Last week saw Citigroup’s credit conference & an opportunity for investors to catch up with a number of European high yield issuers. For a number of companies the message continues to be one of uncertainty, not least with regard to their banking relationships.

Back in 2008 Richard & I blogged about companies drawing down on bank lines (see here). Companies like CIT were doing so as they were finding it increasingly difficult to fund, whilst the likes of Porsche saw an opportunity borrow cheaply and then deposit the funds at a higher rate.

It seems once again companies are looking to draw down committed facilities. However, rather than being born out of an individual company’s distress, the catalyst seems to be the waning confidence in the banking system. At the very point in time when banks are finding it more difficult to fund their balance sheets and to deleverage, they risk seeing companies call on committed lines, which by their nature are not fully funded.

Which leads nicely into the Tuesday’s annual Sovereign and Financial System Review conducted by our financials team. The meeting focussed on the debunking of myths we feel broadly remain common place amongst investors.

Whilst the substance of the meeting is outside the scope of any one blog, and merely listing the myths taken out of context, I figured it was a worthwhile exercise anyhow to list those myths that have been debunked over the last 12 months or so, as well as those that continue to circulate:

The myths that are being debunked:

- No more banks will be allowed to go bust

- Banks have deleveraged already

- Banks have already restructured

- National champion banks will be fine

- Covered bonds are bullet proof

- Supra and agency bonds are ‘guaranteed’

- It’s ok, there’s a bail out fund

- Germany’s fine- they’ll bail us out

- Governments will abide by EU treaties

- Insurance Sector is a ’safe haven’

- You don’t need to do sovereign analysis

- Credit analysts can’t do sovereign analysis

The myths that are still believed to varying degrees in the market, or that have appeared recently, and give rise to the most discussion around here at the moment, :

- It’s easy, just look at the debt/GDP ratio (for sovereigns)

- It’s ok if you have commodity exports

- It’s ok if most debt held domestically

- Just look at net external debt

- Just look at current account deficit

- Sovereign debt doesn’t need documentation

- Eurozone breakup is unthinkable

- Docs or English law prevents redenomination

- Foreign bonds are in some way better

- You can work out impact of Eurozone break up

- Bond lawyers can tell you what you need to know

- As long as the bank is profitable, it’s ok

- XYZ bank is highly profitable based on its net interest margin

- Capital ratios or non-performing loan ratios are an indicator of solvency

- Leverage ratio (equity/assets) will be the most useful

- The yield curve determines how banks do

- Household leverage is an indicator of problems or a lack thereof

- Some banking sectors are ‘safe havens’

- Banks have improved their funding profile

- Banks have increased their deposit bases

- Banks have lots of collateral available

- Banks can always raise secured funding or repo

- Banks have successfully prefunded maturities

- National champion banks will be fine

- Government bad bank structures are working

- Central counterparties eliminate risk of financial defaults

- Repo market can value corporate bond collateral

- Repo market increases transparency

- Collateralisation has reduced counterparty risk

- “Too big to fail banks” will still get some sort of support

- Secured debt will be fine

- Agencies/supranationals are implicitly guaranteed

- It’s ok, the banks can just go to the ECB for repo

- National central banks can’t create credit

- A crisis is a buying opportunity

- We’re at the bottom, things will rally now

- Export/investment will recover quickly

- Asia/rest of the world will bail us all out

- Countries with own currencies recover quicker

Congratulations to those of you who made it to the end of that list. I imagine you are an elite few!

Travelling through Switzerland I can’t help but think that politicians both here and in the UK have a lot to thank their predecessors/electorates for. The relative safe-haven status enjoyed by both economies reflects, at least in part, the arm’s length relationship with the euro. (Swiss readers may not take kindly to being compared with us Brits, but you take my point.)

The eurozone policy makers who are currently trying to thrash out some sort of ‘deal’ have an almost impossible task on their hands. Despite a belated recognition that some leadership is much required, the reality is that a comprehensive solution won’t be reached. We’ve talked before (see here) about the inherent dangers in any monetary union absent fiscal union. Are the French, Italians, the Spanish, even the Greeks ready to be governed by Berlin? Or indeed, if Greece et al are willing to give up all sovereignty, are the Germans willing to take responsibility for the deficit countries of Southern Europe? Fiscal union requires both the debtors and creditors to be compliant. The foundations of the building are unsafe; replacing the roof may help keep the rain out but it won’t ultimately stop the house collapsing.

Absent fiscal union and two outcomes spring to my mind; euro breakup (of some form) or the monetisation of deficits. The former would likely see a return to 1930s depression economics, the latter some would argue risks a rerun of the 1920s Weimar experience. While we’re certainly not predicting a rerun of 1920s hyperinflation, it will be the temptation to inflate that will win out. The structural adjustments required of many European economies will likely prove too big a pill to swallow. German led protests will fall on deaf ears, and German resignations from the ECB will make little difference. Inflating away liabilities will prove an easier sell for economies that have binged on debt and leverage for decades.

Time to visit some inflation protection? Given there is so little inflation priced into bond markets right now, I think so!

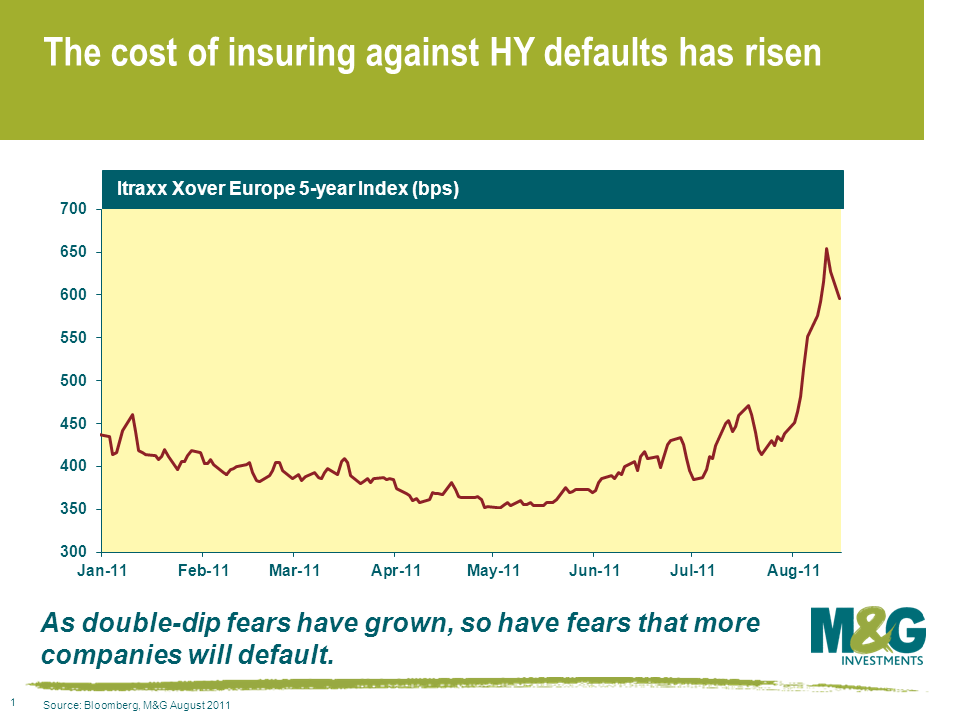

The price action in the high yield market has been brutal over the last few weeks. A very respectable year-to-date return of 3.8% as at end of June currently stands at -1.3% (according to the Merrill Lynch European Currency HY Index as at 15/08/11). That’s a significant re-pricing of risk. To put it in context, look at the iTraxx Europe Xover Index (for an explanation, see here). The most liquid vehicle in European high yield has seen spreads almost double from 350 in May to 595 today, and around 650 late last week. In other words, investors now require almost double the compensation for investing in the same 40 high yield names from three months ago.

Concerns around a stalling economic recovery & sovereign fears have seen investors redeem money in record amounts, forcing unprepared investors to sell indiscriminately into a very nervous buyer base. We’ve seen this sort of price action before – back in 2009, and it created some superb buying opportunities. Around $3bn of outflows were recorded in the US during the week to Aug 10th 2011, with the figure estimated to be around €600m in Europe. These are near record outflows respectively. Again taking the Xover Index as a proxy, the market is pricing in a default probability of some 42% (assuming a 40% recovery). Whilst this is some way shy of what the same index was pricing in at the nadir of the crisis, excluding CCC grade bonds, it is still pricing in a higher default rate than anything experienced in any five year period since 1970s.

Now I’d be a fool to call the bottom of the market here. If the global economy double dips, spreads will undoubtedly go wider again. Yet I am convinced that there are some bargains on offer. As James talked about in his recent blog, good old fashioned credit analysis is key. Where I can lend to sensibly capitalised businesses – with decent earnings prospects, strong liquidity, limited re-financing risk and good investor protection in the form of comprehensive covenants – I remain inclined to continue to do so. In a world where we expect interest rates to remain lower for longer, the 8-12% yields on offer from investing in senior secured paper issued by certain packaging and cable companies looks particularly attractive.

As a direct consequence of Moody’s downgrade of Portugal to sub investment grade, now Ba2 to be precise, Portuguese corporate bonds will be removed at month end from Bank of America Merrill Lynch’s (BofAML) main investment grade and high yield indices. This is because the main BofAML indices require the sovereign to have an investment grade rating. (It also looks as if Portuguese corporates will be thrown out of the iBoxx indices, although we don’t have confirmation on this yet). This will affect bonds issued by the likes of Portugal Telecom (PT) and Energias de Portugal (EDP – the electric utility) despite their current investment grade ratings. Those bonds are set to enter the BofAML Global Emerging Markets Credit indices.

Whilst some index focussed investors will be permitted to hold off -index positions, many will be forced to sell out over time, putting further upward pressure on bond yields. Since the start of the year, yields on EDP and PT 8 & 9 year bonds have risen by almost 2% to 7.5% & 8.75% currently.

Given the size of the Portuguese economy its corporates have historically constituted a small portion of broader Euro corporate indices (the same can be said for Greece and Ireland). As of yesterday’s close, Portuguese corporates comprised only 1.1% of the BofAML EMU Corporate Index. However, given the larger size of the Spanish and Italian economies it isn’t surprising to see their corporate bonds form a significant 14% of the index. And whilst Spanish & Italian government bonds currently remain firmly in IG territory, further downward pressure on those sovereign ratings will undoubtedly leave investors in peripheral European credit increasingly nervous.

It has been almost three years since the collapse of Lehman Brothers back in September 2008. The High Yield market has staged the sort of recovery few imagined possible, with each recent month bearing further witness to increased risk taking, evidenced by falling risk premia, record issuance and ever looser lending standards. With dividend transactions (Ardagh Glass), portable cap structures (House of Fraser/Odeon) & CCC issuance (Gala) all in evidence of late, is complacency setting in amongst investors? Is the HY market repeating the mistakes of 06/07 ?

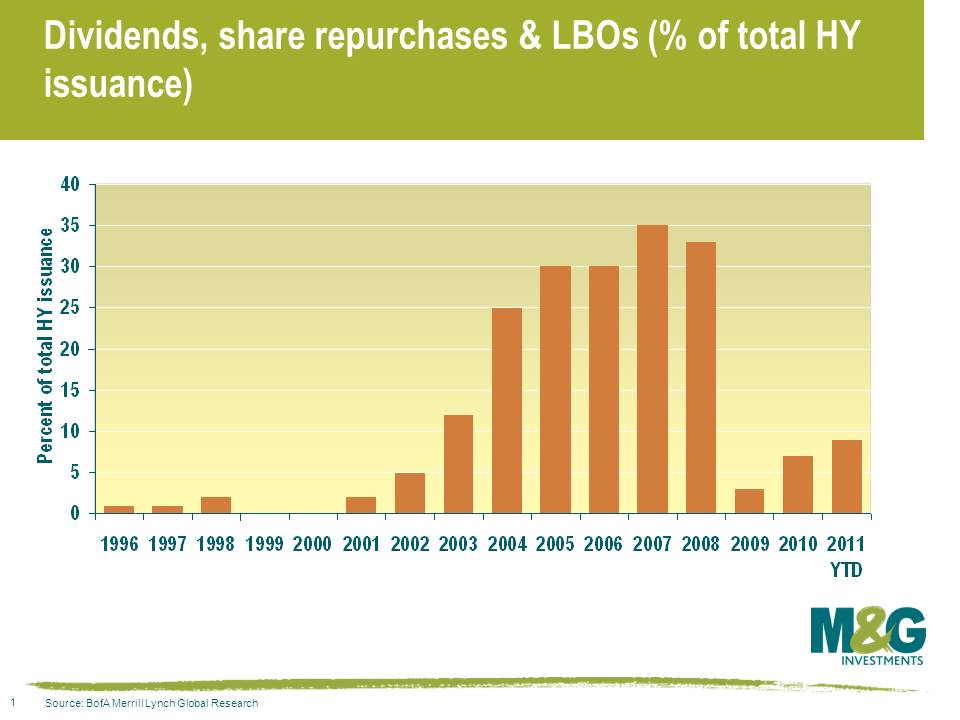

In two words; not yet. Comparisons will understandably be made between the lending practices of 2006/7 & 2011 but they currently remain fundamentally different. Consider first the use of proceeds of debt raisings. Unlike 2006-2008 the vast majority of new issuance has been to refinance existing bonds or loans rather than to finance new LBO’s. The more aggressive activity of 2005-7 – dividends, share repurchases and LBO issuance, remain at early cycle type levels (see chart 1). New issuance in EHY has been predominantly focussed on refinancing leverage loan debt rather than underwriting the sort of mega LBOs witnessed pre Lehman.

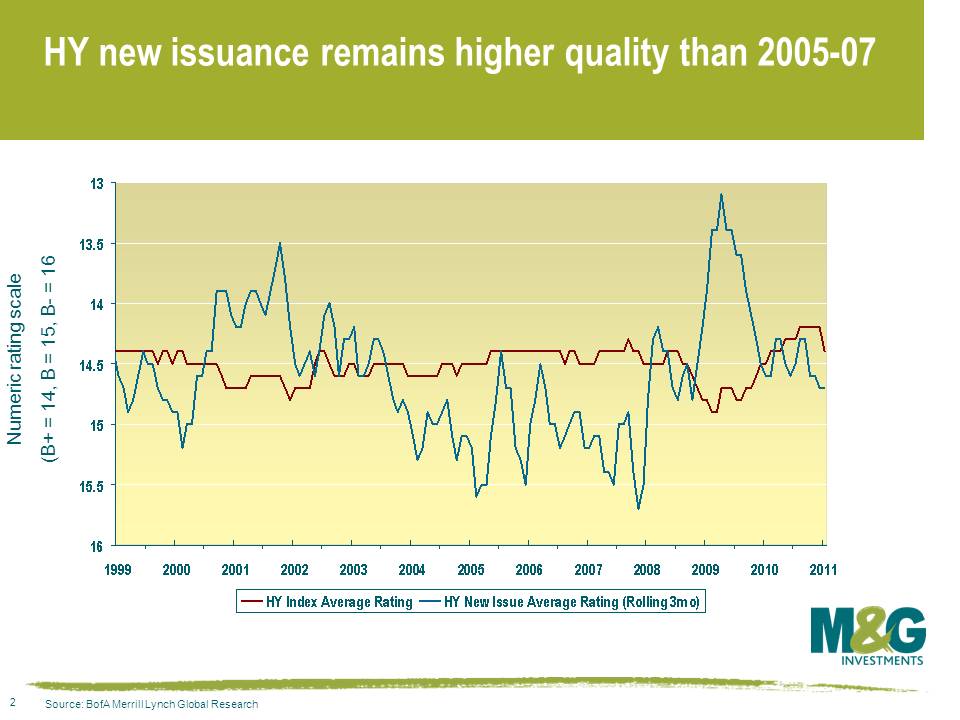

Credit ratings and leverage are other ways of comparing the two time periods. Whilst the market has indeed been willing to countenance lower ratings of late, CCC rated paper accounts for approximately 10% of issuance by volume against 16% in 2006. Despite the credit quality of new issues trending lower of late, it is still some way off of the quality seen in 2005-2007. (see chart 2) Leverage, or the amount of debt relative to earnings (net debt/ebitda), also suggests that current lending standards remain early/mid cycle like. According to Morgan Stanley, 1Q11 new issues saw leverage of around 4.6x, considerably lower than the 6x multiples of 2007. And finally, perhaps the biggest difference worth noting is the amount of senior secured paper being issued. Whilst 2006 saw €2.5bn of secured issuance, some 12% of the year’s total, Euro high yield has already surpassed €12bn so far this year, which is almost 38% of total issuance.

Talk of bubbles in high yield appears premature and the market is still some way off the heady pre Lehman days. That said, the on-going demand for yield may continue to pressure investors to take ever more risk, with issuers and sponsors looking on keenly. A pull back in risk appetite may yet prove healthy. Vigilance remains as relevant as it ever has.

The European Central Bank firmly laid its cards on the table at last Thursday’s press conference. Trichet et al are in no mood to risk potential second-round effects of rising wages. According to JP Morgan the phrase ‘strong vigilance,’ uttered by Trichet during his prepared remarks, was used one month prior to all policy moves during the last tightening cycle. Not surprising then that Bunds sold off and the Euro climbed. A 25 basis point hike in April to 1.25% is now all but a done deal.

Critics have weighed in with chants of an impending policy error on the ECB’s part. Whilst accepting commodity price inflation is clearly on the rise, there are limited signs of second round effects. As Jim wrote last month, recent union negotiated wage increases in Germany, Europe’s strongest economy, have proved fairly muted.

It’s hard to argue with claims that rate hikes will merely heap pain on an already embattled periphery. Coupled with structurally high unemployment, fiscal austerity and a seriously damaged banking system, the prospects don’t bode well for growth .

We know that the ECB’s primary and overarching aim is to ensure price stability. As the ECB notes “We… have as our primary objective the maintenance of price stability for the common good.” In fact, the ECB would argue that price stability is a prerequisite for long run sustainable growth and low unemployment. However, as we’ve argued before, if it comes down to a choice between protecting its inflation credentials and growth the ECB will side with the former. Is it right to damage Europe’s growth prospects to tame an inflation rate that currently stands at 2.3%, largely due to factors outside the ECB’s control?

Some argue that the ECB should not be so nervous about losing its inflation fighting credibility. As MPC Member Adam Posen points out in a recent speech, the Deutsche Bundesbank did not lose its anti-inflationary credibility post the oil shock of the late 1970s, despite inflation running above its 2% target for over six years. Posen claims that despite regularly overshooting both its inflation and money supply target, the Bundesbank was able to keep inflation expectations anchored through the “transparency and flexibility of its monetary framework.”

Perhaps the ECB should give serious thought as to whether it could also engineer a similar scenario. The consequences of prematurely embarking on a tightening cycle could prove disastrous for parts of the European Community and beyond; even if they’re only doing their job.

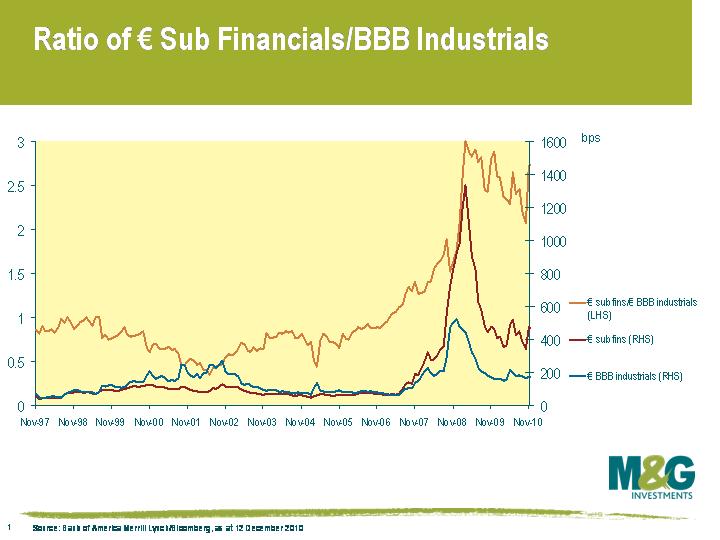

A renewed focus on European bank balance sheets, their sovereign exposures, fears of creditor bail ins and a general risk apathy saw subordinated financials spreads move significantly wider through November. I’ve charted the ratio of spreads, comparing the Merrill Lynch EMU Financial Corporate Index, Sub Type (EBSU) against the EMU Corporates, Industrial, BBB rated (EJ40) below. Whilst sub financial spreads are still somewhat tighter than levels reached in June 2010 ( +466 vs +519), the relationship between financials and non-financials has moved back to levels not witnessed since the end of 2009.

Where does this relationship go from here? Is a ratio near record wides sufficient to entice investors back into subordinated financials ?

Over the weekend Ardagh Glass announced a transformative acquisition of another well known packaging name in Impress Cooperative U.A. The deal left me with mixed emotions and came as something of a surprise because an IPO had been considered the most likely exit for sponsor Doughty Hanson.

The purchase of Impress sees the departure of a European high yield market stalwart. The company’s inaugural transaction back in May 1997 saw it raise DEM 200m paying a coupon of 9.875%. That was followed by a further €150m raised in 2003, paying a coupon of 10.5% until both bonds were called by the company in July 2006, the former at face value, the latter at a small premium, netting investors annual returns of 10%, give or take. Those obligations were replaced with the current debt stock, set to be retired again either at face value or a premium depending on the exact bond in question.

The sale to Ardagh Glass raises a couple of interesting points:

Firstly the IPO exit that never materialised. The ongoing volatility in equity markets, the scarcity of capital and the level of suspicion levelled at private equity from the public markets has resulted in fewer IPOs in recent times than many had imagined. Without a significant change in any of these conditions, the much touted IPO exit will give way to tertiary and secondary LBOs, likely accompanied by lower multiples and weaker IRRs.

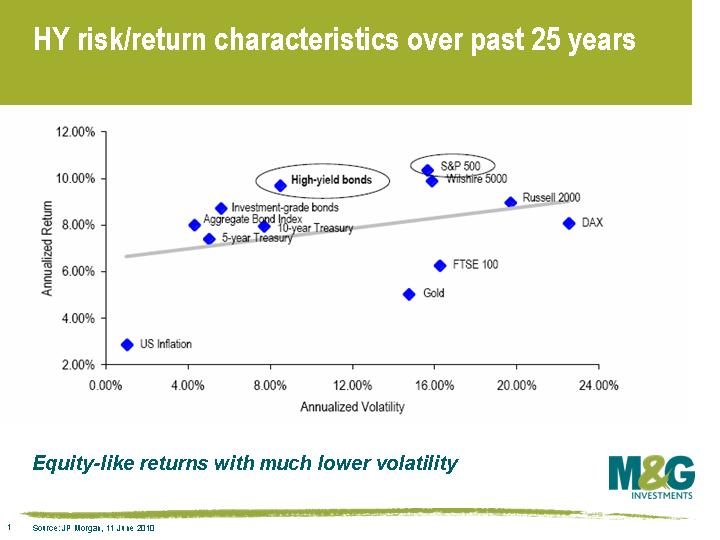

Secondly, the Impress story clearly demonstrates the attraction of high yield as an asset class. While it’s obviously disappointing to lose a conservatively run business (it’s all relative), with defensive and stable cash flows historically paying around 10% annually for its unsecured debt, it does highlight the importance of income and its ability to smooth volatility. In fact, comparing the US high yield market and the S&P 500, the two markets have realised similar annual returns over the past 25 years, yet the high yield market has done so with nearly half the volatility.

Travelling back from Sunday’s draw between Liverpool & Arsenal (it was never a sending off), I noted Liverpool Football Club had again made the business pages for all of the wrong reasons (see here).

The current battle between RBS, the principal creditor to LFC, and its owners Tom Hicks and George Gillett continues to highlight the dangers of utilising leverage to buyout companies in certain industries.

LFC was bought by the American pair for £219 million in 2007, including debt. Back in April of this year, and unable to re-finance the current £237 million of bank debt, Hicks & Gillett effectively defaulted and ceded management control to an independent Martin Broughton, as a condition of that re-financing. According to the Sunday press, a six month re-financing comes due on October 6th, along with a £60m penalty, at which point it is alleged RBS would take control of the club. No doubt potential suitors are well aware of the impending date and are biding their time, hoping to buy the club for the value of its debt alone. The most likely outcome, absent an earlier credible bid, is that RBS will again roll the loan in October, before finally selling the club later this year/early 2011.

So what has gone so spectacularly wrong off the pitch? Clearly the recession of 2008 proved a huge challenge to industry, although football, with a strong global support base actually weathered the storm comparatively well. Liverpool’s problems lie in the unsuitable debt load and subsequent demands placed on the club post the 2007 acquisition.

As potential debt investors in LBOs (see here) (typically through high yield bonds that are issued to help fund the transaction) we favour those industries and companies with stable and recurring cash flows. We also look for hard assets that we can fall back on if things were to go wrong (higher recoveries), as well as an ability to recognise synergies and operational improvements – leading to improving cash flow and profitability.

Sadly for the fans of clubs with spiralling debts, football fails to tick the boxes. The fixed nature of players’ contracts, an ever increasing wage/revenue ratio, and the ongoing pressure to compete with ‘trophy’ signings make the cash flow generation required to service interest costs a real challenge. Deloitte’s Annual Review of Football Finance 2010 (see here) makes interesting reading. Over each of the last three years the wage bills of Premier League clubs have grown in double digit percentage terms. ‘With wages growth outpacing revenue growth in 2008/2009, the Premier League’s wages/revenue ratio increased to 67% – a record high.’ The report goes on ‘[in] a classic example of competitive game theory, clubs are continually driven to maximise wages rather than profitability.’ Despite increasing income streams ‘the vast majority of those revenues will quickly flow into the hands of players and their agents.’ Clearly operational achievements will be massively hampered in any industry operating under said conditions.

Football clubs also tend to be asset-light businesses, with those assets that they do own proving difficult to value. What is Anfield worth if football isn’t being played there for example? How much is Wayne Rooney worth should he break a leg?

Beyond that, how willing or able would a lender be to enforce their rights in an event of default? Indeed, this no doubt partly explains RBS’s previous willingness to afford Liverpool’s owners extra time to find a buyer. Huge reputational issues aside, a punitive administration regime requiring a ten point deduction by the FA makes it a less than palatable option. Finally there is the issue of the super creditors rule, which places players, managers, the FA and other football clubs as preferential creditors in administration. The recent case of Portsmouth demonstrated that under these rules wealthy footballers are made whole ahead of HMRC. (see here)

The current underperformance of the high yield bonds issued by Manchester United in January 2010 (currently trading at 96% of face value to yield 9.6%) despite (sadly) strong performance both on and off the pitch, suggests other investors share our concerns. Whilst certain companies within industries such as cable and healthcare & packaging have proven themselves successful LBO candidates, most football clubs remain a far from attractive proposition for most debt investors.

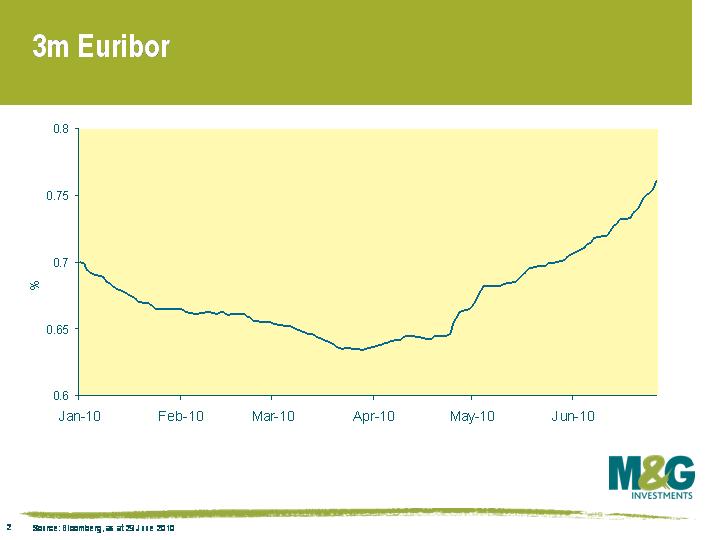

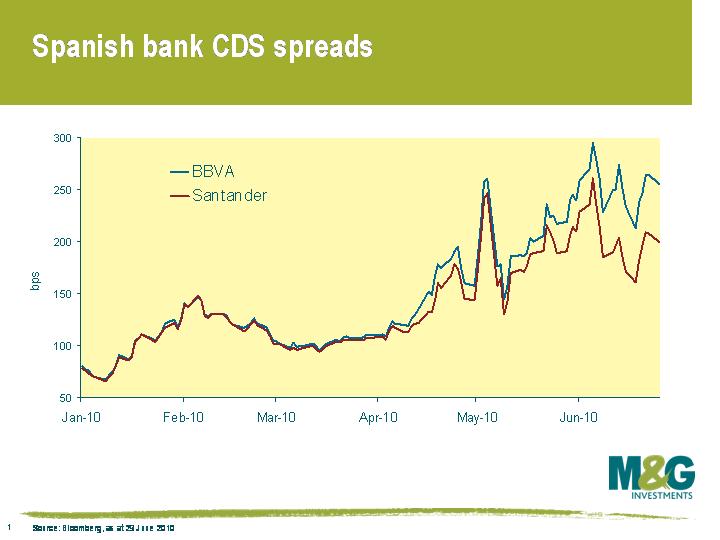

A report in the FT today highlights the lobbying of the ECB by Spanish banks to renew a one year funding facility known as the Long-Term Refinancing Operation (LTRO) that comes to an end this week. Banks borrowed €442bn from the ECB under the facility last year, at a time when borrowing in the market was either impossible or too expensive. When the facility closes, the banks that still need ECB funding will face two options – either roll into a 3 month facility, or into an even shorter 6 day facility. Banks worry that this shorter term facility will make their funding task more uncertain, and puts them subject to rollover risk when each facility matures.

This highlights two issues. The first is the difficulty that Spanish banks (amongst others) are currently facing in accessing the capital markets (see first chart). It will be very interesting to see just how much of the €442bn gets rolled because it will give us an indication of the reliance of European banks on the lender of last resort – on the FT blog they show the market’s expectation of the roll, and the implications of this as an indicator of banking system health (the more that gets rolled, the more worried we need be). To what extent are banks able to fund themselves in the open market at all? This second chart shows that strains in the European interbank market have intensified in recent days, with 3 month money market rates up from around 0.65% at the start of May to 0.76% now.

The second and perhaps larger issue is the risk to the anaemic European recovery that the ECB is taking. I’ve been critical of the ECB in the past, such as when it raised rates in summer 2008, and its obsession over fighting inflation. Now it wants to withdraw term financing from the market when arguably it is most needed. Shouldn’t they be cutting rates? Where’s the European inflation risk?

Whilst President Obama warns of the dangers of tightening fiscal policy too early in the recovery, Europe (and the UK) is backing austerity. The austerity measures that are being implemented across Europe may act as a drag on growth for some time to come. Who knows which is the right approach, but the tightening of liquidity by the ECB seems to be premature and misplaced. The European banking system remains on life support. Whilst European banks can continue to access 3 month unlimited tenders, the message from the ECB is that it is uncomfortable being the lender of last resort and that inflation remains the enemy. Unless the market’s perception of the ECB changes I fear European banks will continue to struggle on their path to recapitalisation.