After last week’s doom & gloom (see here) all appears significantly more rosy at the start of this week. The iTraxx Crossover index, currently trading at 285 as I type, is tighter than the 310 highs reached during last week with other areas of the market also bouncing back. Will it last? Well, this week’s plethora of data could give a good indication and potentially set the tone through the summer.

Firstly the earnings season in the US really kicks in with 80 of the S&P 500 names reporting. Of those names approximately 50 are financials, including Washington Mutual, JP Morgan, Merrill Lynch, Citigroup and Bank of America. The Q2 figures and Q3 guidance will be watched very closely for indications of just how significant an impact the current US sub prime debacle is likely to have upon earnings. Secondly Fed Governor Bernanke will give his semi annual Humphrey-Hawkins testimony to congress on Wednesday with the Fed minutes to be released the following day. Finally there is a whole raft of inflation, confidence, manufacturing & housing related data set to be released both in Europe, China & the US.

I personally, can see a scenario whereby the pending earnings data surprises to the upside and enables credit markets to rally in the short term. However, for the many reasons we have laid out in this blog I continue to be happy with maintaining a short risk position in credit.

John Waples wrote in the Sunday Times (read article here) on a theme we have been discussing for quite some time – ever increasing activism amongst investors. He points to a number of examples. Cadbury Schweppes, ABN, Rentokil & Vodafone have all come under pressure from equity investors of late “to release value and change corporate structure or management.” The message it seems is getting through loud and clear. Only this week we’ve seen ConocoPhillips and Johnson & Johnson approve $15bn & $10bn share buybacks.

Corporate bond markets are now also starting to get the message. I wrote a couple of weeks ago about the lack of confidence in the credit markets, but the situation has since worsened. Despite Moody’s recent default report showing a drop in the global default rate to 1.38% (the lowest for 12 years), and despite there being just one default in Europe this year, the current iTraxx Crossover Index is now trading at all-time wides. In fact, the index which comprises the forty most liquid high yield credits in Europe (see here for an explanation) is currently trading 35% wider than the tightest spreads witnessed in May.

The index has traditionally been positively correlated to the equity markets, however for now at least, this relationship has been cast aside. The path of least resistance continues to be spread widening and with a large pipeline of deals to come to market (especially in the US) the jitters, it seems, are set to continue.

It would appear that the distinct lack of confidence that I alluded to yesterday, (see here) has led to one or two interesting developments in the primary markets (the market for new debt issuance). Private equity houses KKR, Clayton and Dublier & Rice were, yesterday, forced to drop their bond offering funding the acquisition of US Foodservices. Covenant weak leveraged loans have also been receiving short shrift of late. Earlier this week Arcelor Mittal were also forced to pull their bond offering “pending more stable conditions.”

These developments will be a concern, especially to those banks who will have provided bridging finance and now have their capital tied up, at least until investors can be persuaded to part with some cash.

Sent by anonymous, 4 June 2007:

As an investment IFA I can sympathise with the question dated 23.05.07 – in relation to asset allocation and the resultant bond exposure so many stochastic modelling tools tell us to have. We have been underweight in Fixed Interest in general as an asset class for about 1 year now and going overweight in UK commercial property funds. This I am now taking back down to neutral (as I think UK property has had its day) – but I am still nervous about increasing the fixed interest exposure. I have looked at funds that use the UCITS III powers ie "strategic" bond funds and have to say that they look exciting. On the flip side however, I read a report that suggests some managers do not have sufficient knowledge to use the derivatives effectively and this could cause a major problem.

I would be interested to hear your views on this topic – particularly in relation to CDS, CDOs and the impact the US sub prime market problems could have on these.

The CDS (Credit Default Swap) market has developed rapidly, and in just a decade is now more liquid than the conventional corporate bond markets. There are undoubted benefits to CDS, namely that derivatives can provide investors with pure exposure to a company’s credit risk (so it doesn’t matter whether interest rates go up or down), and investors can make money from correctly forecasting that a company’s credit worthiness will deteriorate. The development of CDS has also been integral in spreading and diversifying risk within the economy as a whole, although the sheer size of the market has led to concerns.

The biggest worry is whether derivatives can withstand the impact of a large unforeseen shock. By definition, it’s not possible to predict a large unforeseen shock, but all we can say for certain is that there will be one. Last week, Terrence Checki, a vice president at the New York Federal Reserve, warned that "abundant global liquidity has been a powerful wind in the back of economic and policy progress and has bought substantial benefits [but] as we all know, liquidity is ephemeral: it disappears at the most inconvenient times". This is precisely what happened after the Russian default of August 1998, which was the last quake to shake the bond markets.

The Russian default caused financial markets around the world to seize up. Global liquidity evaporated, even for US Treasuries. The sudden and sharp spread widening wreaked havoc on what were supposedly low risk investments. Higher risk investments were inevitably hit hard – between July 20 1998 and October 5 1998, the FTSE 100 fell from 6179 to 4648. Perhaps the highest profile collapse was that of the Long Term Capital Management (LTCM), a hedge fund that lost almost $5bn in a matter of months and had to be bailed out by the Federal Reserve in order to prevent a widespread global meltdown. Now that the derivatives market is many times bigger than in the 1990s, what will the impact be of another Russia?

The problem is that the CDS market hasn’t been properly tested yet, because defaults in the global bond market have been incredibly low for an almost unprecedented period of time. This is not to say there have been no defaults at all though – Delphi, the world’s biggest auto parts manufacturer, defaulted in 2005. Delphi had around $2bn worth of bonds outstanding, but the value of the CDS riding on Delphi was over $20bn. Traditionally in the CDS market, contracts were settled by delivering the actual bonds, so investors that had bought protection needed to go into the market, buy the defaulted bonds, and then sell the bonds at par (100% value) to investors who had written protection. With Delphi there were concerns that the huge number of derivatives would create settlement problems, however a large proportion of the derivatives were either netted off against each other or settled for cash, and settlement in the end proved fairly straightforward. Cash settlement is becoming the norm in the CDS market, and the risk of any major settlement issues cropping up in the future is falling as the market becomes more transparent and efficient.

Moving onto CDOs (Collaterised Debt Obligations), the issues facing CDO investors (specifically synthetic CDO investors) are similar to those facing CDS, because synthetic CDOs are invested in CDS. With a CDO, an investor can choose precisely how much risk they want to take. Someone who invests in an equity tranche faces potentially large rewards but knows that if the portfolio is hit by defaults then they will be the first taking a hit on their capital. An investor in an AAA rated tranche of a CDO knows that he or she won’t lose any money until all the investors ranked beneath them are wiped out. The risk facing CDO investors, though, is knowing how much risk they are actually taking. There’s been a fair amount of criticism directed towards ratings agencies (see here for a good piece from the FT) who, it is argued, aren’t up to the job of rating sophisticated structured products. Does a AAA rated synthetic CDO tranche really carry the same default risk as a US Treasury? We’ll only know for sure when there’s a liquidity crunch.

The woes of the US mortgage market have hit a number of CMOs quite hard (CMOs are like CDOs, except the underlying portfolio is invested in mortgages rather than bonds). We’ve covered the US sub prime mortgage market in a fair bit of depth on this blog (see here, for instance). The yield on a number of CMO tranches that were previously rated investment grade suddenly shot out to 15% once the size of the collapse became apparent, but at the moment, it doesn’t look like the US sub prime crisis is the next Russian default. After pausing for breath, equity markets have more than recovered their losses and jumped to record highs in the US.

Finally, the concern over fund managers’ experience in dealing with products and instruments such as CDOs, CLOs and CDS is certainly a legitimate one. Some asset management firms are able to rely on their experience in alternative assets to build up the necessary operational infrastructure. M&G are lucky to have a market-leading CDO team who have been using CDS for over five years. The use of Value at Risk (VAR) analysis is also critical to control portfolio risk. But it’s less likely to be an operational issue that hurts investors rather than bad judgement from a fund manager. Investors need to be aware that while buying protection is not a risky strategy, since the downside is capped, writing protection has the potential to result in a fairly large loss. Given our views on credit risk in the corporate bond market, Richard Woolnough has mostly used CDS to buy protection in the M&G Optimal Income Fund, since he thinks there are a greater number of unattractively priced corporate bonds out there than attractive ones. When the next Russia comes along, it will likely be those funds taking excessive risk by writing protection on companies whose bonds default that will feel the pain. In short, if you make bad investment decisions using CDS and CDOs you will lose money, just as you would in traditional instruments, but there is nothing intrinsically bad about the derivatives and structured credit markets, and indeed they are often used to reduce and diversify risk rather than increase it.

With a less than satisfactory ‘I told you so’ look from Jim scant reward for my efforts in attending this year’s Champions League Final in Athens, I’ve taken more heart from the continued data flow (click the chart to enlarge) supporting my view of higher interest rates for Europe. In addition, I experienced first hand some inflationary gouging by the Greek taxi drivers – a temporary, and unofficial, cartel imposed supplement of 20 Euros for all Liverpool fans for any journey.

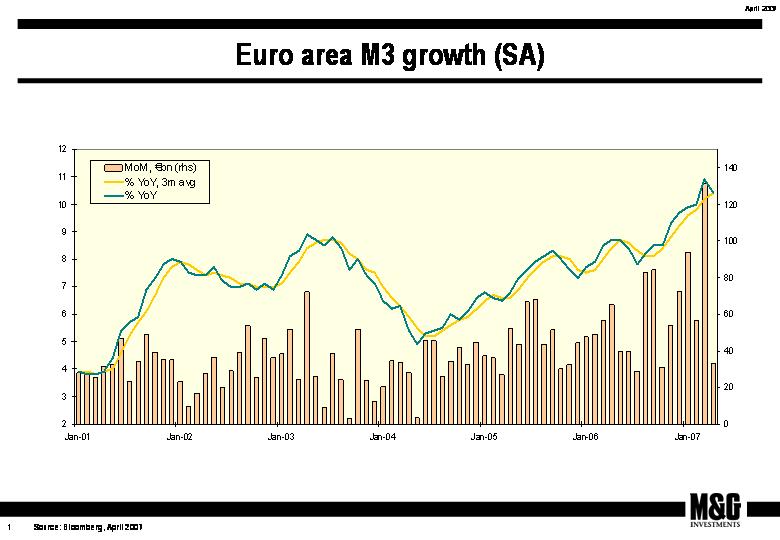

April’s money supply data released earlier today by the European Central Bank showed a slight deceleration from March’s reading of 10.9% YOY growth to 10.7% YOY, though these figures needs to be put into context. At 10.7% the growth in money supply remains well above the 4.5% level that the ECB considers non-inflationary and remains one of the key measures they will use to gauge future inflation. M3 money supply has remained above this 4.5% non-inflationary level since early 2001 with no real sign of abating, despite seven rate increases since late 2005. Indeed the ECB is extremely concerned that this excessive liquidity will drive prices up, pushing inflation above the 2% annual target.

At last month’s press conference, ECB President Trichet signalled a hike in June to 4% but since then, continued rises in oil prices, tight labour markets and strong capacity utilization data are likely to add further fuel to the fire. Indeed the futures market is already anticipating at least another hike to 4.25% by year end with ECB member Garganas stating today that they will keep their options “open” beyond June.

Whilst US rate cuts are looking less likely now – a long pause looks the best bet – I can’t see what (besides perhaps a stock market crash?) can stop the ECB from continuing to “normalise” European monetary policy. I’ll continue to run a short duration (bearish) position in the European Corporate Bond Fund in the face of such compelling data.

‘Takeover Tuesday’ was a phrase I came across describing several M&A deals announced earlier this week (Thomson & Reuters, Heidelberg & Hanson etc) and no doubt many more will follow in the coming weeks and months. I and other members of the team have written at length about this releveraging of corporate balance sheets, its implications for the corporate bond market and the implications for our funds (see links at bottom of this article).

As a brief reminder, the reasons for this releveraging are relatively low global interest rates, low market volatility, high risk appetite, ever more aggressive and cash heavy private equity funds. Looking forward, healthy corporate balance sheets and equity earnings yields above the real cost of corporate debt all support the continuation of this theme.

In fact a recent research piece by UBS suggests that we are merely mid cycle with a worldwide capacity for over $2 trillion in buyouts during 2007, and interestingly, what was once largely a US phenomenon is now far more balanced globally. But what if, as the data seems to suggest, much if not all of the low hanging fruit has now been picked?

The result is that we are likely to see ever more aggressive leveraged buyouts. Companies that no longer demonstrate many of the characteristics that have historically been considered a prerequisite of an LBO (be those size, positive cash generation, low leverage, defensive margin profiles to name a few) are now very much on the radar for private equity. In a corporate bond market priced to perfection this concerns me and accordingly I remain cautiously invested.

Other stories of interest:

– 26/04/07: Default rate is the lowest in 10 years, but the only way is up

– 30/03/07: Record global M&A activity in Q1

– 28/02/07: The long term effects of PE

– 11/12/06: Letter from New York Part II

– 16/11/06: Private equity continues to dominate the investment headlines

Moody’s monthly default report shows that the global speculative grade default rate fell to the lowest level since April 1997. March’s figure was 1.41%, down from 1.58% in February, which means that just 1.41% of all high yield issuers defaulted in the 12 months to the end of March. These incredibly low default statistics have been made possible by a combination of strong corporate earnings and relatively cheap available finance, which have also helped equity markets to rally (the Dow Jones broke through 13,000 for the first time on Tuesday).

However Moody’s predict that the global speculative default rate will rise fairly steadily from current levels up to 3.5% by March 2008. To be fair, their model’s credibility has fallen a little recently (it has been predicting a rise in defaults for about a year, while defaults have in fact fallen), but there is growing evidence elsewhere that spreads could widen soon, and a sharp correction is possible.

A fascinating note from Tim Bond, a very influential global strategist at Barclays Capital, paints precisely this picture. He argues that US companies are spending much more on buying back equity than on capital expenditure relative to in previous cycles (in Q4, US non-financials bought back the equivalent of 6% of total market capitalisation – by far the largest corporate buying spree on record). This expenditure is being financed by heavy issuance in the bond markets as companies take advantage of historically low yields and record tight spreads to raise finance cheaply, behaviour which has historically resulted in companies’ balance sheets being leveraged up and higher defaults. Companies are purchasing equities with borrowed money, and this cannot enhance earnings growth in the long run – while it can boost a company’s earnings growth in the short term, it does nothing for productivity.

Perhaps the scariest chart in Tim Bond’s note for investors heavily exposed to high yield is one that plots the global speculative grade default rate against the corporate sector’s borrowing (in relation to profits). There is a very strong relationship between the two variables – when corporate borrowing increases, the default rate follows suit about 18 months later. Corporate borrowing has shot up over the past 12 months, and this suggests that the default rate will rise sharply anytime from this summer onwards.

Higher defaults means wider spreads, and we retain a cautious positioned with regards to credit rating throughout the bond fund range at M&G.

So what does this mean for my fund (the M&G European Corporate Bond Fund)? I have taken the fund shorter duration expecting yields to rise further. Ten year Bund yields have moved from 3.95% at the start of March to 4.23% as I write. This week is likely to be an important one with the US Q1 reporting season getting into full swing. For now I intend to continue to run a short duration position though just like the ECB I’ll be watching the data closely!

In a somewhat timely manner the article in The Economist points to a recent sale of bonds secured upon a pool of mortgages issued by the Kensington Group (the British mortgage group specialising in lending to those individuals with impaired credit profiles). The article points to demand outstripping supply in the bond markets, the relatively low premium demanded by such investors whilst at the same time witnessing a very precarious situation in the US. A mere matter of hours after reading the article on Friday my attention was brought to the 23% fall in Kensington’s share price on the back of a profits warning and the resignation of its CEO John Maltby. The bonds have also suffered but as you’d imagine to a lesser degree than the equity.

Clearly we aren’t in any immediate danger of finding ourselves in a US type scenario. Structural differences between the two property markets mean that UK borrowers remain in a position to re-finance and avoid defaulting on their obligations – house prices in the UK continue to rise strongly, in contrast to the recent US experience. However, the article, along with press reports over the weekend of a 102 year old pensioner being granted a £200k (interest only) buy to let mortgage do highlight the need to keep a close eye on loose lending standards on this side of the Pond too.