I recently attended JP Morgan’s annual US high yield conference. It’s one of the best conferences around: well attended, and with more than 150 companies, panel discussions and specialist presentations. As such, the topics covered give a good flavour of the market’s latest thinking.

Unsurprisingly, many of the well-rehearsed arguments in favour of high yield resurfaced once again, with presentations focused on the following:

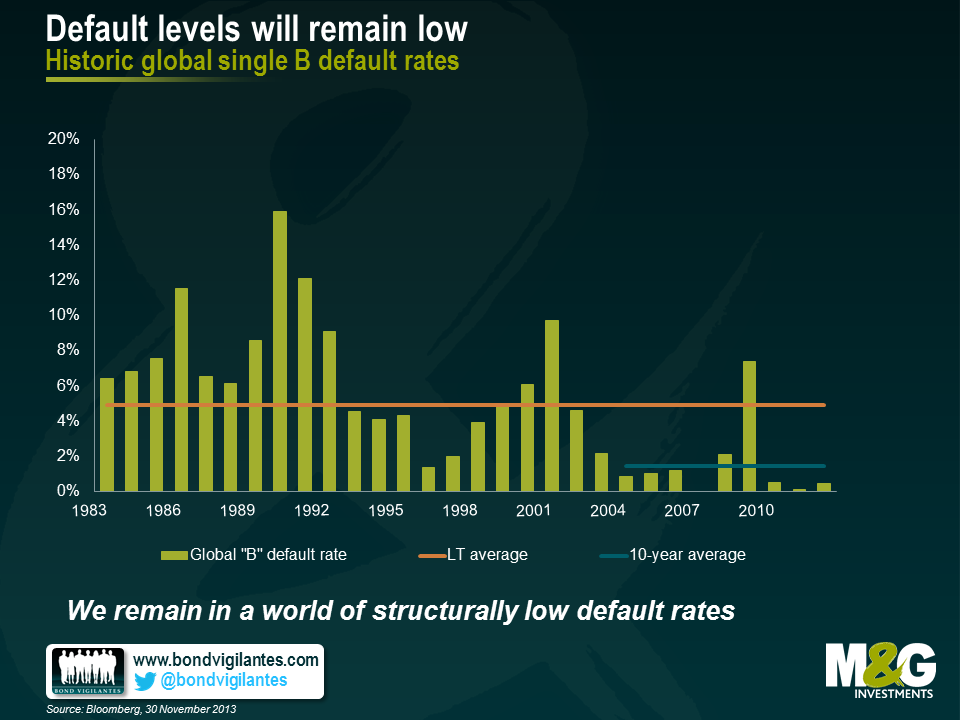

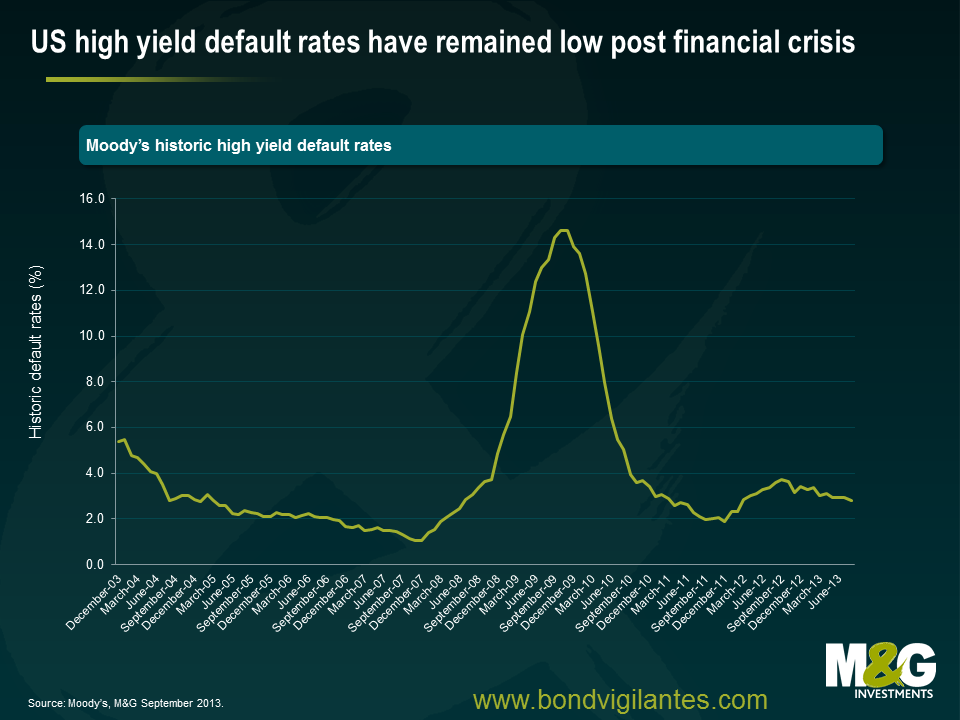

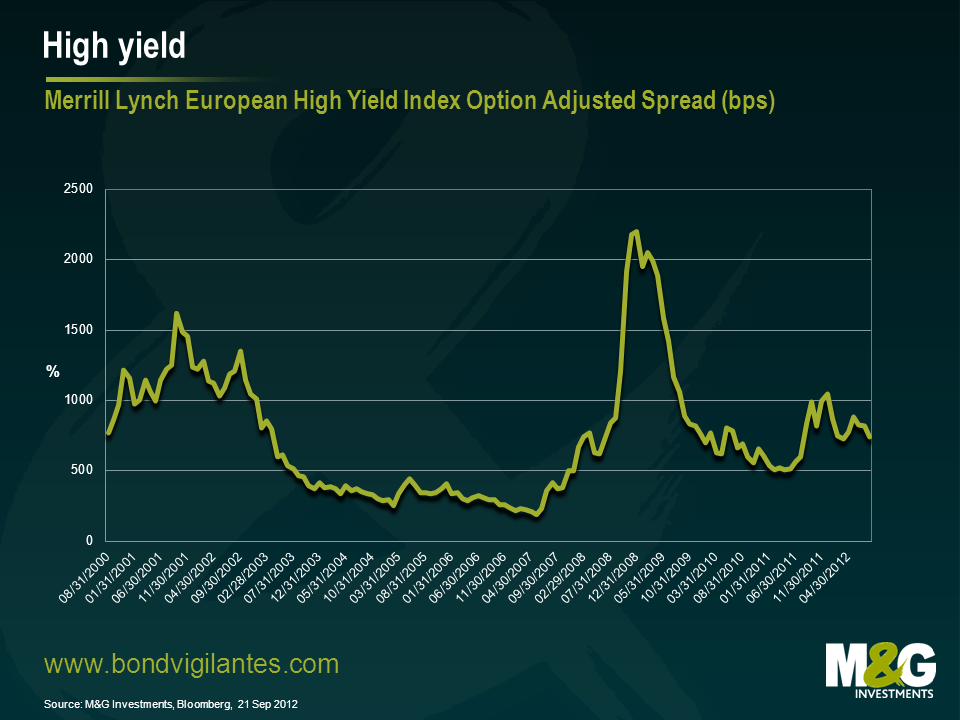

- The structurally low default rate (see chart below), largely a function of accommodative central bank policy, limited refinancing risk and growing investor maturity, with spreads over-compensating as a result.

- Projections that US high yield will outperform other fixed interest asset classes in 2014, returning 5%-6% (leveraged loans likely to deliver 4.5%).

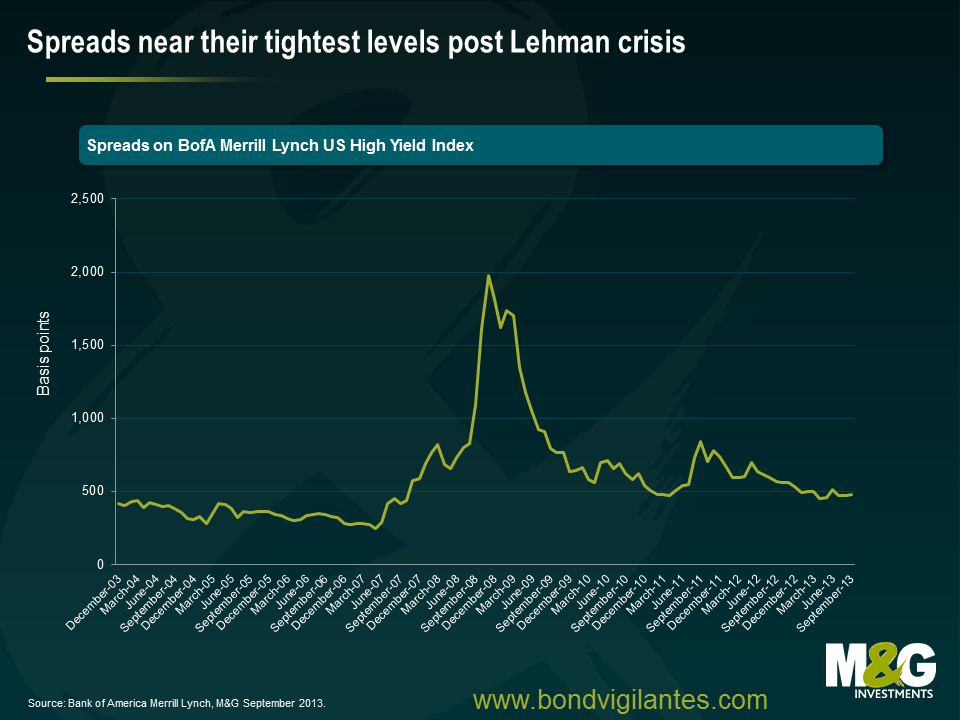

- Room for spreads to tighten further given that they remain over 100+ bps back of the lows in 2007. Currently 378bps vs 241bps in May 2007.

- How refinancing, rather than new borrowing, is driving the majority of issuance in the US. Refinancing accounted for 56% of issuance in 2013, though down from 60% in 2012.

- The need for income in a low interest rate world is providing a strong technical support, evidenced by $2bn+ of mutual fund inflows into the US high yield market year to date. Significant oversubscription for the vast majority of new issues has also been a notable feature of the market for some time now.

- The short duration nature of the asset class – particularly attractive in an environment of potentially rising rates. Modified duration for US and European high yield is 3.5 years and 3 years respectively. This compares to 6.5 and 4.5 years for the investment grade equivalents.

Now these are all relevant arguments in favour of the asset class, and indeed I believe that US high yield will likely be one of fixed income’s winners in 2014. What did surprise me, though, was the almost total absence of discussion around some of the headwinds that it faces.

For example, presentations seemed to gloss over the fact that much of the good news, from the perspective of default rates at least, has arguably already been priced in. The market is unlikely to be surprised by another year of sub-2% defaults, rather the risk lies in an outcome that sees a higher default rate than anticipated by the consensus, even if that is difficult to envisage right now.

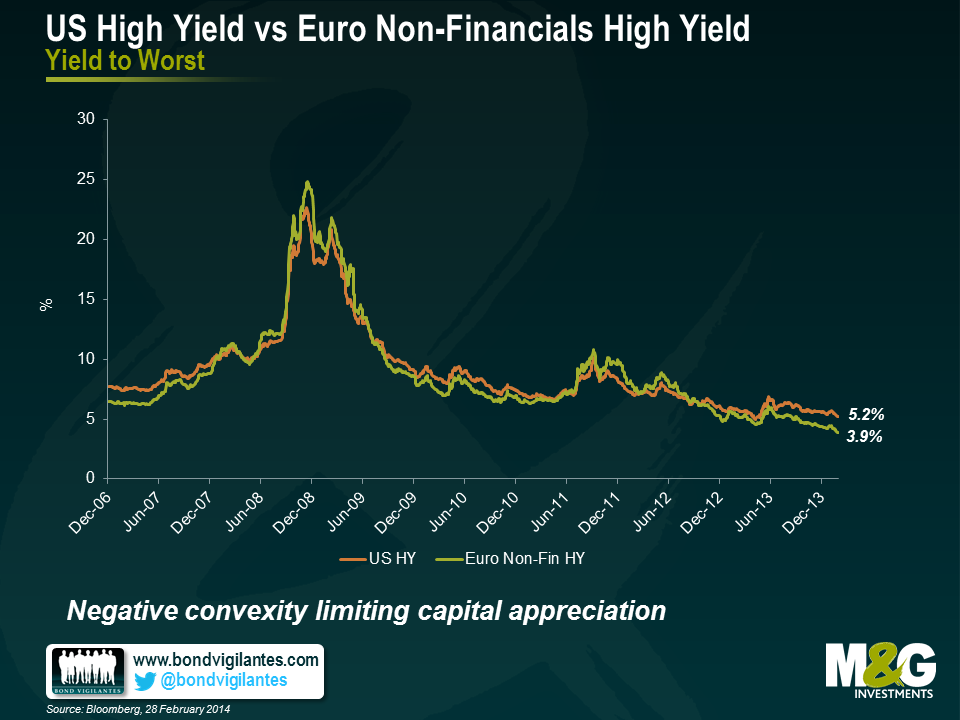

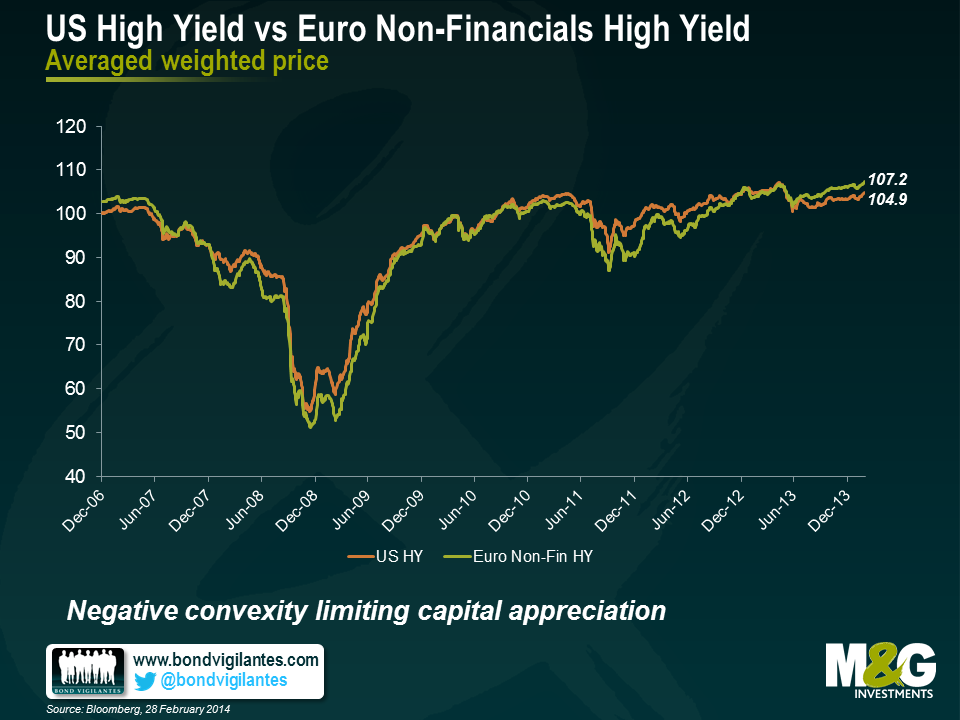

Other challenges are presented by liquidity (while this has improved since the immediate aftermath of the credit crunch, investment banks are still reluctant to offer liquidity given the high capital charges they face and the low yields currently on offer); by the lack of leverage available to end investors compared to 2006-7, when banks had the ability, strength and desire to lend to those investors on margin; and by the increasing negative convexity the market faces at the moment.

With US high yield paper already trading at an average price of 105 and as high as 107 in Europe (see chart above), the threat of bonds being called will act as a cap on further capital appreciation. And, of course, the flip side of these high prices is low all-in yields. With these standing around 3.8% on the European non-financial high yield index and 5.2% on the US high yield index, investors can only question how much lower they can go.

Perhaps in this environment, with inflation ticking along comfortably below 2%, investors should accept that a nominal return of 5-6% looks decent. That said, returns this year are likely to be driven by income rather than capital appreciation, and may well look skinny versus previous years. As I said before, I’m still constructive on high yield, but after the stellar returns in the past few years, we must be careful to avoid being blinkered.

Last week saw year-on-year core inflation in the euro area fall from just over 1% in September to a two year low of 0.7% in October (see chart). Such a level is entirely inconsistent with the ECB’s definition of price stability as inflation “below but close to 2%”, and will likely be met with a downward revision to medium term inflation prospects and with it an ECB rate cut later this year.

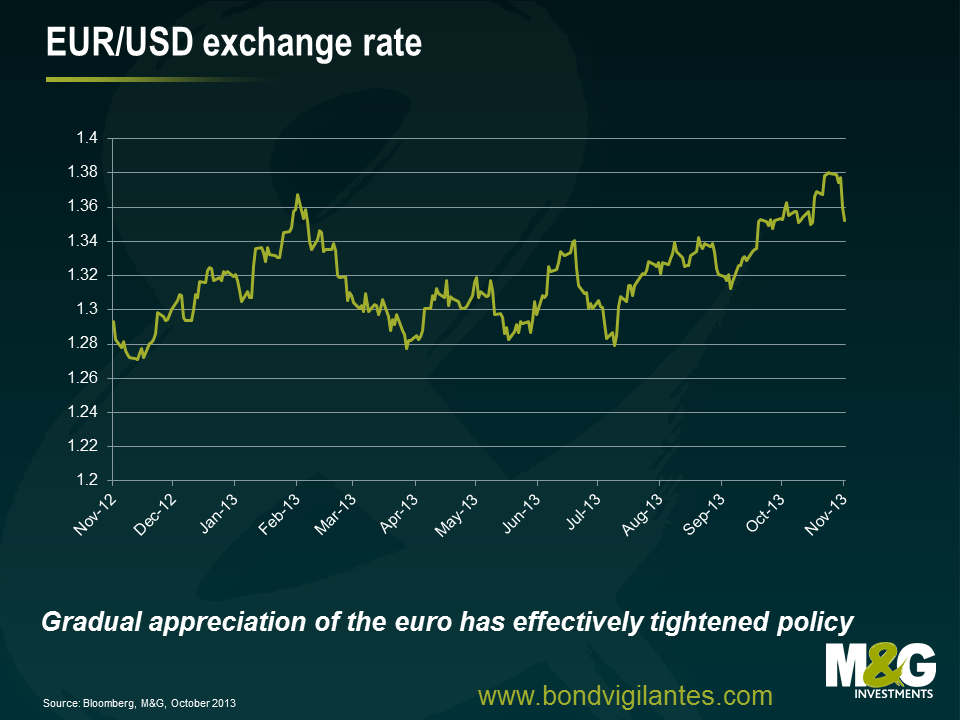

The ECB will no doubt have monitored the recent steady appreciation of the euro (see chart), which has effectively acted as a tightening of policy and will likely have a disproportionately negative effect on the periphery. Coupled with the latest inflation data, the strengthening of the euro will no doubt increase calls from the doves on the Governing Council (who should be acutely aware of the rising risks of a Japanese-style deflationary trap) to run a more stimulative policy.

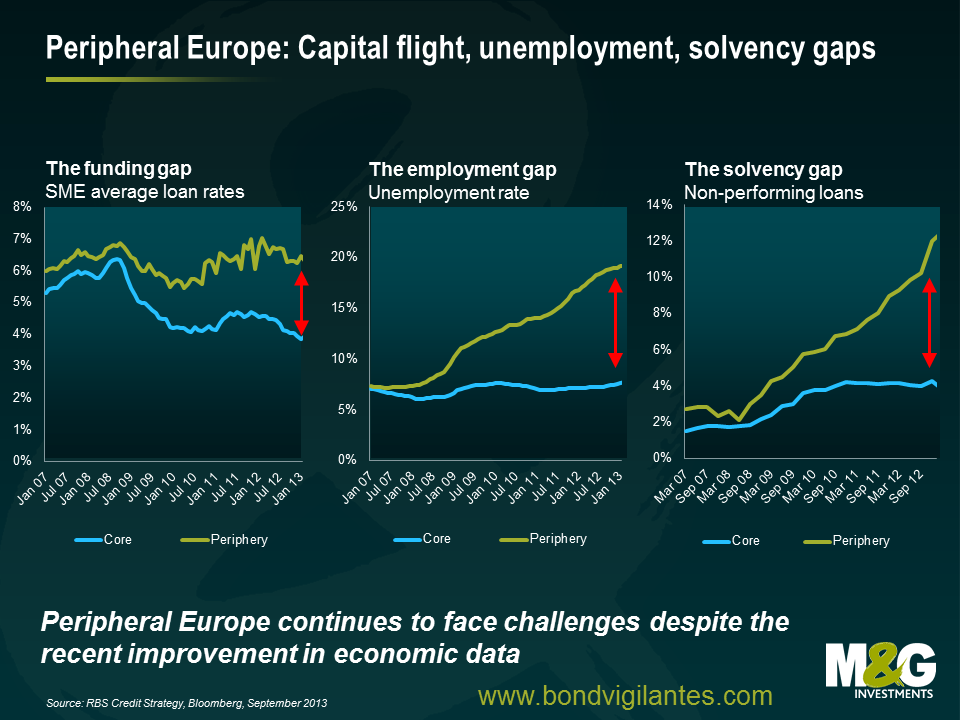

With little evidence of upward pressure on German wages, the internal devaluation required within the eurozone to facilitate a more competitive and balanced economic area has also been dealt a blow. Richard recently noted an improvement in euro area funding costs, and with it a stabilisation of broader economic data. However, this is from a very low base and the challenges that Europe continues to face should not be underestimated. Both unemployment and SME funding costs remain stubbornly high in the periphery and non-performing loans continue to move in the wrong direction (see chart). The ECB understandably wants to maintain pressure on politicians to deliver on structural reforms, and no doubt some harbour fears of leaving fewer policy tools at their disposal once they cut rates towards zero, but the risks of medium term inflation expectations becoming unanchored to the downside should be a wakeup call and a call to action!

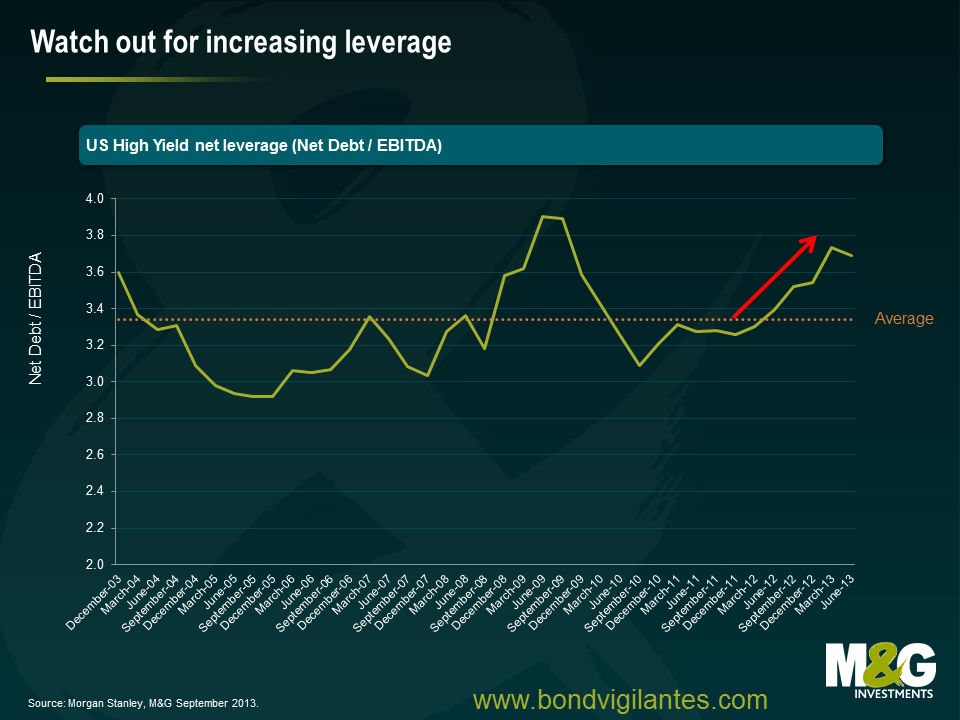

The high yield market rightly pays a good deal of attention to leverage trends (the relationship between debt and earnings). The larger the quantum of debt a business carries relative to its earnings, the greater the risk. Other metrics are arguably as important, though it is the leverage metric that consistently garners the lion’s share of attention. With spreads near the post Lehman tights, it is unquestionably concerning to see a trend of rising leverage as earnings plateau and companies generally take on more debt.

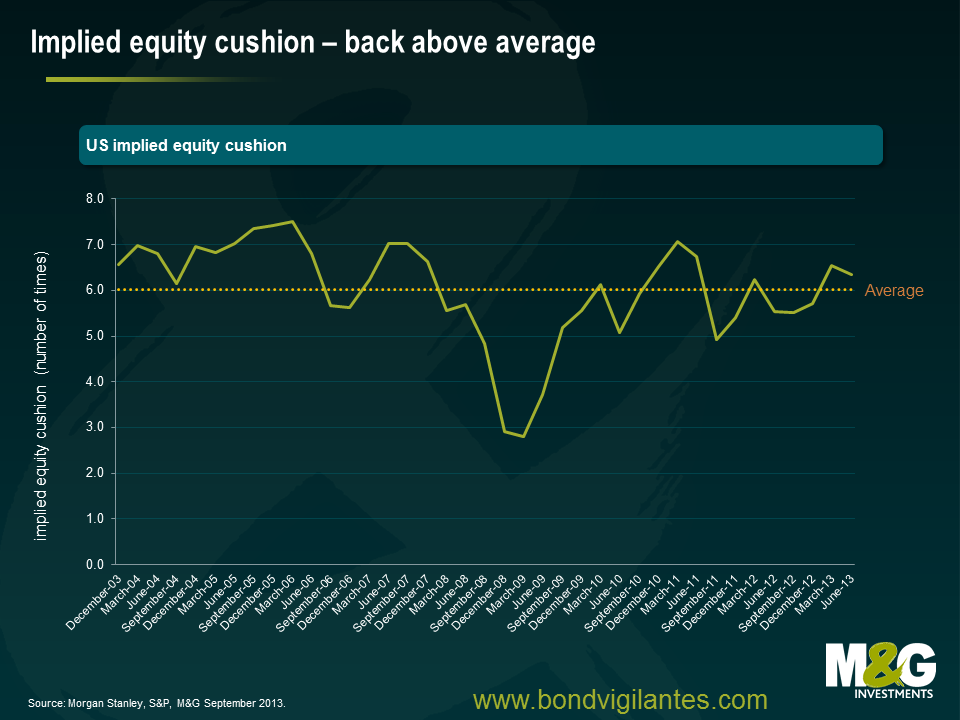

The very same central bank policies that have kept bond yields low and encouraged high yield companies to take on more debt have also helped to support higher equity prices. As money has flooded into the asset class, the market has not surprisingly re-rated upwards. What this has meant for high yield investors is that one measure of the ‘margin of safety’, or an equity cushion has, at least temporarily, been increased. The chart below shows the implied equity cushion by subtracting the average level of US high yield leverage from the S&P Mid Cap trailing 12 month enterprise multiple. The higher the implied cushion the better. So for example with stock markets at the lows in early 2009, the implied equity cushion fell to a mere two turns, but has since recovered to a far more healthy and above average six.

Many will no doubt point out that an implied cushion is exactly that- implied. And the argument is clearly a pro- cyclical one that relies on an imperfect comparison. We’d concur with that and emphasise the fact that there can be no substitute for thorough credit analysis. We will always prefer to invest in appropriate financial leverage, strong interest coverage and free cash flow generation over equity implied multiples. The former gives a business flexibility and exposes it less to market vagaries.

Yet there is no getting away from the fact that central bank policy has, and can still yet, come to the rescue of even some of most levered high yield companies. In hindsight, few of us would have predicted the surprisingly low level of defaults we’ve witnessed through this cycle. And whilst IPOs of high yield companies has been a fairly rare thing over the last few years, higher equity multiples, an on-going return of animal spirits and a desire/need to put money to work may yet alter that trend.

Just when you thought the Fed had well and truly killed the carry trade, a surprisingly dovish Mario Draghi reminded markets yesterday that Europe remains a very different place from the US. Having previously argued that the ECB never pre commits to forward guidance, yesterday marks something of a volte-face. ‘The Governing Council expects the key ECB interest rates to remain at present or lower levels for an extended period of time.’ The willingness to offer guidance brings the ECB closer to its UK and US peers, the latter having been in the guidance camp for some time. This firmly reinforces our view that the ECB retains an accommodative stance and an easing bias.

The willingness to offer forward guidance to the market no doubt came after some long and hard introspection within the Governing Council. So why the change ? Firstly, the ECB is worried that it may miss its primary target of maintaining inflation at or close to 2% over the medium term. Secondly, Draghi indicated an increasing concern that the real economy continues to demonstrate ‘broad based’ weakness, and finally, as has been the case for some time, the Council worries that the Eurozone continues to labour with subdued monetary dynamics. This sounds increasingly like Fed talk of recent years.

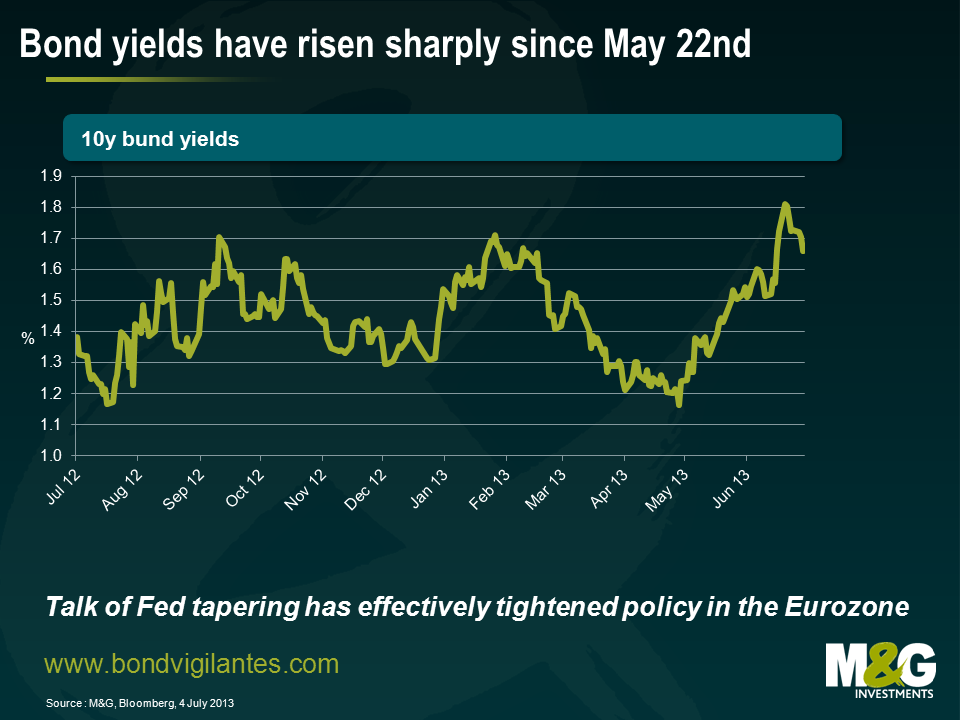

Draghi also expressed his concern yesterday during his Q&A at the effective tightening of monetary conditions via higher government bond yields (see chart) since the Fed’s tapering discussions. Frankly the last thing the Eurozone needs at this stage in its nascent recovery is higher borrowing costs.

Draghi in communicating that the next likely move will be an easing of policy has attempted to talk bond yields down. European risk assets appear to have taken his comments positively but the bond market remains sceptical. At the time of writing only short to medium dated bonds are trading at lower yields.

In conjunction with revising down its 2013 Italian GDP forecast from -1.5% to -1.8%, the IMF has publicly urged the ECB to embark upon direct asset purchases. Is this a likely near term response ? For now those calls will likely fall on deaf ears especially with German elections later this year. The ECB clearly believes that its next move would be to cut rates further in response to a weaker outlook. Buying time seems to be the current approach.

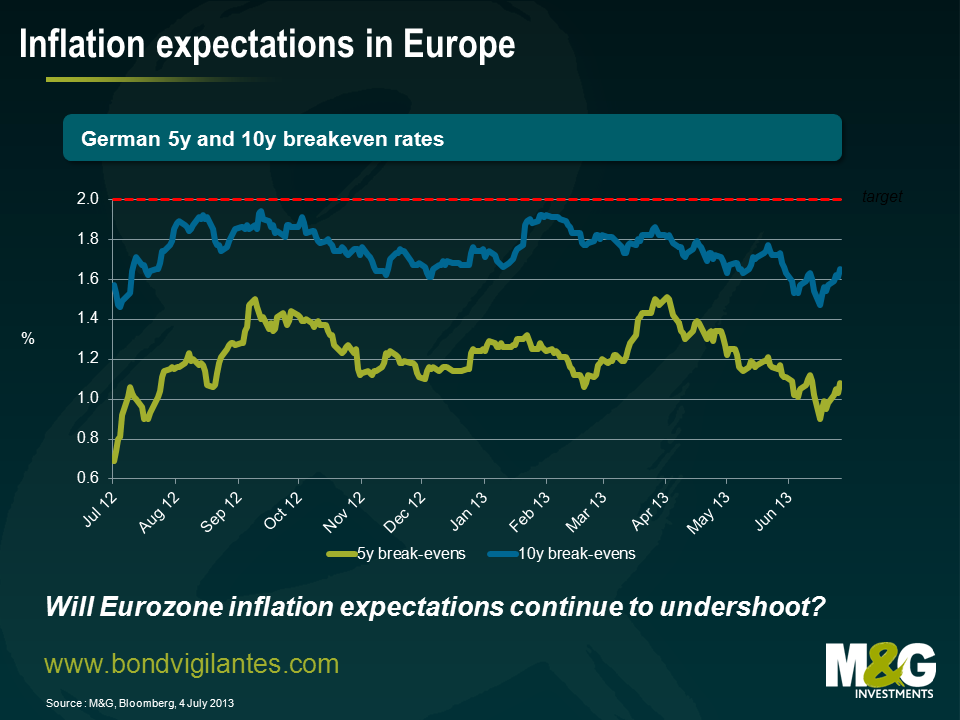

However, should Eurozone inflation expectations continue to undershoot (the market is currently pricing 1.36% and 1.66% over the next 5 & 10 years, see chart) and economic performance remain downright lacklustre across Europe, then the ECB will have to think very carefully about what impact it can expect from a ‘traditional’ monetary response. QE may be some way off, and would no doubt see massive objections from Berlin, but in the same way that the ECB never pre commits, maybe just maybe, QE will be on the table sooner than the market is currently anticipating.

After years of inactivity, the combination of strong corporate balance sheets and cheap funding has sparked demand for takeover deals. The largest and highest profile deal this year has been the acquisition of H.J.Heinz by 3G Capital and Berkshire Hathaway. It is exactly the type of business that Berkshire Hathaway’s Chairman and CEO Warren Buffett typically goes for: profitable growth; a very recognisable brand; and years of emerging market growth forecast in the future.

Berkshire Hathaway and 3G Capital are buying Heinz for $72.50 per share, a 19 percent premium to the company’s previous record high stock price at the time the deal was announced in mid-February. Including debt assumption, the transaction was valued at $28 billion. Berkshire and 3G will each put up $4.4bn in equity for the deal along with $12.2bn in debt financing. Berkshire is also buying $8bn of preferred equity that pays 9%.

Let’s not beat around the bush. It’s a great company. The business has seen thirty one consecutive quarters of organic growth, stable EBITDA margins, owns a number of globally recognised brands and should be well positioned for future emerging market led growth. Despite this, some are questioning whether Buffett is overpaying for Heinz. So is the price of the deal justified?

The answer, at least in part, lies with cost of debt. The pro-forma capital structure (per the offering memorandum) looks like this:

| PF Capital Structure | Sources ($m) | Net Debt/PF EBITDA |

| Cash | -1,250 | |

| 1st Lien | 10,500 | 3.87 x |

| 2nd Lien | 2,100 | 4.75 x |

| Rollover Notes | 868 | 5.11 x |

| Total debt | 12,218 | 5.11 x |

| Preferred Equity | 8,000 | 8.46 x |

| Common Equity | 8,240 | |

| Total | 28,458 |

Current price talk on the first lien debt sits at $ Libor + 2.75% (floored at 1%) with the second lien at 4.5%. If this is finalised, the company will see an approximate blended interest cost of 3.9% on its new debt securities. Prior to the transaction, Heinz was rated as a solid investment grade business attracting a Baa2/BBB+ rating. Assuming the deal goes through, its new second lien notes are expected to be rated B1/BB-, some five notches lower than Heinz’s current rating, reflecting the much higher financial leverage and structural subordination.

It’s worth noting that through last year Heinz’s 6.25% 2030 bonds traded in a range of 4–5%, despite the much higher rating and lower financial leverage at the time; albeit some term premium is warranted given the longer dated nature of the debt. The bonds have since sold off in recognition of the greater risk – as things stand they will remain in place.

Now let’s compare the price action of the proposed debt financing to the preferred equity to be owned by Berkshire Hathaway. Whilst the paper is structurally subordinate to all other debt, it still sits ahead of some $8,240bn of common equity and attracts a cash coupon (which can be deferred) of 9% vs the 3.9% weighted average above. It’s also worth bearing in mind that the transaction has been structured to encourage the preferred equity to be retired, at least in part, ahead of both the first and second lien debt, potentially leaving bondholders with significantly less subordination than at day one. I’d argue that this is by far the most attractive (quasi) debt to invest in within the structure, though that is hardly surprising given that unlike Buffett, few of us can write a cheque of this magnitude.

As animal spirits return and the leveraged finance community falls over itself to lend to well known companies, the likely winners in the space will be the private equity community. Whilst we are nowhere near the levels of the great private equity binge of 2004-07, the value of takeovers in 2013 is already running well ahead of 2012. After years of corporate deleveraging, we may now be entering into a period of increased M&A activity. Company managers may find that if they aren’t willing to start leveraging up given the environment of extremely low borrowing costs, then investors like Buffett will do it for them.

The Heinz deal has been another recent shot across the bows of the bond market. Rising leverage has a longer term implication for credit markets, in that it is bad for credit quality. Bigger and bigger companies are clearly in play and this is something we will be keeping a very close eye on.

Depositors in Cypriot banks awoke on Saturday morning to learn a harsh lesson. A guarantee is only as strong as your counterparty. With the Cypriot banking system requiring €10-12 billion of bailout funds – some 60% of GDP – the government has been forced to accept burden sharing with depositors. Depositors who went to bed Friday night believing their savings were safe awoke Saturday to find that it has been proposed that those with deposits below €100k in the bank will be “taxed” at 6.75%; those with deposits above €100k will be “taxed” at 9.9%, contributing approximately €6bn to the bank bailout in total. This is regardless of supposed depositor insurance schemes. Depositors will receive equity in their respective banks by way of compensation and potentially bonds entitling those who leave their money in the banks for 2 years to a share of Cyprus’ future gas revenues. The remaining €4-6 billion will likely come from the Troika.

If press reports are to be believed this was a ‘take it or leave it offer’ from the Troika with German and Finnish finance ministers unwilling to go to their respective parliaments without depositor burden sharing. This highlights the very real current challenges of domestic politics within the European Economic and Monetary Union and raises further issues.

Firstly, there are significant political challenges to be faced. Domestic opposition to this deal is likely to be significant, not least as it will be seen to be disproportionately harsh on domestic savers – who had believed their deposits were protected up to €100k, and favourable to wealthy non-Cypriot depositors who reportedly hold huge sums offshore in the banks. It can be argued that those with over €100k in deposits with the banks should bear the brunt of any proposed bail-in. With a small parliamentary majority, the Cypriot government may struggle to pass the necessary legislation. Approval will also need to be sought from Eurozone member states.

Secondly, alongside the recent expropriation of junior bond holders at SNS Reaal the attitude towards tax funded bailouts appears to be hardening. Whilst this crisis has already witnessed both equity and debt written down, the rubicon of depositor burden sharing has now been crossed. Precedent now exists for this approach over the socialisation of losses across the Eurozone as a whole. Whilst the Troika will endeavour to play its significance down, unintended consequences may still materialise.

Thirdly, the Cypriot situation serves as a reminder of the current fragmented approach of depositor guarantee schemes across Europe. Depositor guarantees are only as strong as the sovereigns providing them. In the case of Cyprus with a banking system seven times the size of its economy, clearly those guarantees were worth very little. With depositor rates currently paying very little across Europe it is unlikely to take much to prompt a change in investor behaviour.

Fourthly, it raises real questions about depositor preference. With only circa €2bn of Cypriot bank debt outstanding, policymakers have judged this too small in and of itself to recapitalise the banking system. That may be true. However by favouring senior debt over depositors it does beg the question whether the individual on the street is in theory better off owning higher yielding bank debt than depositing cash.

Fifthly, the ECB has apparently threatened that if the measures are not agreed, then it would withdraw European Liquidity Assistance (ELA) funding for Laiki Bank, Cyprus’ second largest bank, leaving the Cypriot sovereign with the bill for the entire banking sector and having to pay out on deposit insurance in full. This highlights the extent to which a number of banks in Europe remain reliant on ECB funding, and that if that funding is withdrawn then their collapse is inevitable.

Finally, we have yet another example of a country being forced to face a stark choice between ceding sovereignty to Brussels or facing financial ruin. The Eurozone project continues to ask a great deal of its citizens. Bailouts don’t – and won’t – come cheap.

The Cyprus deal will be in the headlines for the next few days. We can’t help but think that the markets will be listening to Cypress Hill – Insane In The Brain for the next week or so. Maybe the Troika should too.

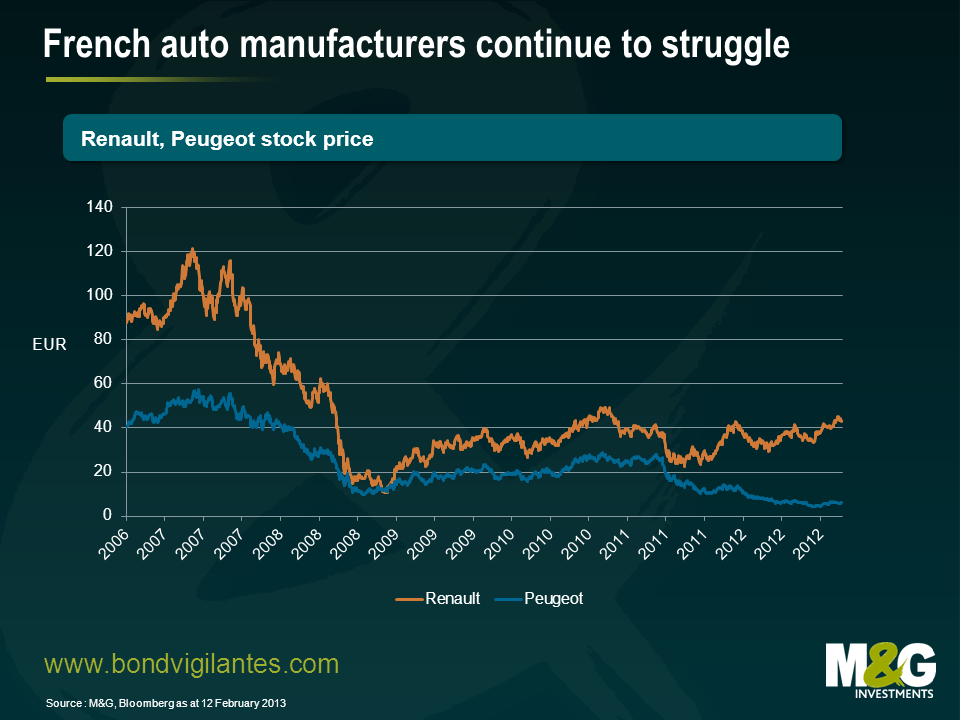

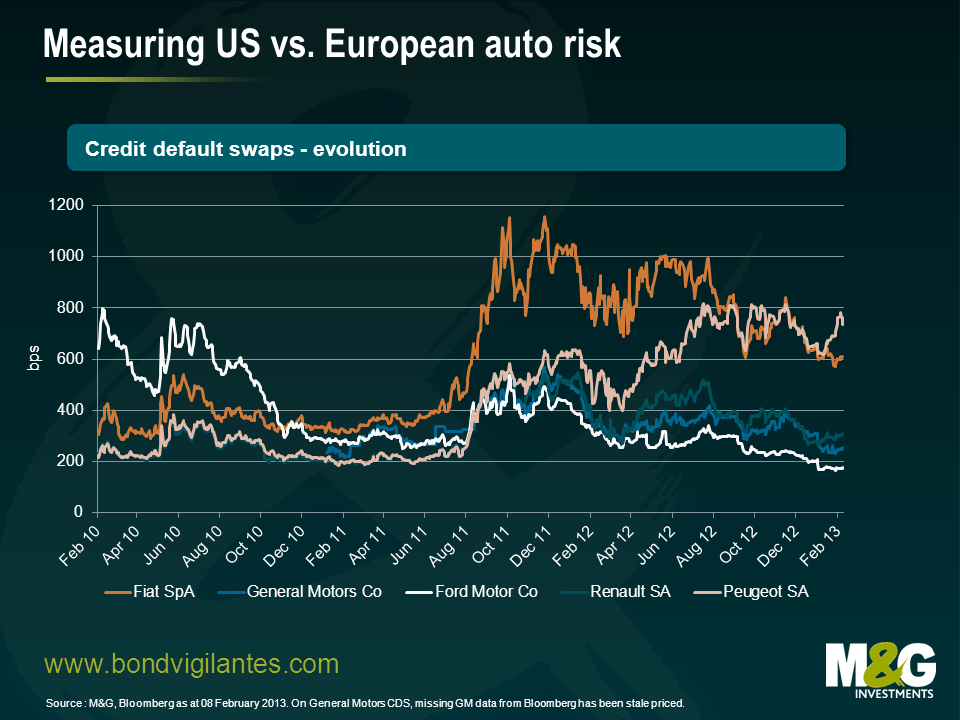

French auto manufacturers Peugeot and Renault report full year 2012 earnings this week. If Peugeot SA’s write down announced on Friday is anything to go by – when it took a €4.7bn non-cash charge – the outlook for the company and indeed other European focussed auto manufacturers continues to be a bleak one. European market conditions have been described by S&P as ‘dire’. Overcapacity and general economic uncertainty have resulted in utilisation rates below break-even profitability for a number of plants. Cash continues to be burnt and unsurprisingly, share prices don’t make for pleasant reading.

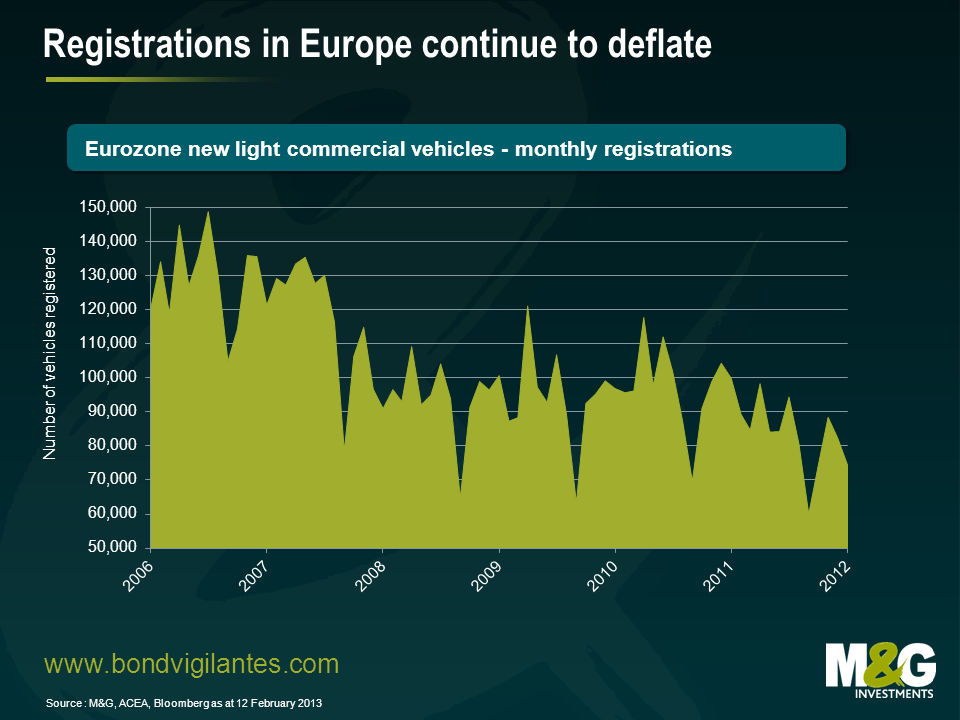

The need for an overhaul of the likes of Peugeot, Fiat and Renault remains acute. European light vehicle registrations are headed for a fifth consecutive year of declines (see chart below), Italian and Spanish registrations are at nearly half their pre-crisis levels, profit margins on compact vehicles are slim and Peugeot, Fiat and Renault are losing market share to investment grade rated manufacturers like BMW, VW and Daimler.

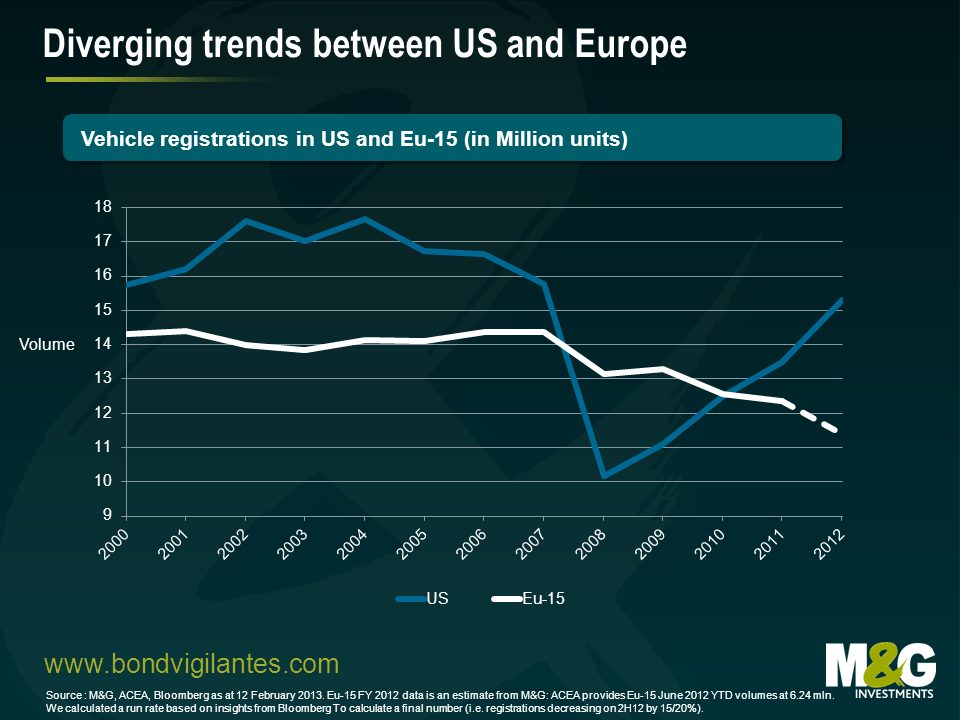

Struggling under a mountain of debt, Peugeot, Fiat and Renault find themselves in a non-too dissimilar position to that of the US auto manufacturers back in 2008/2009. Several years ago GM, Ford and Chrysler were able to successfully restructure, both inside and outside of bankruptcy, allowing them to close capacity, reduce over-indebtedness, renegotiate onerous union contracts and subsequently return to profitability even at levels of production significantly below those pre-crisis. That experience remains in stark contrast to European OEMs (Original Equipment Manufacturers) who continue to labour under many of those same pressures whilst facing ongoing weak domestic demand.

Management continues to struggle to right-size their businesses some 5+ years into the financial crisis in the face of strong political pressure and a determination to avoid job losses. Ironically, the very interference that has hampered change in Europe has now led to Peugeot having to rely on French state support. But these choices cannot be put off into perpetuity and unwelcome decisions are inevitable. Until that point in time, losses will continue to mount, cash will be burnt and creditors will likely favour US over European OEM risk.

As investors, the majority of our time is spent pricing risk with an increasing amount of that spent trying to value optionality. We’ve always had to price the optionality inherent in owning certain bonds. For instance what’s the likelihood of a call option sold to a bond issuer being exercised? What’s the likelihood of an early refinancing, or perhaps a change of control? These and other options are both risks and opportunities that credit investors will regularly have to consider and reconsider.

Some of the more recent options that credit investors have been forced to consider are those embedded within contingent capital notes or CoCos. These aren’t entirely new securities with Lloyds having exchanged bonds for CoCos back in 2009. Simplistically these ‘first generation’ CoCos are designed to behave like a traditional bond until a pre-defined trigger is breached. When triggered, first generation CoCo holders are forcibly converted into equity at pre-determined pricing, aiding the bank with its recapitalisation efforts. These instruments have found favour with the regulator not least because traditional subordinate capital instruments proved themselves almost entirely ineffective in providing loss absorbing capital.

However, since the issuance in 2009 the market has moved on somewhat and a new breed of CoCo has since emerged. Many of these newer instruments (see chart above) are designed to be written off entirely in the event of a trigger without the conversion into equity discussed above. This optionality has two obvious implications. Firstly, given that investors are written down to zero without equity conversion, any prospect of participating in a future recovery becomes null and void. Secondly (with the caveat that the quantum of issuance remains small for now), the prospect of a bond essentially performing the role of a non dilutive emergency rights issue has to be positive for all other stakeholders in the bank, not least common shareholders. And don’t forget that the majority of these instruments will see their coupons paid before tax, further enhancing the relative value of said issuance.

Selling all this optionality does have its price, as do most things in life, but the current exuberance in credit markets may yet see CoCo investors fail to exact an adequate premium.

Staying with the Bon Jovi theme, ‘Ugly’ was a track released by Jon Bon Jovi on his second solo album in 1998. It isn’t well known, or any good for that matter, but it does aptly describe the price action of Spanish and Italian corporate paper of late.

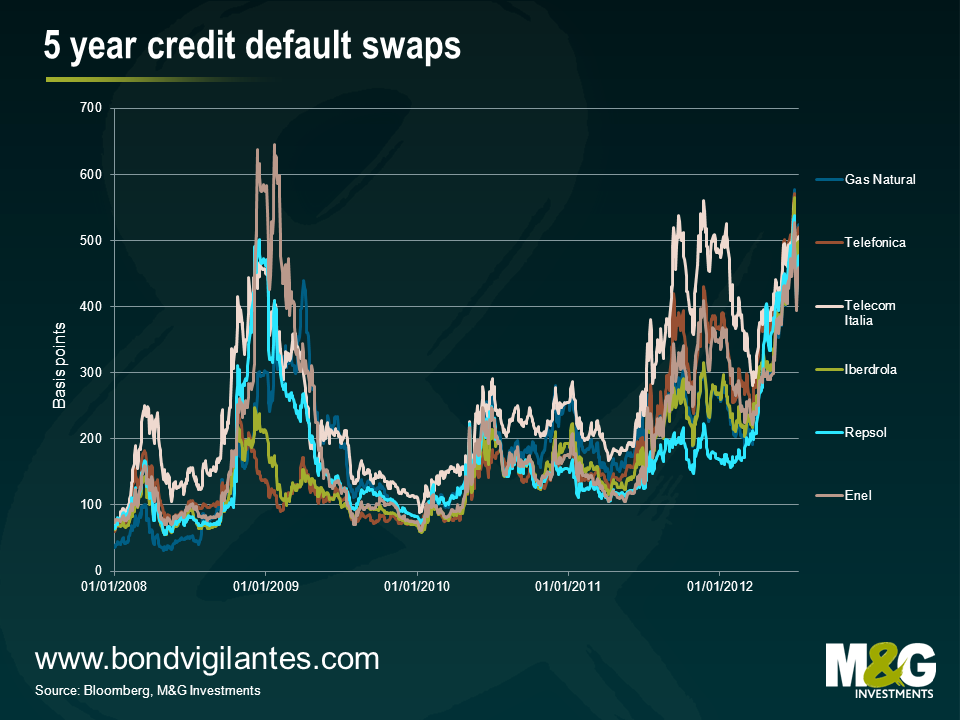

Plenty of attention has been paid to the yield on Spanish and Italian govies – currently around 7% and 6% for 10-year bonds – but their bellwether non-financial corporate issuers have also seen their yields come under significant pressure. 5-year CDS levels for the likes of Iberdrola, Gas Natural, Repsol and Enel are trading near their all-time wides at 500, 525, 475 and 455 bps respectively. And it isn’t just the utilities that have come under pressure: Telefonica and Telecom Italia have also seen their risk premia balloon to over 500bps. (see chart 1)

Whilst the aforementioned companies are still rated investment grade – some by many notches – they are actually trading wide of the Merrill Lynch BB Euro High Yield Non Financial Index (current asset swap of +440). Put another way, the market does not believe that these businesses represent investment grade risks.

Such a view isn’t without logic. The current ratings for the largest Spanish and Italian non-financial issuers (see chart 2) suggest that the market is right to be nervous. On average, the four largest Spanish issuers are only two notches above high yield status; for Italy’s five largest issuers it’s about three notches. That may seem like a fair bit of runway until you think about the pace of downgrades suffered by their sovereigns of late. Keep in mind that as late as July 2011 Moody’s rated Spain at Aa2, seven notches higher than its current Baa3 rating. Italy has also seen its rating cut a full four notches between June 2011 and Feb 2012 by the agency. And S&P hasn’t been much kinder, slashing Spain’s rating from AA- to BBB+ in under a year and reducing Italy from A+ to BBB+.

Both Spanish and Italian corporates saw negative rating actions as a consequence of those sovereign downgrades. Moody’s allows non-financial corporates a maximum two-notch rating uplift versus the sovereign, whereas S&P permits a maximum of six in extremis, with a couple of notches uplift far more common. The impact on Greek and Portuguese corporate bonds – such as EDP, OTE and Portugal Telecom – after their sovereigns lost their investment grade status serves to reinforce the potentially significant relationship between sovereign and corporate credit ratings.

So, in a hypothetical mass downgrade scenario what quantum of debt could be downgraded to high yield? If all Italian and Spanish non-financial paper were eventually to lose its investment grade status, we calculate that €47bn nominal of Spanish paper and €59bn nominal of Italian paper could fall into high yield territory. That would be a massive €106bn worth of paper – or 80% of the existing non-financial Euro High Yield index – heading into the high yield market. That’s a lot of paper for it to swallow.

Of course, the actual amount of debt that would end up for sale is difficult to quantify. This would depend, among other things, on index rules and investors’ willingness and ability to hold high yield bonds. However, it seems reasonable to assume that over the coming months and even years a significant amount of paper will need to find a new home. Yields may well have to climb further, potentially a lot further, before traditional high yield investors see value in these names.

This week saw Deutsche Bank publish their 2012 Default Study, aptly subtitled ‘5yrs of crisis – The default bark far worse than the bite..’ The annual piece is particularly interesting, especially because the market now has five years of data since the onset of the great recession.

At the risk of failing to do an in-depth report justice it drew out several significant points for credit investors. Firstly, defaults between 2007-2012 have come in significantly lower than most would have expected. Secondly, loss given default (the loss incurred if an obligor defaults) in the last couple of years has been trending higher. Finally, investment grade credit continues to overcompensate investors vis a vis historical default experiences. High yield credit less so.

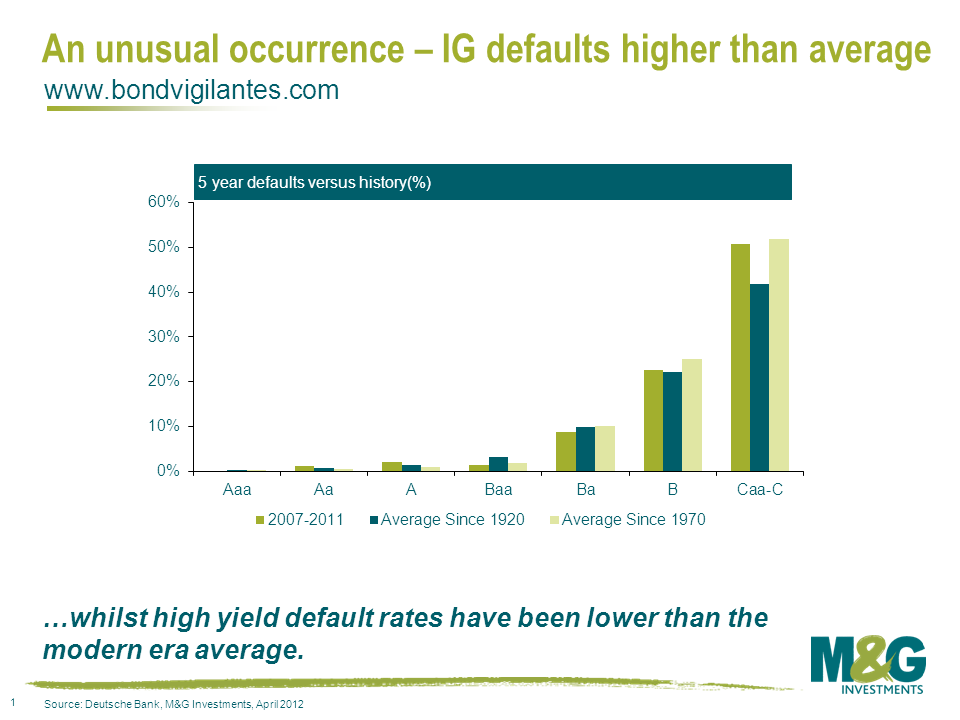

Whilst default rates have been decidedly ‘average’ over the last five years by historic standards, the statement masks an interesting picture. The below chart demonstrates that lower rated credit, especially sub-investment grade, has ‘outperformed’ the historic experience. Conversely Aa and A rated credit saw a higher default rate of 1.1% and 2.1% compared with a long run average of 0.8% & 1.3% respectively. Much of that can be attributed to the aggressive behaviour of financials (traditionally Aa & A rated) in the run up to the financial crisis and more conservative behaviour on the part of industrials. As Deutsche Bank argue, had we not seen massive intervention on the part of the authorities over the last five years then defaults would undoubtedly have been much higher. Perversely, it’s likely that the sheer extent of excess in the financial system forced intervention on a scale which artificially lowered the ‘market- free’ default rate experience.

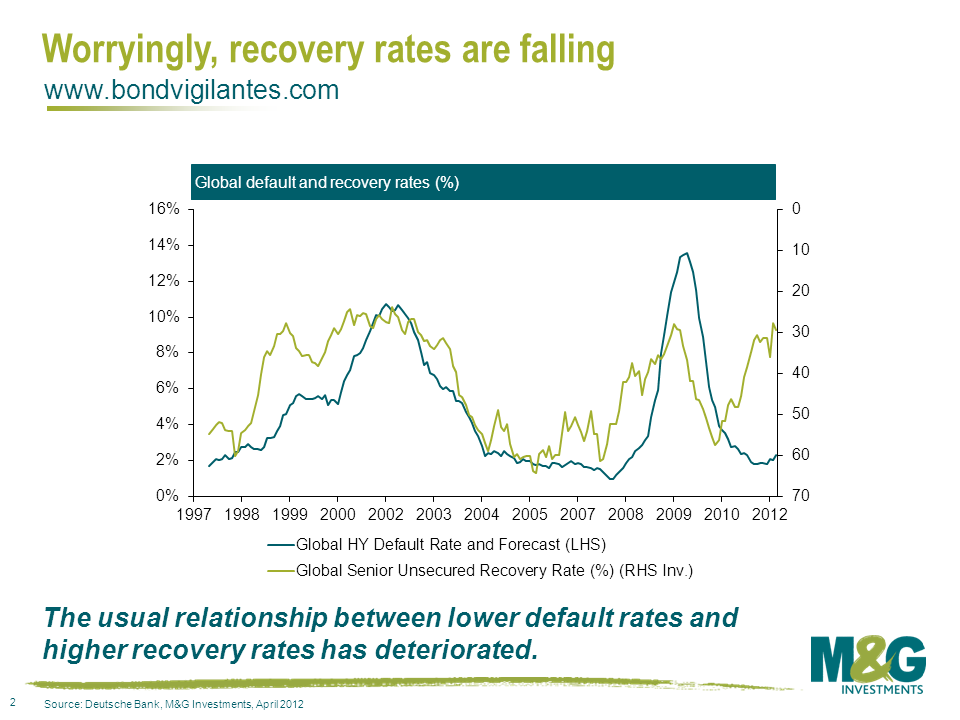

An examination of recovery rates shows that there has been an obvious weakening and worrying trend developing over the past eighteen months or so. The following chart demonstrates this is somewhat out of whack with previous experience. Low default rates should typically correspond to strong recovery rates, partly because they are normally accompanied by better economic times. The current ‘artificially’ low default rate has been accompanied by a broad lack of confidence and a challenging environment for capital raising. This has weighed down on recoveries. Whatever the reason, this is an important trend that requires monitoring. Whilst defaults and their numbers garner headlines the loss given default is more relevant for investors.

Given the weakening trend in recovery rates, it would seem appropriate to apply a conservative recovery assumption of 20%, half the 40% traditionally applied, when analysing whether credit is or isn’t overcompensating a buy and hold investor. On this basis, investment grade non-financial spreads continue to significantly over compensate for historic default risk. Based on current market corporate bond spreads, Sterling investment grade non-financial credit is pricing in a default rate of 12.7% over five years, and 12.0% for European non-financial investment grade credit. This compares to a worst case experience of 2.4% for both European and Sterling credit since 1970. Turning to high yield, and again assuming a conservative 20% recovery, the data is less convincing. Whilst broadly speaking investors are still being overcompensated for investing in the asset class with an implied 5 year default rate of 37.9% versus the long-term average of 31.6%, much of the value comes from BB rated credit. At current valuations B & CCC rated credit provides far less compensation for buy and hold investors and clearly support the need for in-depth credit analysis, especially because of the spread dispersion to be found in the lower rated areas of the high yield market.

As far as the outlook is concerned it seems a reasonable call to argue for continued low default rates amongst investment grade industrials in core European economies and the US. Liquidity remains ample, earnings remain broadly strong and financial discipline adequate. On the other hand, default experiences in the periphery and financial arenas are very much at the whim of the authorities. The adjustments needed will undoubtedly take time if they are to happen at all. Without the ongoing support of central banks and creditor nations it is unlikely that default rates will go anywhere but up.