Has globalisation peaked? If so, what are the implications?

“Inflation is as violent as a mugger, as frightening as an armed robber and as deadly as a hit man.”

If that is the case then developed economies have not encountered any muggers, armed robbers or hit men for some time.

That quote came from Ronald Reagan, candidate for US President in the late 1970s, back when controlling inflation was one of the biggest challenges for governments and central banks.

We are a world away from there today, where the bigger danger is deflation. Central banks and governments are doing their utmost to stimulate the economy by any means possible, including low/zero rates, buying back government debt and pouring out direct stimulus to combat the slowdown caused by COVID-19.

Where did the mugger go? Globalisation ended his career. One by one, as markets began liberalising, there were no pinch points for the mugger to exploit. From the single market in Europe and NAFTA in North America, to China (and the countless other countries that followed) becoming part of the WTO, measures were put in place to ease the flow of capital and goods across borders or remove them altogether.

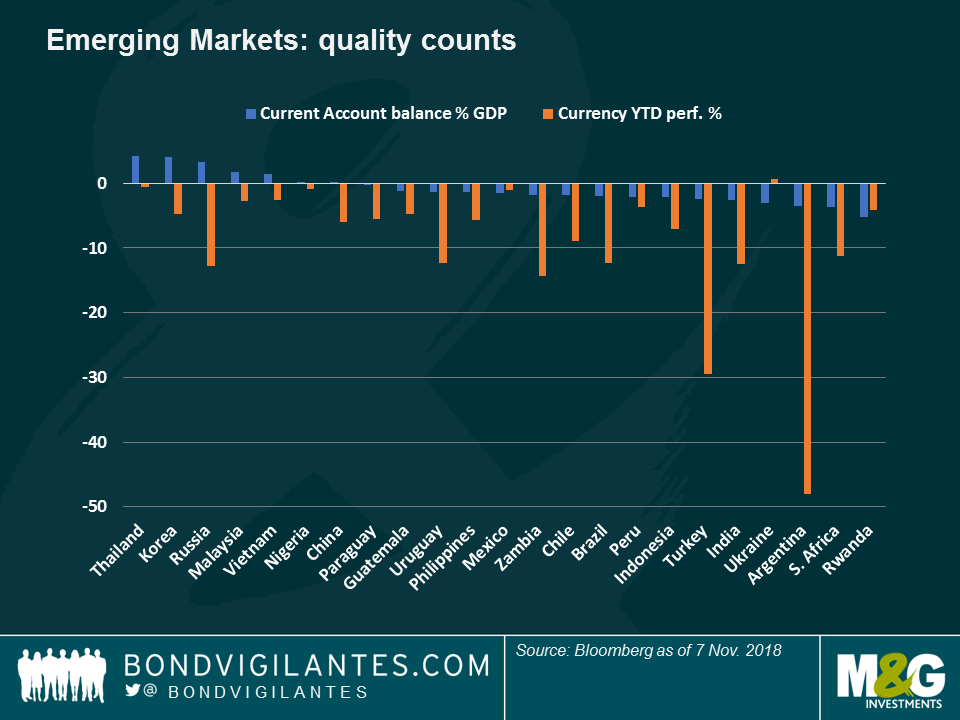

The 10 year US Treasury yield peaked at 15.7% in October 1981, and has been on a downward trajectory since with deflationary pressures muted. Global supply chains grew, costs were kept under control, and for every Thailand that developed and saw cost pressures rise, a Bangladesh would enter the family of global nations and offer the mugger no respite.

The landscape had begun to shift before the world had ever heard of COVID-19. While freeflowing movement benefitted the owners of capital, there were parts of the labour market that had seen wage deflation for nearly 25 years. These are the groups now voting for Brexit in the UK, Front Nationale in France, Matteo Salvini in Italy, Donald Trump in the US, Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil and Rodrigo Duerte in the Philippines.

A retrenchment of global supply chains already had the potential to recreate domestic inflationary pressure. And then along came COVID-19. With dramatic effect, the virus has shown the weaknesses in global supply chains and, for the first time post World War II, led to governments all across the world closing their borders and airspace.

A long term consequence of this global pandemic may be that localisation of supply chains becomes prominent again, both from companies and from governments which will prioritise security and accessibility over costs.

Going big… and the Treasury bear

‘If you’re going to go big, just go big.’ Republican President Donald Trump told Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin, who put together a $1 trillion stimulus package in the US last week.

Wanting a quick passage, the Democrats added a further $1 trillion to the package to guarantee its immediate approval. There we have the largest stimulus package in US history, nearly three times the size of the TARP (Troubled Asset Relief Program) package introduced in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis.

The financially conservative German government followed with a €750bn stimulus package of their own. Meanwhile, the EU suspended the debt and deficit requirements across the European bloc. There have been countless more such measures all across the world.

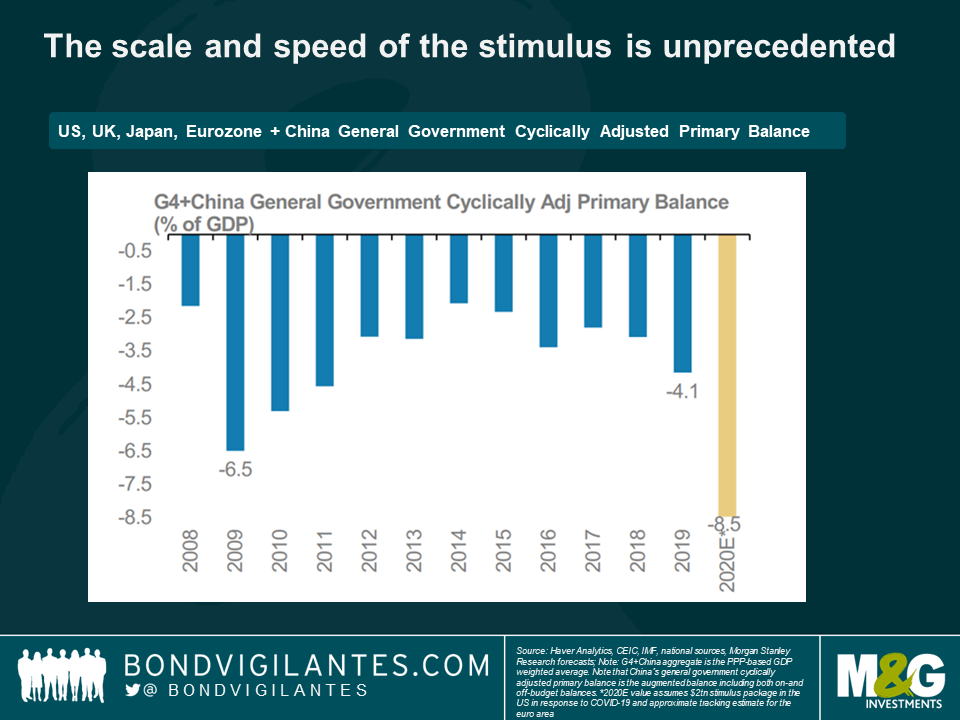

While stimulus measures are required in times of large unexpected shocks, the scale and speed of the stimulus we have just witnessed is unprecedented. The economic costs of COVID-19 are still unknown: policy makers have thrown caution to the wind and planned for the worst case scenario.

Should the slow but increasingly important trend of trade barriers begin to rise, and there be excess stimulus in the world economy once we have returned to some level of normality, we are likely to see some longer term economic implications.

The death of the more than 30-year bull market in US Treasuries has been predicted many times. It will require sustained inflation in the system to force longer term interest rates up. While our minds could not be further away from that thought today, the ingredients for this eventuality are all just going in to the mix.

Policy choices have unintended consequences, especially when they are made in times of extreme pressure. For those who are scared of muggers, please take note.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

17 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox