Jim Leaviss’ Panoramic Outlook

A view of the year ahead in the bond markets

With many expecting a ‘great rotation’ out of fixed interest assets in 2013, bond investors will, in the main, have experienced a better year than some had predicted 12 months ago. It might not always have felt like it at the time – indeed, over the summer when markets were sent into a spin by the prospect of the US Federal Reserve (the Fed) cutting its supply of liquidity earlier than expected, it almost certainly did not. But riskier assets, notably high yield corporate bonds, have continued to perform strongly, while investment grade corporate bonds are on track to deliver another year of positive returns, in spite of the volatility.

Meanwhile, the macroeconomic backdrop has generally improved over the past year, with the economic recovery gaining significant momentum in the US and, more recently, the UK. However, the picture in Europe remains mixed, while our concerns over the emerging markets are mounting. However, despite their disparate prospects, all countries – and all bond markets – are united by at least one common dependency: the Fed.

The great taper debate

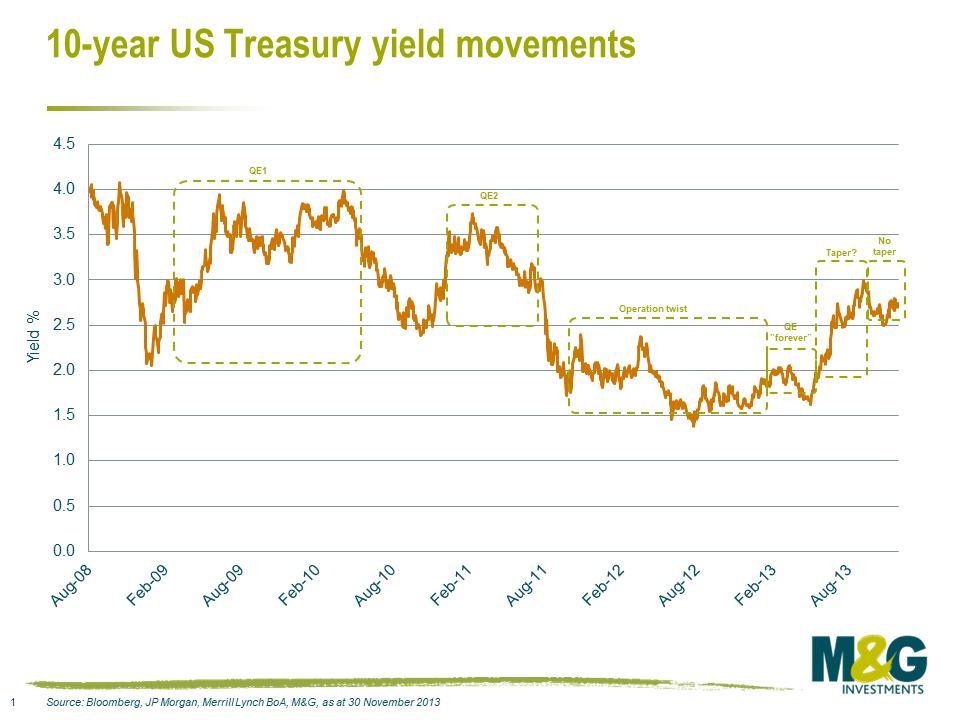

While investors might have started 2013 unfamiliar with the concept of ‘tapering’, the same is certainly not the case going into 2014. Since its introduction into the financial lexicon in May, markets have been in thrall to the ‘will-they-won’t-they’ nature of the great taper debate. As chart 1 shows, every new data release has only served to increase speculation and financial markets’ favourite soap opera is delicately poised as we enter 2014.

Although the exact timing of the taper is uncertain, one thing is clear. In our outlook for 2013, we set out our positive view of US growth prospects, driven by encouraging developments in the country’s housing market. One year on, and the reasons that led us to be optimistic about US economic growth – including an improving current account balance and steadily falling unemployment rate, as well as the rebounding housing market – remain in place.

Janet Yellen

Currently the Federal Reserve’s Vice Chair, Janet Yellen is the US labour market economist on course to become the world’s most important central banker. She has a reputation for ‘dovishness’ – a greater focus on unemployment than inflation – something we do not expect to change significantly.

Yellen has been a vehement advocate of accommodative monetary policy, although she concedes that QE cannot continue indefinitely. Given her background, we expect specific labour indicators to be central to her decision-making process.

It will be interesting to see the framework that a Yellen-led Fed will adopt to determine policy during her five-year term as Fed Chair. Specifically, Yellen has espoused ‘optimal control’ techniques in many of her major speeches. Under this approach, the central bank would use a model to calculate the optimal path of short-term interest rates in order to achieve its dual objective of price stability (2% inflation) and full employment (an unemployment rate of 6%). In a November 2012 speech, Yellen showed that monetary policy as determined by ‘optimal policy’ suggested a Fed Funds rate close to zero until 2016. The optimal control strategy suggests that the Fed would take a more aggressive stance towards fighting above-target unemployment, implying lower short-term rates for longer.

Judging by some of her recent speeches, we would not expect monetary policy accommodation to be fully removed until there is notable momentum in the following:

- Pace of payroll employment growth

- Gross job flows

- Spending and growth in the economy

We therefore expect Yellen to continue with the Fed’s policy of ultra-easy monetary policy. However, while it is easy to label central bankers as ‘hawks’ or ‘doves’, we think this masks the fact that the true driver of monetary policy is data. If we see solid signs of growth momentum, we would not discount the possibility that a Yellen-led Fed will taper sooner than the consensus expects to prove her inflation-fighting credibility.

We are bullish on the US dollar in 2014. Having previously favoured the dollar against emerging market currencies and commodity currencies, after its weakness in the third quarter of 2013, we like it against all other major currencies too. The other long-term positive forces that have driven our excitement (and an increasing number of others) over the dollar, such as compelling valuations following a decade-long slump and the rapid move towards energy independence, will be equally valid in 2014 too. In a world where the UK is running a large current account deficit, Europe is considering sub-zero deposit rates and Japan is following through on a policy to weaken the yen, the US dollar faces the fewest technical and fundamental headwinds.

With the stage now set for the main event in 2014, current consensus has March as a likely contender for tapering to begin. However, there are various considerations that might come into play. One such is growth data: estimates for the drag that the recent US government shutdown will have had on fourth-quarter gross domestic product (GDP) numbers are wide-ranging, and the Fed will want to see that the economy remains on track before withdrawing some of its support. Plus, with only a short-term solution to the debt ceiling question found in October, the US must go through the same rigmarole again in the new year.

In the labour market, meanwhile, it is estimated that payroll growth of 175,000-200,000 per month is sufficient to put significant downward pressure on the unemployment rate, especially if the participation rate remains at its current very low level. We are not expecting a strong increase in the participation rate, due to demographic trends. The country’s aging population is putting the brakes on the participation rate rising, as the participation rate for older workers is lower and many are approaching retirement.

Even if tapering does begin in March, we must not forget that it means purely a reduction in, and not an end to, stimulus. The Fed wants to make it absolutely clear both to those in the real economy and financial market participants that interest rate rises themselves are likely to be much further off.

As we have seen in recent months from the reaction of bond yields around the world to taper speculation, no country is immune from the Fed’s decisions. We would, however, caution against expecting a large bear market for government bonds. Inflation is currently benign and central banks globally will be very gradual in any moves to remove monetary stimulus. Interest rate hikes are still likely to be years away, limiting the potential for a big bear market in bonds.

Even so, volatility in US Treasury markets and a rising US dollar could have a big impact on emerging market bonds. We have been cautious on the asset class for a couple of years. To summarise: we are concerned that the bubble that has developed in emerging markets, driven by surging portfolio inflows, is under threat due to historically tight valuations and the better prospects for the dollar. Equally, we are watching what we see as deteriorating emerging market fundamentals with concern. All of this, in our view, is leading to the possible creation of a perfect storm for the asset class, whereby any move by the Fed to start tapering could lead to huge outflows, the very real risk of currency and/or banking crises, and widespread contagion.

Inflation: a vanishing phenomenon?

One topic has been baffling central bankers, bond investors and economists since the financial crisis: inflation, or the lack thereof. According to conventional wisdom, inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon, therefore causing fear that the extraordinary monetary policy of recent years would trigger rampant inflation across the US, Europe and the UK. We heard how governments and central banks were devaluing their currencies in order to become more competitive. The only way out of the western world’s debt problems would be through a mix of financial repression and a healthy dose of inflation.

More than five years have passed since the global economy was plunged into crisis. Developed world inflation appears remarkably under control, despite record levels of stimulus and money printing. While we have seen ‘sticky’ inflation numbers in the UK, partly due to regulated price increases for utilities, inflation in the US and Europe is well below central bank targets. Arguably, the harsh fiscal austerity implemented by many governments has contributed to the decline in inflation. In fact, central bankers’ current concerns centre on inflation being too low – something that is likely to remain the case in 2014.

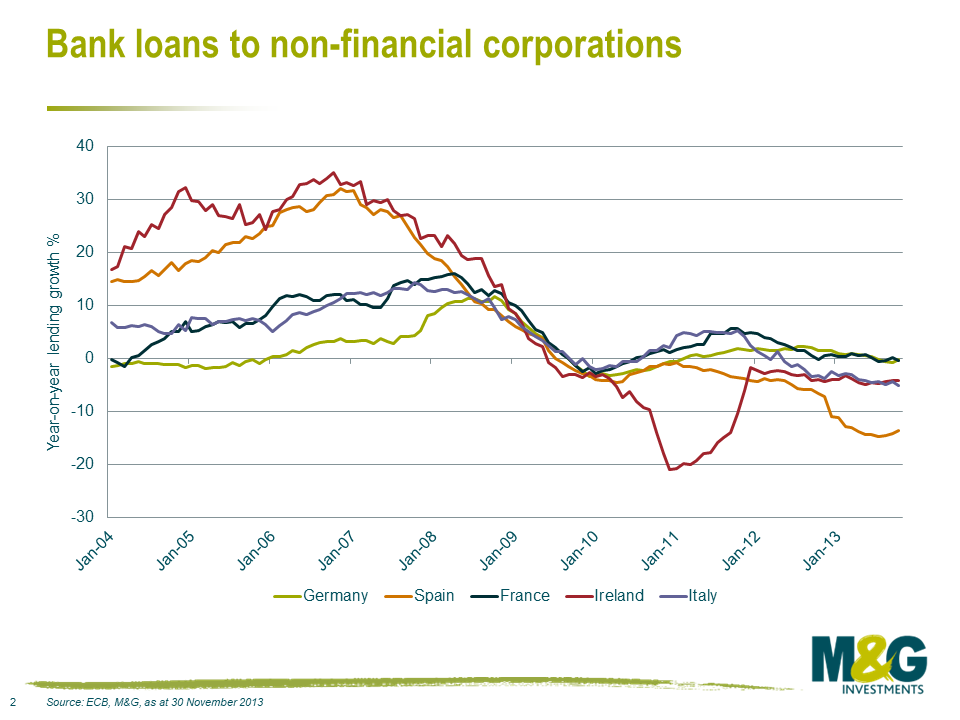

We see one simple explanation why the massive increase in money supply has not fed through to higher inflation: it has not entered the real economy. Commercial banks are flush with cash but are not making many new loans (as chart 2 shows). Fortunately, it appears that banks may now be starting to relax their lending standards, although it is still hard to find creditworthy borrowers, particularly in countries such as Spain, Greece, Cyprus and Ireland. The recovery in lending will be a slow process. Worryingly for central bankers, those countries with negative or weak loan growth also appear most susceptible to deflation.

If we do start to see a pick-up in loan growth, this will likely indicate a strengthening in the quality of economic growth and improved prospects for business and consumer confidence. However, bond investors should not take such developments as a signal for complacency. Central bankers’ greatest fear is that banks’ reserves could flood into the economy, resulting in higher prices and unanchored inflation expectations. It is at times like these that investors must be at their most vigilant.

In 2013, we launched the M&G YouGov Inflation Expectations Survey, a quarterly survey gauging the public’s perception of inflation trends across the UK, Europe and Asia. Whilst inflation has been described as “the dog that didn’t bark” by the International Monetary Fund, we seriously doubt that the dog has been muzzled indefinitely. And, increasingly, the evolution of monetary policy away from inflation targeting towards forward guidance means that both policymakers and markets are monitoring inflation expectations. The first sign that inflation is becoming a problem will show itself through inflation expectation surveys such as ours, which makes vigilance imperative. The report is available at http://www.mandg.co.uk/inflationsurvey.

Should inflation re-emerge, central bankers will face a huge policy dilemma. At M&G, we have frequently mooted ‘central bank regime change’ – this shift away from targeting inflation towards boosting economic growth (and which therefore assists in eroding large debt burdens) – as a reason to own assets such as inflation-linked corporate bonds and floating rate notes. The risks of a monetary policy error have never been greater.

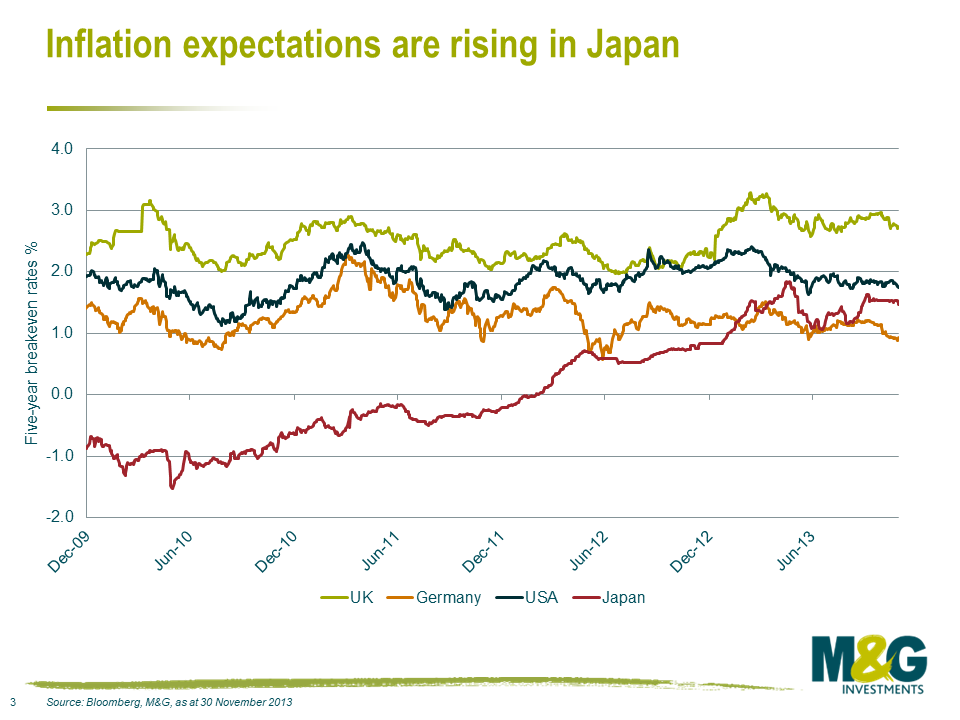

The answer to reflating an economy may lie in Japan, where the ‘three arrows’ of Abenomics – aggressive monetary easing, flexible fiscal policy and structural reforms – are a great experiment in modern economics. The three arrows are the best chance yet that Japan has had to escape from deflation. The theory is simple: aggressive easing, flexible fiscal policy and a strategy of higher inflation will lower real interest rates and result in increased consumption, greater investment and improved export competitiveness through the weaker yen.

We see encouraging signs that Abe’s policies are working. The yen has fallen by 15.3% in 2013 against the US dollar. Japanese equity markets are up 53% over the year to date. The economy has grown a solid 2.5% over nine months. Confidence is picking up and, importantly, inflation expectations are rising (see chart 3). This is not to say that there will not be challenges and risks ahead. Japan’s high public debt levels are largely sustained by capturing domestic funding, and the greatest risk is that a collapsing yen and negative real interest rates could result in a surge in outflows from domestic savers, bringing the government’s solvency into question.

It will be important to monitor Japan in 2014, as its experience could give central bankers and politicians in Europe in particular a game plan for jumpstarting their own economies.

The outlook for bond markets in 2014

Government bonds: a benign environment, despite tapering

As we approach 2014, financial markets are clearly in better shape than a year ago. Most equity indices are up for 2013, southern European sovereign bond yields are down sharply, and US Treasuries have rallied after the Fed’s surprise non-taper decision in September. But this positive outcome is not due to strong data or a long-term resolution of the European debt crisis. Growth is either below or close to trend levels in most economies, while asset prices have largely been supported by unprecedented levels of quantitative easing.

The Taylor rule

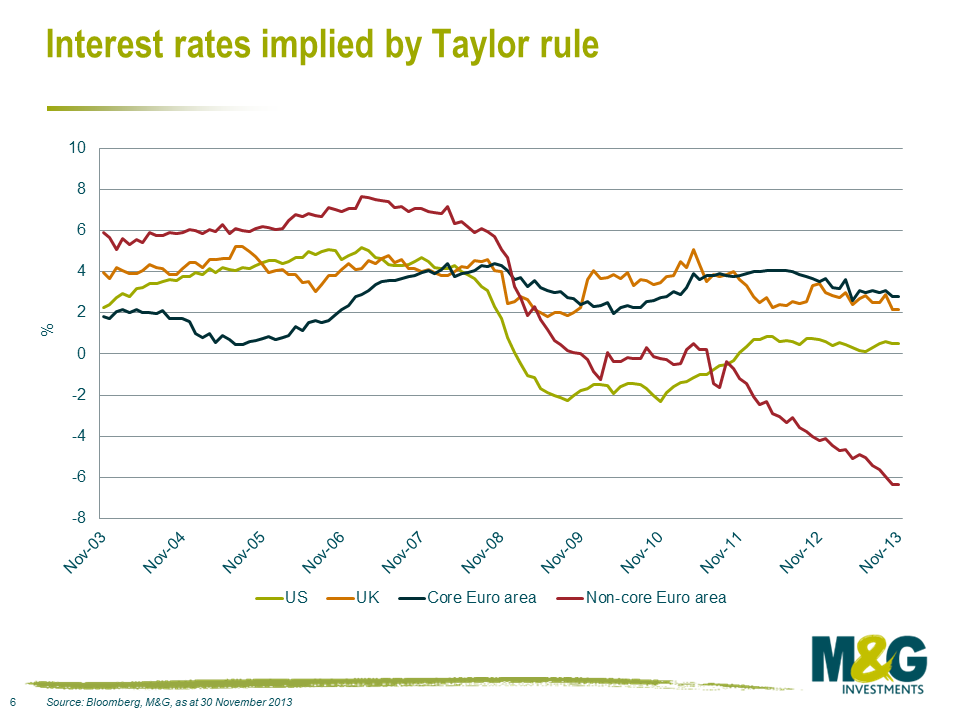

Ever since interest rates in the major developed economies hit the zero interest rate band, we have been interested in assessing what a Taylor rule for monetary policy would suggest for central bank rates across the US, UK and Europe. A Taylor rule is simply a monetary policy rule that suggests how a central bank should adjust interest rates in response to changes in inflation and macroeconomic activity.

The Taylor rule can be used to explain how policy has been set in the past, and whether the current monetary policy stance is appropriate for an economy. It can also serve as a guide for economists in determining the possible future policy path of interest rates. It appeals because it is relatively simple, and only requires knowledge of the direction of the current inflation rate relative to the target rate, and the output gap.

For the Fed, the rule rather nicely encompasses its dual mandate of maximising employment in the context of price stability. Although there are many versions of the rule, Yellen has shown a preference for the 1999 version, which, interestingly, has implied a zero or negative Fed Funds rate since late 2009.

The story is not dissimilar for the UK and Europe. Both regions surprised markets recently with lower than expected inflation (October CPI rates of 2.2% and 0.7% respectively). The Taylor rule would suggest that with inflation so far from the European Central Bank’s target of 2%, the bank should aggressively ease monetary policy, perhaps beyond November’s cut to 0.25% and even into negative territory.

The Taylor rule can be a useful rule-of-thumb for investors, enabling them to judge how short-term rates are likely to respond to changing economic conditions. Given that inflation has been falling recently, the Taylor rule implies that interest rates will remain low for longer (chart 6) – welcome news for us as bond fund managers.

Most regions still face very significant challenges in 2014, including very high levels of public and private debt. But with inflation expected to be muted and central bank rates likely to remain ultra-low, the environment for government bonds will remain relatively benign, despite higher yields and tapering-driven volatility. Whilst we acknowledge that there will be pressure on longer dated government bond yields to increase, we would caution against getting too bearish on the asset class, given that the short end of the curve will likely remain well anchored at current levels. Policy will remain highly accommodative, despite a slowly improving growth outlook.

Corporate bonds: recalibrate expectations

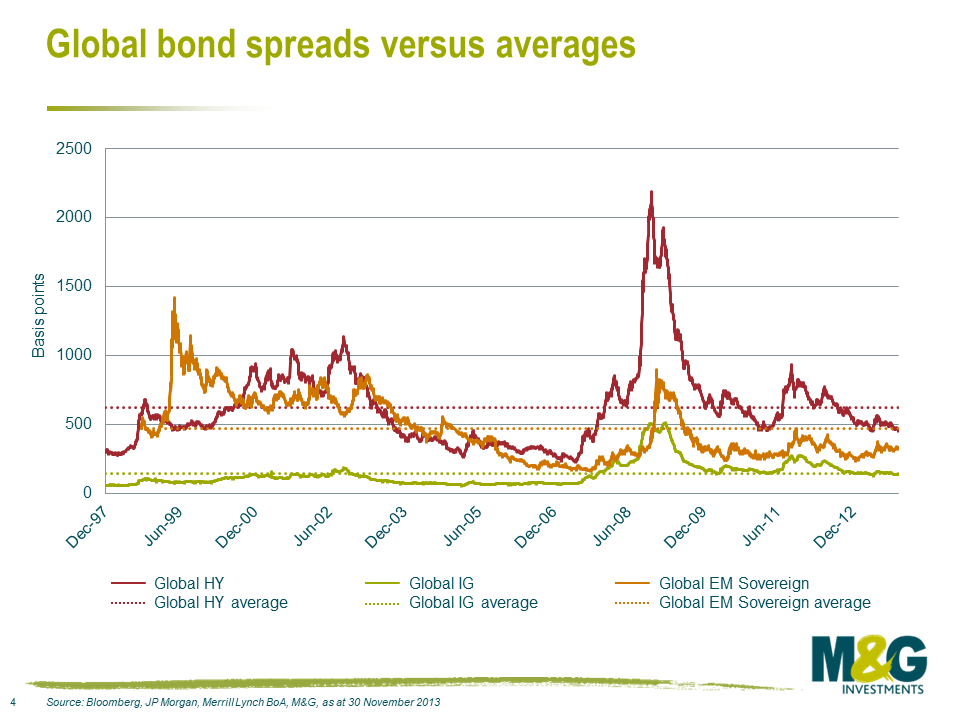

Corporate bond investors have experienced some excellent returns in recent years. The asset class has also benefitted from low volatility and broad-based inflows. With spreads heading back towards long-term averages (chart 4), some have questioned whether corporate bonds can continue to outperform, particularly in an environment of improved confidence and investor sentiment.

We believe the fundamental outlook for corporate bonds remains positive. With growth in the developed world recovering, defaults are likely to stay low. And, as already discussed, inflation is not a near-term issue. These two factors suggest that corporate bonds should remain a solid asset class for investors seeking good risk-adjusted returns.

After returning 5.2%, 10.8% and 0.3% in 2011, 2012 and 2013 (to end-November), investors must recalibrate their expectations for investment grade corporate bonds. The impending withdrawal of central bank support could create volatility in risk markets. In this sense, the tapering debate of 2013 gives us a guide to what to expect in 2014. However, with spreads starting the new year both tighter than in 2013 and close to historical averages, excess returns are likely to be lower. We believe most parts of the credit market will struggle to deliver much more than their coupon, but credit remains in favour versus other, even lower yielding, fixed income assets.

Investors in global high yield markets have enjoyed fantastic returns over the past couple of years, with total cumulative returns since 2012 of over 26%. This has resulted in a collapse in yields to close to record lows – from 7.7% in 2011 to 5.7% today. For us, high yield can be an attractive area of the fixed income market to generate returns in an environment of improving economic growth and low defaults.

But this should not mean that investors can rest on their laurels. The current benign environment for credit has led to a deterioration in the quality of issuance (as measured by credit rating and leverage), weaker structural protections like legal covenants, the return of pay-in-kind (PIK) bonds, and lower coupons on new issuance, which has resulted in lower future expected returns. We believe in some cases, particularly for lower quality high yield such as CCC rated bonds, credit spreads are not adequately compensating investors for the possibility that defaults could rise at some point in the future.

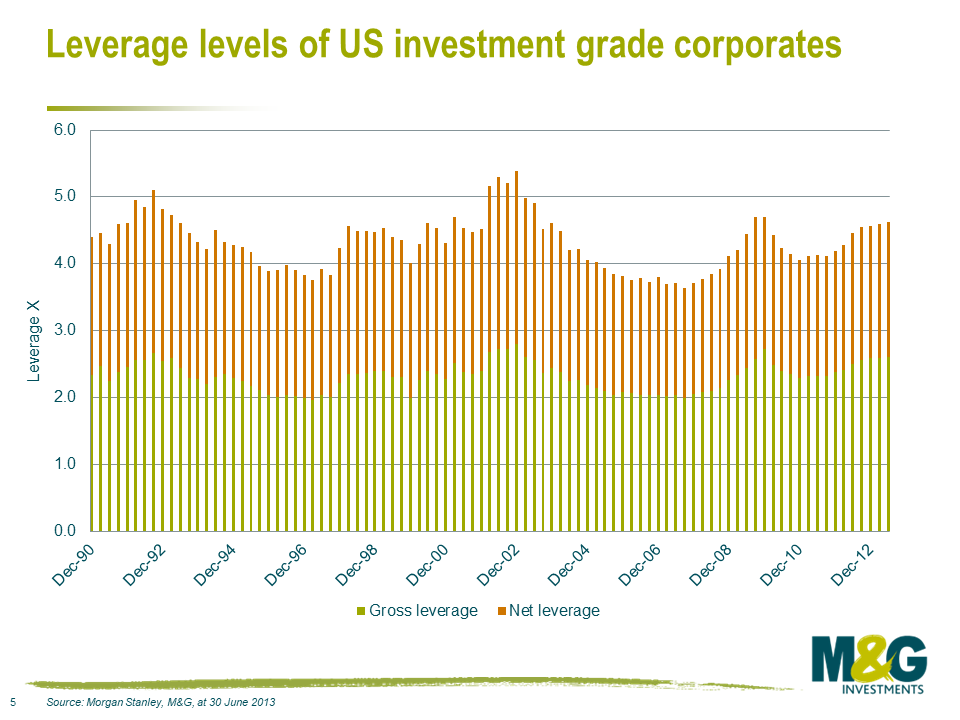

In such an environment, relative performance will be increasingly driven by single-name credit calls, and sector positioning will also be more significant than in recent years. It is more important than ever for bond investors and their credit analyst teams to do their homework, especially if the European credit market follows the US (as shown in chart 5) into an era of corporate re-leveraging and increased leveraged buyout risk.

Emerging market bonds: exercise caution

The potential re-pricing of US monetary policy is clearly the most serious risk facing global emerging markets in 2014. Outside this, we expect developments in China to dominate emerging markets. While the problems facing the Chinese economy are well documented, we think some investors may still be underestimating the risk of a slowdown. This could prove a costly mistake. China’s economy remains imbalanced: almost 50% of GDP comes from gross fixed-capital formation, up from a third in 1997. Massive excess capacity, high and rising corporate debt and an increasingly marginalised private sector are other symptoms of deeply rooted mismatches in the country’s economy.

It’s a knockout

Many have been quick to criticise the evolution in the Bank of England’s approach to monetary policy as advocated by its new Governor, Mark Carney. ‘Forward guidance’ – essentially making a promise about future interest rates – is now the foundation of central bank policy in the UK. The problem is the market has largely ignored the Bank of England’s promise that it will keep the base rate at 0.5% until unemployment hits 7%. As gilt yields and sterling have risen in anticipation of an earlier rate hike, financial conditions have become more restrictive. This could make economic growth harder to achieve – the very thing that the Bank of England is trying to avoid through its use of forward guidance.

The Bank itself recently told the market that it sees a 50% chance that unemployment will fall to 7% by the end of 2014, 18 months earlier than it had estimated in August. But unemployment is only one factor. The Bank has nominated three ‘knockouts’ which, if breached, would bring an end to forward guidance. These are based on inflation forecasts, inflation expectations and financial stability.

Of these, it is the 7% unemployment rate threshold that will likely pose the greatest challenge to continued forward guidance in 2014, given the recovery in the UK economy. If unemployment fell to this level, it would not necessarily trigger a rate hike, but it would bring about a re-assessment of monetary policy in the short term. Provided the other ‘knockouts’ remain relatively in line, we would not rule out a reduction in the forward guidance unemployment rate threshold to 6.5% or below.

We believe the knockouts all seem rather easily knocked out, which is a problem for the Bank of England. The market agrees and thinks that the Bank will end forward guidance early, despite Carney’s protestations. The tightening in financial conditions currently under way will likely result – with a lag – in a slowdown in the UK’s recent growth spurt.

We can see that Chinese policymakers understand the economy’s precarious position and are working to gradually defuse it. But we think that regardless of which reform path Beijing takes, more corporate defaults, rising non-performing loans, and some degree of a credit crunch are unavoidable over the next three years. Taking the experiences of, among others, the Soviet Union in the 1960s-70s, Japan in the 1970s-80s and southeast Asia in the 1980s-90s, a rebalancing of China’s economy away from investments and exports towards consumption will likely result in weaker GDP growth rates. China will still grow, it will still be a large number, but this number will be closer to 5%-6% than 10%.

Any slowdown in China would likely lead to a drop in emerging Asian currencies. We believe capital outflows and trade concerns could provoke up to 10% depreciation in local currencies. Implementing capital controls to stem outflows could arrest the slide, but we believe this is unlikely, given the long-term damage this would do to investor confidence.

If the Fed tapers in 2014, as expected, this will remove a key technical support from the emerging markets. Rising bond yields – even if range bound – and expectations of reduced asset purchases would likely drive the US dollar higher, hurting emerging equity markets and in turn driving credit spreads wider. Borrowers who need dollars could be doubly affected by this development. Meanwhile, any large-scale wobble in global investor sentiment could see the massive inflows of recent years reverse, with considerable consequences for investors as well as issuers.

As we mentioned earlier, no country – and this applies especially to the emerging markets – is entirely impervious to the Fed and its decisions. In the end, all roads lead back to the US.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

17 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox