At this stage the details are very limited but it appears that the German supervisory body BaFin has banned the “naked” short selling of Eurozone sovereign bonds, their credit default swaps, and the shares of ten leading German financial institutions. The ban was effective as of midnight last night.

This move by the German authorities has had the effect of spooking already fragile markets. As we have discussed before markets do not like a lack of transparency and these actions appear to be draconian and uncoordinated. The fact that the ban was announced after the European market closed and was implemented only a few hours later is nothing short of reckless and has the market speculating about larger, unknown problems.

The S&P 500 closed about 1.5% lower last night and European markets are currently seeing a flight to quality on their open.

This announcement appears to be largely symbolic and arguably politically driven. The vast majority of derivative trading that Germany has banned actually takes place outside of Germany. The German authority simply does not have the legal jurisdiction to implement the ban in major financial centres like London and New York in respect of non-German domiciled institutions. It is a question for the lawyers whether this ban extends to German domiciled financial institutions trading in different jurisdictions, either through branches of the German domiciled parent or through foreign domiciled subsidiaries.

I wouldn’t be surprised if domestic German institutions are able to find a way around the legislation. The unintended consequences may see ‘speculators’ merely reset their positions in markets that fall outside of the scope of the ban. Will investors express their negative view on Europe by further selling the Euro currency?

As with the recent $1 trillion package to support the Eurozone the short selling ban is an effort to buy time and take pressure off the EU economies. The fact is that neither of these actions address the long term solvency of a number of Europe economies and is likely to further set the cat amongst the pigeons.

Strong earnings results, low inflation expectations and a view that the ECB will have to keep interest rates lower for longer to support the economic recovery has seen demand for European corporate bonds remain fairly robust.

That is not to say that European corporate bond markets have been unaffected. Those credits that have been most impacted by the sovereign debt worries have unsurprisingly been domestic Greek and Portuguese corporations that have limited foreign earnings. It is clear to me that these corporations will continue to come under pressure from the market due to worries about lower earnings, higher taxes and continued speculation that some nations may leave the Euro. This is likely to be reflected in a higher spread for Greek and Portuguese corporate bonds over the equivalent risk-free government bond (which is currently German bunds). Some investors have sought the protection that is offered by credit default swaps (CDS) resulting in more pressure on cash bonds. CDS are seen as an early warning signal for bond markets, alerting investors to structural weaknesses before a crisis hits.

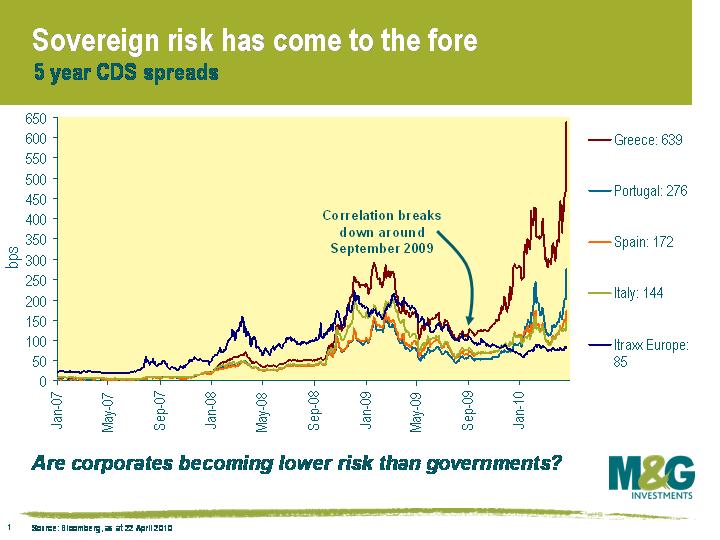

Interestingly, the once strong correlation between sovereign debt concerns and corporate bond markets appears to have now broken down. The iTraxx European index, a measure of creditworthiness of European investment grade credit, has tightened from September 2009. This is in contrast to countries that are located geographically on the periphery of Europe, where CDS spreads have had a tight correlation with Greek CDS. This phenomenon is highlighted in the attached chart. After the financial crisis of 2008 until September 2009, CDS spreads for investment grade credit and sovereign nations were highly correlated. Why is it that the risk of a sovereign crisis is not having the same impact on the European corporate bond market that it had from September 2008 to September 2009?

For me, there are a number of reasons. Firstly, unlike governments, companies have de-levered in the recession by cutting costs, unwinding or selling off assets, and have issued equity to retire debt. Secondly, unlike governments, companies have used favourable market conditions to extend their debt profiles. Thirdly, unlike governments, many companies are awash with cash. Fourthly, unlike governments, many high quality companies have not been affected by political uncertainties.

Given the above, I am not surprised that high-quality European corporate bonds have thus far remained insulated from the worries in sovereign markets. Corporations are operating from a strong starting position, with many having taken the necessary steps to improve their operating finances and balance sheets. Positively for the asset class, lending standards are improving and default rates may have peaked at levels that are much lower than the market expected. Corporate bond yields remain favourable, especially when compared to cash.

Peripheral European governments on the other hand are trying to stimulate weak economic growth, forcing them to borrow more and more. Rising government bond yields are making it difficult to borrow and causing debt servicing costs to increase markedly, as Greece has found out. Political tensions are rising, particularly in those countries where necessary austerity measures are required. Certainly, when economists from the Bank of International Settlements start writing things like “the aftermath of the financial crisis is poised to bring a simmering fiscal problem in industrial economies to boiling point” it is time to sit up and take notice.

The past couple of days have seen Greek debt take a bit of a battering. Spreads on Greek government bonds are the widest they have been since the inception of the Euro, and Greek 5yr CDS is wider by 100bps+ versus the beginning of the week. This seems to have been driven initially by nervousness around the anticipated bailout, with rumours that the Greeks are trying to renegotiate the deal that was announced on 26th March. More seriously though, Greek banks, who ironically were the ones responsible for buying a lot of recent sovereign issuance, have now asked for Eur14bn in loan guarantees from the government, perhaps due to recent numbers that showed as EUR10bn drop in deposits (4.5% of Greek GDP!). This could be the start of a bank run.

Looking to the relatively recent past one will find that Argentina underwent something similar. They went through their debt fuelled crisis in the ‘90’s, with a bank run in 2001 as Argentines withdrew money from banks and converted into US dollars, culminating in sovereign default in late 2001.

The parallels between the two countries are quite striking. Argentina used to operate a currency peg to the US Dollar (abandoned in early 2002), effectively the same as having a common currency, in order to keep a lid on inflation. Argentina therefore imported US monetary policy, resulting in an artificially strong currency, and this resulted in artificially high imports (which meant a steady outflow of US dollars from the economy). The currency peg also gave the Argentinian public access to cheap US credit, which they were less than reluctant to use. Greece too has spent the past decade or so borrowing at artificially low rates of interest.

Corruption and tax evasion in both countries exacerbated their problems. Admittedly appointing political supporters to Argentina’s Supreme Court and an (alleged) illegal arms deals could be seen as more morally questionable than cooking the books, but where markets are concerned dishonesty on any level is a serious offence.

The levels of debt of the two however are not comparable. Unfortunately for Greece, they are starting from a considerably worse position than the Argentinians. In 2001 Argentina’s debt/GDP ratio and deficit as a percentage of GDP were 62% and 6.4% respectively. At the end of 2009, Greece’s debt to GDP was 114% and the deficit 12.7%

After the Argentinian crisis, the IMF, who repeatedly lent cash to Argentina in the 90’s, produced an evaluation report entitled The IMF and Argentina 1991-2001. It’s quite a hefty piece but on pages 6 and 7 there is a list of lessons learned and recommendations on how to avoid mistakes in the future. To me, the most interesting lessons are lesson 9 ‘Delaying the action required to resolve a crisis can significantly raise its eventual cost…..’ and recommendation 4 ‘The IMF should refrain from entering or maintaining a program relationship with a member country when there is no immediate balance of payments need and there are serious political obstacles to needed policy adjustment or structural reform’. Recommendation 4 must be a particular worry to the Greeks. This crises has been dragging on for a few months now without any decisive action having been taken and disagreements between Germany and the rest of the Eurozone over whether/how to lend a hand could be viewed as a ‘serious political obstacle’. Clearly the disagreement is what has caused the delay in a resolution but the longer the policy makers procrastinate the more expensive an eventual bailout will get.

When Argentina defaulted, the government offered a debt swap valuing existing bonds at only 35% of face value, the worst recovery rate in sovereign debt history. 76% accepted these terms, but the rest didn’t (and the holdouts are still fighting with the government today, which has locked Argentina out of international capital markets since it defaulted). With over half of outstanding Greek bonds still trading with a cash price in the 90s, if Greece does default (implied risk from CDS market is over 30% in the next five years) then investors potentially still stand to lose over half of their money.

A further worry is that when Argentina defaulted, the consensus (seemingly as now) seemed to be that there wouldn’t be contagion (see here). True, initial contagion at the end of 2001 was limited, but contagion increased through the second half of 2002. Only a $30bn IMF loan prevented a Brazilian default in 2002, and Uruguay experienced a banking crisis and defaulted in 2003. Argentina’s default resulted in borrowing costs increasing significantly in the region, and growth for all countries stagnated. What is particularly worrying is that, unlike with Greece now, Lat Am banks didn’t actually have that much exposure to their neighbour’s debt.

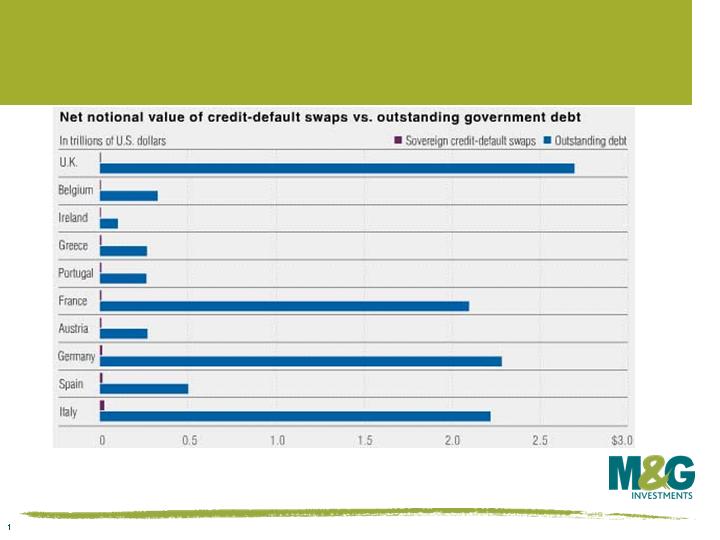

Following on from Jim’s Sovereign CDS Q&A blog (see here) I came across this chart at zerohedge.com. Whilst I can’t vouch for its accuracy, the chart shows that the actual net amount of outstanding sovereign CDS contracts, relative to outstanding government debts, are actually very small. That would seem to add weight to Jim’s argument that the pressures faced by governments are borne ‘of fiscal imprudence and a lack of will to resolve this,’ rather than the sole work of evil speculators.

Following on from Jim’s Sovereign CDS Q&A blog (see here) I came across this chart at zerohedge.com. Whilst I can’t vouch for its accuracy, the chart shows that the actual net amount of outstanding sovereign CDS contracts, relative to outstanding government debts, are actually very small. That would seem to add weight to Jim’s argument that the pressures faced by governments are borne ‘of fiscal imprudence and a lack of will to resolve this,’ rather than the sole work of evil speculators.

Back in January at our Annual Investment Forum I focussed on the changing face of the European Leveraged Finance markets – those companies financed with significant levels of debt. My belief is that the current, somewhat forced reinvention, will ultimately result in an increasingly deep and liquid European High Yield market (EHY), more akin to that of the USHY market.

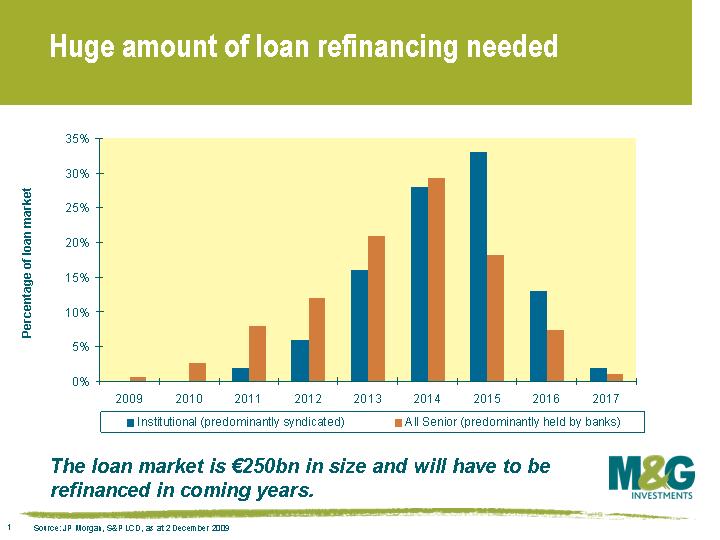

This change, which is already well underway is being predominantly driven by three factors. Firstly, a need within the European leveraged loan market to re-finance a huge wall of debts maturing between 2012 & 2015 (see graph). Secondly, we have witnessed a significant rise in the number of fallen angels issuers; those high yield companies who have lost their investment grade status, the likes of Fiat and ITV. Thirdly the now significant sub financial component of the high yield universe is changing the nature of the market. Subordinate debt issued by the likes of Lloyds, RBS and ING currently comprise around 13% of the EHY universe.

On my first point, the consensus has held that a mixture of trade sales, secondary LBOs, IPOs, restructuring and re-financings will offer a solution to the circa €200 bn worth of European leverage loans coming due. However, the recent decision to abandon attempts to IPO Travelport, and delay those for New Look and Merlin, has brought the spotlight firmly on the IPO market asking questions of its willingness to participate in future.

The European equity market has arguably learnt some harsh lessons over the last few years. The relisting of Debenhams back in 2006 was followed by three profit warnings in quick succession with its stock price predictably suffering. (See Times article here) Gartmore and Smurfitt Kappa’s IPOs are other examples of sponsor owned businesses that come to mind whose stock prices have underperformed the market since relisting. Had much, if not all of the low hanging fruit already been extracted by the sponsor?

In today’s volatile environment the ability of private equity to hit their IRR targets may be hampered by the scepticism pervading the European equity markets. The reality is that there will always be an equity market interest in backing companies with good prospects and strong track records, sensible debt levels and an alignment of sponsor/equity market interests. But the lack of willingness to underwrite the IPO’s of highly levered, cyclical businesses poses further questions for the European leveraged finance market. If the European equity market is unwilling to play its part in re-financing the excesses of previous years, then the implications are likely negative for both private equity returns and certain European leveraged finance investments.

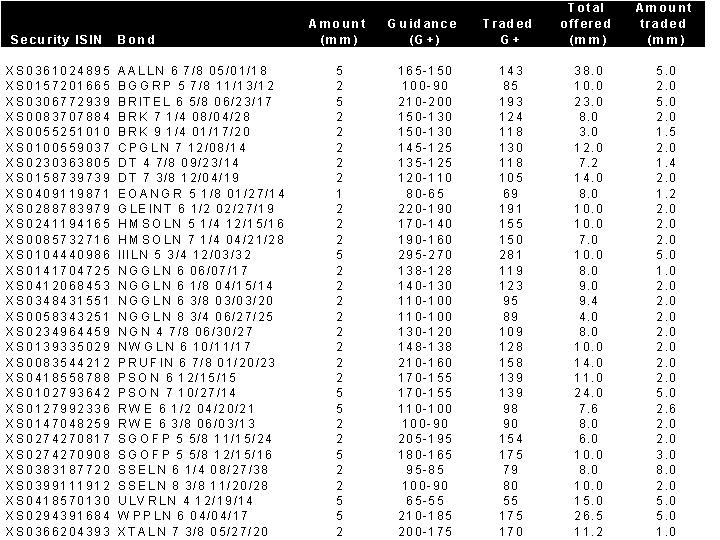

Last week’s BWIC list (bids wanted in competition) from the Bank of England gave further evidence, if it was needed, that the demand for Sterling corporate bonds remains very strong. The table below, kindly provided by HSBC, shows the bonds that were sold and that most traded through where the market was pricing them last Friday.

The BOE took the opportunity to sell a selection of the corporates it purchased in its QE program of last year. Despite receiving bids for every bond on the list The Bank decided to sell a mere £83.7m worth, or one quarter of the £324m bonds that were on offer. Running a ruler over the levels achieved in the auction The Bank achieved new highs for many of the bonds that were sold.

A year ago Richard wished the BOE every success as corporate bond fund managers, so far so good. Analysts over at Evolution Securities have since calculated that the BOE has so far earned around £60 million on the £1.55 bn portfolio of bonds they currently own. Not a bad return considering the Bank’s ability to print money and therefore to finance at no cost. Coupled with evidence from previous banking crises such as the Swedish one back in 1992, The Old Lady of Threadneedle may well see a tidy profit from its actions.

List of Bonds

It’s been quite a year to date for leveraged finance. Improving economic data, increased risk appetite and a supply/demand imbalance has driven valuations starkly higher. At the time of writing, the Merrill Lynch European High Yield Index is up a whopping 75%, the average bid for leveraged loans in Europe has risen by around 50% from its lows earlier in the year, and the high yield new issue market has reopened to all but the most speculative propositions printing approximately €20bn year to date.

Such a reversal in fortunes is bound to be met with raised eyebrows. Standard & Poors, in a report released last month asked ‘Is History Repeating Itself In The European High Yield Market?. The report identifies four areas where it claims the European high yield market is at risk of repeating past mistakes. I thought it would be worth taking a brief look at each.

The first area relates to pricing. ‘The lack of returns in money markets and investment grade bonds may be prompting new investors to enter the European high yield market, compressing spreads as volumes remain low’according to S&P. I have some sympathy with this notion. The lack of supply in the earlier part of the year combined with a near zero interest rate policy has undoubtedly forced less traditional investors to consider high yield risk. The huge oversubscriptions that new high yield transactions have garnered in recent months are, in part, testament to the idea. There is evidence that suggests that this interest has broadly targeted the stronger high yield credits and in itself has not been the major driver of lower spreads. An improving default outlook and economic backdrop has likely played a greater part.

The second area of concern relates to the recent non-rated issuance. ‘Anecdotal evidence suggests that much of the demand of unrated deals comes from private banks and other relatively new players’according to the report. I suppose we have to take this gripe with a pinch of salt. S&P are clearly incentivised to ensure the status quo of obtaining a rating prior to, or shortly after, coming to market. That said I don’t doubt that a number of investors have bought recent unrated transactions without the skills to fully analyse these investments.

The third area relates to the structuring of transactions. This and S&P’s final point are those with which I have the most sympathy. ‘Bond covenants have not been particularly strong for unsecured high yield debt’according to S&P. The ability of bondholders to protect their interests (and interests in the event of distress) will largely come down to the covenants that are put in place at the time a deal is structured. Indeed, a number of recent high yield transactions have come to market with the lack of covenant protection usually associated with investment grade rated transactions. This has been a major issue for us for a number of years (we have blogged on the subject on numerous occasions) and this has been one of the most important determinants when deciding on new transactions. Furthermore, we have long been advocates of a move to a US style approach of disclosing bank debt covenants. These covenants remain ‘private’ in Europe despite the dangers that this presents to investors.

The fourth and final area relates to disclosure. Historically high yield lenders receive detailed quarterly company reporting, whereas bank debt investors receive monthly updates. The more recent trend for certain high yield issuers has been for semi-annual reporting without an acceptable degree of detail.

Looking at the high risk end of the credit spectrum, it’s worth noting that CCC issuance has been notably absent so far this year. For example, a recent speculative transaction for Donington Park failed to get out of the pit-lane due to a lack of investor demand. Both are signs that we have yet to retest the heady heights of 2006 where credit was bountiful and there was a boon in speculative-grade bonds. That said, we are clearly trending back in that direction if spreads continue to compress for this type of debt. Such a trend will require close monitoring.

Having recently recovered from my amateur stunt man escapades I thought I’d pen a short note on the recent court sanctioned debt restructuring by IMO Carwash.

Why do investors outside of IMO care ? Well, it’s the first time that the English courts have been asked to rule on the issue of valuation in the case of a company restructuring, and it has implications for senior & junior lenders in both the high yield and leverage loan markets, particularly in light of the rising default rate.

The case recently ended up in court after the LBO ran into trouble and the proposed restructuring left no value for the mezzanine lenders. Mezzanine finance is usually the most junior debt a company will issue, senior only to the equity. The original plan was for the senior lenders to have their debt swapped for virtually all the equity in a new company, cutting the junior lenders out. The senior lenders argued in court that the mezzanine lenders had no economic interest given that the value of the assets was less than the value of the senior debt. The mezzanine lenders countered that this was an unfairly good deal for the senior lenders, arguing that the deal was being struck at trough valuations. Ultimately the judge ruled in favour of the senior lenders, dismissing the arguments of economic interest made by the mezzanine lenders.

As a result of this ruling, senior lenders are likely to gain more confidence in their ability to exclude junior creditors in future restructurings and perhaps increase their willingness to enforce their rights in certain circumstances. As investors in senior and subordinated debt, we have long recognised the increased security afforded to senior lenders.

The coming years will see further restructurings as a number of the aggressive leveraged finance transactions of previous years find themselves in difficulty. We’d expect the implications of this recent ruling to be felt by many more mezzanine lenders.

We’ve talked about new issuance a few times recently on this blog (see Matthew’s blog from December here and my more recent comment about the record issuance in Q1 here). But the focus has been firmly on issuance in the investment grade market, until now.

The European public high yield primary market was essentially closed for 18 months, with no new issues at all from August 2007 until January this year. This is perhaps not surprising since a lack of risk appetite, combined with forced selling led to a huge blowout in high yield spreads, with the spread on the Merrill Lynch Euro High Yield Constrained Index peaking at 2298 bps over government bonds on 18th December. This therefore meant a massive increase in the cost of borrowing for sub-investment grade companies, which had been spoiled for many years with extremely low financing costs.

But spreads have tightened considerably so far this year and a handful of companies have taken advantage of the improved sentiment to return to the debt market. German medical company Fresenius was the first, issuing new bonds maturing in 2015 with a 8.75% coupon back in January, and in the past couple of weeks paper company Stora Enso and Dutch cable operator UPC have tapped existing issues (both coming on the back of reverse enquiries from existing bondholders). On top of this, yesterday saw a new five year issue from drinks company Pernod Ricard, which priced to yield approximately 400 bps over government bonds, and today Virgin Media is issuing bonds with euro and dollar tranches, slated to yield around 10.25%, in order to prepay some of its outstanding secured loans.

This is obviously good news for the high yield market, which has been pretty illiquid for some time. We’re not getting carried away though. So far we have only seen new issues from the higher rated end of the credit spectrum (Pernod is rated BB+ by S&P for example), and from names that the market is pretty comfortable lending to. Many of the more aggressive high yield companies are unwilling or frankly unable to raise capital in either the bond or equity markets. Restructurings and defaults are still the likely order of the day for many of these businesses despite the improving risk sentiment.

We commented in November that growing levels of new issuance suggested that there were cracks in the ice in credit markets. This trend has rapidly accelerated. In the first quarter of this year, there was over €115bn of new issuance from corporates, almost twice as big as the previous record from 2001 and only slightly less than the €133bn figure for the whole of 2008.

We commented in November that growing levels of new issuance suggested that there were cracks in the ice in credit markets. This trend has rapidly accelerated. In the first quarter of this year, there was over €115bn of new issuance from corporates, almost twice as big as the previous record from 2001 and only slightly less than the €133bn figure for the whole of 2008.

Why has there been so much issuance? Part of the reason is that there was a backlog of refinancing that needed to be done in September and October 2008. But a bigger reason for the surge in issuance is that banks are not able or willing to lend, and if corporates are not able to raise finance (or refinance) with banks then they have to seek alternatives. And the only alternatives are issuing bonds to (ie borrowing from) people like us, or by tapping the equity markets via rights issues.

Just as an increase in government bond issuance doesn’t necessarily mean falling government bond prices (see previous blog here), surging corporate bond issuance doesn’t mean falling corporate bond prices. Taking Merrill Lynch indices, euro denominated investment grade industrials returned +4.1 in Q1%, 3.4% ahead of German government bond returns. Sterling industrials returned +4.2% in Q1,which was 5% higher than the return from gilts.

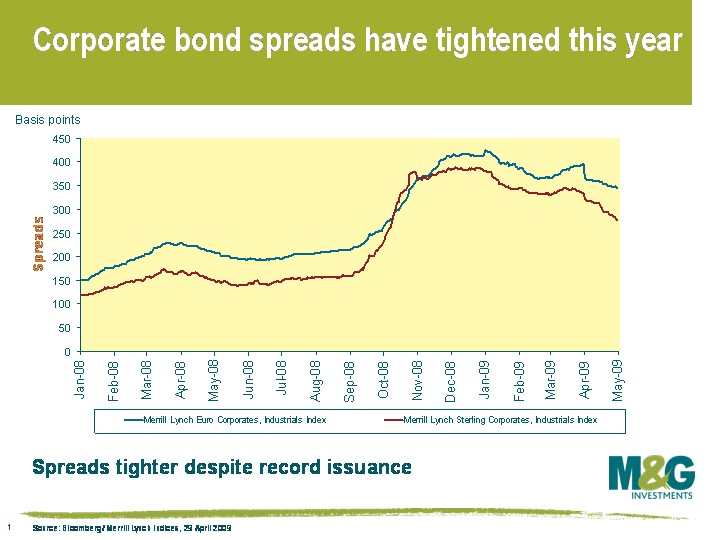

This chart shows how spreads in industrials (i.e. anything that’s not a financial or utility) have tightened over the past three months – euro industrials spreads are at least 100bps tighter than the wides hit in mid December, while sterling spreads are about 70bps tighter. (Note that at the end of May 2007, Euro industrial spreads were just 50bps over government bonds, and sterling 80bps). Spreads remain very attractive in a historical context, and spreads on new issues also continue to be attractive versus spreads in the secondary market.

This chart shows how spreads in industrials (i.e. anything that’s not a financial or utility) have tightened over the past three months – euro industrials spreads are at least 100bps tighter than the wides hit in mid December, while sterling spreads are about 70bps tighter. (Note that at the end of May 2007, Euro industrial spreads were just 50bps over government bonds, and sterling 80bps). Spreads remain very attractive in a historical context, and spreads on new issues also continue to be attractive versus spreads in the secondary market.

We expect this flood of supply to continue through this year as companies refinance and banks continue to curb lending. However, we do expect it to fall back later this year and next year. Debt buybacks are already happening, where some companies have been patching up their balance sheets by issuing equity to buy back debt, and we expect this to increase. Many companies simply don’t have efficient capital structures for today’s markets, now that the cost of borrowing is so much higher than it was. Debt buybacks are good news for bond holders, but not necessarily good for equity holders. As companies buy back debt and new issuance falls, credit spreads should tighten fairly rapidly.