Italy: the good, the bad and the…politicians

Italian politics has been in the international news, again. Markets tend to fear instability and Italy is always a creative and boundless source of uncertainty. We Italians have a wonderful ability to put ourselves into trouble. The good news is that markets in recent weeks have held up more than in the past.

1 – Political life in the peninsula

In the last few weeks, research from many well-known investment banks has identified Italy as one of the two major global sources of near-term risk for capital markets (the other being the US shutdown). The crisis started when Mr. Berlusconi asked his ministers to resign from the government in order to push for new elections. However, against expectations, the risk dissolved almost as quickly as it appeared when Mr. Letta won the ensuing confidence vote with large support. While this was good news, what is next in store for Italian politics? While I can’t forecast the future, I can say that Italy will never change in this sense. Uncertainties around party and electoral laws, social policies, public debt, tax evasion, structural reforms, trade interests and inefficient regulations (to name just a few) will be around for a long time in a nation that is incapable of moving quickly. While political risk will remain a source of noise, investors excessively focused on it may miss the bigger picture, both on the downside and on the upside.

2 – Bad news first: above and beyond the “Res Publica”

In the land where the ancient Roman Empire began, several economic problems have lingered for decades. Public debt at EUR 2 trillion (of which around 30% is non-resident holdings, according to IMF Dec 2012 numbers) is enormous with a debt/GDP number worryingly on the rise. The key concern for investors should be the implication of carrying such a high interest expense, together with the overall amount of public spending. The Italian system – including salaries for public sector employees, general benefits, ongoing expenses to run the state and transfers to local administrations – costs over EUR 790 billion (or 51% of GDP) to taxpayers each year. Interest expenses alone cost EUR 85 billion. As an anecdote, did you know that the Italian Parliament cost taxpayers about EUR 1.65 bln in 2011, as much as the English, French and German ones together? Once accounting for sub-optimal GDP growth, the necessary resources to invest in productivity, social measures and new business initiatives remain scarce. At the same time, there is limited scope to reduce the high tax burden which affects families and impacts the ability of companies to become more competitive on international markets. In the World’s Economic Forum latest Global Competitiveness Report, Italy, the world’s 9th biggest economy, was moved down from number 42 to 49.

In parallel, doing business within the country remains problematic for companies and entrepreneurs:

- Justice – the World Bank’s “Doing Business” report for 2013 (figures here) shows that it takes an average 1,210 days to enforce a contract in Italy, more than twice the average of other OECD high-income countries. For those who prefer to see the glass half-full, days were 1,390 in 2004. But would you call this progress? Economic literature demonstrates that an inefficient judicial system and low quality legal institutions increase the cost of credit for companies because banks perceive, and therefore price in, more risk. It has also been shown to limit inward foreign direct investments (FDI) and dampen innovation. In the last three years of available data, FDI decreased from EUR 270 billion to EUR 247 billion (OECD 2011 figures, applying current EUR/USD exchange rates).

- A terrible customer – In October Eurostat published figures highlighting for the first time that the Italian government’s arrears to SMEs were in excess of EUR 67 billion (or 4.3% of GDP) at the end of 2011. More recent estimates by the Bank of Italy report EUR 91 billion (almost 6% of GDP). While EUR 40 billion have just been unblocked to finally repay some of the pending debt to Italian companies, the issue remains unresolved and will continue to affect weaker contractors, forcing defaults and increasing unemployment.

- Taxes – Italy has one of the highest corporate and personal tax regimes in the world, impacting both companies and private consumption. At the same time, Italian tax revenues (around EUR 470 billion in 2012) are not enough to keep up with the country’s excessive spending. The problem is that this tax pressure is un-even: too high for those who pay but nothing for the many that evade. Some estimates quantify tax evasion as being in the region of EUR 300 billion (or 15% of GDP in 2012), which is a sum equivalent to the GDP of Singapore, Greece or Denmark. Imagine the possibilities offered by unearthing that pocket of money? Reforms seriously targeting tax evasion would have a “fly-wheel” effect providing both an increase in state revenues and, hopefully, a subsequent decrease in the corporate and personal tax rate.

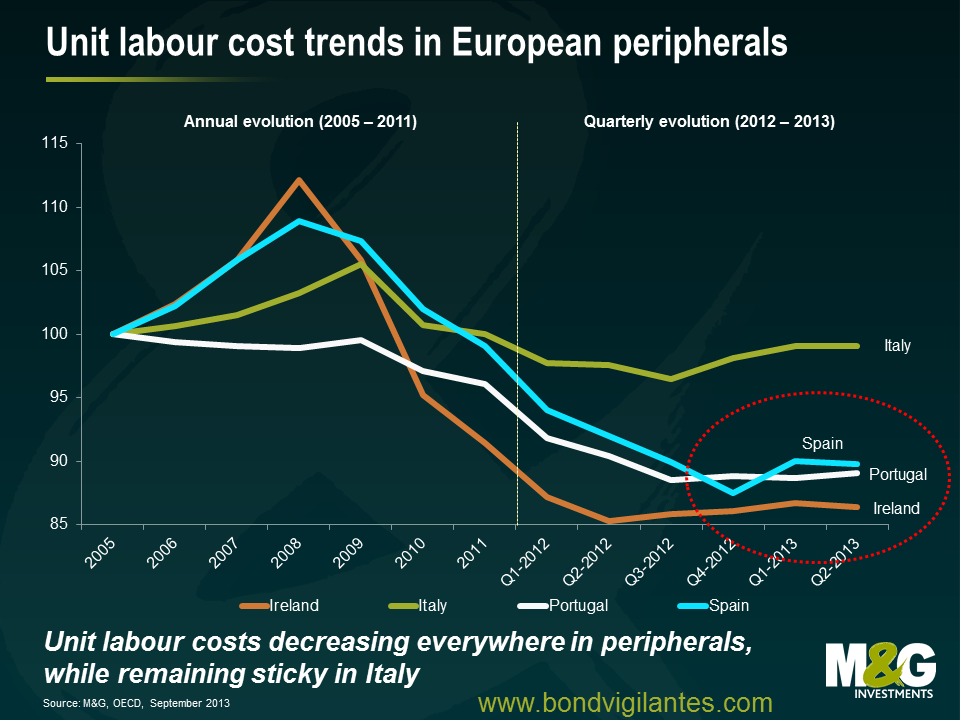

Additional ongoing economic issues in Italy are well known, from rising unemployment (latest reading in August reports a rate of 12.2%, with youth unemployment at 40.1%) to the excessive power of trade unions. Moreover, while labour costs have decreased in other European peripheral countries helping to make them more competitive, they have not done so in the “Bel Paese”.

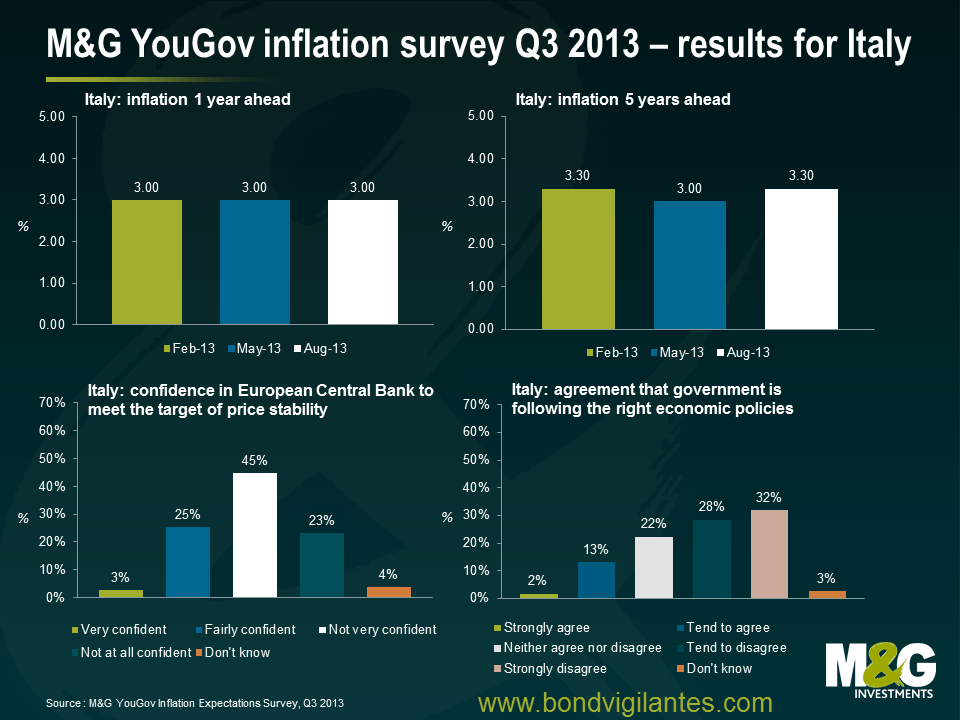

As a result of all of the above, Italian citizens – not surprisingly – have limited trust in institutions. The latest M&G YouGov Q3 2013 inflation report showed that the majority of respondents have little confidence in the government’s ability to follow the right economic policies. Results show a lack of trust in the government’s actions, but also a decreasing confidence in the central bank’s ability to maintain price stability over the medium term (ie inflation around 2%). For Italians, the European Central Bank is not doing much, suggesting that forward guidance measures may have been poorly received. Italians are also expecting a shift in inflation dynamics in the future, forecasting inflation up to 3% over 1 year and up to 3.3% over 5 years. This compares with the current inflation figure of 0.9% as of August 2013, reflecting the recession and a weak labour market.

3 – Now the good news: improving economic trends, size of private wealth and resiliency of Italian companies doing business abroad provide a different picture worth considering.

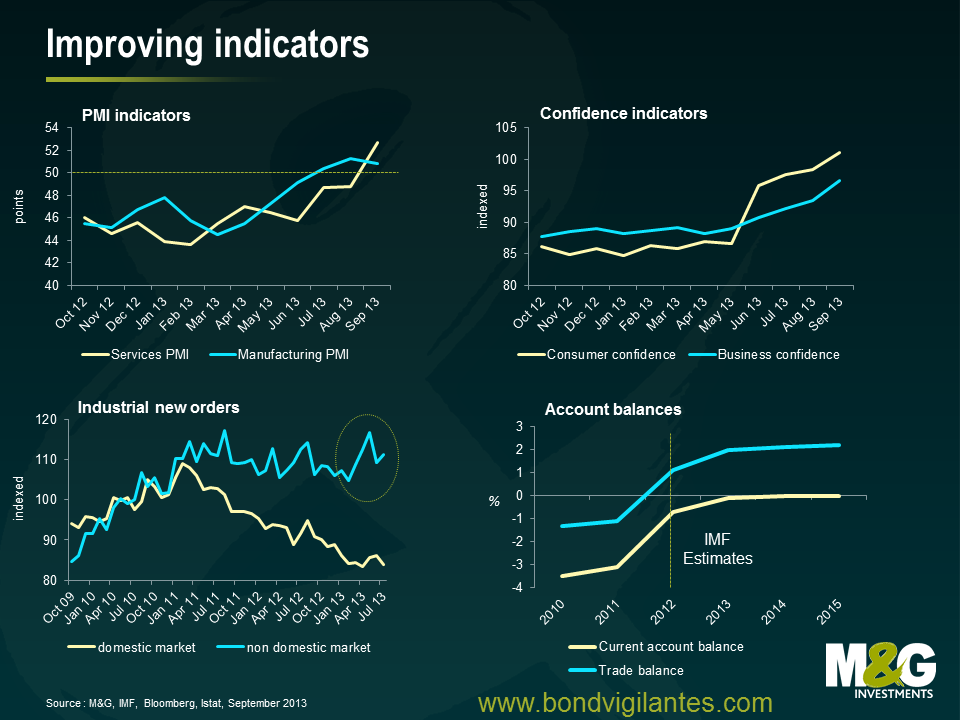

While the IMF expects Italy to come back to modest growth by 2014 with a GDP of only 0.7%, better news is that after nearly two years of recession Italy’s economy is showing signs of stabilising. Some indicators are finally improving, from PMI indices to confidence indicators and industrial new orders for the non-domestic market. The banking sector is progressing, even if we continue to be concerned. Let’s review some key developments.

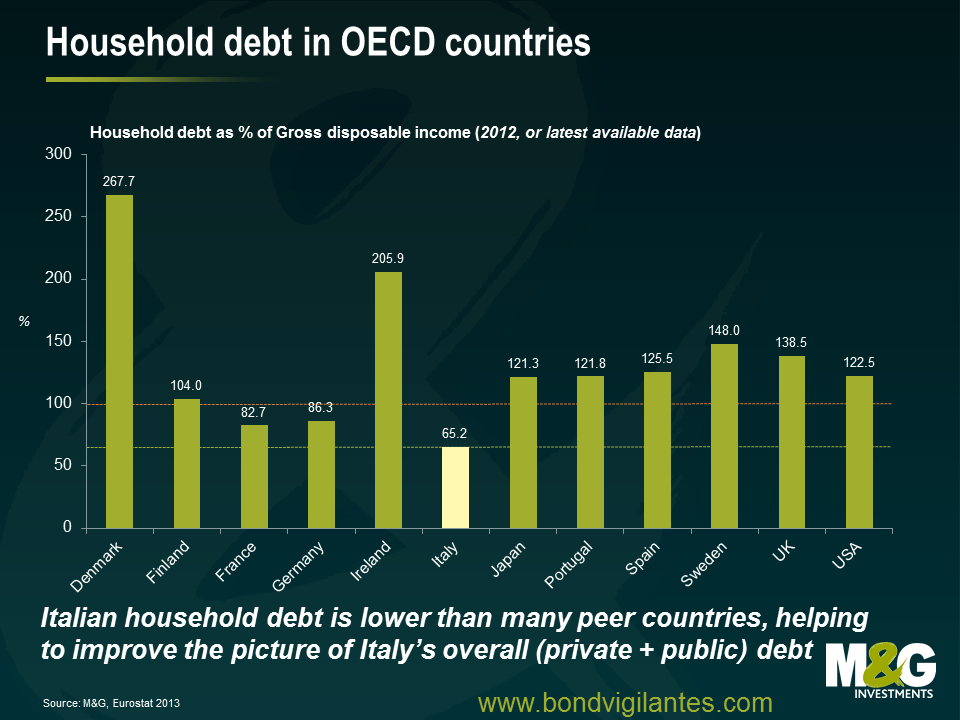

While unemployment, weak growth and other factors have eroded household income in the last few years – impacting both domestic demand (consumption) and savings rate – the existing stock of private wealth in the Italian peninsula (the sum of financial and non-financial assets minus liabilities) may offer a surprise. Wealth is one of the key components of the economic system, a source of finance for future consumption, for reducing vulnerability to shocks and to other unexpected developments, and for undertaking business and other economic activities. Italy is characterised by still having one of the highest levels of private wealth (gross household wealth) in Europe with a total of EUR 9 trillion assets, or 8.5 times the nominal disposable income (OECD 2013, based on 2011 figures). In the UK and France this figure is around 8 times, and only 7.6 times in Japan, 6.3 times in Germany and 5.2 times in the US. Such a high stock of savings is not a bad resource in times of economic downturn. These accumulated savings allow families to keep consuming (even if less than before) and, in many cases, prevent the long-term unemployed from a dramatic fall into poverty, thereby preventing social unrest and disorder. Moreover, given a low household indebtedness in the nation (even if on an increasing trend), the overall gross debt mix (public and private) provides a better picture than public debt on a stand-alone basis and looks broadly in line with the Euro area average around 300% of GDP.

On a different perspective, doing business outside Italy can be great for Italian companies. An IMF report issued last Friday highlights the strength of Italian exports in the face of a depressed global demand. Findings show that Italian trading firms continue to be solid, adaptable and resilient. At a macro level, with exports revamping and a depressed domestic economy keeping imports weak, the current account balance is improving. At micro-level, unlike many other European countries, Italy‘s tradeable sector continues to perform in a context of an established competition from low cost emerging markets. Agility, capacity for incremental innovation and a diversified range of high-quality, high-margin products have been highlighted as central factors allowing Italy to maintain its relative world position. The country remains the world‘s top ranked exporter in textiles, clothing and leather goods; it is ranked second in the world (behind Germany) for non-electronic machinery and manufacturing.

A number of Italian, non financial companies have very valuable brands recognised at a global level. Many are well managed businesses which continue to generate value, provide a source of talent and will continue to compete in international markets in the future. On the banking side, Italian banks on average have so far managed to overcome the shocks coming from a severe and prolonged recession at home and the crisis in Europe. Quoting a recent IMF report on Italian banks, the system has stabilised. Banks expanded domestic deposits and built additional capital buffers without significant state support. In addition, the impact of the sovereign debt crisis has been softened by the ECB intervention via LTRO and OMT announcement, shielding Italian banks from wholesale funding volatility. Capital buffers have strengthened in recent years and seem sufficient to absorb most of the losses in case of an adverse shock. In the team, we continue to believe that the system is not out of danger, though. Continuing weakness in the real economy and the link between the financial sector and the sovereign remain key risks. Weak profitability and deteriorating loan quality (the average non-performing loan ratio has nearly tripled to 14 per cent since 2007) are the most pressing vulnerabilities affecting Italian banks, while the coverage of non-performing loans by provisions and collateral remains lower than most other EU countries, a concern as the ECB is set to review banks’ asset quality in the first half of 2014. Moreover, while the decline of Italian sovereign yields from their peaks has eased these pressures, the crisis in Europe has not ended. Banks with large holdings of Italian government securities continue to be exposed to direct mark-to-market losses and higher funding costs should sovereign yields surge again.

We cannot ignore the ongoing concerns that the Italian economy and domestic companies continue to face. That said, it is important to continue to monitor progress towards a stronger and more competitive Italian growth model. Italian assets have rebounded strongly in 2013 (despite the recent political-induced wobble) and there are some good examples in credit markets of well diversified companies that are trading cheap, not because of fundamental problems, but reflecting the stress that Italian government bonds have come under in recent years. Valuation remains key for credit investors, and fundamental analysis will be crucial to picking winners in the peripheral markets.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

17 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox