We have just 17 days to wait till the publication of Alan Greenspan’s autobiography, "The Age of Turbulence: Adventures in a New World". It’s 544 pages long, so hopefully nobody will buy it for me for Christmas, but from the synopsis that’s been released we learn what a great job he did of saving the world:

The most remarkable thing that happened to the world economy after 9/11 was …nothing. What would have once meant a crippling shock to the system was absorbed astonishingly quickly, partly due to the efforts of the then Chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, Alan Greenspan. The post 9/11 global economy is a new and turbulent system – vastly more flexible, resilient, open, self-directing, and fast-changing than it was even twenty years ago.

Events of the last couple of months show that the economy is a little less flexible and resilient than claimed – and many would argue that the huge imbalances in the western economies have resulted from Greenspan’s actions at the Fed. Whilst rates needed to come down post 9/11 and the bursting of the tech bubble, they were then kept at emergency levels for far too long. The Fed Funds rate was kept at 2% or below from September 2001 all the way through to November 2004, yet US growth had recovered significantly by the third quarter of 2003 and was probably well above trend by early 2004. This mispricing of the cost of money simply created another bubble, this time in residential property, as well as increasing the attractiveness of leverage in the financial sector. The unwind has only just begun. Bernanke got the hospital pass, Greenspan got the book deal.

It was announced yesterday that US house prices fell by 3.2% in the year to the end of June, according to the S&P/Case-Shiller house price index. This is the most severe slide since the index began in 1988. It is worth emphasising that this data does not include the turbulence of the past couple of months – things may have deteriorated much further.

We now have a simultaneous attack on economic growth in the US from both the real economy (ie the stalling consumer) and from the financial sector crisis (ie no more cheap money). It looks like the US housing disaster will probably get worse before it gets better, and a US recession is looking more and more probable (50/50 for 2008?).

I am giving a teleconference on Friday 7 September at 10.00am to talk through what’s going on in bond markets and the global economy at the moment. If you are interested in our views and have any questions about recent events then please click here to register for the teleconference (registration now closed).

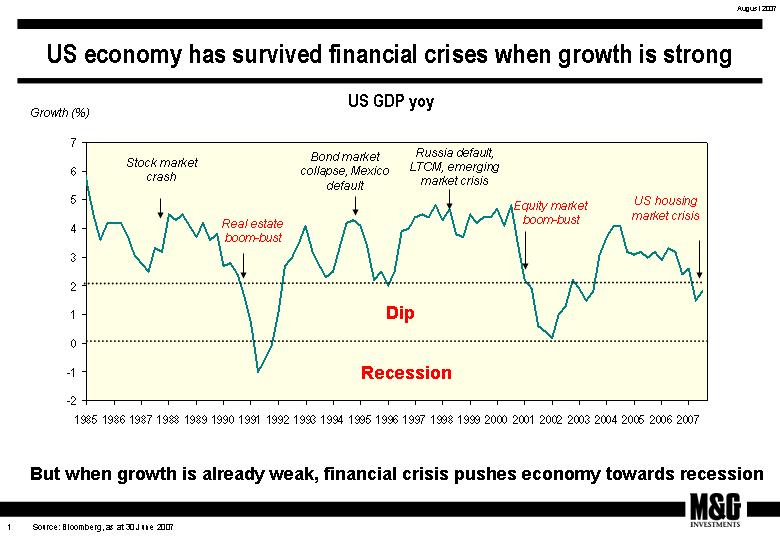

He certainly has a case. This chart plots US economic growth since the mid 1980s, and I have annotated the various financial crises over this period. What is striking is that when a financial crises occurs during times of rapid growth, the economy dips a little but quickly bounces back. In fact the US economy didn’t waver at all following the stock market crash of 1987, probably because US growth was booming at an annualised rate of 7.2% in Q4 1987. The financial crises of the mid-late 1990s only caused the US economy to dip briefly.

He certainly has a case. This chart plots US economic growth since the mid 1980s, and I have annotated the various financial crises over this period. What is striking is that when a financial crises occurs during times of rapid growth, the economy dips a little but quickly bounces back. In fact the US economy didn’t waver at all following the stock market crash of 1987, probably because US growth was booming at an annualised rate of 7.2% in Q4 1987. The financial crises of the mid-late 1990s only caused the US economy to dip briefly.

But a financial crisis combined with already-weak economic growth has traditionally caused a severe dip. The real estate boom of the late 1980s turned to bust, and helped contribute to a sharp recession in 1991. The equity market collapse of 2000-02 occurred when the economy was already on its knees, and only some aggressive intervention from the Fed and the US government prevented the US economy experiencing negative growth.

This time around, the US economy has already had a year of sub trend growth, and a credit crunch has come at a bad time. I think the Fed will have to act fast to prevent a slide towards recession.

Unemployment in the US has remained remarkably low in the face of the recent economic slowdown, partly because unemployment has traditionally been a lagging indicator. Labour market rigidity means it’s not possible to immediately make workers redundant when there’s a slump in demand (even in the hire & fire US economy).

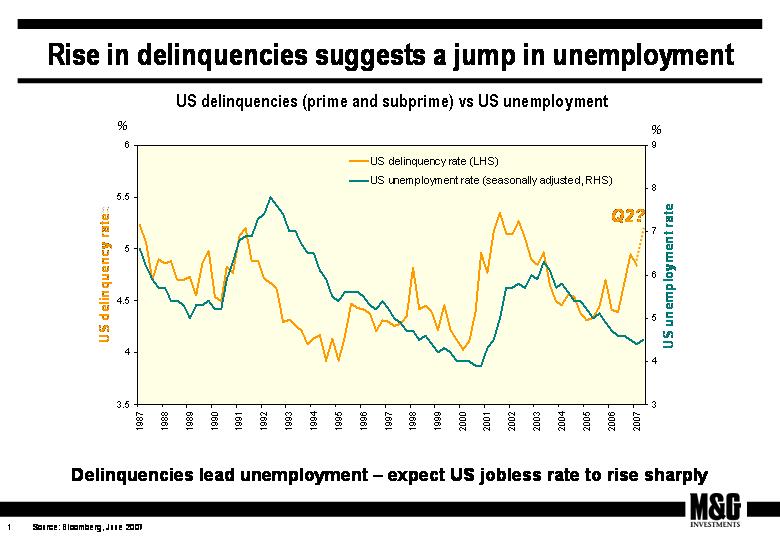

But the unemployment rate looks finally set to turn. US initial jobless claims moved higher for the third consecutive week last week, and this chart suggests that a jump in the unemployment rate is imminent. There is a close correlation between the US delinquency rate and the US unemployment rate, where delinquencies tend to lead unemployment by about two years. Most worryingly, the delinquency data here is only for Q1 this year – Q2 figures aren’t due to be released for a few weeks yet, and will surely be significantly higher.

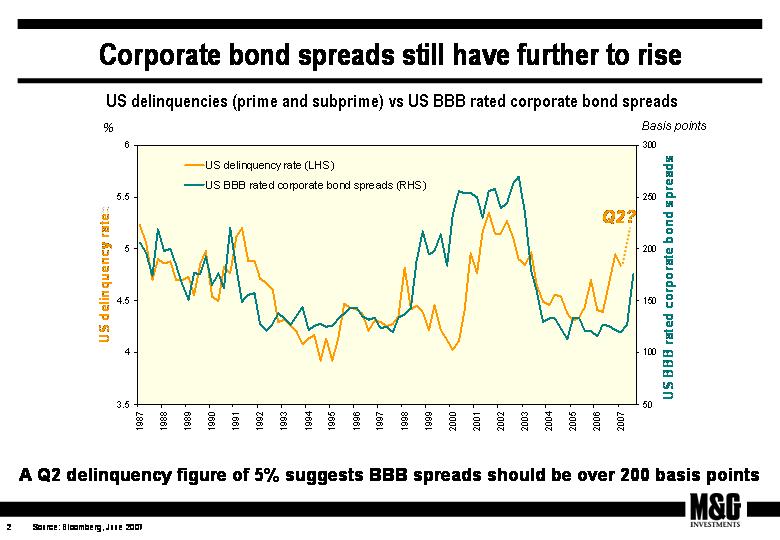

In fact you can plot the delinquency rate against a number of other variables, and all make fairly grim reading. This chart shows the correlation between delinquencies and corporate bond spreads. The corporate bond sell off that’s taken place over the past couple of months should have been of no surprise given the recent spike in delinquencies, and if you assume that the Q2 delinquency figure will be in the region of 5%, then the spread on the average US BBB rated should be over 200 basis points, not the 177 basis points at Friday’s close.

Last week saw some dire statistics released on US housing starts, permits and completions. US builder sentiment is close to all-time lows, and the housing market debacle is far from reaching the bottom.

What assets have performed well over the past month? Not surprisingly, assets with a lot of duration have had an incredible run as interest rate expectations have been pulled down sharply. Long dated gilts have returned over 5% in the last month, although year to date returns are still in negative territory. Interestingly, though, the dramatic spread widening of the past month has meant that long dated corporate bonds have hugely underperformed, returning just 2%. Long dated financials have performed particularly poorly on sub prime concerns, returning just 1%.

In line with this, I remain very cautious with regards to credit risk, and much prefer holding long dated AAA assets such as gilts and supranationals to get duration exposure. The market expects US interest rates to bottom out at 4.5% early next year, but history suggests the Fed tends to act very aggressively in the face of an economic slowdown. In the last two rate cutting cycles, it slashed rates from 9.75% to 3% in 1989-1992, and from 6.5% to 1% in 2000-2003.

Back in April I wrote that I believed the European Central Bank (ECB) would take its key interest rate beyond 3.75% to 4% and potentially beyond (see here). The ECB did indeed hike to 4% in June, where we currently stand, and pre-warned in early August that they would likely move to 4.25% at their September meeting.

However, the recent volatility and economic data have market participants questioning either the likelihood or indeed requirement for a hike come September. Whilst the futures market is still implying a very high likelihood of a hike, I believe the ultimate outcome is more balanced. Though if you pushed me into a corner I’d agree we will probably see the ECB move to 4.25% and stop.

On the one hand the ECB believes that it must target inflation risks over the medium term to ensure price stability and that the risks remain to the upside. Also liquidity (at least until recently) has remained high and interest rates are not in the ECB’s mind, as yet, in restrictive territory. Furthermore, capacity utilization in the Euro zone continues to remain at historically high levels. However, the ECB can’t ignore the recent re-pricing of risk (albeit they have been trying for some time to remove liquidity to prevent asset bubbles), the loss of confidence by some and the obvious pain felt by many. Infact the ECB have been very active in recent days, injecting funds to try and calm the short term commercial paper and overnight deposit markets. Furthermore the ECB will also have to take into account the recent slowdown in GDP (from an annualised rate of 2.5% to 3.1% in Q2).

The likelihood of an emergency cut from the Fed has been much touted of late. I’m not suggesting that Fed policy will dictate to the ECB, however, if we were to see Fed cuts then the ECB may find it that bit more difficult to hike.

So what does all this mean for the European Corporate Bond Fund? I decided last week to begin reducing my short duration position and am targeting a flat duration position for now. As ever, I’ll be keeping a close eye as events unfold.

Rather ironically, a Canadian investment company called Coventree has been ostracised by investors, and (almost) literally “sent to Coventry“. Coventree Inc, which specialises in structured credit, saw its share price fall by 32% on Monday and by 72% yesterday after the recent credit crunch meant that it was unable to refinance C$700m (about £330m) of maturing debt. After failing to refinance the debt, Coventree went to lenders requesting additional loans, but was initially shunned. In a press release, the company said that “certain liquidity providers have advanced funding, some have disagreed that they have an obligation to fund, some are in discussions with the company, and some have not responded”.

The company did yesterday eventually manage to place C$600m, but warned that there are no assurances that it will be able to keep issuing ABS and there is a risk of default. DBRS, a Canadian credit rating firm, said that 17 issuers of ABS are also seeking to raise cash, and their failure to receive funding could result in defaults on outstanding paper.

This is a good example of contagion – what was initially just a US sub prime issue is spreading across borders and is hitting firms that aren’t necessarily connected with sub prime. If companies can no longer finance their long term liabilities with short term funding, then implications for the credit market remain significant despite recent intervention from central banks.

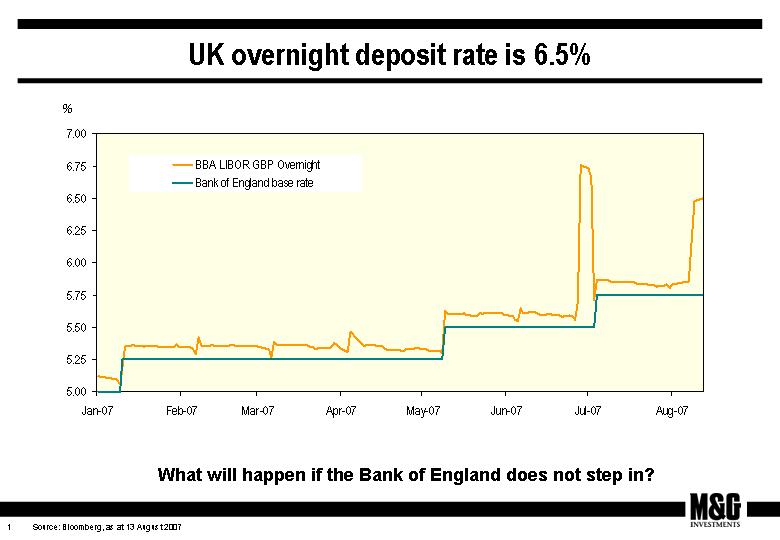

Following on from my comment on Friday, it’s interesting to note that the Bank of England has so far refused to pump liquidity (Ooh matron) into the UK money markets, and as a result, the UK overnight interest rate is currently 6.5%.

Mervyn King (who is one of the hawks in the MPC) last week said that credit turmoil might be a good thing if it persuaded investors to take a more realistic view of risk, and denied that there is currently an international financial crisis. He may be right, but if the overnight deposit rate remains at 6.5% rather than 5.75%, then monetary policy will in effect be much tighter than the Bank of England has intended.

The European Central Bank’s (ECB) job is to set the target interest rate (currently 4%) and then ensure that the market rate (as dictated by banks) does not deviate too far from this. As the attached chart shows, the market rate soared to 0.6% above the target rate yesterday, and the ECB yesterday responded to the credit crunch by injecting almost €95bn of liquidity in to money markets. It’s not unusual for the central bank to intervene in the money markets, but this was the largest intervention since the terrorist attacks on the twin towers. The Federal Reserve also intervened after the US overnight rate reached 6%, way above the Fed’s 5.25% target rate.

Why has liquidity dried up? There have been a series of high profile failures of US hedge funds and European asset backed funds, which has increased end investor and bank nervousness. This has resulted in a less liquid money market, hence reducing money supply, which has pushed rates higher and has forced central banks into action.

The big question is whether this market action is temporary, or whether liquidity needs to be provided on a longer term basis. If the latter, then one can expect rates around the world to start to fall, and for the bear market in government bonds to come to an end.

Jim Cramer of CNBC redefines hysteria, from about two minutes in (click here to watch). Enjoy.