Financial markets can be a scary place for investors. The US economy is now in its longest expansion on record, the world is seeing record level of total debt and now even some corporate bonds have negative yields.

If you’ve carved a pumpkin, got your Halloween costume and been to see the latest scary movie, there’s only one thing left to do: take a look at the Bond Vigilantes team’s 2019 Scary Charts.

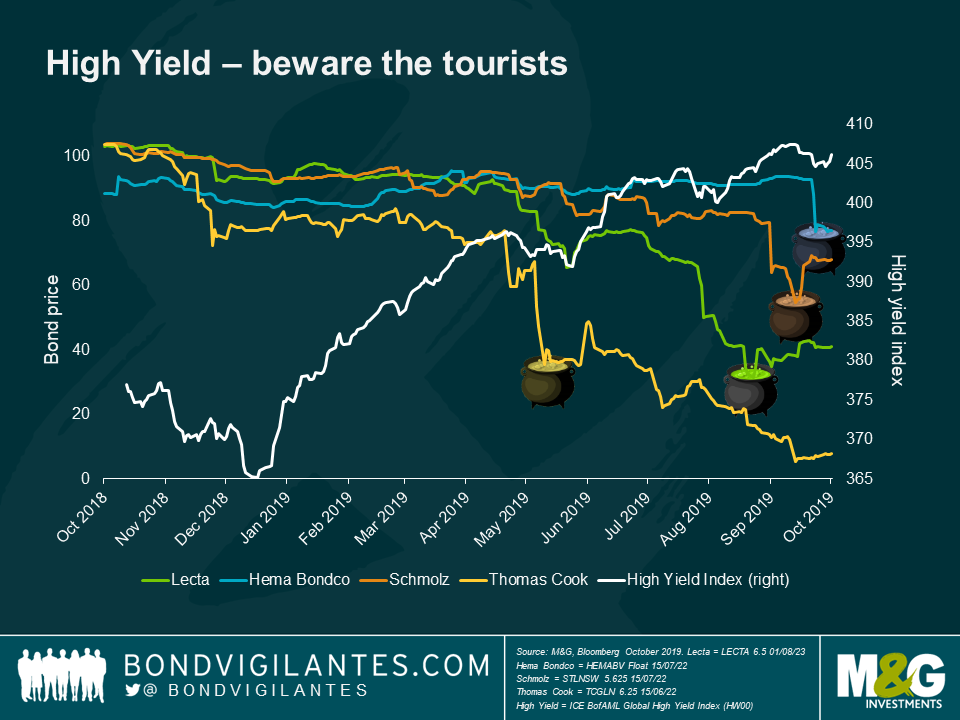

If you’re searching for some decent yield right now, high yield must be a good place to start, right? Year-to-date, investors have seen double-digit returns in high yield: around 12% and 9% in the US and EU index respectively. In our yield-deprived time, many who would normally be holding investment grade bonds have been willing to sacrifice credit quality and take a trip into high yield.

But watch out: when there has been the slightest sign of trouble in some large household names this year, these high yield tourists have wanted out at any price. Some high yield bonds have taken a plunge this year, even where the bonds have not defaulted.

So if you’re dipping your toes into high yield, make sure it’s based on a deep understanding of issuers and that there’s nothing lurking in the depths…

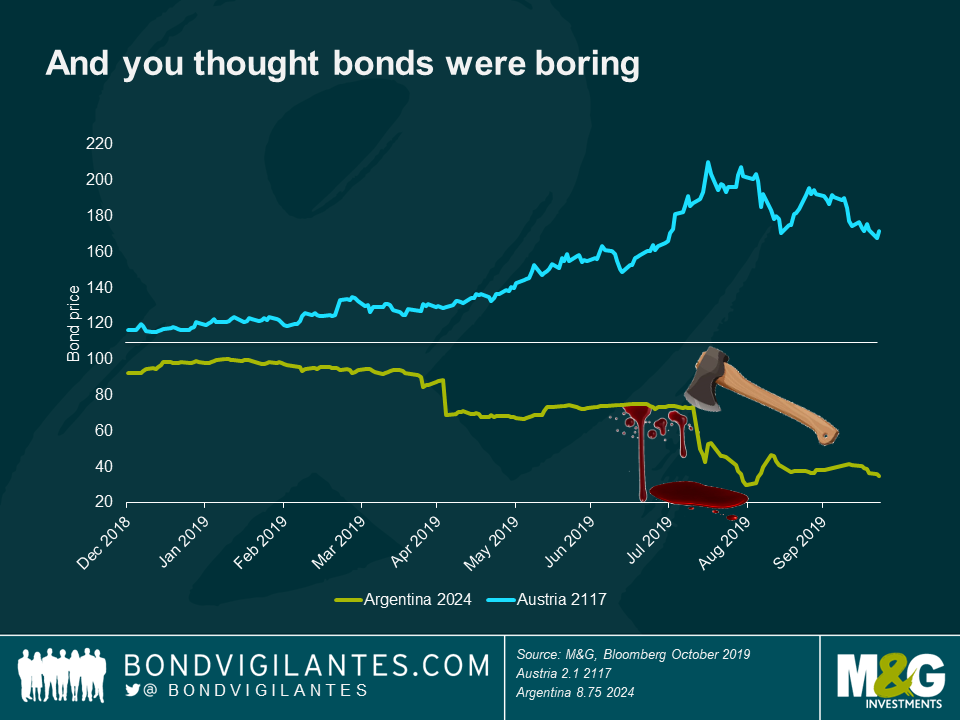

If you thought that bonds were the safe and boring part of your portfolio, think again. Take a look at these two bonds, the Argentina 8.75% 2024 and Austria 2.1% 2117.

After Argentina’s relatively market-friendly President Macri was trounced in the primary elections by populist Fernandez, Argentinian bonds were decapitated, with more than half their value chopped off. They now trade at around $40 per $100 par value.

Meanwhile, investors in Austria’s AA-rated 2117 bond this year will be patting themselves on the back for the trade of a lifetime. With a duration of over 50 years, downward pressure on bond yields this year saw the bond almost double in value.

Looking at European and US IG credit, trade wars clearly scared markets earlier this year. But the sell offs are getting smaller. It looks like the market may be suffering from trade war fatigue after so many headlines and tweets over the past few months. But might trade wars come back to spook the markets even further?

According to political hearsay, Democrat front-runner Elizabeth Warren is even more ferocious on trade than Donald Trump. She has also been called “the monopolist’s worst nightmare” due to her criticism of big tech companies, a large constituent of the US IG index. Although the 2020 elections seem a long way off, success for the Democrats may cause some ripples for markets.

While current IMF figures estimate that the US-China trade war has shaved 0.8% from global growth, with 0.5% added back by global monetary easing, could even more protectionism and larger potential tariffs in the future leave investors wishing for the days of Trump?

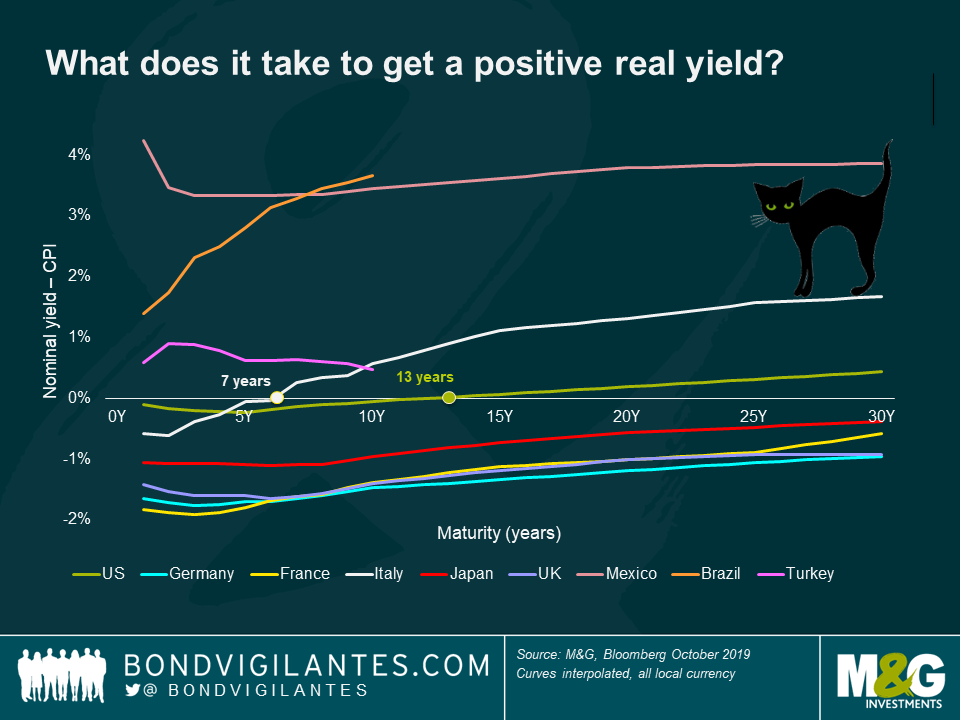

Equities are for growth and bonds for income, right? Not in Germany, France, Japan and the UK, where real yields are negative even up to 30 years. In Italy you need to invest for seven years to get a positive real yield.

No wonder investors are looking to emerging market debt in search of yield. Brazil and Mexico provide positive real yields, as does Turkey – but beware an upside surprise to inflation.

This is a scary measure of how far investors are being pushed just to get a positive yield.

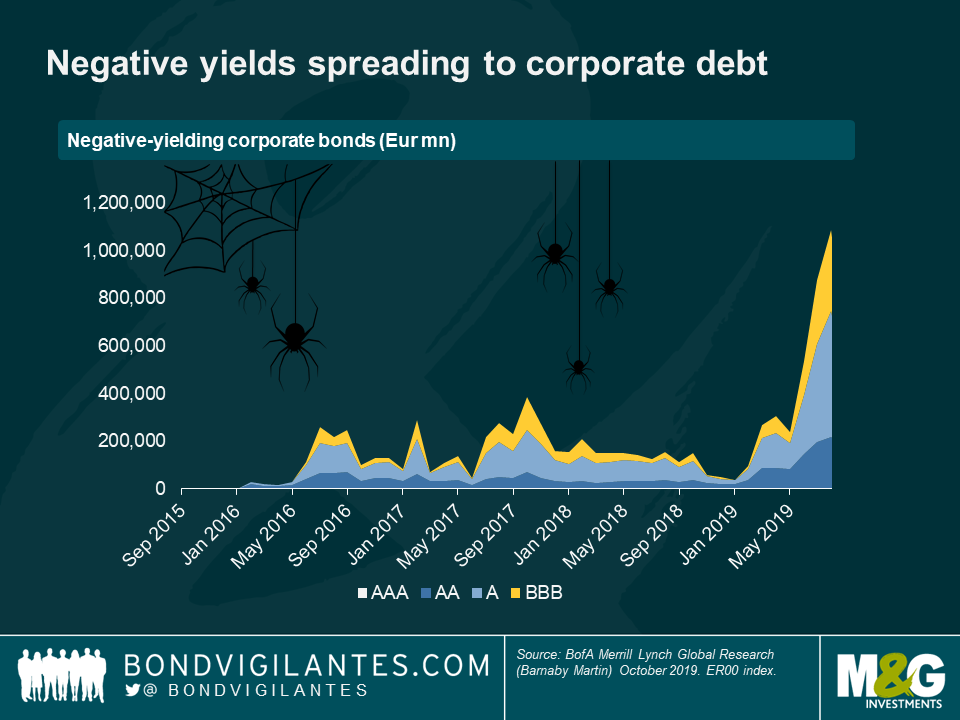

If you’ve seen enough negative-yielding government debt by now not to be spooked by it, take a look at this next chart.

Even many corporate bonds are now negative yielding. This chart shows the face value of negative-yielding debt in the ICE BofAML Euro Corporate index: now as high as €1 trillion!

Most of this negative-yielding corporate debt is actually in the lower end of investment grade, namely A and BBB.

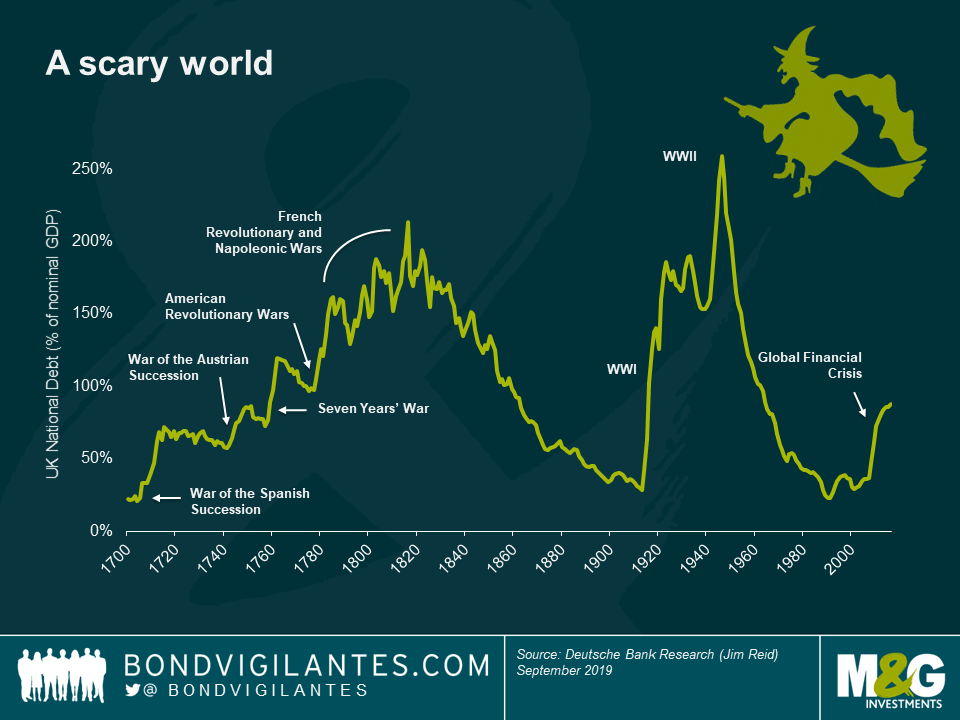

Here’s a scary statistic: total (public + private) debt in the world has never been higher. And looking at public debt alone, while its peak could be seen during and after the Second World War, government borrowing is at its highest peacetime level.

Taking UK debt as an example, a spike in borrowings can be seen since the 1700s whenever financing was required for a war or conflict. So what is going on now to explain the spike in government borrowing?

One answer may be the greater power of democracy in the world. In order to pay down its debt, a country must maintain a primary surplus. Put simply, it must raise more revenues through taxation than it spends on citizens. While governments in the past had the power to do this, who would vote to be subject to such an environment for long? We have seen the rise of populism in countries like Italy which have tried to move from deficit to surplus.

Governments and central banks have a scary problem in trying to keep public debt under control in this new world.

Happy Halloween!

No doubt the main thing that Mario Draghi will be remembered for is his famous “whatever it takes”. He told financial markets that the Eurozone was not about to collapse and made it clear that the ECB would save the banks and peripheral sovereign nations of Europe.

More interestingly, however, is to think about how Draghi found himself in the position to be able to QE and to undertake other exceptional monetary policy actions in the face of quite severe opposition, especially from countries like Germany.

When we look at the Eurozone crisis we must remember that by then the euro currency itself was just over 10 years old. The first two ECB presidents, Wim Duisenberg and Jean-Claude Trichet, with their Northern European mindsets, had established the Eurozone currency area’s credibility. In the case of Trichet, this inflation hawkishness had led to the ECB making the biggest policy mistake of its young history, in hiking rates in the midst of the Global Financial Crisis.

So when Draghi, with his Southern European mindset took over, the eurozone was already established as a credible currency area. And more importantly, it had already experienced hawkish policy errors. If the eurozone crisis had happened shortly after 1999, I expect that the currency block would have disintegrated. So Trichet’s failures allowed Draghi to experiment. And in the absence of fiscal policy coordination, and with markets punishing profligate borrowers, it was entirely left to monetary policy to do the economic heavy lifting.

So the ECB and Draghi did save the eurozone, but at what cost? Well, we now have too many “zombie” banks and companies in Europe, used to cheap money, and this will depress future growth. And we also know that QE has diminishing returns as central banks do more of it, so the incoming Christine Lagarde will find that more bond buying will have less bang for the buck.

But history will be kind to Mario Draghi – in a world where politicians refused to save the eurozone through fiscal redistribution, he did “whatever it took”. It wasn’t perfect, but it was the best we had.

2019 has been a pleasant ride so far for high yield investors. Over the past 9 months the global high yield market has delivered a total return of 10.9% and an excess return of 6.4%, in part thanks to the U-turn of major central banks. Despite all the good news, things have occasionally gone wrong.

Recent events have reminded high yield investors that investing doesn’t come without risk. Thomas Cook, the UK tour operator, was grounded after final restructuring negotiations failed. To blame Brexit or the slowdown in global growth for the default would be a hasty conclusion. The business, operating in a structurally challenged industry, had long stretched its financials to the limits. The fragile situation did not go unnoticed by customers, who had stopped booking with the business. As a result of this, 2018 EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation) dropped by 14.6% year-on-year which also changed the ability to materially generate positive cash flow. The company produced a negative free cash flow of £148 million in 2018. 2019 half year numbers revealed an even worse picture, with a seasonal outflow of £839 million; £121 million higher than the previous year. Operating with current liabilities that exceeded current assets by £2bn, made the solvency issue even more pressing and, in the end, didn’t allow the company to recover in time. This is a prime example of how quickly things can fall apart if consumers lose trust in a business. With bonds trading currently at 7 cents in the euro, investors only foresee a limited recovery rate for the asset-light business, which is also carrying a large amount of debt structurally senior to the bonds.

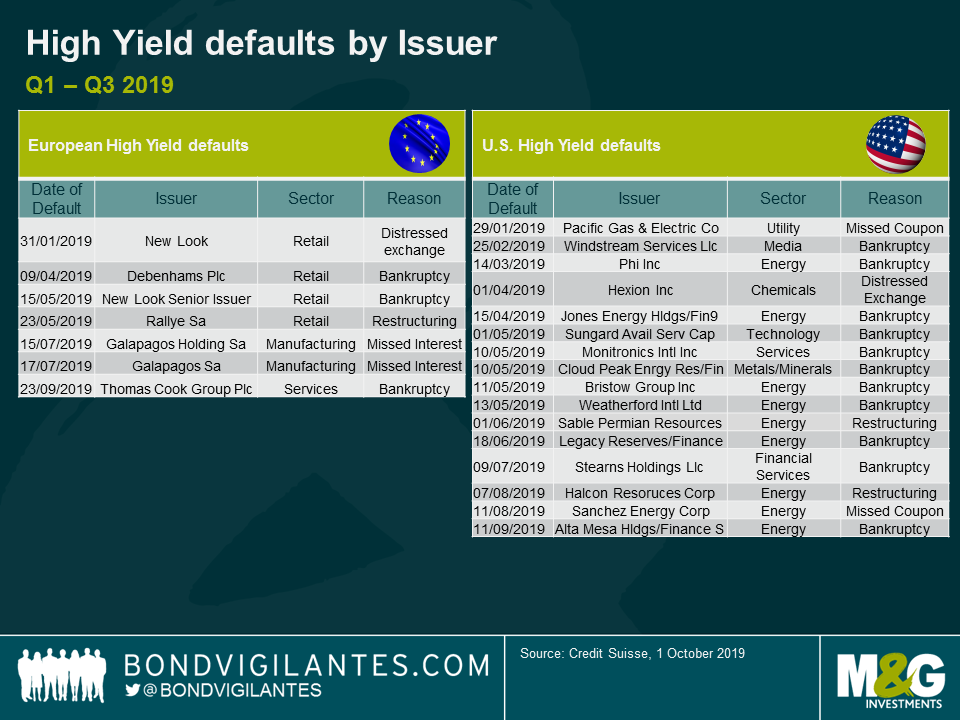

Thankfully, these default cases are the exception rather than the rule and we’ve only seen a handful of defaults in Europe this year. Early on in the year, the Retail space made headlines. It was high street retailer New Look who had to capitulate after net leverage skyrocketed well into the double digit region following weak Christmas trading. Shortly after, UK department store Debenhams announced restructuring after a period of operational underperformance combined with structural issues. Debenhams was disproportionately hit by the structural shift to online shopping, given its long-term rents and large store estate hindered the retailer from adopting quickly to the new shopping behaviour that resulted in less footfall.

Rallye, the holding company that effectively controls French food retailer Casino Guichard-Perrachon SA, pushed the Retail default rate up by one. Having sold most non-core assets over the past several years, the core investment of Rallye has been Casino. Rallye started to look insolvent as the Casino share priced dropped, and Rallye debt is now being restructured. This is an important reminder for bond investors to consider the additional risks of lending to a holding company, particularly if it only has one income stream.

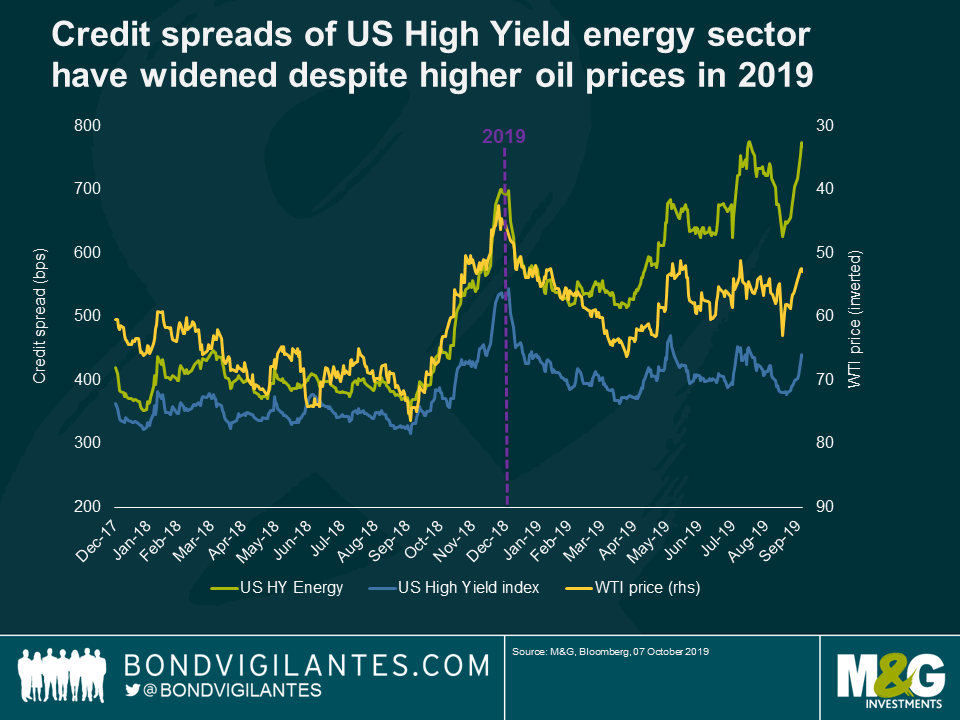

In the US, the Energy sector has been the dominant sector of defaults in 2019, accounting for more than half of the defaulted universe. In fact, the energy sector was the bottom performer in the US high yield market in the first 3 quarters of 2019 delivering an excess return of -2.9%. While the sector is up by 2.5% in total return terms, this makes dull reading compared to the broad US high yield market which generated a return of 11.5% over the same period. In contrast to the wider HY market, credit spreads of the energy sector have actually widened, which might come as a surprise considering that WTI (West Texas Intermediate) is up 17% since the turn of the year, now trading in the mid-50s and above breakeven levels for many oil players. So what is behind the underperformance and defaults in this space?

One part of the answer is execution risk, which was also the source of trouble for Alta Mesa, the recent default victim in the US HY market. The company’s acreage turned out to be less robust than anticipated. In addition, the company was having technical difficulties in drilling their wells, a problem that has already befallen several drillers operating in emerging shale basins across the states. For companies with a single asset exposure, this can be fatal. Bond investors need to carefully weight up whether the low entry costs compared to more established drilling areas such as the Permian basin, are worth the risk of missing production forecasts and consequently the failure to generate the cash flow needed to service its bonds.

As always, a major concern of US Exploration and Production companies is the degree of debt that some players are saddled with, making it impossible to grow into their capital structure should production levels disappoint due to operational issues even when WTI is in the 50’s.

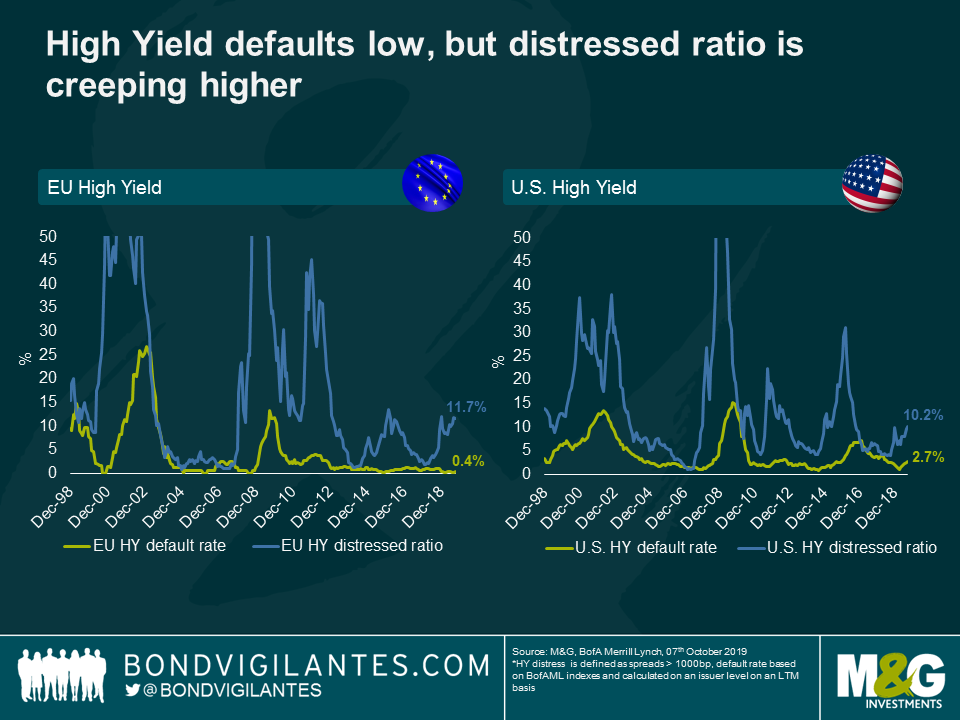

Overall however – particularly outside the Energy and Retail space – defaults remain low in high yield. That being said, the portion of bonds trading at distressed levels, defined by a spread level higher than 1000bps, is on the rise, which tends to be a good leading indicator for future defaults. Therefore, I would expect default rates to increase somewhat from here due to idiosyncratic issues, such as those experienced by Thomas Cook. Bond investors are currently witnessing an increasingly two-tier market. Those that are in favour can borrow cheaply and benefit from the low interest rate environment. Those falling out of favour find themselves locked out of the market with market concerns perpetuating a vicious cycle.