Being an Australian sporting fan hasn’t been easy during my time at M&G over the past five years. The Olympics, rugby, cycling, cricket, tennis… Britain’s golden-age of sport has coincided perfectly with the decline in Australia’s sporting prowess. On top of this, I had the misfortune of seeing my premier league team get relegated last season (though there are definite green shoots of recovery emerging for QPR) and I am about as excited about the upcoming Ashes series as someone who has just been told that they need root canal surgery.

It has now got to the stage that my British colleagues – with memories of their national sporting teams’ performances during the 90s in the back of their minds – have taken pity on me, stating that it’s all cyclical. It’s enough to make you cry into a snakebite down at the Walkie (there’s only one left in London!).

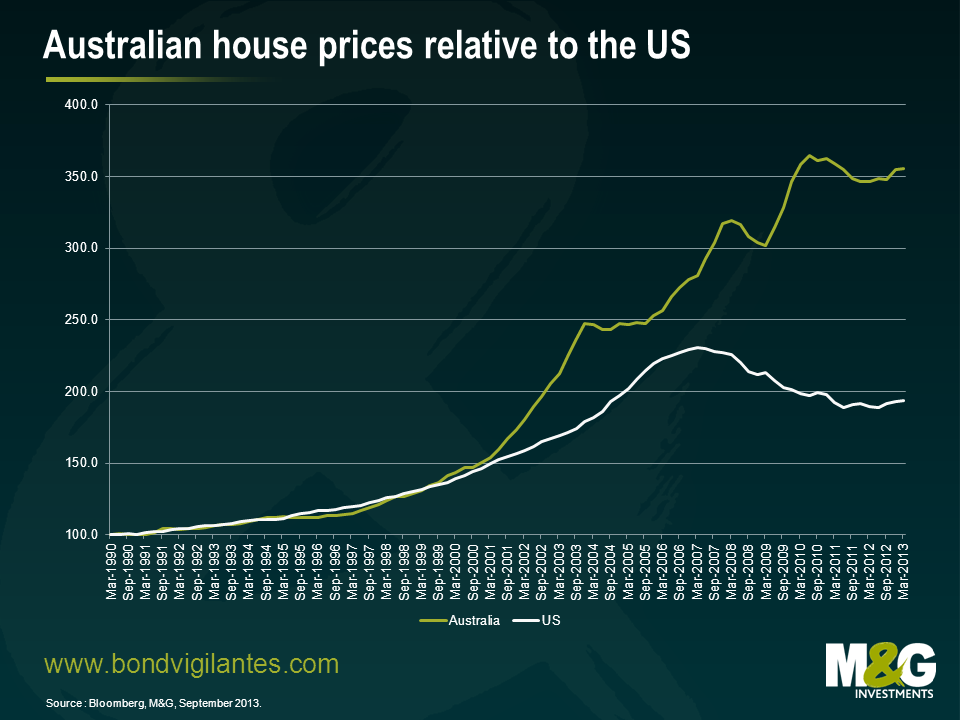

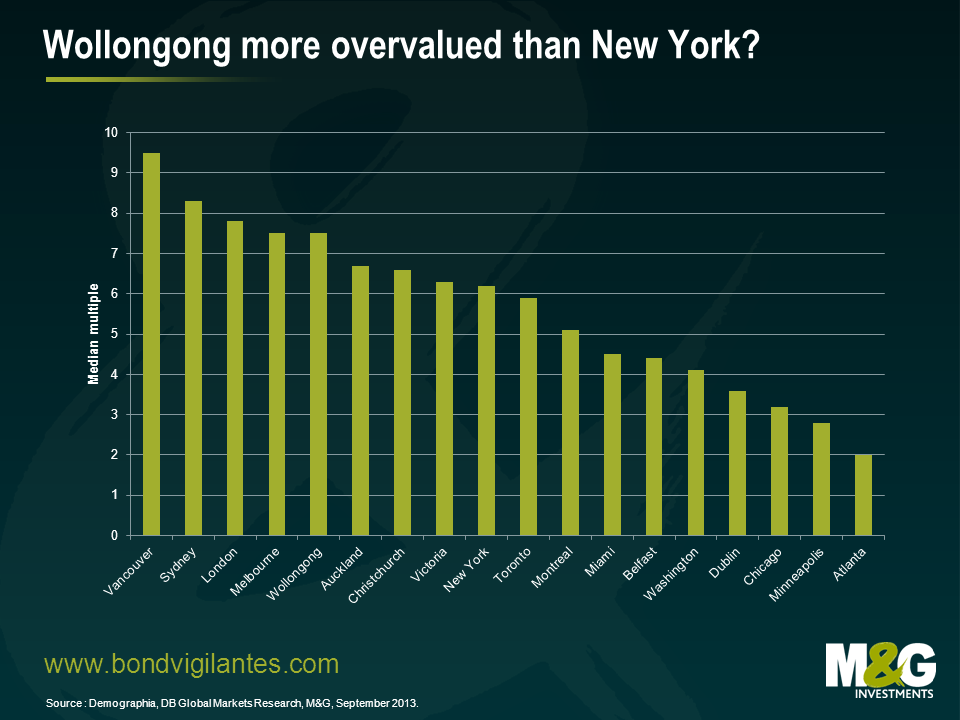

One thing that hasn’t been cyclical is the Australian housing market. House prices seem to go only one way, and that’s to the moon. Australians haven’t had much to talk about on the sporting front in recent years, so most of the chat at BBQs has turned to properties (“How many do you own?”) and prices (“Get your feet on the housing ladder”). The increase in Australian house prices far exceeds the land of sub-prime loans (the US) and goes some way to explain why Sydney, Melbourne and Wollongong are more expensive on a median multiple basis than New York, Miami and Washington.

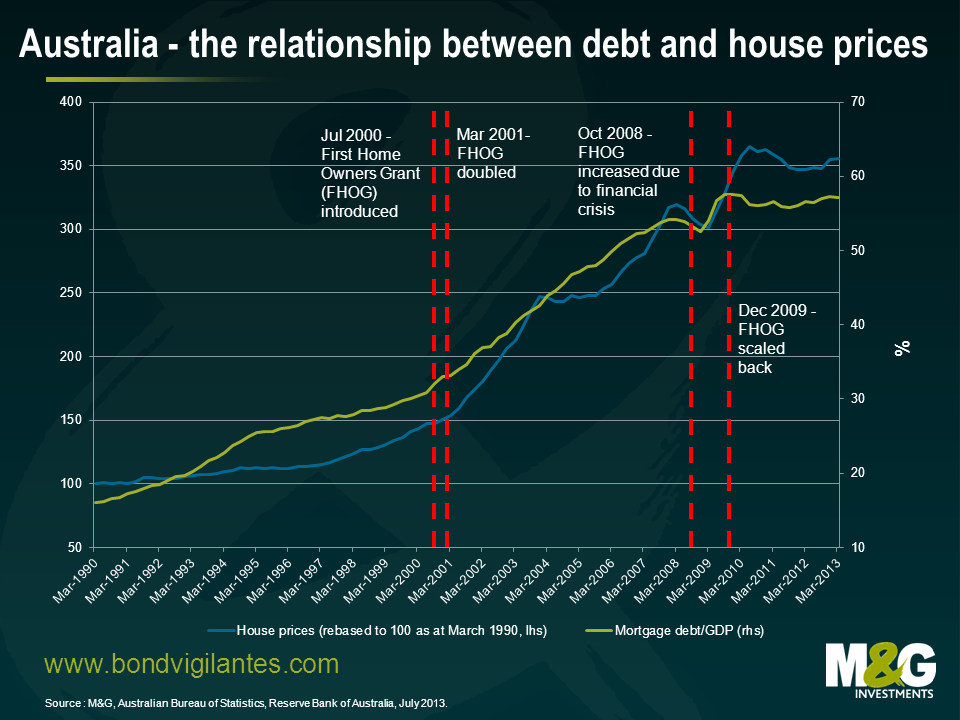

Twenty-one years of sustained economic growth, low unemployment and the boost to incomes that has come from a record increase in Australia’s trade, have lulled most of the population into a false sense of security that house prices will never go down. There is a well-known rule in Australia for property investing – prices double every 7-10 years. Absolute madness. Throw into this economic bonfire the most favourable tax treatment of property investments in the world and record low interest rates and it’s easy to see why there is a clamour to own bricks and mortar. Not only as a source of shelter but also as a retirement policy. The blinkers have been well and truly fixed to the Aussie home buyer.

We have written before that the Australian housing market worries us (see here, here and here). And with confirmation last week from the regulator that Australian financial companies have lent $1.13 trillion AUD in residential loans to facilitate the increase in house prices we are even more worried. In the background, national papers have been reporting that auction clearance rates have been higher than 80% for almost two and half months and that Chinese buyers are increasingly entering the market due to government restrictions on purchases at home.

The regulator must keep an eye on debt levels and the quality of banks loans to individuals. In Q2 2013, financial institutions lent $79bn to home buyers. $31bn of this was interest-only and low-documentation lending. As we all know this is the area where mortgage delinquencies will first occur in an economic downturn. In Australia, there is a close relationship between debt/GDP levels and house prices. Should the banks be forced to rein in lending, we could see some big ramifications for the housing market pretty quickly.

Australian housing is showing all the signs of a bubble. When lenders start resorting to the cute little kid to shift 95% loan-to-value mortgages you have to wonder how much longer this can go on.

How has the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) reacted to this asset price bubble and the risks that it poses to financial stability? By stating that there is no bubble. Dr Malcolm Edey, who is responsible for financial stability at the RBA, stated last week that: “We’re in one of the higher-than-average periods at the moment, but we shouldn’t be rushing to reach for the bubble terminology every time the rate of increase in house prices is higher than average, because by definition that’s 50 per cent of the time. You’re just going to be unrealistically alarmist by making that call every time that happens.” So it appears the RBA, much like the Federal Reserve in the US under Alan Greenspan, would be very hesitant to raise rates to reduce any “froth” that may develop in areas of the Australian housing market.

It is easy to see why the RBA would avoid such an action. Higher rates, in a world where interest rates are near zero in the developed markets, would drive the AUD higher and reduce whatever little competitiveness the manufacturing and export sector had after years of an overvalued AUD in a globalised economy.

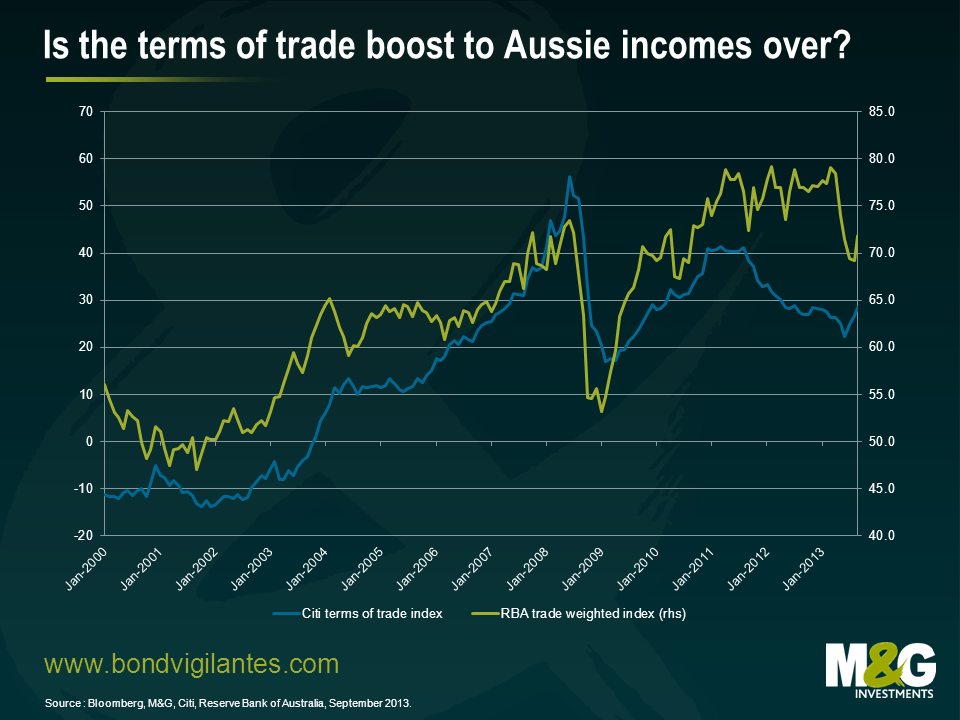

The catalyst for any house price correction in Australia will be the labour market. And leading indicators aren’t great. The Australian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy released a report yesterday showing that unemployment amongst its members had increased from 1.7% in July 2012 to 10.9% in July 2013.

Unlike the RBA, we think that it is time to be alarmist, particularly given our concerns around China. More than a decade of digging stuff up and shipping it to China has left Australia with all the telltale symptoms of Dutch disease. The mining industry is not only one of the largest employers in the country, it is famously one of the best paying as well (who hasn’t heard the anecdotes of cleaners being paid $100k a year to clean the miners living quarters?). Should the resources boom fizzle out, as it most likely will in conjunction with a China slowdown, hundreds of thousands will face losing their jobs across the economy. Not only that, we will see a massive impact on consumption within the economy as consumers tighten their belts to try and pay their ultra-high mortgage payments (Aussies will have to quickly deploy the savings they have been building up – the household saving ratio has increased from -2.4% in 2002 to 10.8% today). With unemployment and mortgage defaults rising, the RBA will hit the zero interest rate bound and embark on quantitative easing quicker than you can say “why didn’t we see this coming?”

Most economists see an orderly rotation away from the mining sector as the driving force of the economy to the services sector. The main reason they point to is that a sharply lower AUD should allow sectors like manufacturing and tourism to thrive again. In terms of the housing market, many point to significant under supply and full recourse loans as protection against a meaningful correction in Australian house prices to saner levels. The consensus expects modest gains in house prices for the foreseeable future.

Personally, I am not so sure. Can we really expect a hollowed out manufacturing sector to soak up the excess workers that the mining sector is shedding at a record rate? Remember when central bankers told us the sub-prime crisis was contained? Or the tech boom of the late 90s when everyone was an I.T. expert? Or perhaps it was that developments in Thailand were unlikely to spread and affect developed markets in 1997?

I’ll put my hands up; I’ve thought that a meaningful correction has been coming for at least the five years I’ve been in London. But I haven’t been as convinced as I am today that we are close to the end. There is enough evidence to suggest that Australian central bankers and policymakers should be greatly concerned and the absence of any meaningful debate in the recent election suggests there is limited political will to address any housing affordability problems that Australia is experiencing. I am amazed that young people all over Australia have not made more of an impact on the national debate on house prices. But then again, those born in the 80s and 90s think that rising house prices and economic prosperity is a way of life, so why not borrow eight times your income and leverage yourself up to buy your first house? You can always sell it in five years’ time and buy a better one.

Australia’s national sporting teams may recover from their current downturn. Hopefully the cricketers will in time for the Ashes which begin in November. Whether the Australian economy can survive the double-whammy of a China slowdown and housing correction is another story.

Despite high unemployment rates, excess capacity and a sanguine inflation outlook from the major central banks, it is important to keep an eye on any potential inflation surprises that may be coming down the line. For instance, we only need to look at ultra easy monetary policy; low interest rates and improving economic growth to see that the risk of an unwelcome inflation shock is higher than perhaps at any time over the past five years. The development of forward guidance measures is a clear sign that central banking has evolved substantially from 2008 in the form of Central Bank Regime Change. It appears that there is a growing consensus that inflation targeting is not the magical goal of monetary policy that many had once believed it to be and that full employment and financial stability are equally as important. Given that monetary policy appears firmly focused on securing growth in the real economy – at perhaps the expense of inflation targets – we thought that it would be useful to gauge the short and long-term inflation expectations of consumers across the UK, Europe and Asia. The findings from our August survey, which polled over 8,000 consumers internationally, is available in our latest report here.

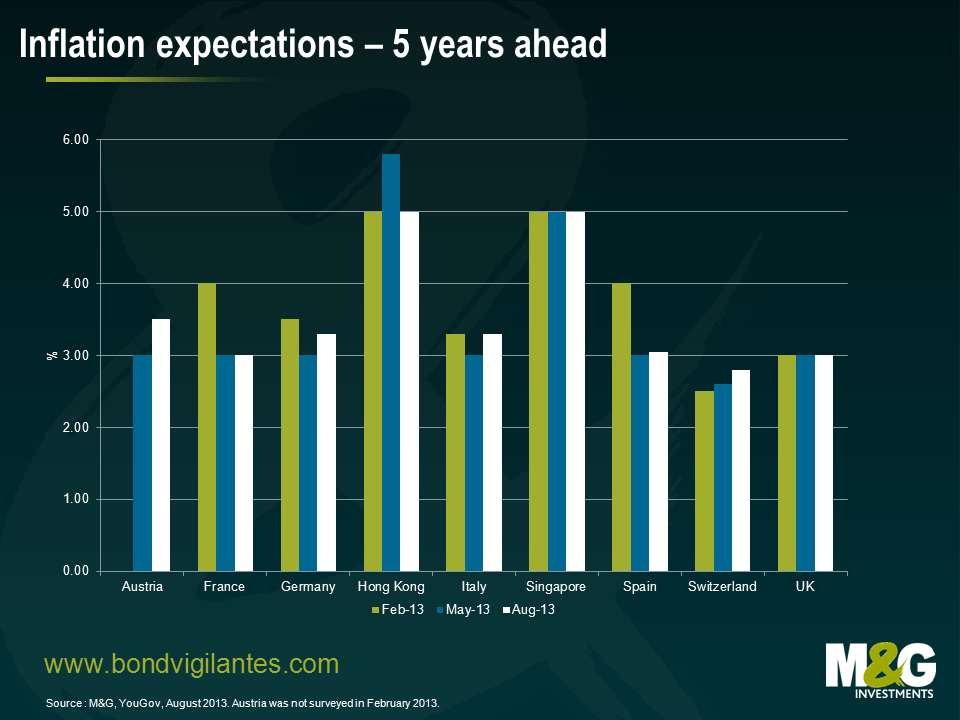

The results suggest consumers continue to lack confidence that inflation will decline below current levels in either the short or medium term. Despite evidence that short-term inflation expectations may be moderating in some countries, most respondents expect inflation to be higher in five years than in one year. Confidence that the European Central Bank will achieve its inflation target over the medium term remains weak, while confidence in the Bank of England has risen.

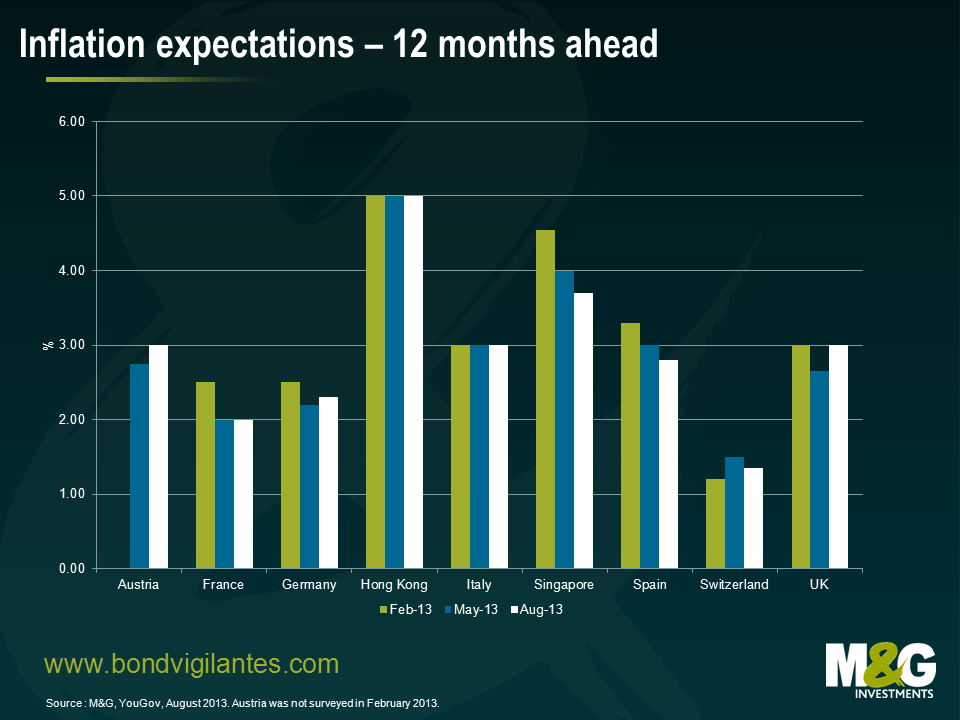

The survey found that consumers in most countries continue to expect inflation to be elevated in both one and five years’ time. In the UK, inflation is expected to be above the Bank of England’s CPI target of 2.0% on a one- and five-year ahead basis. All EMU countries surveyed expect inflation to be equal to or higher than the European Central Bank’s HICP target of 2.0% on a one- and five-year ahead basis. Long-term expectations for inflation have changed little in the three months since the last survey, with the majority of regions expecting inflation to be higher than current levels in five years. Five countries expect inflation to be 3.0% or higher in one year: Austria, Hong Kong, Italy, Singapore and the UK.

Consumers in Austria, Germany and the UK have reported an increase in one year inflation expectations compared with those of the last survey three months ago. This is of particular relevance for the UK, where the Bank of England has stated three scenarios under which the Bank would re-assess its policy of forward guidance. The first of these “knockouts” refers to a scenario where CPI inflation is, in the Bank’s view, likely to be 2.5% or higher over an 18-month to two-year horizon. Short-term inflation expectations in Singapore and Spain continued their downward trend in the latest survey results, registering their third straight quarter of lower expectations.

Over a five-year horizon, the inflation expectations of consumers in Austria, Germany, Italy, Spain and Switzerland have risen. Whilst inflation expectations in Switzerland remain at the lowest level in our survey at 2.8%, consumers have raised their expectations from 2.5% in February. Long-term inflation expectations in France and the UK remained stable at 3.0%. Meanwhile, consumers in Hong Kong and Singapore have the highest expectations, at 5.0%, although the Hong Kong number shows a decline from 5.8% three months ago.

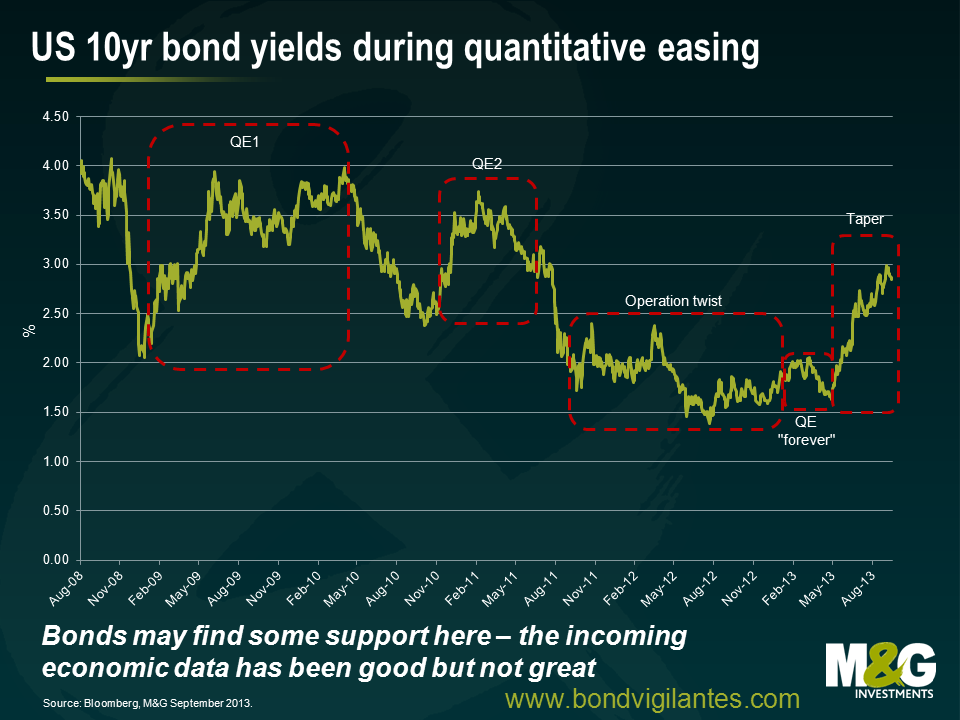

Last night the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) delivered a massive surprise by deciding to not taper QE. For us, this isn’t a huge deal. Since May, the market has placed way too much emphasis and concern over tapering and lost focus on the fundamental economic situation that the US has now found itself in – an economy where unemployment has fallen to 7.3% (helped by a falling participation rate) and a central bank that remains dovish due to a declining trend in core inflation. Now we are through the Fed meeting, arguably the market will now re-focus on the economic data. With interest rate policy set to remain very accommodative for a long period of time – even after balance sheet neutrality has been achieved – the sell-off in government bonds may be close to coming to an end (as witnessed by the 19bps fall in the US 10 year yield from 2.89% yesterday afternoon to 2.70% this morning).

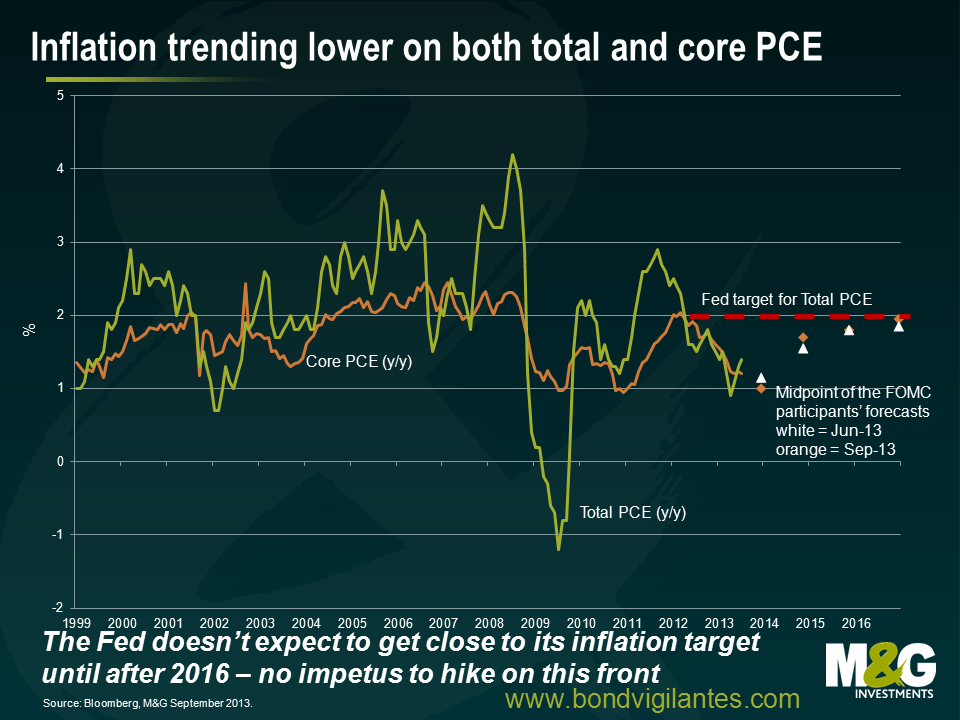

Fed concern number 1: US core PCE inflation is flirting with historic low levels

It is well known that FOMC Chairman Ben Bernanke, a student of the US economic depression of the 1930s, has great concerns about deflation and in 2002 gave a speech outlining how the US could avoid a deflationary trap which gave him the moniker “Helicopter Ben”. In the speech, Bernanke makes the important statement that “…Congress has given the Fed the responsibility of preserving price stability (among other objectives), which most definitely implies avoiding deflation as well as inflation.”

The Fed’s preferred inflation measure, the core PCE, is exhibiting a worrying downward trend. This greatly concerns at least one member of the FOMC – St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank President James Bullard – who believes the FOMC should have more strongly signalled its willingness to defend its inflation target of 2 per cent in light of recent low inflation readings. The Fed minutes from the June meeting (at which Bullard dissented) showed that Bullard believed that the Fed was not doing enough to protect against the threat of deflation and that the FOMC must defend its inflation target when inflation is below target as well as when it is above target.

A key component of the Fed’s dual mandate – price stability – is clearly below where the FOMC wants it to be. There are big risks to reducing stimulatory monetary policy when core inflation is running at recessionary levels and on this measure suggests any interest rate hikes a long way away.

Fed concern number 2: the labour market

The latest payroll report was weaker than market economists had become used to, with payroll growth averaging around 148,000 over the past three months. This is some way off the 200,000+ numbers that the consensus was expecting earlier in the year and confirms a deceleration in the trend in nonfarm payroll growth. Yes, the unemployment rate fell to 7.3%, but this was largely the result of the labour force shrinking and a decline in the participation rate in August. The labour market is not as strong as the headline number suggests.

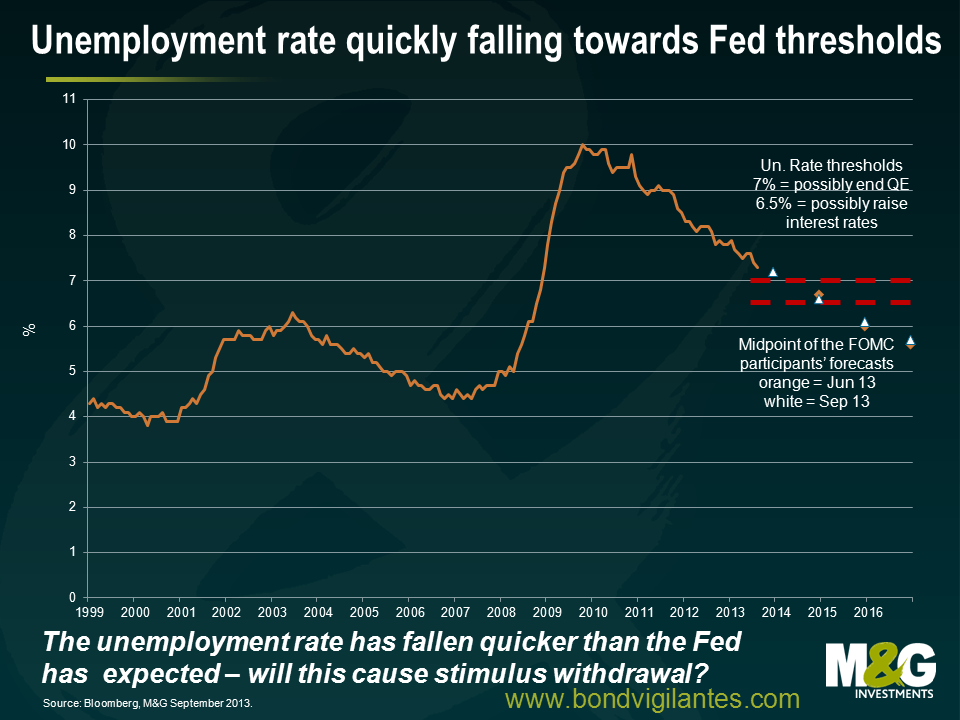

Arguably, the fall in the unemployment rate has surprised most Fed members. Nonetheless, unemployment is not expected to fall to the 6.5% “think about raising interest rates” level until late 2014. It would have been a confusing message to start to implement tapering given the lower trend in job creation. The Fed reiterated that the economy and labour market have to be strong enough before in contemplates reducing asset purchases going forward. This helps to explain why the FOMC sat on its hands in September.

Fed concern number 3: the increase in mortgage rates

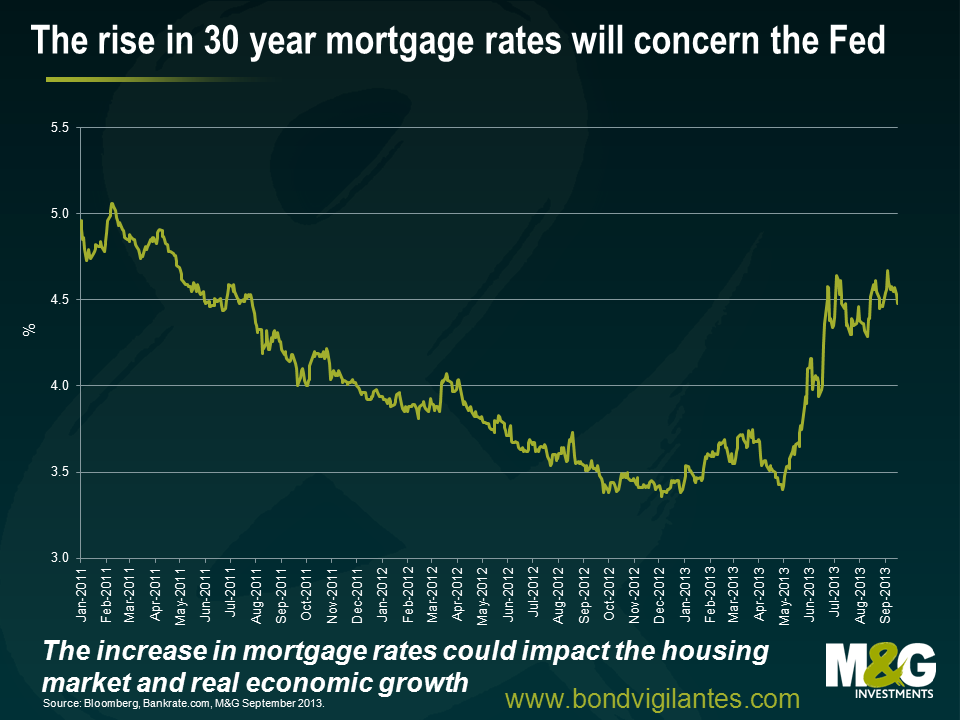

Following the moves in markets over the summer, the average rate for a 30-year fixed mortgage has now increased to around 4.5% from 3.4% in May. Essentially, the market has already tightened for the Fed. The housing market is a vital component of US economic growth, and this increase will cut into housing affordability. It could also force potential homebuyers out of the market. A slowing housing market means fewer jobs, less consumption, and lower growth. The increase in yields in the government bond market has been brutal, and does pose some risks to interest-sensitive sectors.

Given the above, it appears that the Fed refused to be bullied into tapering today by the bond markets, though tapering speculation may have reduced the “froth” that had developed in risk assets over the first half of 2013. It is likely that low inflation, a recovering labour market, and a slowing housing market will ensure that interest rate policy remains accommodative for the foreseeable future. The “Fed fake” suggests that tapering is truly data dependent and not predetermined. Macro matters.

As the market begins to refocus on the economic data, it is likely that government bonds may find some support. Additionally, the FOMC may reduce bond purchases slower than anyone currently expects. We expect that market concerns over the impact of tapering decisions will likely diminish over time as the Fed slowly and gradually moves towards a neutral balance sheet policy next year.

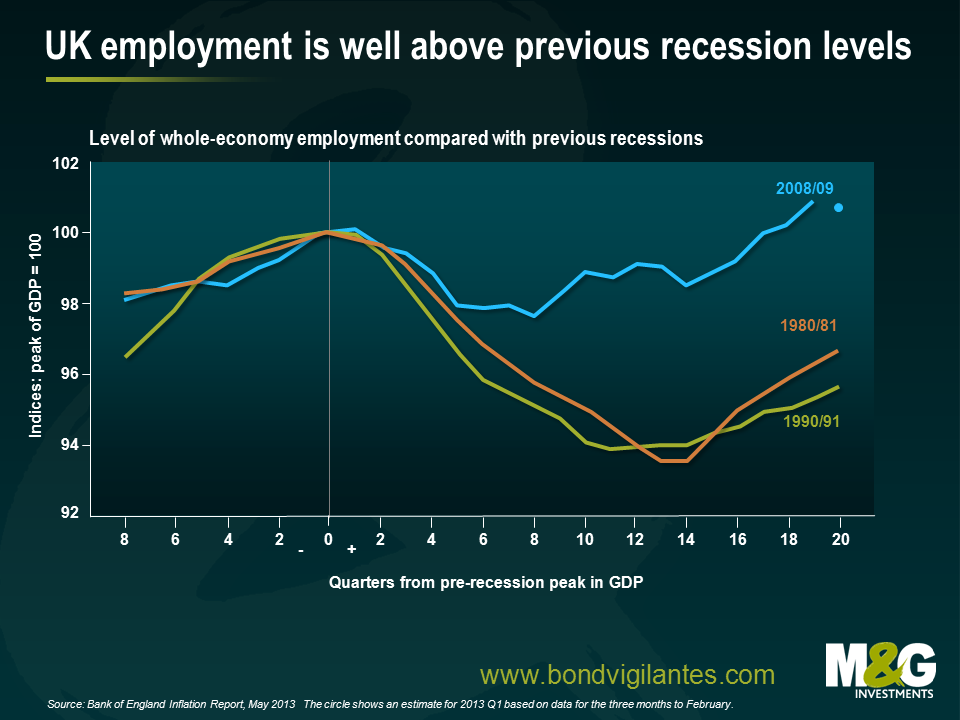

When meeting UK clients we obviously spend a lot of time discussing employment and the relative strength of the UK economy. The chart below from the Bank of England shows the recovery in employment in comparison to previous recessions. It actually looks quite good versus the other mega recessions.

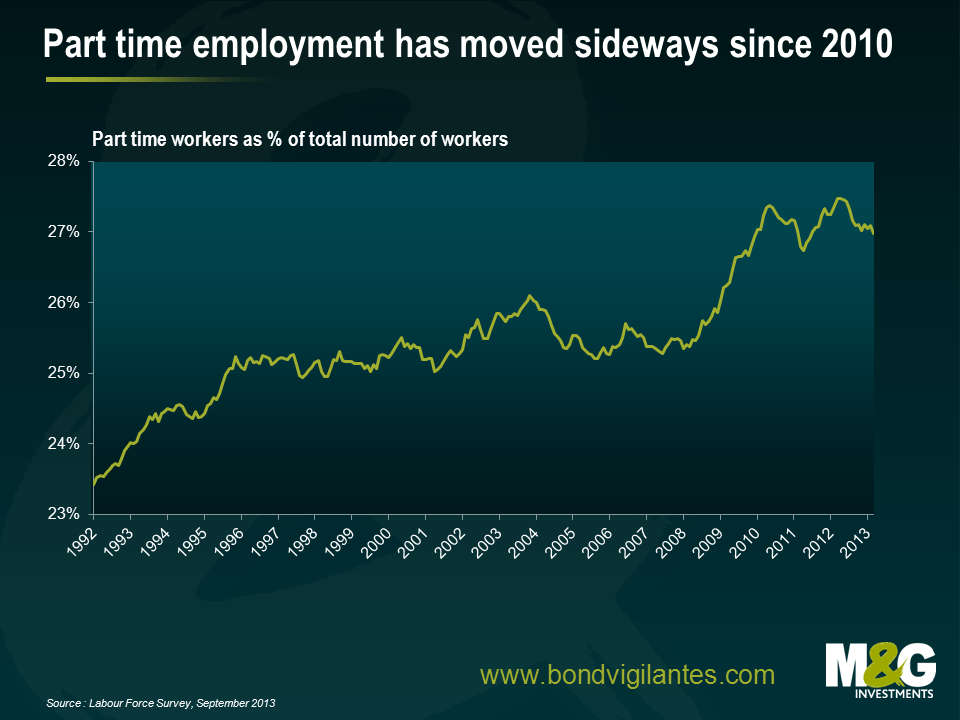

One very good common question we often get is along the lines that the employment number is “not real” as part time employment has gone through the roof.

The chart below shows part time employment as a percentage of the total number of workers in the UK. There is obviously an ongoing trend to part time employment that has continued from the peak of the crisis. It appears that part time employment increased relatively rapidly through the recession. However, since 2010 the ratio has been declining. Therefore the recent recovery in employment appears genuine and not flattered by part time workers.

The UK economic recovery is real, and thankfully fiscal deficits, and interest rate policy have worked. The market’s fears of permanent recession are diminishing as reflected in the current bear market for UK gilts. The economic panic illustrated by very low yields where gilts became very dear (see this blog from January 2012), is over. The gilt market yield is returning towards better value, with ten year yields once again around three percent, as the UK economic recovery remains firmly on track.

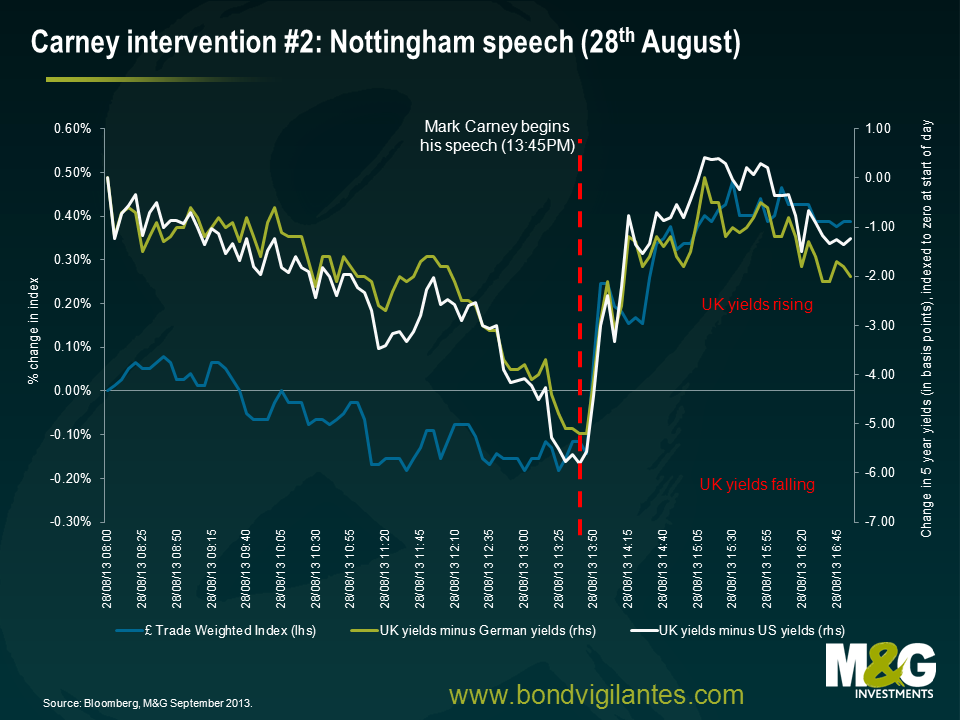

“Now, much has been made of the upwards movements in market interest rates since our announcement of forward guidance and I would like to give you my perspective. There’s been a generalised upward movement in long term bond yields, across the advanced economies, including the UK, over the course of the past month. The main common driver is speculation that the US Federal Reserve will soon reduce the pace of its asset purchases (and) …. liquid sovereign bonds of the world’s largest economies are close substitutes for each other”.

Bank of England Governor Mark Carney in the “Jake Bugg” speech, Nottingham, 28th August.

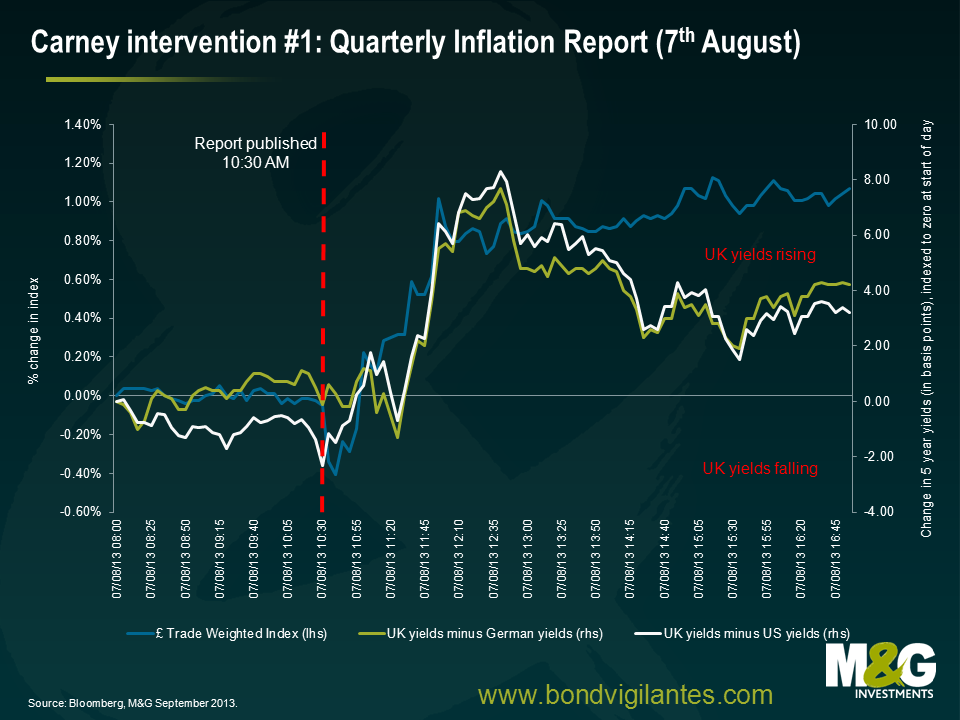

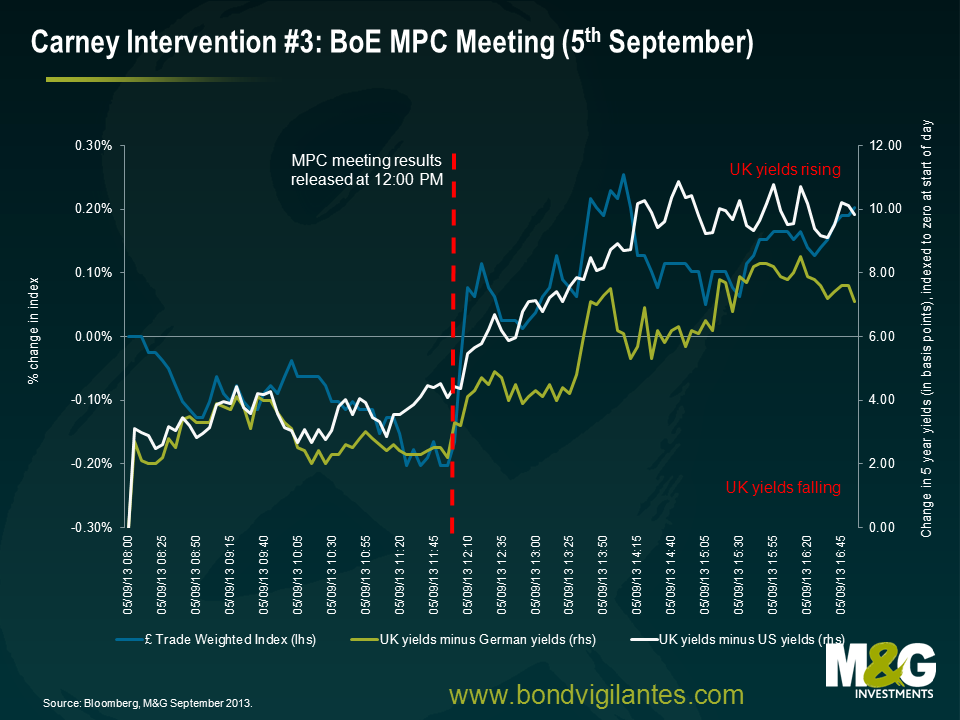

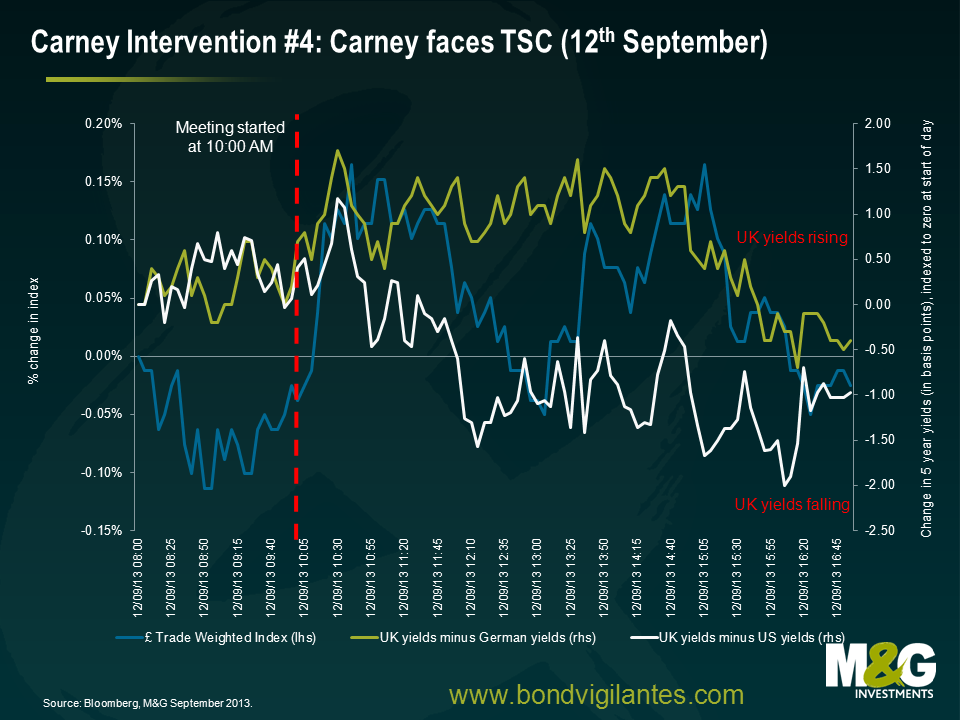

In other words, according to Mark Carney, gilts sold off because treasuries sold off. Personally I do not share this view, and feel some of the blame also lies with the Bank of England. Indeed, if we look at the aftermaths of the 4 occasions of Carney writing or talking about forward guidance (the August Inflation Report, the Nottingham Speech, the BoE Monetary Policy Committee Meeting, and at the Treasury Select Committee), we see that in each instance the pound appreciated markedly and gilts underperformed.

Put together, the result so far of forward guidance has therefore been a tightening in UK monetary policy – Governor Carney said last week that monetary policy has become more “effective” as a result of guidance. Perhaps, but only if you thought the UK was overheating, and this does not appear to be his, or other MPC members’, position.

7th August: the Inflation Report is published.

The August Inflation Report contains the forward guidance that the Chancellor commissioned in the Budget. It said that rates would be no higher than 0.5% until unemployment was down to 7%, and that the Asset Purchase Facility wouldn’t shrink. But it contained the three killer knockouts – that you could ignore forward guidance if the Bank’s forecast of inflation rose to 2.5%, if market/consumer inflation expectations became unanchored, or if there were risks to financial stability as a result of low rates. The market focused on these knockouts rather than the unemployment promise. Sterling rallied and gilts underperformed both US Treasuries and German bunds.

28th August: the Nottingham speech.

There was no mention of the famous knockouts in this speech and the tone tried to be dovish. But there was a repeat in both the performance of the currency (a rally) and the gilt market (an underperformance). These same trends are also exacerbated when the Bank of England’s MPC makes its “no change” rate/QE announcement on 5th September without any attempt to reinforce the commitment to forward guidance.

12th September: the Governor and MPC members appear in front of the Treasury Select Committee.

Not so strong this one – there was a reaction initially from sterling, and to a lesser extent gilt spreads. But they weren’t especially long lived.

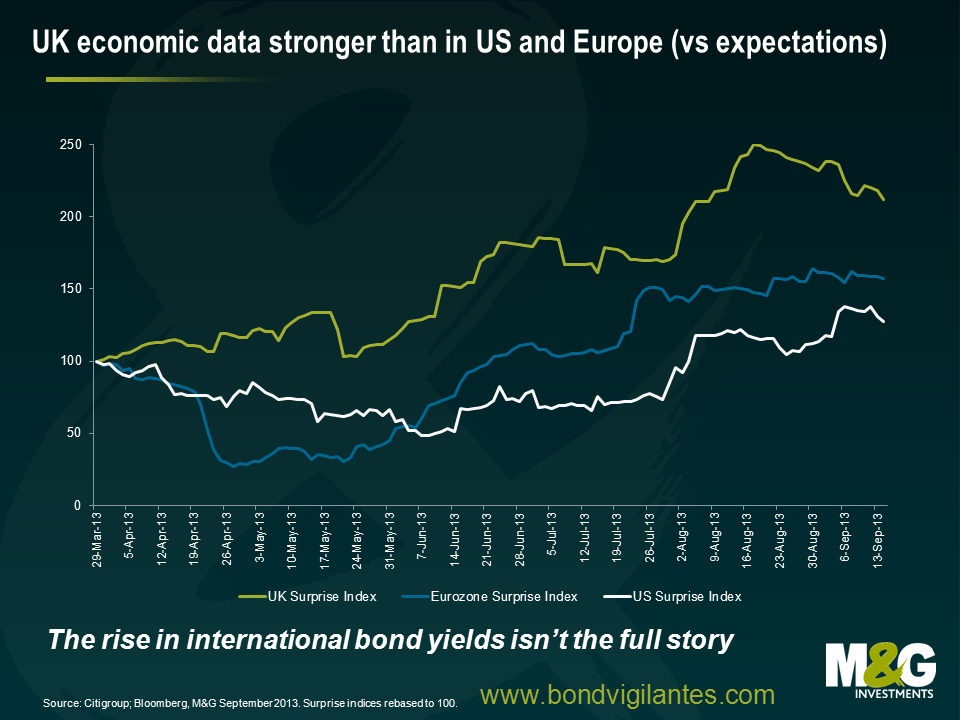

So I have no sympathy for Mr Carney’s view that forward guidance isn’t working because of the adverse movements in the pesky international bond markets – gilts have underperformed both bunds and treasuries, and the appreciation in the pound suggests that the markets think that Carney’s central expectation of three years without a hike is wrong. But in the Nottingham speech, Mr Carney also suggested that another explanation for rising gilt yields is that “the markets think that unemployment will come down to 7% more quickly than the Bank does…that would of course be welcome”. This is credible. We look at economic surprise indices, and it is clear that around the time of the publication of the August Inflation Report, the UK economic data started to not only surprise on the upside, but to be even more upwardly surprising than the (also better than expected) economic data coming out of both the Eurozone and the US. It’s a combination of the lack of clarity around the knockouts (made worse at last week’s TSC – I recommend you go along to watch this live if you get the chance by the way) and an expectation that the Bank’s unemployment forecast is overly bearish. Of course the rise in international yields is important, but it’s not the full story.

So the timing of sterling rallies and gilt underperformance around the time of Bank communications suggests that they ARE getting something wrong, and the grilling in front of the TSC did not go well. If I were them I wouldn’t try to use open mouth policy to try to reverse the trends we’ve seen, as it could lose them more credibility were the markets not to react positively. Doing something is another matter though, and could lead to a big reversal in the gilt and currency markets. As UK economic data improves and surprises on the upside I doubt we’ll see anything yet – but we do need a little less conversation and a little more action.