Guest contributor – Tolani Benson (Financials/Sovereign analyst, M&G Credit Analysis team)

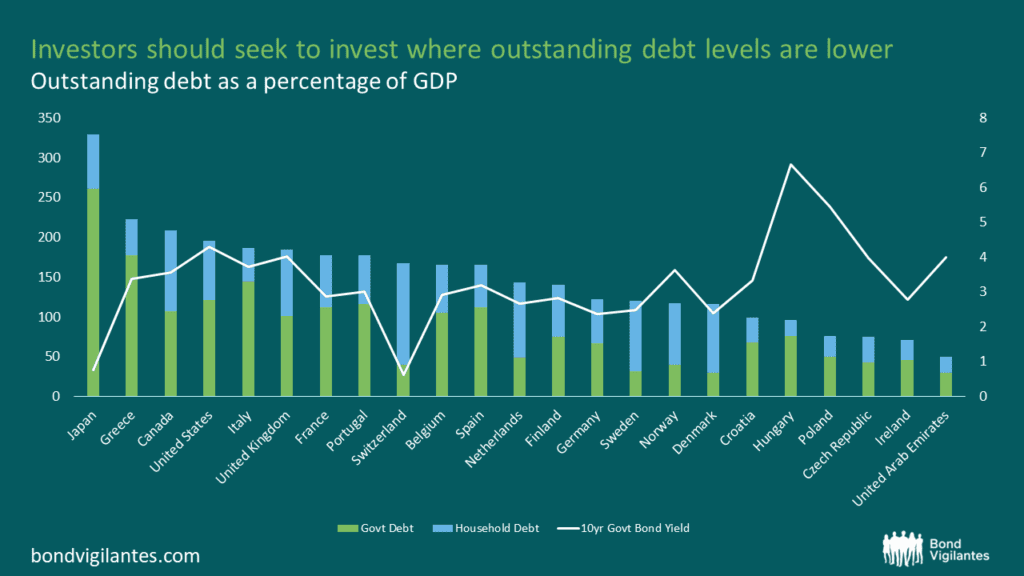

Hungary has a substantial amount of debt outstanding – the IMF estimates levels were around €75bn at the end of last year, corresponding to 74% of GDP. Its local currency debt makes up a decent proportion of emerging market indices, constituting a not insignificant 4.6% of the widely used JPMorgan GBI-EM Global Diversified Index. A drop in Hungarian government bond values and/or the Hungarian forint means a drop in the index.

Not an EM investor? A substantial proportion of Hungarian sovereign debt is also owned by its banks, which are themselves owned by the Western European banks you may be more familiar with. Hungarian government bond holdings at three of Hungary’s biggest foreign owned banks were equal to between 10% and 25% of their parent banks’ tangible common equity at YE 2011 (2012 data isn’t out yet for the Hungarian banks). These three large parent banks have all had to receive bail-out capital from their respective governments since 2008 – a writedown of their Hungarian government bonds would not be a minor event for any of them. Appetite for recapitalising banks in the Eurozone is moving increasingly away from government capital injections towards bailing in unsecured senior and subordinated creditors and uninsured depositors, as we have seen with this week’s debacle in Cyprus.

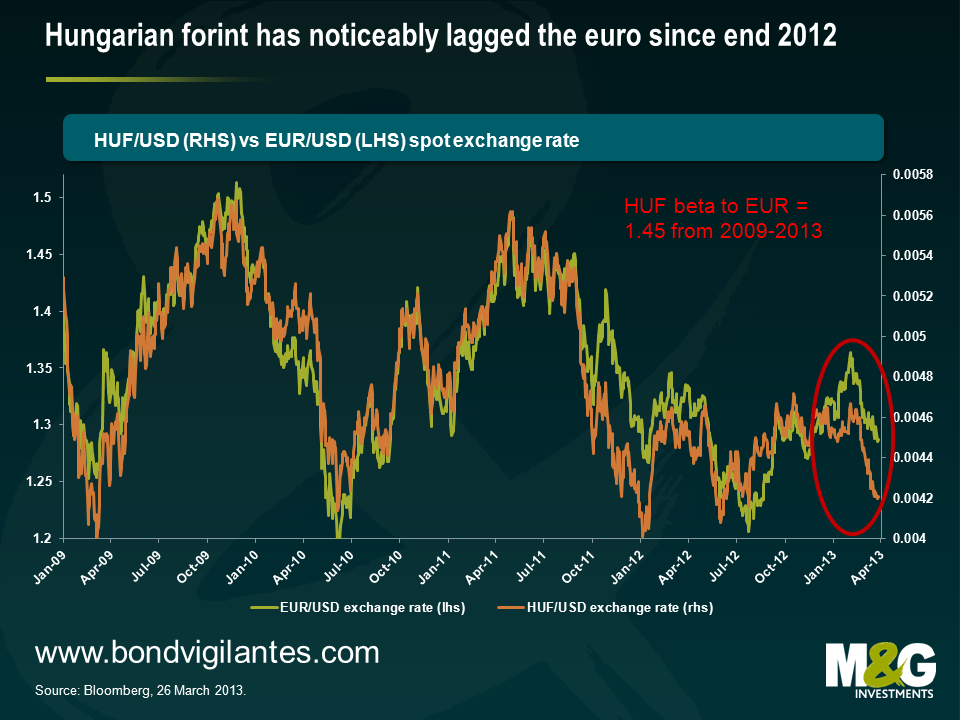

So what is going on in Hungary? Hungary’s currency, the forint, has always been a high beta version of the euro (see chart), but it has significantly underperformed since mid-October, plummeting 10% against the euro. And on Friday we saw the forint reaching a 52-week low after S&P changed their outlook on Hungary to negative (currently rated BB by the agency).

Some may argue that for a highly indebted nation suffering from a stagnant economy, a devaluing currency should be a good thing – Hungary becomes more competitive, economic activity picks up, government revenues increase, the deficit decreases, and government debt levels fall – great.

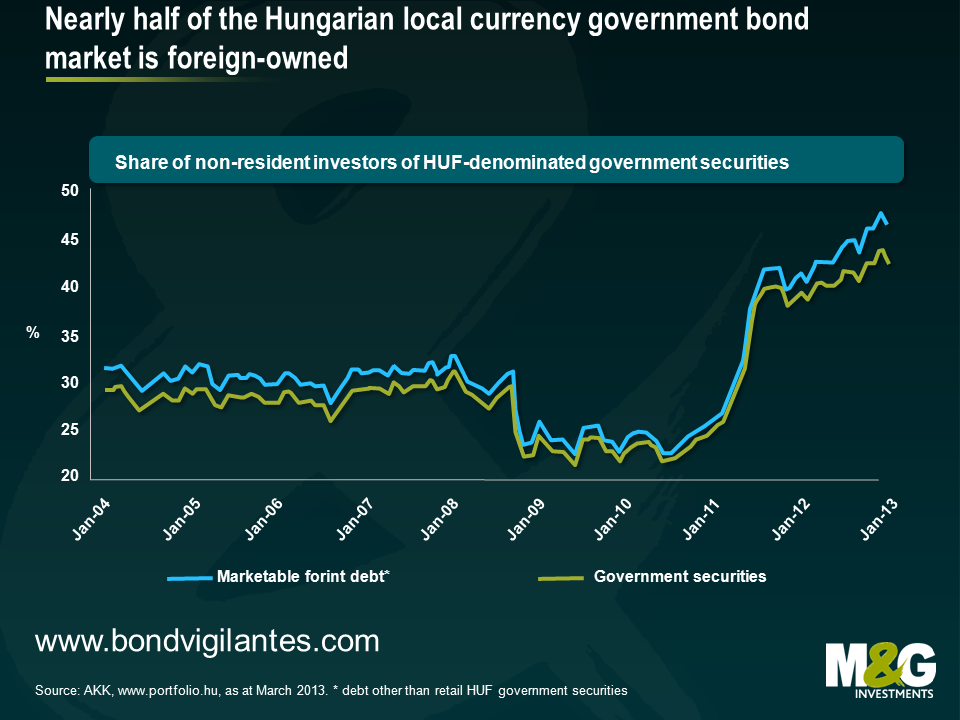

If only things were that simple. Forint weakness is a serious problem for Hungary. It has huge amounts of foreign currency debt across the whole economy; the government, its citizens, and corporations. The weaker the forint becomes the more expensive it is for both the public and private sectors to service their debts. Plus, almost half of the government’s local currency debt is held externally (see chart), making it extremely vulnerable to sell-offs in the forint. If foreign investors pull out, Hungary’s funding costs will soar and the country will struggle to refinance. The ECB puts the Hungarian economy’s gross external debt (i.e. any liabilities held by foreign creditors, including foreign owned domestic debt) at almost 130% GDP. Economists Reinhart and Rogoff in their paper ‘Growth in a time of debt’ have estimated that growth is significantly impaired when external debt is beyond 60% of GDP, and growth rates are halved above 90% of GDP. In their 2003 study with Miguel Stevanso, ‘Debt intolerance’, they also found that when external debt to GNP ratios are above 30-35% in emerging market economies, there is a substantial increase in the likelihood of a credit event. Hungary is well beyond these threshold levels, which should set alarm bells ringing.

Though the weak forint has helped Hungary’s trade balance, it is not enough. Despite posting a trade surplus of €6.8bn in 2012, GDP contracted by 1.5%. Unemployment is high and rising, reaching 11.2% in January this year. Hungarian businesses have been stifled by the credit crunch that has come about as a result of the government’s measures to reduce its citizens’ foreign currency debt burdens by writing off huge amounts of individuals’ debts, forcing losses onto the banks and restricting their ability to lend. And herein lies the root of most of Hungary’s problems; government policy.

Since taking power in 2010, the current government has been chugging out reams of controversial and counter-productive policies whilst making countless changes to the constitution. Such behaviour has been making investors uncomfortable, causing the forint to devalue. The business environment in Hungary is far too volatile to attract external investment – the key to growth – due to constantly changing regulation, heavy industry levies, and the possibility that the government may nationalise private corporations. Economic policy has been questionable, relying more upon one-offs such as the highly contentious appropriation of citizens’ private pension fund assets onto the government balance sheet, and much less upon vital structural change. Attitude towards the IMF since requesting a bailout loan in 2011 has been confrontational, with various government departments dismissing any need for assistance. The government started publishing anti-IMF propaganda in local media portraying the IMF as a threat to the country’s sovereignty. Unsurprisingly, any IMF deal now seems to be off the table.

Even more troubling than the government’s handling of the economy are the changes it has implemented at key institutions. It has thrown out the independence of the central bank by taking control of appointments, dismissing independent members, and placing the government’s former Economy Minister in the top seat as Governor, and in the process replacing the hawkish former governor, András Simor, who consistently resisted government attempts to influence monetary policy. The most concerning change is doing away with the Constitutional Court’s ability to perform its intrinsic function. Its power to overrule legislation that is deemed unconstitutional has been removed, so that it may only object on procedural grounds. This also allows any previous rulings by the Constitutional Court to be thrown out, effectively allowing the government to undo work done by the court to protect Hungary’s citizens in the past.

Being a member of the EU, Hungary’s actions have not gone unnoticed, but as yet appear to be unpunished. Hungary is like the naughty student that gets called up to the headmaster’s office every day – only the headmaster is the EC, and rather than silly classroom pranks, this bad behaviour is much more concerning. Should the forint continue its gradual demise it is the Hungarian citizens that suffer with a stagnating economy, a credit crunch, and the gradual withdrawal of their human rights. They will also have to deal with the long period of painful austerity that is inevitable when the IMF eventually has to pick up the pieces after years of terrible policy decisions have run the country into the ground. If that IMF assistance involves restructuring of sovereign debt, it is also the holders of EM debt and creditors of some large Western European banks that may be feeling the pain.