We’re hearing rumours that the new French government is about to announce a big rise in the VAT rate, perhaps by 5% (Germany hiked its VAT rate by 3% at the start of this year). This would add a full percent to French inflation. Short dated French inflation linked bonds have rallied relative to nominal bonds as a result. Apart from the impact on price inflation, higher consumption taxes will damage consumer spending. We have seen German retail sales growth turn negative so far this year – the French consumer has been slowly recovering since 2004 and tax hikes put this recovery at risk. We all remember the damage that a Japanese consumption tax hike did that their fragile economy a decade ago. It will be interesting to see just how robust the recent Eurozone strength really is, and also interesting to see how the French public and unions react to this, and other structural reforms from the new right wing government under Nicolas Sarkozy. Are we about to see economic reforms on the same scale as Thatcher’s in the 1980s? Talking of which, if you get the chance to see Andrew Marr’s History of Modern Britain on BBC Two, please watch it – it’s by far the best thing on telly (now The Apprentice has finished anyway). Tuesday’s episode focused on the Thatcher revolution, and the social upheaval that the UK went through – from the 3,000,000+ unemployment rates and industrial unrest at the start of the 80s through to our discovery of consumer credit and the yuppy a few years later. Do the French want to swap a large state and social cohesion, but low levels of growth and high unemployment for a more dynamic, Anglo-Saxon style economy, but one where "there is no such thing as society"? By the look of the election results the answer is "yes" – but as the UK showed, the transition period is exceptionally painful.

1. Technical analysis

You may well disapprove of the theory that lines drawn with a ruler and a pencil on a chart of bond yields can help predict the future, but like it or not, enough people in the bond market have been looking at the 5% level in 10 year US Treasuries to make it a big deal. This marked the support trend line of the bond bull market that had gone back to 1987. The market has broken through this level, opening the way for further significant falls (if you believe in this mumbo jumbo).

2. Convexity selling

Long dated fixed rate mortgages – although less popular now than they were a few years ago – are a big part of the US property market. These are then repackaged as Mortgage Backed Securities (MBS) and sold on to bond portfolios, with cashflows from homeowners (interest payments and capital repayments) flowing through to the bond investors. Unfortunately these bonds have "negative convexity". This means that they perform badly when yields rise, and badly when yields fall – you only outperform government bonds in relatively stable yield environments. Why? Well when yields fall, the homeowner can pay back the mortgage early and remortage at a lower rate. This means that the MBS owner gets repaid, and the duration of his portfolio falls in a rallying market, making him underperform. In a bear market, as we have now, nobody refinances their mortgages as the new rates are higher. This means that the prepayment rate assumed for the investors’ portfolios is too high, and they end up being longer duration than they wanted in a falling market. As a result many will sell bonds to reduce their duration back to the assumed level ("convexity hedging") and a vicious circle can follow.

3. Capitulation

Some well known bond houses and investment banks in the US have publically changed their formerly bullish views on the market. Both PIMCO and Merrill Lynch have reversed their expectations for Fed rate cuts in 2007. Additionally former Fed Chairman Greenspan has today talked about higher bond yields being likely – a couple of months ago he was talking of the "possibility" of a US recession.

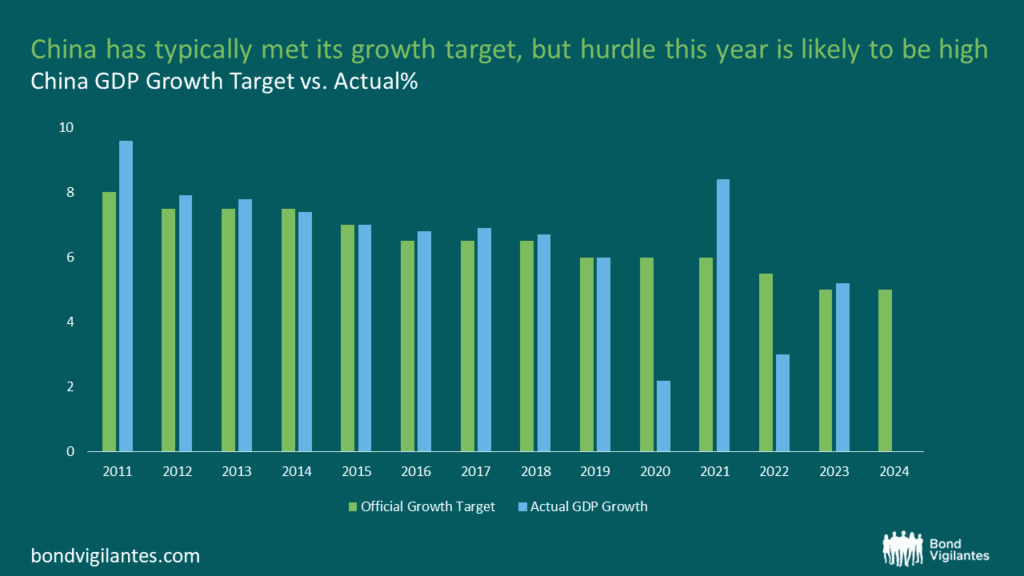

4. China

I talked yesterday about the risk of Asian Central Bank selling of their US Treasury Bond holdings. Well the market’s also worried about Chinese inflation, which has just come in at a 27 month high, albeit at only 3.4%. What really scared markets was the food component, which is rising at over 8% pa (meat and eggs showing 25%+ hikes). With Chinese living standards rising at the same time as biofuel use is raising the costs of crops, is this the start of a global inflationary food trend?

5. The economy, stoopid

US retail sales were very strong today, and economists reckon that second quarter US GDP growth will be back on track after nearly a year of sub-trend growth. Whereas Fed rate cuts were expected earlier this year, the Eurodollar futures strip now prices in a good chance of a hike by the end of this year.

As a result of this demand/supply imbalance, bond yields are very low. Meanwhile equity earnings yields remain reasonably high, spurring companies to releverage. Finance directors with any sense have reacted to the market conditions by issuing debt very cheaply, and buying back their equity. Those that haven’t releveraged have found hungry private equity investors circling their firms. We’ve commented quite a bit about corporate releveraging in our blog (such as here).

Tim Bond believes that foreign exchange reserve growth is prompting global reserve managers to diversify away from low risk bonds and into higher risk assets, and suggests that China will redirect some $300-400bn away from bonds and into equities. Foreign exchange reserves certainly go some way to explaining why bond yields remain so low, but the projections for China appear a little aggressive. The US Treasury publishes this lengthy analysis of foreign ownership of US securities. It shows that overseas investors own more than half of the outstanding US government bond market, up sharply from 22% in 1989. China’s holdings of US Treasuries have risen very steadily from around $80bn at the beginning of 2002 up to $420bn at the end of March, which is second only to Japan’s $612bn. There is little sign of China’s build up of Treasuries slowing, never mind falling back down to 2002 levels, but I agree with the general conclusions of Tim’s article – bond yields have been depressed by significant and continuous Asian central bank buying, but if these foreign buyers stop turning up to the Treasury’s bond auctions this bear market might have further to run.

I see the Chinese buying of US bonds as a form of vendor financing. China produces goods, but doesn’t (yet) have the domestic demand to purchase them. The US consumer has massive demand for goods, but doesn’t have the means to pay for them. So the Chinese give the Americans cheap credit in order for them to keep buying, and keep the Asian factories in business. As long as the current global demand imbalances persist this should keep the US bond market stable. But what happens if Asian domestic demand grows to an extent that they don’t need to rely on the US consumer? Or if European domestic demand finally starts to recover, creating another big market for Asian goods? Finally what about the losses that the Asian central banks are suffering on their US bond portfolios? In this quarter alone so far the Treasury bond market is down 1.2%, so the Chinese will have suffered mark to market losses of $5bn, and the Japanese over $7bn. Might there be a mass running to the door?

Sent by anonymous, 4 June 2007:

As an investment IFA I can sympathise with the question dated 23.05.07 – in relation to asset allocation and the resultant bond exposure so many stochastic modelling tools tell us to have. We have been underweight in Fixed Interest in general as an asset class for about 1 year now and going overweight in UK commercial property funds. This I am now taking back down to neutral (as I think UK property has had its day) – but I am still nervous about increasing the fixed interest exposure. I have looked at funds that use the UCITS III powers ie "strategic" bond funds and have to say that they look exciting. On the flip side however, I read a report that suggests some managers do not have sufficient knowledge to use the derivatives effectively and this could cause a major problem.

I would be interested to hear your views on this topic – particularly in relation to CDS, CDOs and the impact the US sub prime market problems could have on these.

The CDS (Credit Default Swap) market has developed rapidly, and in just a decade is now more liquid than the conventional corporate bond markets. There are undoubted benefits to CDS, namely that derivatives can provide investors with pure exposure to a company’s credit risk (so it doesn’t matter whether interest rates go up or down), and investors can make money from correctly forecasting that a company’s credit worthiness will deteriorate. The development of CDS has also been integral in spreading and diversifying risk within the economy as a whole, although the sheer size of the market has led to concerns.

The biggest worry is whether derivatives can withstand the impact of a large unforeseen shock. By definition, it’s not possible to predict a large unforeseen shock, but all we can say for certain is that there will be one. Last week, Terrence Checki, a vice president at the New York Federal Reserve, warned that "abundant global liquidity has been a powerful wind in the back of economic and policy progress and has bought substantial benefits [but] as we all know, liquidity is ephemeral: it disappears at the most inconvenient times". This is precisely what happened after the Russian default of August 1998, which was the last quake to shake the bond markets.

The Russian default caused financial markets around the world to seize up. Global liquidity evaporated, even for US Treasuries. The sudden and sharp spread widening wreaked havoc on what were supposedly low risk investments. Higher risk investments were inevitably hit hard – between July 20 1998 and October 5 1998, the FTSE 100 fell from 6179 to 4648. Perhaps the highest profile collapse was that of the Long Term Capital Management (LTCM), a hedge fund that lost almost $5bn in a matter of months and had to be bailed out by the Federal Reserve in order to prevent a widespread global meltdown. Now that the derivatives market is many times bigger than in the 1990s, what will the impact be of another Russia?

The problem is that the CDS market hasn’t been properly tested yet, because defaults in the global bond market have been incredibly low for an almost unprecedented period of time. This is not to say there have been no defaults at all though – Delphi, the world’s biggest auto parts manufacturer, defaulted in 2005. Delphi had around $2bn worth of bonds outstanding, but the value of the CDS riding on Delphi was over $20bn. Traditionally in the CDS market, contracts were settled by delivering the actual bonds, so investors that had bought protection needed to go into the market, buy the defaulted bonds, and then sell the bonds at par (100% value) to investors who had written protection. With Delphi there were concerns that the huge number of derivatives would create settlement problems, however a large proportion of the derivatives were either netted off against each other or settled for cash, and settlement in the end proved fairly straightforward. Cash settlement is becoming the norm in the CDS market, and the risk of any major settlement issues cropping up in the future is falling as the market becomes more transparent and efficient.

Moving onto CDOs (Collaterised Debt Obligations), the issues facing CDO investors (specifically synthetic CDO investors) are similar to those facing CDS, because synthetic CDOs are invested in CDS. With a CDO, an investor can choose precisely how much risk they want to take. Someone who invests in an equity tranche faces potentially large rewards but knows that if the portfolio is hit by defaults then they will be the first taking a hit on their capital. An investor in an AAA rated tranche of a CDO knows that he or she won’t lose any money until all the investors ranked beneath them are wiped out. The risk facing CDO investors, though, is knowing how much risk they are actually taking. There’s been a fair amount of criticism directed towards ratings agencies (see here for a good piece from the FT) who, it is argued, aren’t up to the job of rating sophisticated structured products. Does a AAA rated synthetic CDO tranche really carry the same default risk as a US Treasury? We’ll only know for sure when there’s a liquidity crunch.

The woes of the US mortgage market have hit a number of CMOs quite hard (CMOs are like CDOs, except the underlying portfolio is invested in mortgages rather than bonds). We’ve covered the US sub prime mortgage market in a fair bit of depth on this blog (see here, for instance). The yield on a number of CMO tranches that were previously rated investment grade suddenly shot out to 15% once the size of the collapse became apparent, but at the moment, it doesn’t look like the US sub prime crisis is the next Russian default. After pausing for breath, equity markets have more than recovered their losses and jumped to record highs in the US.

Finally, the concern over fund managers’ experience in dealing with products and instruments such as CDOs, CLOs and CDS is certainly a legitimate one. Some asset management firms are able to rely on their experience in alternative assets to build up the necessary operational infrastructure. M&G are lucky to have a market-leading CDO team who have been using CDS for over five years. The use of Value at Risk (VAR) analysis is also critical to control portfolio risk. But it’s less likely to be an operational issue that hurts investors rather than bad judgement from a fund manager. Investors need to be aware that while buying protection is not a risky strategy, since the downside is capped, writing protection has the potential to result in a fairly large loss. Given our views on credit risk in the corporate bond market, Richard Woolnough has mostly used CDS to buy protection in the M&G Optimal Income Fund, since he thinks there are a greater number of unattractively priced corporate bonds out there than attractive ones. When the next Russia comes along, it will likely be those funds taking excessive risk by writing protection on companies whose bonds default that will feel the pain. In short, if you make bad investment decisions using CDS and CDOs you will lose money, just as you would in traditional instruments, but there is nothing intrinsically bad about the derivatives and structured credit markets, and indeed they are often used to reduce and diversify risk rather than increase it.

Being a gloomy bond fund manager, I like nothing more than to read a book predicting economic and social collapse. Thus I’ve just finished reading The Last Oil Shock – a Survival Guide to the Imminent Extinction of Petroleum Man, by David Strahan. There’s not much new in this, but it does contain a useful recap of Peak Oil theory. As a quick summary, Dr M. King Hubbert used statistical sampling techniques to correctly predict the peak in US oil production in 1971, and later, that global oil production would peak in 2005. So we’ve reached the point where oil production is falling, yet global demand is rising by 2-3% per year as emerging market growth develops. The most interesting thing for me in the book was some analysis of the imaginative estimates of reserves produced by the OPEC nations (the true numbers could be half what is stated), and also the assertion that poor stewardship of many oil fields (most obviously in Iraq) has reduced their potential dramatically.

So I was out for a beer with one of my cleverer friends last week, and was on my soapbox proclaiming that it’s not for global warming reasons that we should be saving energy, but because we need to reduce our dependence on fossil fuels before they run out, leaving us in an anarchic Mad Max world. And even if you believe that we’ll muddle through without having to move to the hills and buy shotguns, the impact on inflation of higher and higher oil prices would be significant. He told me not to worry, and to read this article about nuclear fusion. In contrast to fission, in which atoms are split apart to create nuclear reactions, fusion joins hydrogen isotopes together to produce helium, a neutron and energy. This is the same type of reaction that powers the sun. The reaction produces only very low levels of radiation, so its safe, and no CO2, so it’s good for the environment. The problem to date is that the amount of energy required to join the hydrogen isotopes together can exceed what comes out. But this is changing, and there’s a French fusion reactor being built right now, as well as an EU project underway to use lasers to initiate the fusion process. So the prospect of almost free, unlimited, safe and clean energy is not simply a dream, but a real possibility, and within our lifetimes. Free energy, no need to get involved in the Middle East to secure oil supplies, or to be held hostage by Russia over access to natural gas, and no greenhouse gas emissions – could this be the next golden age for mankind?