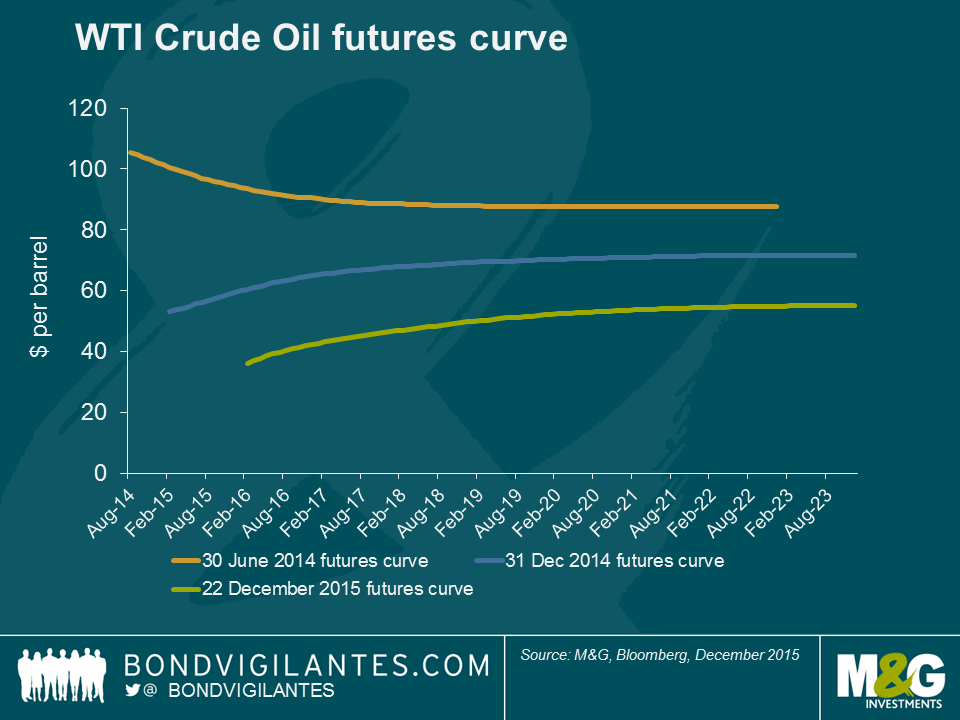

But after a number of golden years, the energy market began to fall out of bed in 2014. Expectations of weaker global demand, especially from the Far East, coupled with a supply glut and a stronger US Dollar saw a radical reappraisal of the future prospects for prices.

It’s easy to forget that back in mid-2014, only some 18 months ago, WTI was priced to sell for around $88 five years forward. By the end of that year that number had fallen to $70, and now the same figure looks set to finish 2015 around 51 bucks.

Such a rapid reappraisal of the future value of oil and gas has had drastic consequences, especially for the most levered of producers. And with little expectation of a significant recovery in prices, the focus has turned to liquidity and its management via distressed exchanges.

Distressed exchanges, defined by Moody’s as an offer to creditors of ‘new or restructured debt, or a new package of securities, cash or assets, that amounts to a diminished financial obligation,’ became a notable feature of 2015. We count at least eleven significant exchanges during 2015.

The latest and perhaps most significant has come from Chesapeake Energy. Collapsing natural gas prices and little prospect of attracting equity capital has left the company with a looming liquidity crunch. In response, Chesapeake offered earlier this month to exchange up to $3bn of their unsecured liabilities for second lien secured debt, with bondholders accepting a write-down on their existing claims. So in a nutshell, the company reduces its debt load in return for offering some security over its asset base.

Which immediately begs a number of questions. What’s in it for the company? What does it mean for its stakeholders, especially investors in the company’s bonds? And finally, is this exchange enough to ‘right size’ the company’s balance sheet?

Having seen the yield on its five year debt rocket towards 50% during the second half of the year (see chart below), Chesapeake has little prospect of refinancing over $1.5bn of bonds that come due in the next eighteen months. The company does, however, have significant room to incur secured debt. By offering to exchange near-term maturities into longer dated debt, as well as asking bondholders to accept a write down on their claims, the company is able to reduce its liabilities and buy precious time whilst praying for a recovery in gas prices.

The outcome for stakeholders, especially bondholders, is less straight forward. Without going into the detailed mechanics of the exchange, it is difficult to opine on the best course of action without the benefit of hindsight. At its core, and this is true of most of these exchanges, bondholders must weigh the future prospects for the business versus the variety of options put to them by the company and the costs involved. Given the outcomes are many and uncertain; the decision process is far from straightforward.

Ultimately, whether the exchange offered by Chesapeake –and the dozen or so others we have seen this year– serve to sufficiently right size the balance sheet, only time will tell. What we can be sure of is that distressed exchanges and financial engineering is a likely feature of 2016.

The temptation to ‘juice-up’ shareholder returns with low yielding corporate debt has been too much to bear for many companies and their investors in recent years. This fad has been well documented and though it may not be a trend we creditors like to observe, we haven’t been entirely surprised to see it play out in 2015 given the seemingly large valuation disconnect between the cost of debt and equity; even if the comparison is often far too simplistic.

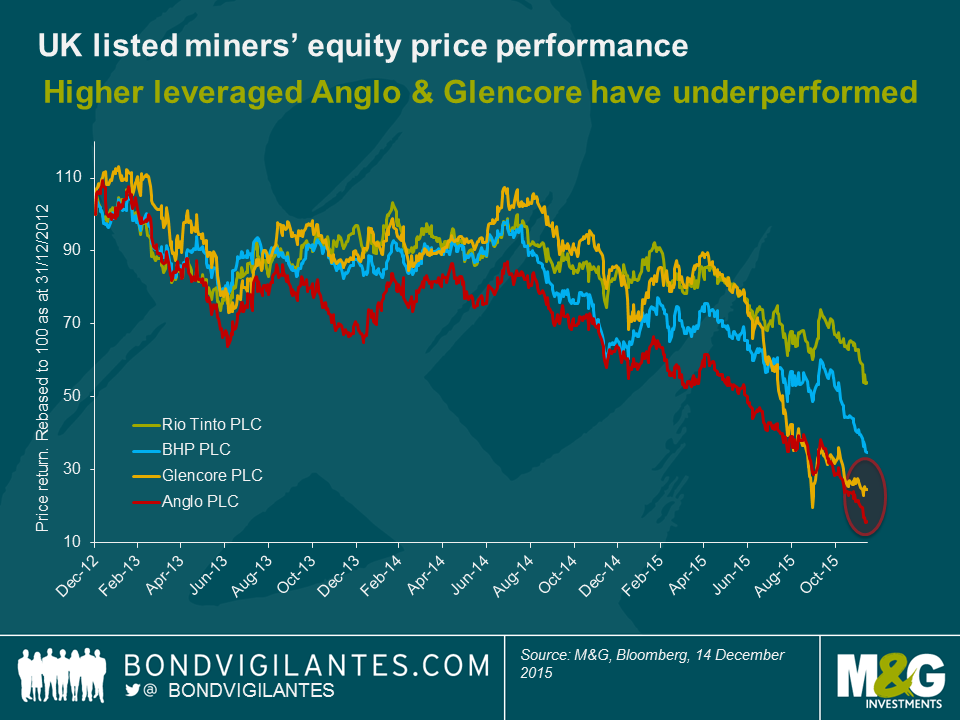

But having taken on more debt, and despite often doing so at record low yields, this has not translated into a winning strategy in 2015. Take the example of the four UK listed mining majors – Anglo American, BHP, Glencore & Rio Tinto. Back in March/April of this year Anglo was able to borrow five year € money at 1.5% and Glencore at 1.25%. Although earnings and hence equity prices had already come under pressure by Q1 2015, bond markets appeared somewhat sanguine.

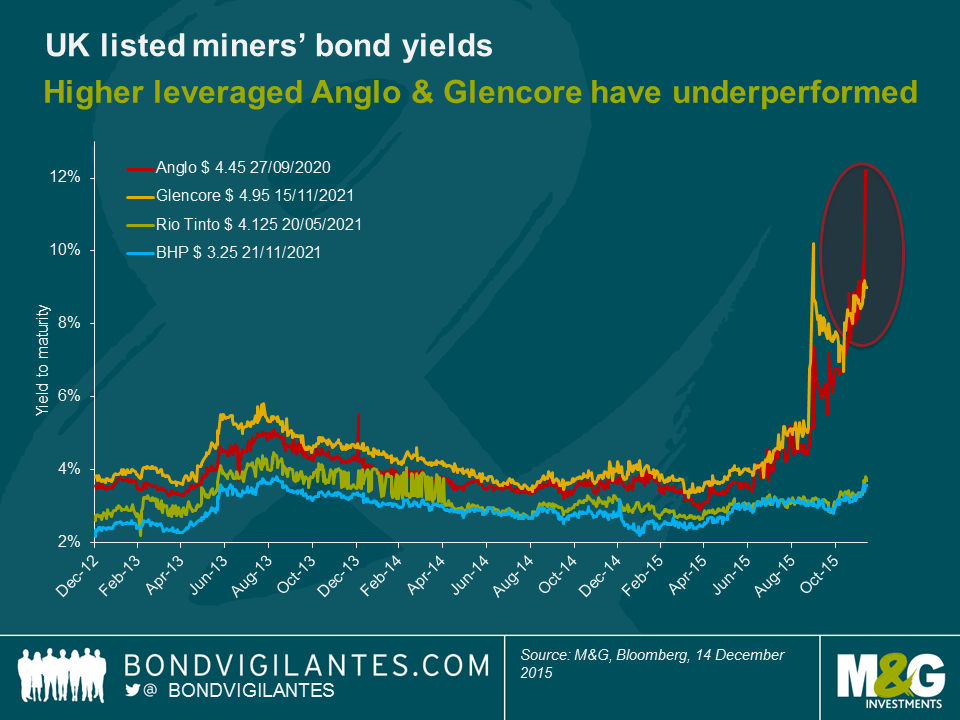

But it has been tough going since then. Whilst all four miners have continued to see share price falls through 2015, the underperformance has been stark for the more levered & lower rated Anglo American (Baa3/BBB-) and Glencore (Baa2/BBB).

And the same relationship can be observed in bond markets. Spooked in part by the more aggressive financial policies followed by Anglo & Glencore (at June ‘15 their ratio of net debt to EBITDA was 2.2x & 2.7x) their five year $ funding jumped from 4% to approximately 9% and 12% respectively. Higher rated Rio (A3/A-) and BHP (A1/A+), both with much lower ratios of net debt/EBITDA, saw a far smaller move higher in yields from 3.2% to 3.7% and 2.8% to 3.7%.

In fact, things had got so bad by the second half of 2015 that both Glencore and Anglo were forced into something of a ‘U-turn’, announcing plans to focus on debt reduction, an equity raise, asset sales, and dividend suspension for Glencore, and major operational restructuring and dividend suspension for Anglo (Anglo has so far avoided issuing more equity but the pressure remains). Suddenly, the interests of bond holders and shareholders seemed very much aligned, with investors questioning the wisdom of running so much financial leverage, scrutinising the quality of assets and cash flow generation – bondholders especially demanding answers.

But nowhere has the risks of leverage and cyclicality been more evident than the recent experiences of the US high yield market. Having funded much of the recent shale oil & gas revolution, US high yield investors are nursing serious wounds. With oil prices almost half of where they were earlier in the year, both bondholders & shareholders are sitting on large losses as we head into 2016, with the prospect of further restructurings to come.

It seems clear that debt and equity investors alike should continue to question just how well a cyclical industry lends itself to heavy indebtedness. By their nature, cyclical industries will always be exactly that – cyclical. Debt may very well be a mainstay of a company’s balance sheet today, allowing for growth and investment, but it is rarely a panacea for an underperforming share price. We should be wary of any company that treats it as such.

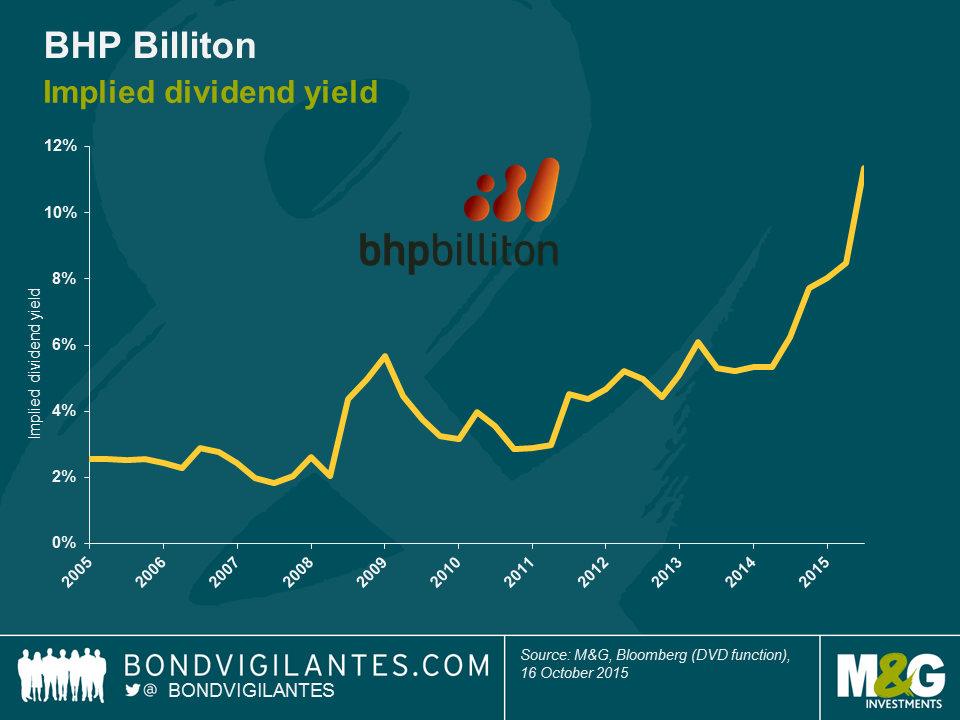

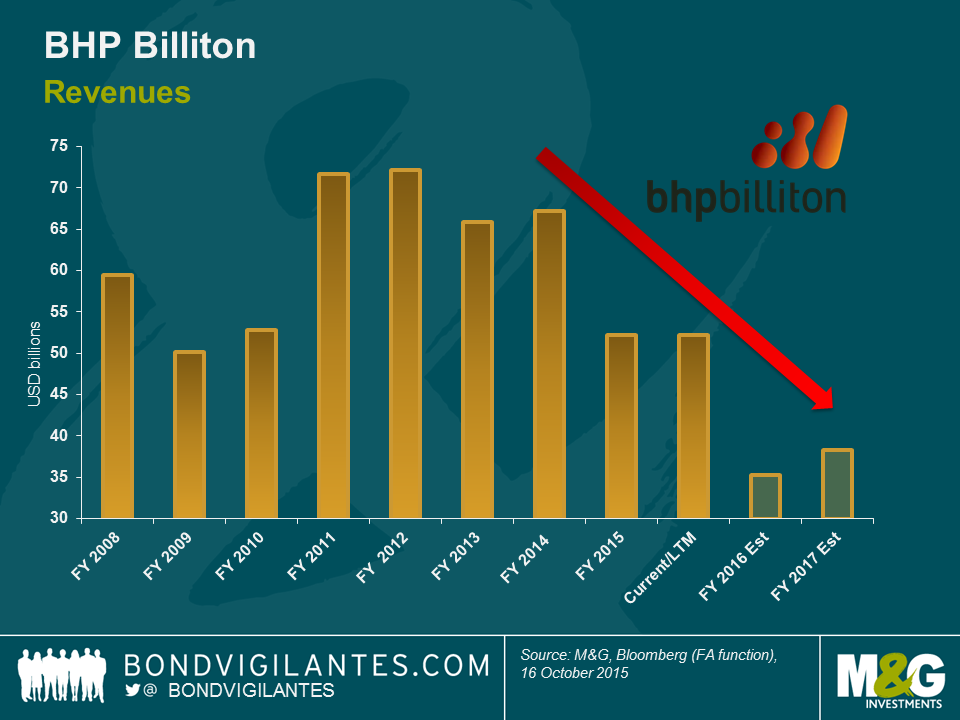

It has been a rough ride for metal and mining giant BHP Billiton. Revenues have come under persistent pressure due to weakening commodity prices. Despite one of the strongest balance sheets in the sector, promises made to shareholders have proven tough to keep.

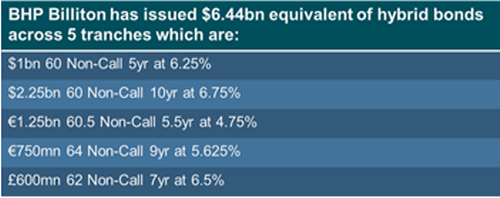

With these commitments in mind the company turned to a nervous bond market earlier this week for some $6.44bn equivalent of hybrid debt funding as outlined below.

Back in May 2015 BHP spun off certain assets into a new business – South32 – whilst assuring investors it would be able to maintain the company’s dividend in line with its policy to ‘steadily increase or at least maintain the dividend per share.’ At current prices and despite a significant cost cutting exercise, the company will be free cash flow negative to the tune of -$2.5bn after maintaining said dividend. With little sign of a near term recovery in commodity prices and a commitment to a solid single A rating, it would seem management have somewhat backed themselves into a corner. A sceptical equity market has watched the implied dividend yield climb significantly through 2014 and 2015 to an elevated 10% area today.

Locking in a blended cost of hybrid debt funding at 6% for a minimum of five years, primarily to maintain the dividend in the face of commodity weakness, may well prove to be a costly error. With an interest bill set to rise by $160m per annum (before tax shield savings), perhaps a near term cut to the dividend would have been a more appropriate response which frankly is already discounted by the market.. Companies often pay special dividends when times are good and turn to bond markets when times are tough. The reason is that reducing the dividend can be a costly exercise for existing equity owners which is a short-sighted strategy in my opinion. Cyclical companies – like BHP – should leave themselves scope to respond to both cyclical downturns as well as upturns. No one can tame the commodities cycle.

As value investors we would generally assert that every financial asset has its price. Few bond market offerings tick all the boxes, but if we are to be suitably compensated, and subject to certain red lines, we are generally sanguine.

Yesterday saw XPO Logistics, a third party US based logistics firm raise $2bn equivalent of debt across Euros and Dollars to part fund its acquisition of Norbert Dentressangle (ND), a French logistics player. Pro forma the acquisition of ND, the company will be a top 10 player globally with revenues of nearly $9bn, will acquire greater scale and a presence in a fragmented European market. The company enjoys multi-year contracts with high renewal rates, limited client concentration, a well-regarded management team with experience of making and integrating acquisitions and a track record of raising equity from sovereign wealth investors. Furthermore, capital expenditure should reduce over the coming years allowing for greater free cash flow generation which could be targeted towards debt reduction. Finally the company has adequate liquidity, an enterprise value of nearly $4bn, a share price that has nearly doubled in the last year, and may well continue to be supported by a multi-year sector consolidation phase.

So what is not to like? Firstly, the business carries a significant amount of debt. On our calculations the current debt load is almost six times EBITDA with the bond indenture allowing for the company to raise further debt, perhaps to fund further acquisitions. Largely though not entirely for this reason the debt is rated B1 by Moodys and B by S&P, essentially half way down the high–yield rating scale.

Secondly, the ‘asset light’ nature of the business is unlikely to result in a high recovery for creditors should the business get itself into difficulty. We would also question the synergies that can be delivered between the existing XPO business and Norbert Dentressangle given the geographic separation and would expect some integration headaches to come. Fourthly, this is an industry with historically low margins and fairly low barriers to entry. Finally, we also took issue with level of protection offered by the bond documentation. Covenants are generally loose which allows the company to incur significant debt that would rank prior to the new bonds (and further impact recoveries), guarantees are only offered from a relatively small part of the business and there is capacity to see dividends paid out to shareholders, even if this is not currently the intention.

Back to the earlier question of value. With a coupon paying 5.75% on the six year Euro notes and 6.5% on the seven year USD notes, and crucially with limited call protection which allows the bonds to be refinanced in the next few years, we ultimately took the view that this financial asset was not suitably compensating us and fell shy of our targeted yield for the name. That said, as a former colleague used to to say, ‘these yields aren’t door numbers.’ There may well come a time when we see a more attractive entry point & having done our credit work we will watch the bonds closely.

Finally at this point I should add that much of the excellent analysis that we are privy to is carried out in the first instance by our team of analysts. In this case I have Miriam Hehir to thank.

Almost two years ago to the day we wrote about a return of animal spirits, the LBO of Heinz by Berkshire Hathaway and 3G, and the significant role debt had to play in the transaction. Yesterday Heinz announced that it is to merge with Kraft Foods to create the fifth largest food and beverage company in the world. The transaction will see Berkshire Hathaway and 3G invest an additional $10bn in the form of a special dividend to Kraft shareholders, in order to take a controlling 51% shareholding in the combined company.

In the Berkshire Hathaway 2014 Annual Report Warren Buffet spells out the acquisition criteria he looks for, most of which is satisfied here. These are that the purchase be large, that the company has demonstrated consistent earning power and good returns on equity whilst employing little or no debt, that it has strong management in place, a simple business, and an offering price (i.e. a business that is readily up for sale). I say ‘most’ as one could readily argue that $8.6bn of current long term liabilities at Kraft (as at the end of the financial year 2014) doesn’t satisfy that ‘little or no debt’ criteria. And Heinz also carries its fair share of debt at $14bn, though both figures need to be taken in context.

In the same Annual Report referenced above Buffett extols the virtues of Berkshire Hathaway and its ability ‘to allocate capital rationally and at minimal cost.’ He goes on to say that Berkshire can ‘ move huge sums from businesses that have limited opportunities for incremental investment to other sectors with greater promise.’ No doubt he and his partner Charlie Munger have an enviable record in doing exactly that, but recently it could be argued the pendulum has been swinging increasingly in their favour.

The mega LBOs that saw the likes of Caesars, TXU, Freescale & Clear Channel acquired pre-Lehman by multiple private equity shops acting in concert are unlikely to be contemplated today. And even if they were, satisfying the requisite 15-20% return on capital would prove challenging on the back of several up years for most equity markets.

Berkshire Hathaway on the other hand has cemented its position as a behemoth that can continue to call on massive cash reserves and an exceptional reputation. And so can it call on super cheap funding from the bond markets. Despite articulating a general distaste for debt its increasing willingness to do so saw the holding company lose its AAA/Aaa status a few years back. And more recently it would seem that the super cheap funding available from bond markets has proven too attractive to ignore. Only this month, Berkshire Hathaway borrowed €3bn from the European credit markets. At a weighted average cost of funding of 1.2% for up to 20 years the company has a huge arbitrage available that can’t be matched elsewhere. Despite the re-rating that has occurred in equity markets, an implied earnings yield of 6-7% still looks attractive if a decent portion of your term funding costs are close to zero.

With central banks continuing to ensure that liquidity remains plentiful Berkshire Hathaway is likely to sit pretty. Meanwhile, the arbitrage opportunities look set to continue. Other large deals will be on the horizon.

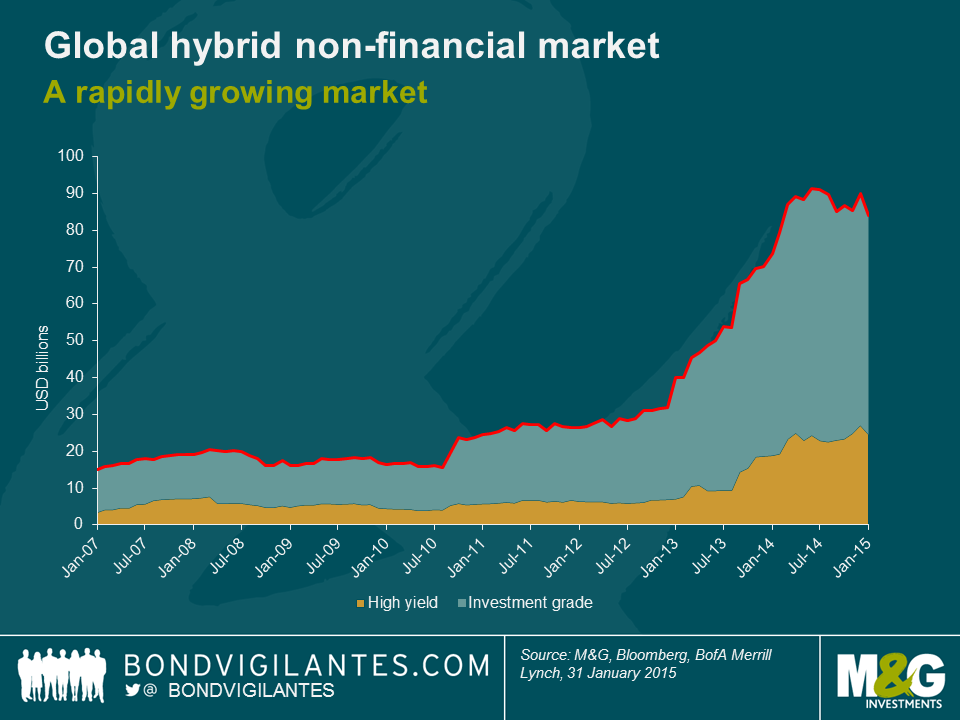

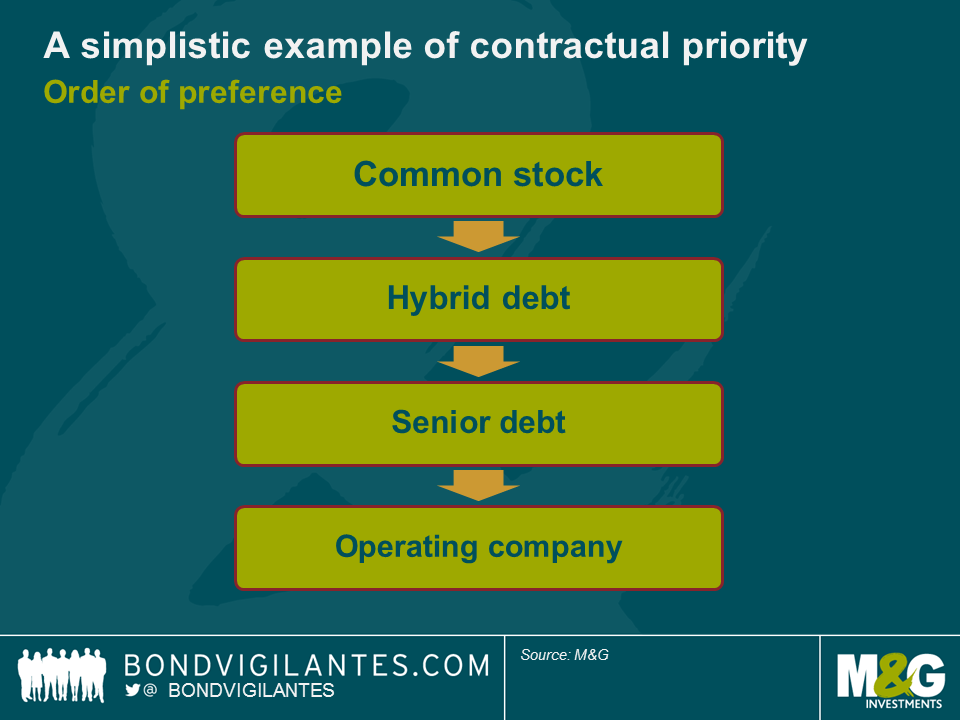

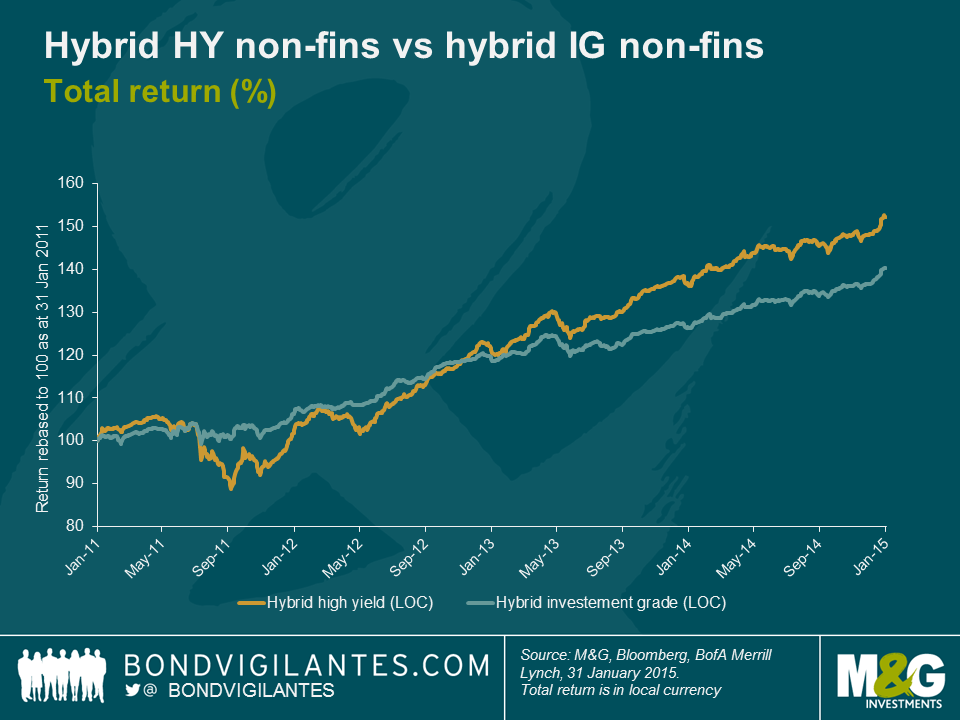

The rapid growth of the hybrid corporate capital market (non-financial) over the last few years has provided fixed income investors with an opportunity to access a quasi-equity income stream. Much like equities, hybrid bonds are perpetual in nature (though an option to call exists), and allow the issuer a degree of discretion over coupon payments. And, whilst they rank ahead of common equity in the event of liquidation, they are contractually subordinate to the more commonly issued senior debt.

As we wrote in 2010, the incentive to issue hybrid capital is clear. The credit rating agencies assume a degree of equity benefit for the hybrid capital that is dependent upon the issuer and structure in question – this enables support for an issuer’s credit rating that would typically otherwise have to come from good old-fashioned equity. Hybrids don’t require existing owners to be diluted nor are any voting rights sacrificed. Furthermore, issuers are also able to treat hybrids as debt for tax purposes, deducting coupons from taxable income.

The economics from an issuer’s perspective may look something like the following. Let’s make a few basic assumptions: a European company can on average issue equity at 7% and senior debt at 1.5%, which translates to 1% after tax. Let’s also assume that the rating agencies allow 50% equity credit for hybrid capital.

So, to achieve a 50/50 equity/debt mix a company treasurer can either issue a hybrid at, say, 3% whose true cost is 2% after tax; or issue a mix of 50% equity at 7% and 50% senior debt at 1% after tax. The blended cost of the latter is 4%, which is approximately 2% more expensive than issuing a hybrid.

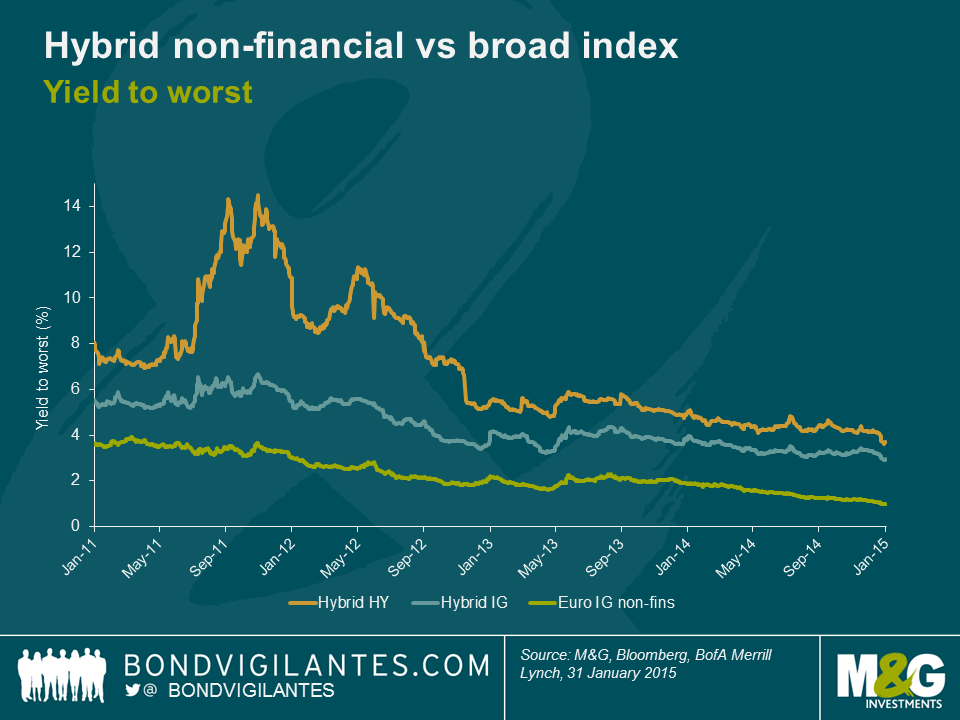

Thus the argument for issuing hybrid capital is a fairly compelling one and is likely to feature for years to come in fixed income markets. However, from an investor’s perspective, the case is perhaps a little more nuanced.

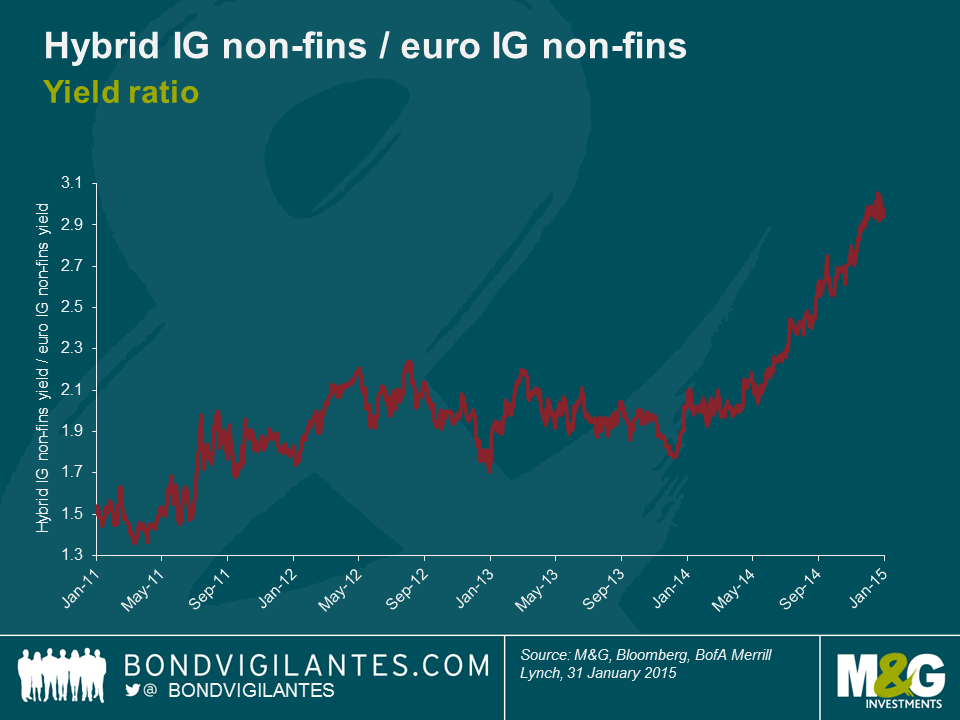

Like all financial market assets the hybrid capital market has been supported by an extremely benign discount rate in recent years. In a world of scarce yield and a desire for exposure to large, multi-national corporates the hybrid market ticks many boxes. In fact, to replicate the average yield available from corporate hybrids with an average rating BBB/BBB- , an investor would need to invest in the senior debt of BB-/B+ rated companies – essentially giving up four notches, not forgetting that hybrid notes are already rated several notches lower than their parent ratings due to the contractual subordination.

Hybrid capital has already been one of the principal beneficiaries of central bank balance sheet expansion in recent years. In January alone, the universe returned 2.73% after the ECB’s QE announcement. And with high-quality industrial corporate bond yields practically at zero, the ratio between hybrid capital and senior debt looks as attractive as ever, though some caution should be applied given that the denominator is so close to zero.

With European investors as keen as ever to own quality yield we can continue to expect both issuers and investors to look upon the market favourably. Whether both sides of the equation will look back on these securities with the same fondness in several years’ time is anyone’s guess.

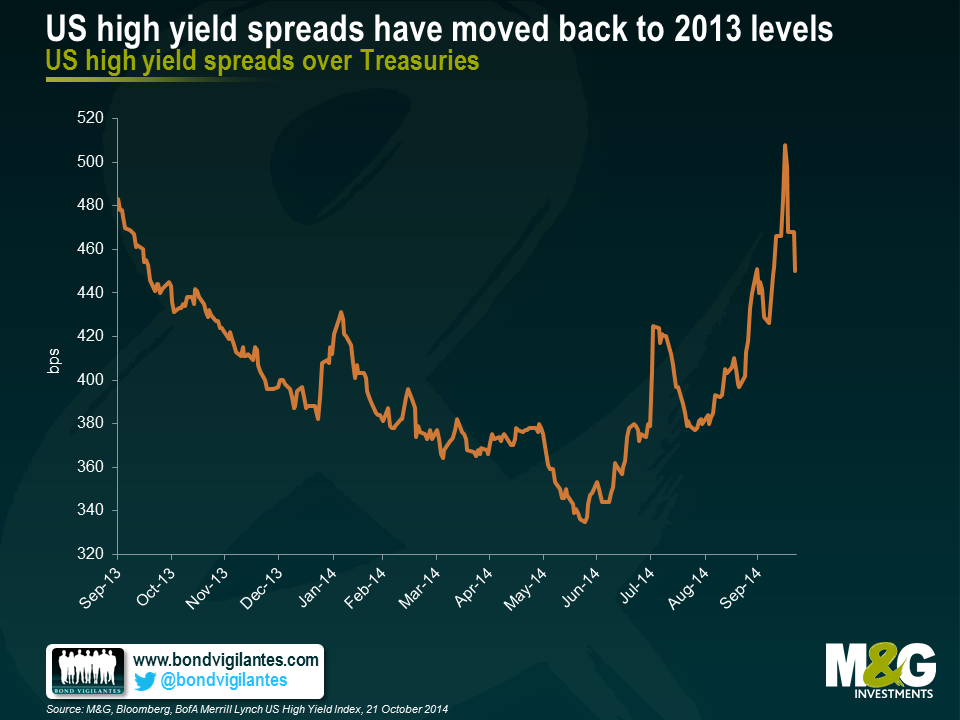

Global growth concerns, fears of a less accommodative Fed, and limited high yield market liquidity coupled with complacent and crowded investor positioning has served to reprice the US high yield market over the past few months. Following on from the worst quarterly performance in Q3 2014 for some three years, the US high yield market arguably now offers a significantly more attractive entry point. Whilst acknowledging that the market has moved faster over the past few days than I was able to write this blog, here are ten reasons why US high yield could be considered a buy at these levels:

- Spreads have moved back to levels not witnessed since October 2013. In June this year, spreads had only been tighter for around 17% of the time (since our data began in the mid-1990s). The recent correction left this number peaking at around 40%.

- The yield on the BofA Merrill Lynch US High Yield Index recently reached 6.4%, having traded as low as 4.85% in June, and is currently around 6%, a level likely to appeal to institutional buyers.

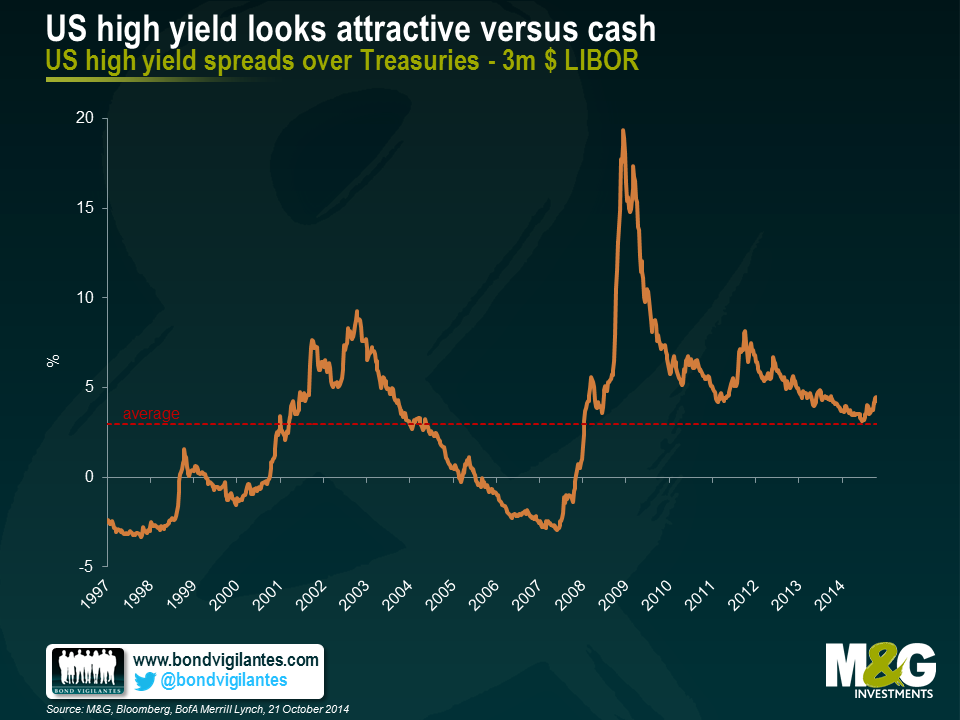

- Whilst the absolute level of yields may look low by historic standards, valuations relative to cash and government bonds still look compelling.

- Given the relatively high level of income the asset class generates, and a benign outlook for defaults, the asset class can suffer considerable spread widening before underperforming cash and government bonds. Assuming a 2% default rate and no change in government bond yields, high yield spreads would need to widen by approximately 100bps from current levels to underperform a similar duration US Treasury bond. This would see spreads back at levels not witnessed since 2012.

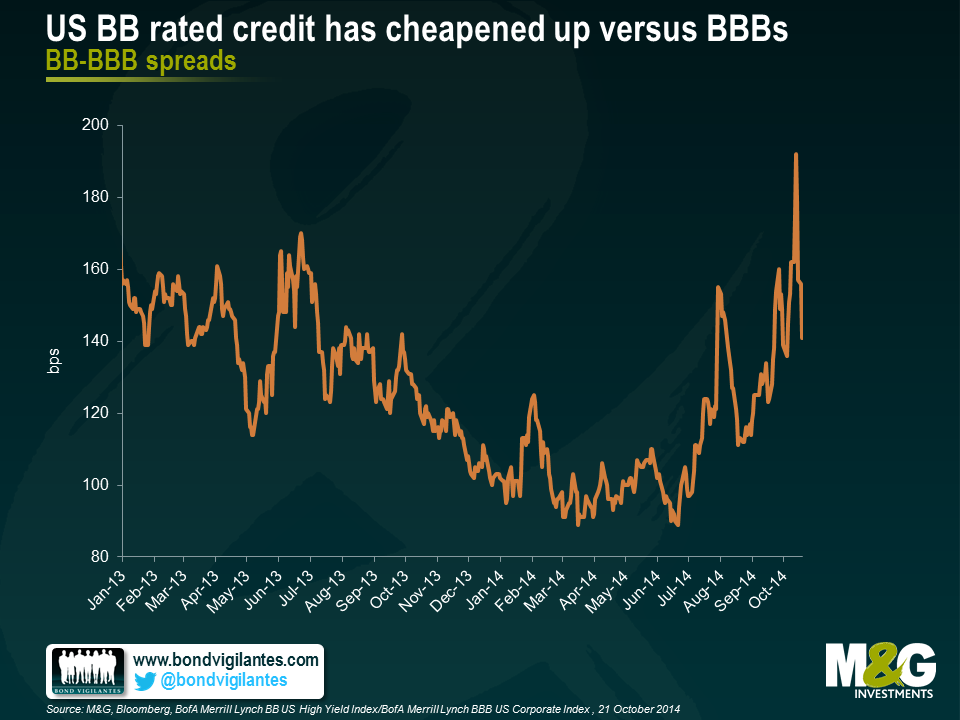

- Other fixed income assets have significantly outperformed high yield so far this year. According to BofA Merrill Lynch indices, US Treasuries have returned 5.5% and investment grade corporates have returned 7.7% year-to-date, while US high yield has gained 4.5%. As the chart below shows, BB rated bonds (the highest rated category of the high yield market) have cheapened up considerably vs BBB corporates.

- Technicals are in a much better place than they were a few months ago, with the asset class having witnessed some $21 billion of outflows in 2014 (according to BofA Merrill Lynch). New issue supply has slowly abated and the market is becoming more discerning about taking risk.

- US high yield company fundamentals, although having worsened slightly over the past couple of years, still look in reasonable shape, with leverage and interest cover both at 3.9x at an index level.

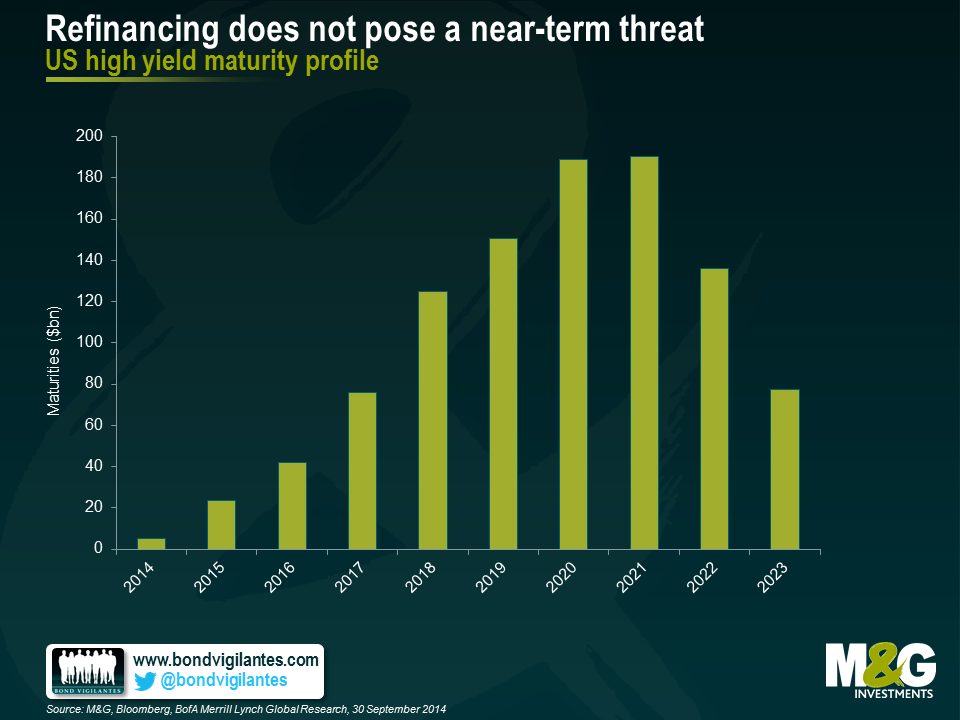

- The backdrop for defaults remains benign. Re-financing risk is one of the major obstacles for leveraged companies, but this risk appears limited over the next couple of years as many companies have taken advantage of abundant liquidity to term out their debt, as illustrated in the chart below.

- When the Fed eventually raises rates, it is likely to err on the side of caution and tighten policy slowly. The carry trade is unlikely to come to an abrupt end in the near future.

- Tighter policy is likely to be accompanied by an improving economic backdrop. Whilst the corporate profit share of GDP is already relatively high, it is likely that this would be sustainable in a stronger economy.

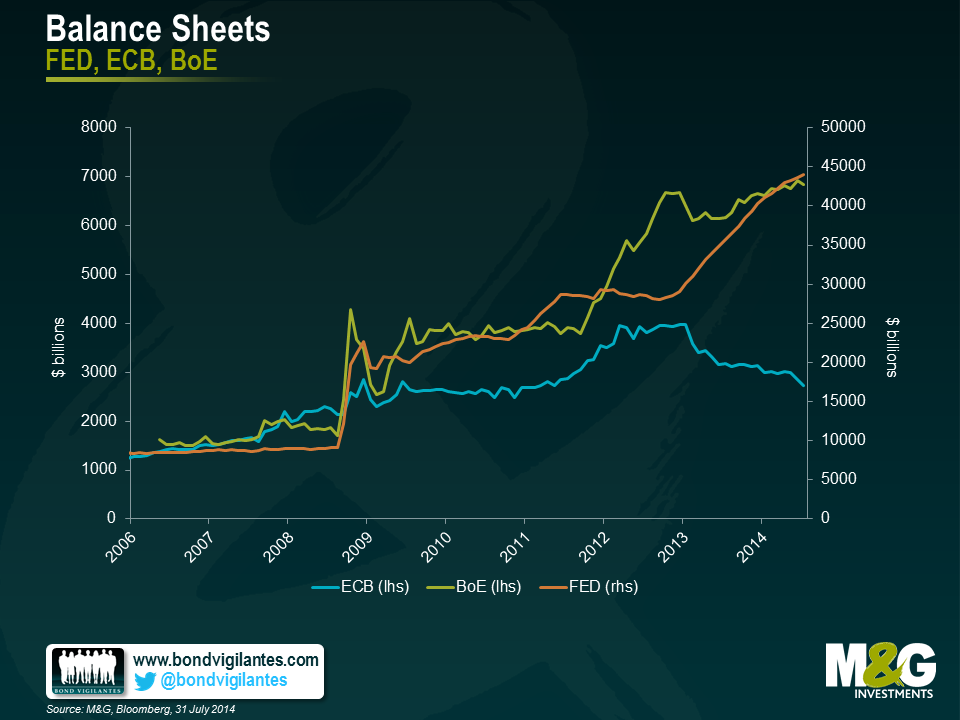

Richard recently wrote about the exceptional times in bond markets. Despite bond yields at multi-century lows and central banks across the developed world undertaking massive balance sheet expansions the global recovery remains uneven.

Whilst the macro data in the US and UK continues to point to a decent if unspectacular recovery, the same cannot be said for the Eurozone. Indeed finding data to be overly optimistic about is no easy task. Both consumer and business confidence indicators continue to point to a subdued recovery; parts of Europe are technically back in recession and inflation readings continues to disappoint to the downside. The most recent CPI reading came in at a mere 0.4%, German breakevens currently price five year inflation at 0.6% and longer term expectations have shown signs of questioning the ECB’s ability to deliver on the inflation mandate.

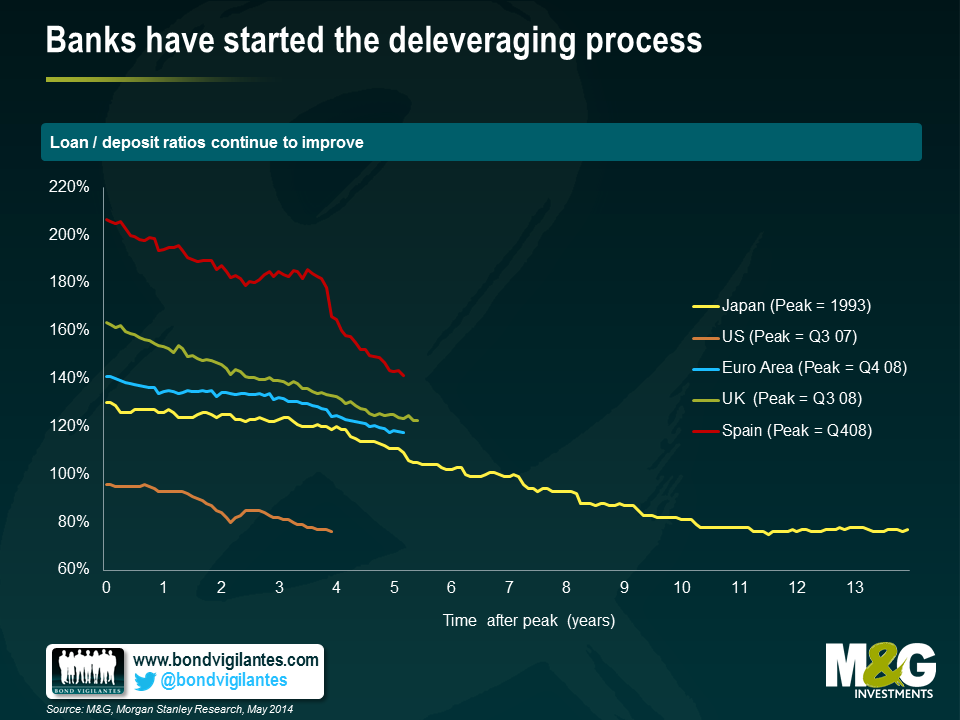

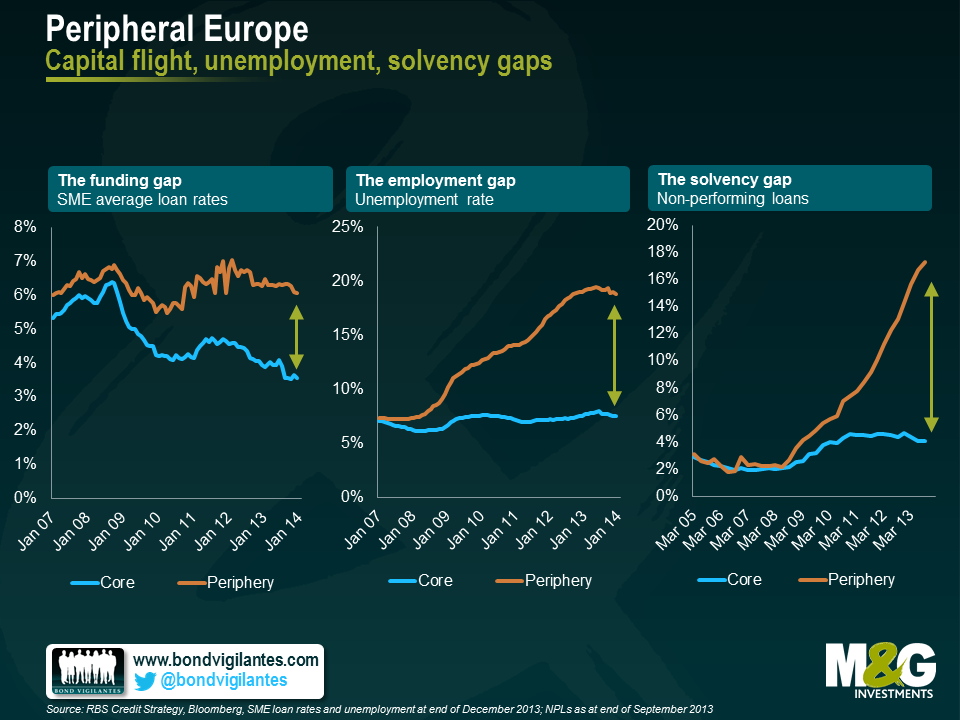

Recognising the sheer size of the Eurozone banking system remains key to understanding the challenge Eurozone policymakers face. With a banking system over three times larger than the US (relative to GDP); significantly higher non-performing loans and massive pressure to deleverage as shown in the first chart below, it is unsurprising that the so called transmission mechanism appears damaged. The failure to pump credit into the Eurozone economy, especially into the periphery, continues to weigh on funding costs for SMEs & promote exceptionally high levels of unemployment. These are only now beginning to stabilise at elevated levels as shown in the second chart below.

With previous demands for austerity in Europe preventing economies from running counter-cyclical fiscal policies and uneven progress in structural reform, the onus continues to fall on monetary policy and the ECB. And yet for a variety of reasons the response has fallen considerably short of that from the FED, BoE & BoJ, who have been happy to expand their balance sheets considerably.

The result has been, an overvalued Euro, imported disinflation and a lack of investment. Having offered re-financing cuts, forward guidance, massive liquidity in the form of the LTRO & TLTRO, the ECB will ultimately be forced to follow other central banks in undertaking broad asset purchases.

Whilst these broad asset purchases or QE are unlikely to be unveiled today, they are the only likely means in the near term, of ensuring that the banking system in Europe is able to extend significantly more credit to the real economy. This in turn should help to raise inflation expectations, boost potential growth and allow the ECB to fulfil its mandate.

In Europe exceptional times call for exceptional measures. The ECB isn’t done, even if certain members will have to be dragged kicking and screaming to the QE party. I expect European bond yields to stay low for quite some time.

Seven years since the start of the financial crisis and it’s ever harder to dismiss the notion that Europe is turning Japanese.

Now this is far from a new comparison, and the suggestions made by many since 2008 that the developed world was on course to repeat Japan’s experience now appear wide of the mark (we’ve discussed our own view of the topic previously here and here). The substantial pick-up in growth in many developed economies, notably the US and UK, instead indicates that many are escaping their liquidity traps and finding their own paths, rather than blindly following Japan’s road to oblivion. Super-expansionary policy measures, it can be argued, have largely been successful.

Not so, though, in Europe, where Japan’s lesson doesn’t yet seem to have been taken on board. And here, the bond market is certainly taking the notion seriously. 10 year bund yields have collapsed from just shy of 2% at the turn of the year and the inflation market is pricing in a mere 1.4% inflation for the next 10 years; significantly below the ECB’s quantitative definition of price stability.

So just how reasonable is the comparison with Japan and what could fixed income investors expect if history repeats itself?

The prelude to the recent European experience wasn’t all that different to that of Japan in the late 1980s. Overly loose financial conditions resulted in a property boom, elevated stock markets and the usual fall from grace that typically follows. As is the case today in Europe, Japan was left with an over-sized and weakened banking system, and an over-indebted and aging population. Both Japan and Europe were either unable or unwilling to run countercyclical policies and found that the monetary transmission mechanism became impaired. Both also laboured under periods of strong currency appreciation – though the Japanese experience was the more extreme – and the constant reality of household and banking sector deleveraging. The failure to deal swiftly and decisively with its banking sector woes – unlike the example of the US – continues to limit lending to the wider Eurozone economy, much as was the case in Japan during the 1990s and beyond. And despite the fact that Japanese demographics may look much worse than Europe’s do today, back in the 1990s they were far more comparable to those in Europe currently.

Probably the most glaring difference in the two experiences is centred around the labour market response. Whereas Eurozone unemployment has risen substantially post crisis, the Japanese experience involved greater downward pressure on wages with relatively fewer job losses and a more significant downward impact on prices.

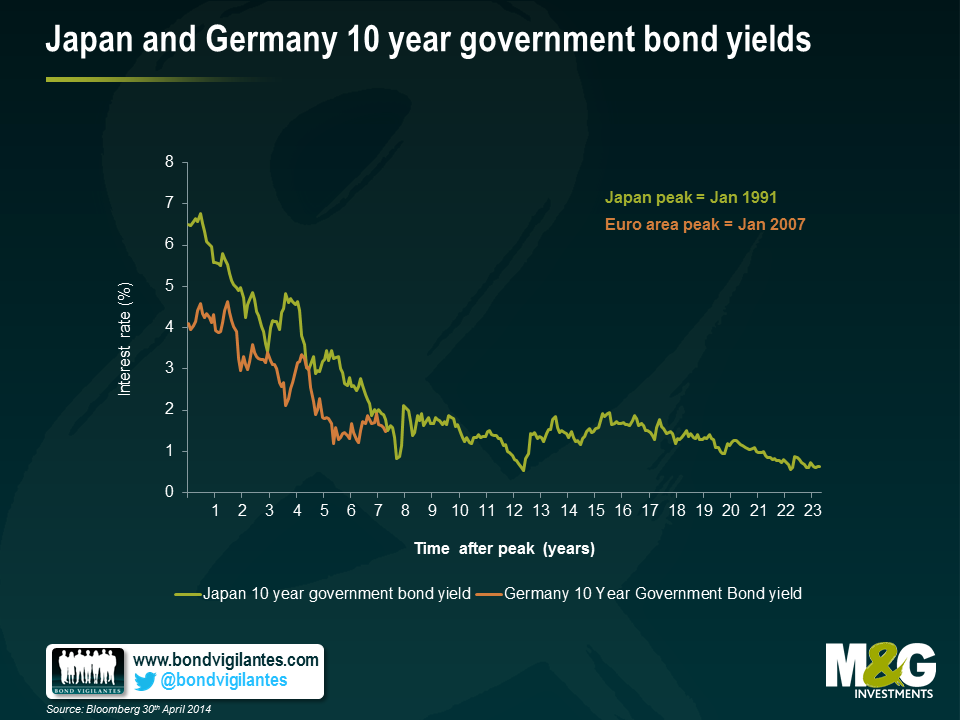

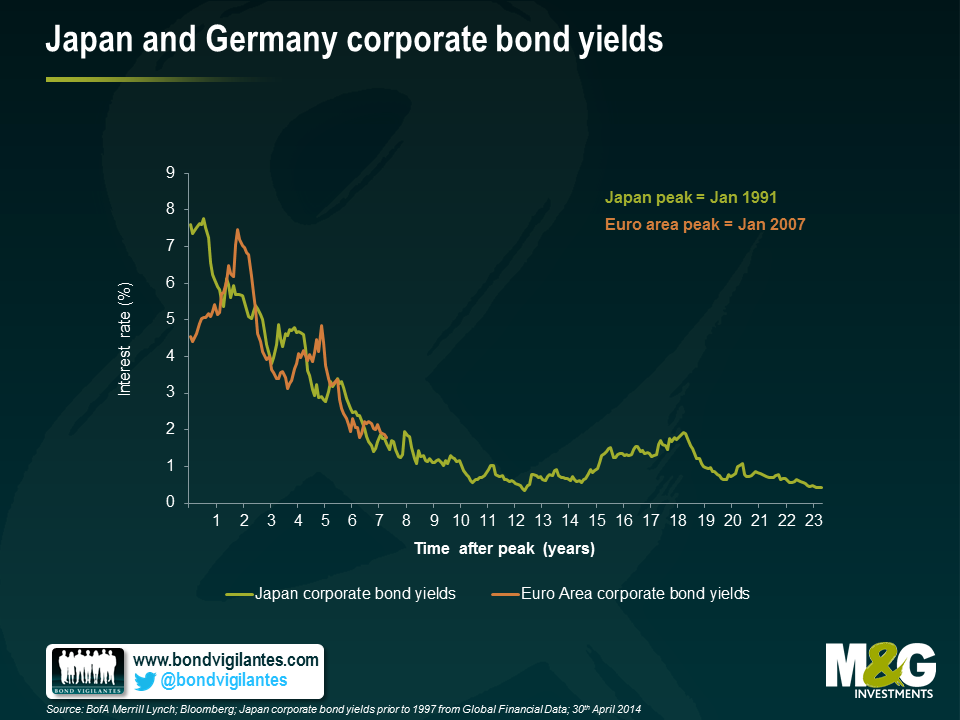

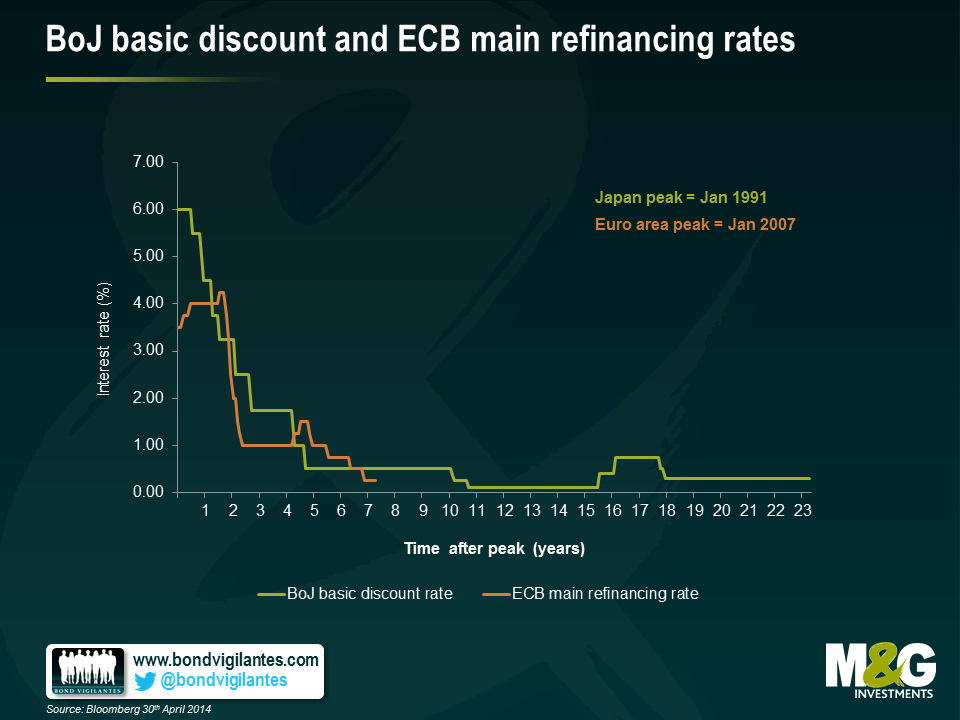

With such obvious similarities between the two positions, and whilst acknowledging some notable differences, it’s surely worthwhile looking at the Japanese bond market response.

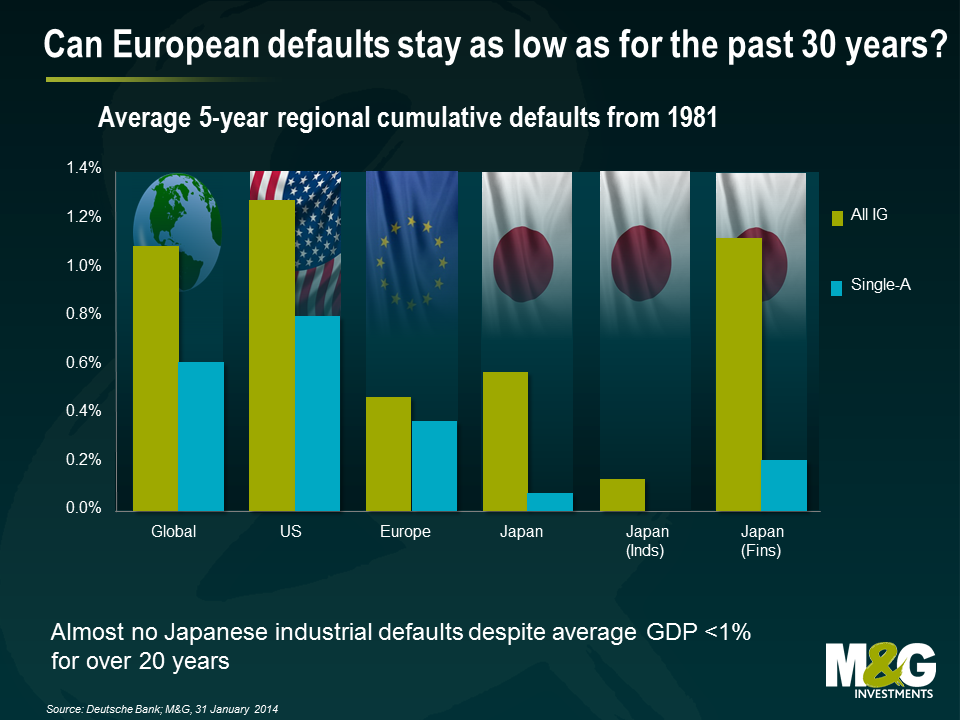

As you would expect from an economy mired in deflation, Japan’s experience over two decades has been characterised by extremely low bond yields (chart 1). Low government bond yields likely encouraged investors to chase yield and invest in corporate bonds, pushing spreads down (chart 2) and creating a virtuous circle that ensured low default rates and low bond yields – a situation that remains true some 23 years later.

As an aside, Japanese default rates have remained exceptionally low, despite the country’s two decades of stagnation. Low interest rates, high levels of liquidity, and the refusal to allow any issuers to default or restructure created a country overrun by zombie banks and companies. This has resulted in lower productivity and so lower long-term growth potential – far from ideal, but not a bad thing in the short-to-medium term for a corporate bond investor. With this in mind, European credit spreads approaching historically tight levels, as seen today, can be easily justified.

Europe currently finds itself in a similar position to that of Japan several years into its crisis. Outright deflation may seem some way off, although the risk of inflation expectations becoming unanchored clearly exists and has been much alluded to of late. Japan’s biggest mistake was likely the relative lack of action on the part of the BOJ. It will be interesting to see what, if any response, the ECB sees as appropriate on June 5th and in subsequent months.

Though it is probably too early to call for the ‘Japanification’ of Europe, a long-term policy of ECB supported liquidity, low bond yields and tight spreads doesn’t seem too farfetched. The ECB have said they are ready to act. They should be. The warning signs are there for all to see.