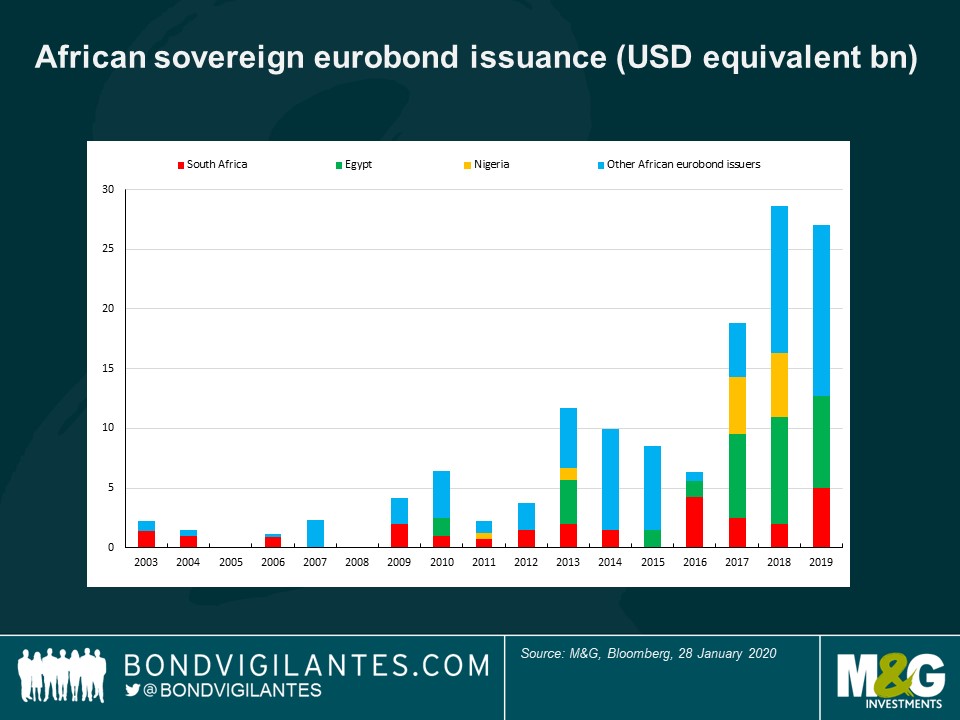

There has been a wave of African eurobond issuance over the past decade. South Africa started the eurobond trend for the continent in 1995, but it has only been since the global financial crisis that push and pull factors have encouraged broader African issuance.

The asset class has grown to 21 African countries with outstanding sovereign eurobonds, totalling $115 billion. This follows a big increase in issuance since 2017, led by the eurobond heavyweights: Egypt, Nigeria and South Africa. The larger economies have been followed by eurobond middle-weights: Ivory Coast, Angola, Kenya and Ghana; who have been extending their curves over the past three years.

The issuance has been mainly in USD, but EUR issuance has become more common since 2018, especially for countries with close trade links to Europe (Morocco and Tunisia) or with currencies pegged to the euro (Ivory Coast, Senegal and Benin). Longer maturities are also becoming more common. Five-years ago most eurobonds were issued with maturities of around 10-years, with a few exceptions from sovereigns who had longer issuance track-records, such as South Africa. But since Nigeria successfully tested the market with 30-year paper in November 2017, Ivory Coast, Ghana, Kenya, Angola, Egypt and Senegal have all come to market with 30-year paper.

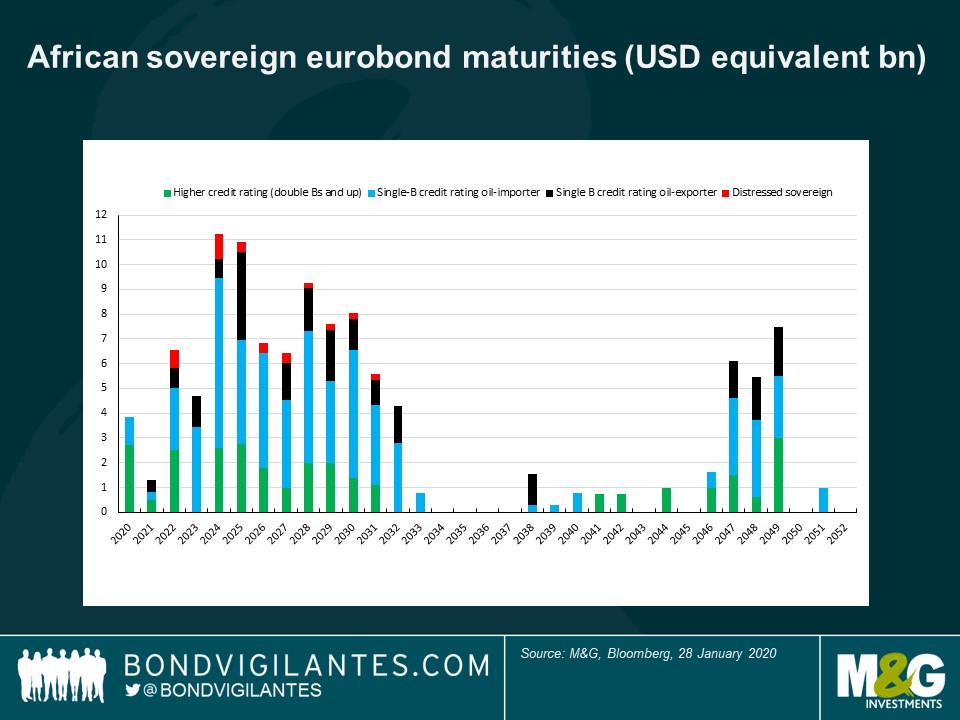

Annual issuance was small before 2013, hence there are not many African eurobonds maturing between now and 2023. But given larger issuance from then, of mainly 10-year paper, there is a spike of maturities coming in 2024 and 2025, creating a wall of sovereign debt repayments.

How worried should we be about this wall of eurobond debt?

African eurobonds and other frontier markets offer higher yields than the emerging market norm, but investors need to be mindful of the increased risks. A specific concern is whether a spike in African maturities in 2024 and 2025 will overwhelm the sovereigns’ ability to refinance their bonds, especially if sentiment towards emerging market is weak in these years.

The wall of repayment is of concern, but three factors suggest there could be more resilience than some of the more gloomy takes on African indebtedness have suggested. First, there is a growing number of African countries who have now repaid eurobonds. Second, there have been few recent events of default. Third, African countries’ debt management is improving. It is becoming less passive and more active.

Growing repayment record

There is a well told story of Africa’s debut eurobond issues of the past 10 years, but less attention is given to a growing record of repayment. South Africa, Morocco, Tunisia, and Egypt each have a growing track-record of repayment. But other countries have also now repaid sovereign eurobonds, including: Gabon, Ghana, Kenya, and Nigeria.

Few eurobond defaults

To date only a few African countries have defaulted on sovereign eurobonds. Including the Seychelles (in 2008) and Mozambique (in 2017), who both later exchanged new eurobonds with bondholders. Also Ivory Coast did not pay coupons in 2011 following post-election violence, but did later reimburse investors for the missed coupons. Since these events, Ivory Coast and Seychelles have developed much better economic and debt management practices. It is hoped Mozambique works to do the same.

It should be noted that the context for the defaults during the African debt crisis of the 1980s and 1990s was very different, as debt stocks were then predominately official. There had been sizeable commercial bank lending to Ivory Coast, Morocco and Nigeria in the 1970s (who like Latin American countries received Brady plan support). But for most African countries, commercial debt was by and large linked to bilateral export credit agreements, later replaced by multilateral lending.

Active debt management

Active debt management is becoming common among African countries. It is important because a $750 million eurobond does not sound large when compared to issuance across emerging markets, but that amount is large relative to the size of many African frontier economies. Further, some African sovereigns are yet to establish a track-record in the markets (this comes with regular repayment and not just regular issuance). Hence there would be concern if some of the African issuers were waiting right until their bonds’ maturities to refinance them. To avoid such heightened repayment risks African countries are increasingly coming back to the market with dual narratives. They are raising money for their budgets and for liquidity management.

Gabon and Ghana came early to the eurobond market in 2007, but ahead of maturities in 2017 they came to the market and tendered some of their debut eurobonds, reducing the repayment risk. More recently Ivory Coast and Senegal followed this trend, reducing some of their shorter dated eurobonds with proceeds from new issuance. Also Kenya repaid one of its debut eurobonds due in 2019 plus syndicated loans, using issuance from earlier that year. Another approach is to save hard currency in a sinking fund, as Namibia has done to prepare for its debut eurobond maturing in 2021.

With this trend of more active debt management it appears like the wall of debt in 2024 and 2025 can be slowly picked apart, with the spikes in maturity being smoothed out. Risks are being spread out over subsequent years and a more positive view of the asset class now makes sense. Debt slips over the next five to seven years appear more likely to be country specific, rather than following a systematic hit to the continent’s debt. This suggests that navigating country-by-country risk is essential.

Monitoring country vulnerabilities

There are a few important things to look out for. First, are build-ups of China’s official lending, as such debt currently falls outside the Paris Club structures for creditor reporting and restructuring (for example Angola, Ethiopia and Kenya among eurobond issuers are particularly exposed). Second, unsustainable debts of state owned enterprises hitting the sovereign balance sheets (for example in South Africa where the electricity utility Eskom is running huge debts). Third, collateralized lending from commodity traders (for example Angola and Republic of Congo have oil-backed debts). And finally where countries are complacent and ignoring the debt alarm bells (Zambia sits in this camp).

Italy currently has a “yellow-red” government

Conte is the Prime Minister supported by 5 Star Movement (yellow) and the left party (red). Prior to this government there was a “yellow-blue” government led by Conte and supported by 5 Star movement (yellow) and the right party with Salvini (blue).

Over the last couple of years there have been 2 significant changes

- The right-wing parties doubled their consensus: Lega (with Salvini) went from just above 15% to just above 30% and it is now by far the biggest party in Italy. Fratelli d’Italia, which is allied with Lega, also doubled its consensus results going from 5% to 10%.

- 5 Star Movement seems to have collapsed: they went from being the first party to now have only 15% consensus and they are still falling in the most recent polls. In addition to this, last week Luigi Di Maio (their leader) resigned.

Here is a snapshot of the opinion polls in Italy (from March 2018 until today):

What happened yesterday?

Yesterday we had regional elections in Emilia Romagna and Calabria. The former was crucial for the stability of the current Government as Emilia Romagna is a big region and has been historically dominated by the left party. A Salvini win here could have created a big challenge for the already very fragile “yellow-red” Government and an higher probability of early elections. This didn’t happen: the left coalition won with 51% votes vs 44% of Lega.

My takeaway from yesterday

While the result in Emilia Romagna has been seen as positive by the market as it decreased the probability of early elections, the current Government remains fragile and unlikely to continue as it is until the next general election (which is in 2023). I say this because:

- Salvini continues to gain consensus: while it is true Lega lost in Emilia Romagna, they managed to get 44% of the votes in a region which has long been stronghold of the Italian Communist Party! Moreover, towards the end of last year Salvini won (by far) in Umbria, a region which historically has been led by the left party

- The 5 star movement is losing its strength and yesterday’s regional elections confirmed this trend: in Emilia Romagna they got less than 5% and in Calabria they went from being the most voted party in 2018 to not even have enough votes to enter in the Regional Council. On the other hand, Salvini undoubtedly won in Calabria.

- Fratelli D’Italia, which is allied with Salvini, continues to gain popularity: yesterday’s elections confirmed this trend

Valuations

2 considerations:

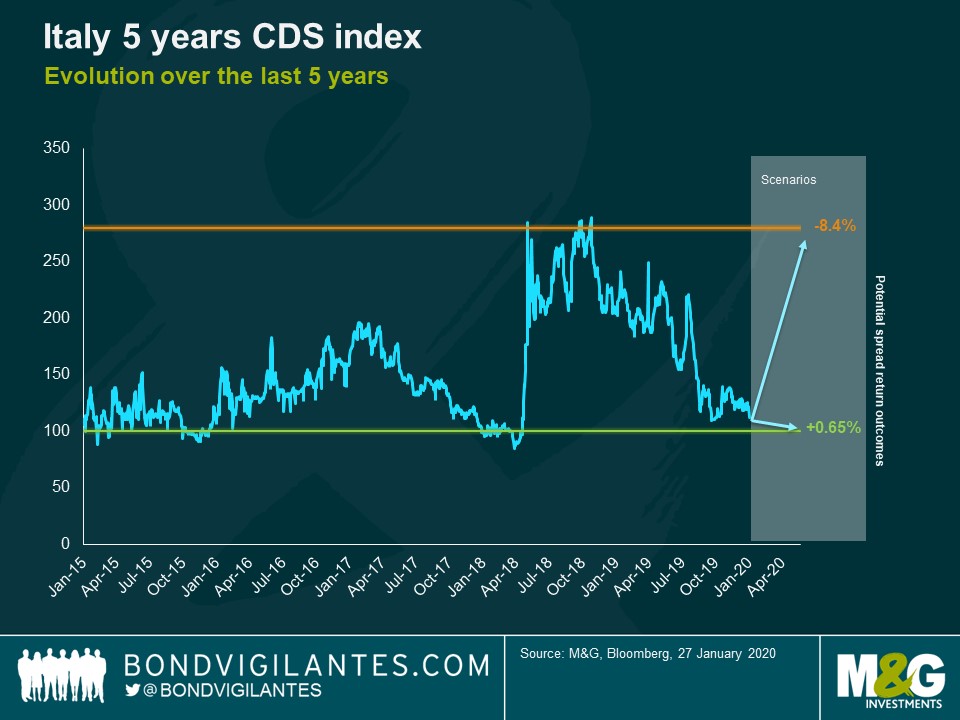

1. Spreads tighten a bit this morning on the back of yesterdays’ results. Currently the ITA 5y CDS is trading with a spread of 113bp: this is very close to the low range of the last 5 years (see chart below) and quite far from the highs of last year. If spreads were to reach the low range levels (100bp), the 5y CDS could return +0.65%. On the contrary, if spreads move back close to the highs seen last year, the index could lose north of 8%.

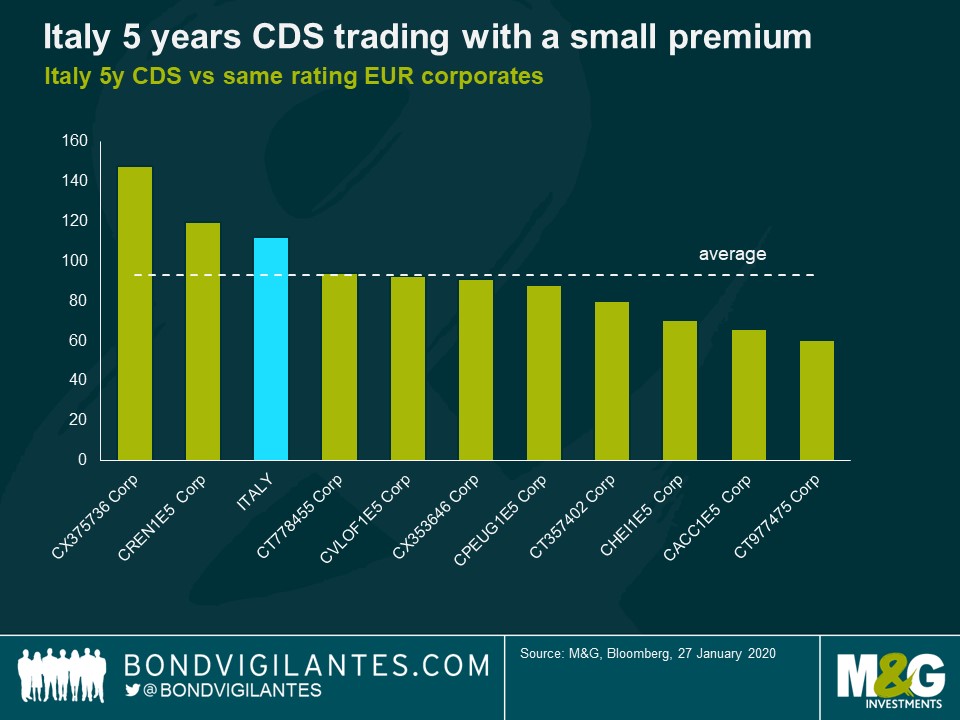

2. Italy is rated BBB- by Moody’s. When compared to other 5y CDS names with the same rating, Italy seems to pay a little premium: currently trading 20bp above average BBB- (see below)

Yesterday’s results were a small positive for credit spreads, but they don’t change the trend we have seen over the last couple of years. The current government will remain under pressure from the rising popularity of the right party on one side and from the fall of the 5 Star movement on the other side. Currently Italian bonds are trading with a little premium, but the market is not fully pricing in the political risk.

A version of this article originally appeared in the Financial Times last week.

There is a widespread assumption that the European Central Bank — like other major central banks — has reached the limits of monetary policy, and that the best we can hope for with Christine Lagarde’s reign is political astuteness in cajoling reluctant politicians to embrace a fiscal stimulus.

This is not the case.

As Ms Lagarde prepares to launch a strategic review of the ECB’s policies and objectives, she has a final item left in the toolkit: dual interest rates.

In practice, this entails the central bank targeting different interest rates for loans and deposits. Such loans can also be restricted to specific sectors, such as renewable energy. The policy would be more effective than quantitative easing, forward guidance or negative interest rates. It would provide a powerful monetary stimulus and could be used to turbo-charge Europe’s Green Deal.

The effects of dual interest rates are easiest to understand in contrast to standard policy. Typically, when a central bank reduces interest rates we expect this to boost spending in the economy through three basic effects:

- Interest rates fall for households with mortgages;

- asset prices rise, making people feel wealthier; and

- the cost of borrowing for companies falls, which should boost investment spending.

But serious problems emerge when interest rates are very low or negative. The interest income which savers receive collapses — weighing on spending — and bank profitability is damaged, causing many unintended consequences.

The application of dual interest rates

What would happen if the central bank raised the interest rate on deposits, and cut the interest rate on loans? Both savers and borrowers benefit. History tells us that such an approach will always raise demand.

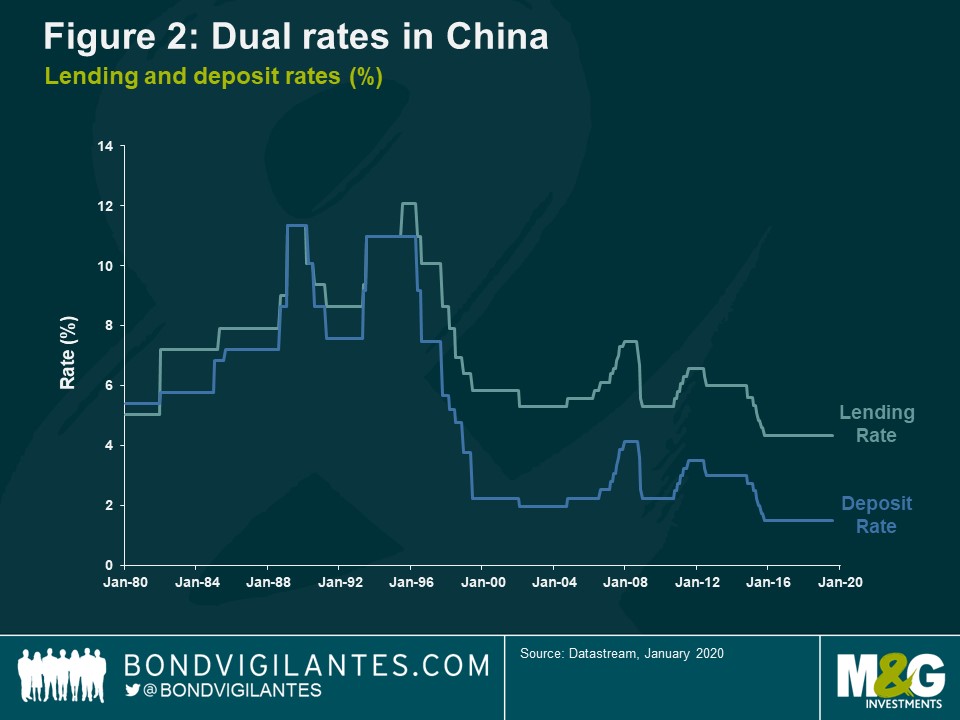

The strongest recent evidence is from the Chinese banking system in the 1980s and early 1990s (see the differential movements in figure 2, prior to more parallel shifts in recent years).

Interest rates on deposits and loans were set independently. When stimulus was required, interest rates on loans could be reduced by more than interest on deposits. In an economy with fiat money, nominal spending can always be stimulated.

Can such a policy work with a private banking system and an independent central bank? Many commentators seem unaware that in his final act as president, Mario Draghi showed precisely how it is done.

For some time now the ECB has had a method of independently affecting lending rates. Its targeted longer-term refinancing operation — or TLTRO — allows the central bank to lend to commercial banks at negative interest rates, on condition that they extend new loans to the private sector. TLTROs also exclude lending to unproductive parts of the economy, such as mortgages.

Mr Draghi’s final innovation was to introduce “tiered reserves”. This allows the central bank to set the rate of interest on the deposits that banks hold with the central bank independently of the policy rate which determines money market rates.

In one subtle gesture, the ECB in effect reduced the interest rate at which banks can fund lending to the economy and raised the average interest rate that banks receive on their deposits. This is a policy of dual interest rates.

Dual interest rates in the future

Let us consider how this policy could be extended. If Ms Lagarde needs to provide further stimulus to the eurozone due to inflation persistently undershooting the ECB’s close to 2 per cent target, she could increase the term of TLTROs to five or 10 years, at a steeply negative interest rate, say minus 1 per cent. At the same time, the bank could increase the interest rate on deposits through tiering.

Progress could also be made on how to target this TLTRO funding. Currently, the only requirement for banks to access the programme is that they use it to extend new loans, excluding mortgages. Ms Lagarde has expressed a desire to make ECB policy consistent with the eurozone policy on climate change.

TLTROs at negative interest rates should be available only to banks that are directly using the funds to finance sustainable energy investments. In one relatively simple policy move, the supposed impotence of monetary policy becomes an enhanced Green Deal.

It came as little surprise that the take-up of the recent programme was muted. For example, the current three-year TLTROs at minus 0.5 per cent are only a marginal improvement on available market-based funding. But a 10-year loan at minus 1 per cent or minus 2 per cent would be game-changing.

Dual interest rates and sustainable TLTROs should be at the heart of Ms Lagarde’s review. Monetary policy is very far from running its course. There is scope for a major shift in its power. Therein lies the challenge for the bank’s new president. She has promised openness and transparency. Being explicit about the effects, and powers, of this policy would be a great manner in which to begin.

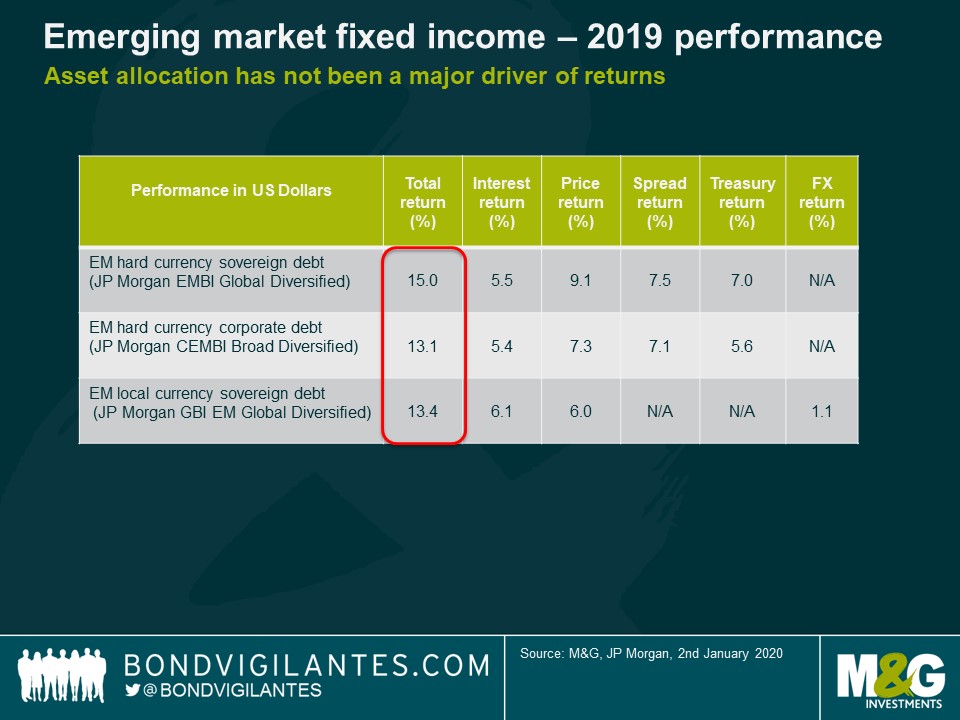

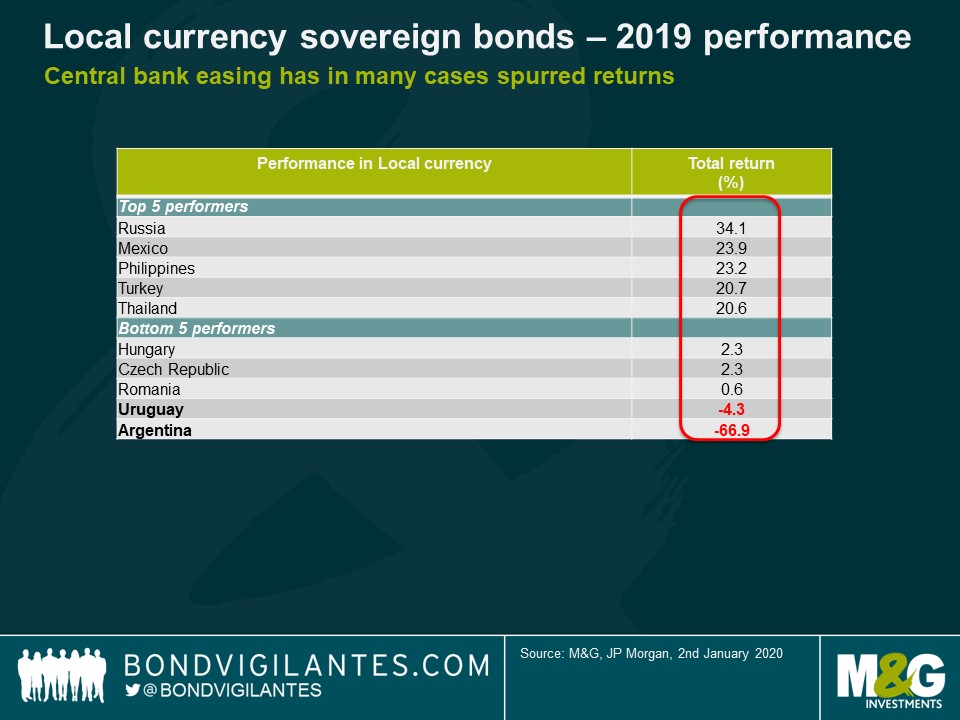

2019 proved to be a spectacular year for returns in most asset classes and emerging market debt was no exception. Returns were driven by a combination of cheaper valuations to begin with and also helped by the market-wide U-turn in going from pricing in Fed hikes to cuts and by the subsequent US rate rally. Some key risks were also priced out as the year moved on, including the US-China trade war after the Phase 1 deal was announced.

Asset allocation between hard, local and corporate debt was not a major call in 2019

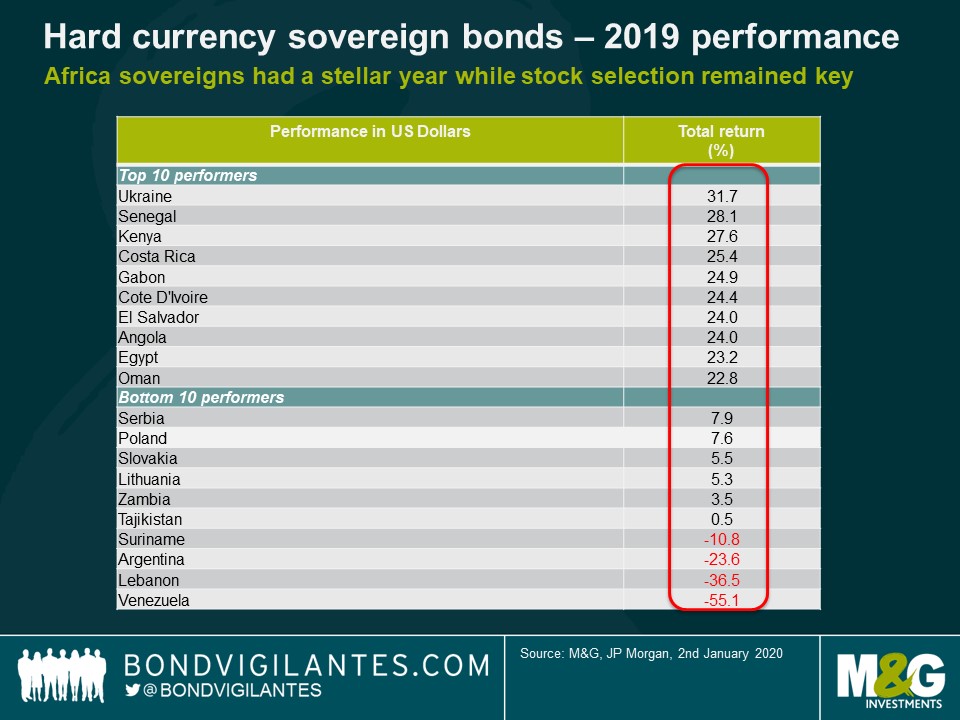

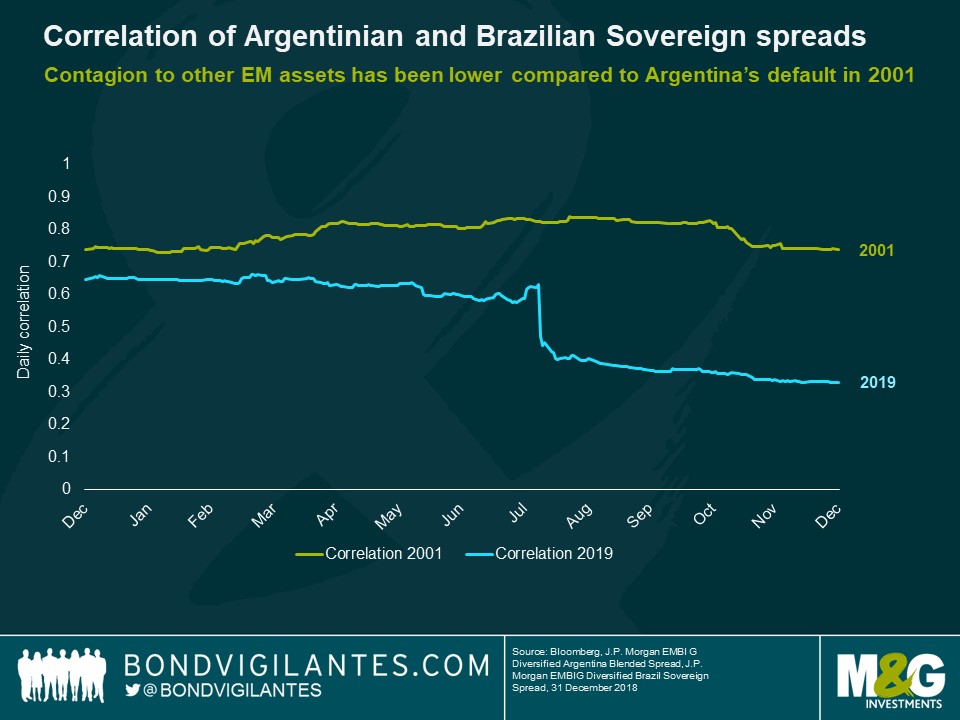

The key call in 2019 was to be long most assets and avoid the large tails, particularly Argentina and Lebanon which had a combined index weight of over 5%. This makes 2019 one of the years with the largest percentage of assets heading into a restructuring since 2001, when Argentina entered its last restructuring.

Differentiation of performance between countries and also within countries

Despite the high level of debt becoming distressed in 2019, it is encouraging that markets (correctly) treated both sell-offs as being idiosyncratic, not systemic. The correlation between Argentina and Brazil spreads, for example, was much lower this time around than in the early 2000s. The asset class is much more diversified than it was in the early 2000s: there are almost 80 countries represented now, while there were fewer than 20 then. Many countries, Brazil included, also managed to improve their debt profiles by funding more in their local currency instead of via external debt. This increased resilience and has helped to lower contagion risk.

It was also reassuring to note that, even within single countries, there were large differences between individual credits. For example, while Argentinean corporates underperformed somewhat, they still returned a not-too-shabby 8.4% in 2019 despite the unfavourable macro environment. Investors have been able to differentiate credits, including the ones that have lower leverage and foreign exchange earnings.

Similar divergences in outcome were also seen in local currency bonds where, for example, contagion from the depreciation of the Argentinean Peso only mildly impacted Uruguay, an economy which has strong trade and economic links with its neighbour.

Outlook for 2020

The stellar returns produced in 2019 are unlikely to be replicated in 2020. This is mainly since starting valuations, particularly in spreads but also in local rates, are less favourable than those which we had a year ago.

Below are three scenarios of potential returns. Of course, there are several assumptions that need to be made here. The below scenarios assume parallel spread or yield shifts and include the initial carry but not the difference in yield movements through the year.

Scenario A: Unchanged

The unchanged scenario (which almost never happens in EM) outlines potential returns should everything be constant: essentially returns based only on carry and with no currency movements versus the US dollar.

Scenario B: Bullish

A bullish scenario would reflect a supportive macro environment with growth improving in many EM economies, the US slowing only mildly, continued easy monetary conditions by developed market central banks and no worsening of global geopolitical risks – of which there are plenty. Read Charles’ recent blog for a sample of some potential geopolitical risks for EMD investors to watch in 2020.

Scenario C: Bearish

A bearish scenario would reflect a more challenging macro environment, with global and EM growth slowing further, or a scenario of less accommodative policy by global central banks and rising inflation, a worsening of geopolitical risks or policy mistakes in various economies.

Given that few EM central banks are likely to continue cutting rates this year, currencies rather than rates will likely be the key driver of returns in all scenarios. Most EM and DM central banks are also now done with or close to ending the monetary easing cycle, so there is much less scope for a rally on local rates.

Despite favourable valuations of EM currencies (in absolute terms but also relative to external debt), I remain neutral overall in terms of asset allocation given the uncertainty of the various geopolitical risks and potential impact on the US dollar. Similarly to my view in 2019, I do not expect asset allocation to be a major driver of outperformance but rather a directional call on the markets and, to a lesser extent, specific countries and managing tail-risks appropriately.

Key country calls will be centred around the higher yielders such as Argentina, in which we moved last month from neutral to small overweight after the sell-off, expecting a higher recovery value than current prices (low to mid 40s) and a restructuring being completed in 2020. Other likely candidates include Ecuador and select frontier countries such as Sri Lanka, Ghana or Ivory Coast.

As a consolation, while EM debt may not look cheap when compared to prevailing valuations a year ago, most other asset classes (equities, US high yield) have also rallied materially. So on a relative basis, maintaining exposure to the asset class may still look like an attractive proposition for its income in an environment of still low yielding assets elsewhere.

Last year was very eventful in emerging markets with its share of US tariffs/sanctions, regime changes in many countries, mass protests across the board and Carlos Ghosn escaping Japan to soon-to-default Lebanon on the very last day of the year! 2020 promises many geopolitical risks. We have compiled some of the key risks below for developing economies, including “the biggest crisis no one is talking about”. Brexit has been intentionally omitted.

Persian Gulf tensions: One knows geopolitical risk matters when a few unsophisticated drones can suspend 5% of global oil supply (or 50% of Saudi Arabia’s oil capacity) over one night. It happened in September 2019 and it reminded everyone not only how fragile the Persian Gulf status quo was but also the far-reaching impact any type of escalation could have for the rest of the world with crude oil up +15% the day following the drone attack. Whilst the strait of Hormuz crisis seems to have abated in the second half of 2019, Iran now faces parliamentary election in February 2020 in a context of a sharp economic recession (IMF predicts -9.5% GDP growth in 2020) after two years of unilateral sanctions from the US (since May 2018). Elections could well revive tensions this year and escalation in the Middle-East could have a significant impact on asset prices in the region as the risk premium remains relatively low in some stronger-rated countries such as Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Kuwait or the UAE. Some weaker countries like Bahrain or deteriorating credit stories like Oman are even more vulnerable. Finally, another source of concern is Iraq where public discontent is growing quickly on the back of government corruption allegation. Elections in 2020 are a possible scenario and Saudi Arabia’s influence in the country has increased in order to counter-balance Iran’s alleged control of some Iraqi Shia militias. The pro-Iranian demonstration at the American Embassy in Baghdad a couple of days ago, followed by the US killing of a top Iranian General in Iraq on 2nd Jan, are here to remind us that the US-Iran tensions are unlikely to vanish in 2020.

US-China trade war: This is one of the biggest risks for emerging markets whose economies continue to rely extensively on global trade. The main channel of contagion comes from weaker Chinese GDP in turn resulting in lower demand for commodities. For instance, Sub-Sahara Africa is China’s second-largest supplier of crude oil after the Middle-East and also provides metals. Since 2014, most countries in the region have seen a significant decline in trade with China after two decades of growth. The US-China trade war has obviously exacerbated the global trade problem and some Asian economies are now seeing falling supply-chain related exports due to the decline in China exports to the US. However, some developing countries have emerged as winners. Vietnam, Mexico, Malaysia and Thailand all have benefited from either a direct rise in exports due to diverted US demand from China and/or an indirect rise in exports related to the supply chain of China’s competitors. There is also hope for a sustainable deal between China and the US which would revive global growth in 2020 and beyond. In December, both parties agreed on the “phase one” deal with some reduced US tariffs in exchange of improved protection for US intellectual property and additional purchase of US products from China. Rather truce than a deal though. The trade war is likely here to stay.

Taiwan elections, Hong Kong, North Korea and South China Sea: The incumbent President Tsai (Democratic Progressive Party) is likely to be re-elected in the Taiwanese January 11th presidential elections. Her party benefited from stronger economic data in recent months thanks to the US-China trade war which redirected some manufacturing to the island. The Hong Kong protests have also helped the independence-leaning party to gain ground over rival and more China-friendly opposition party. In Hong Kong, the protests that started in June 2019 are due to continue in January as the pro-democracy protesters now have more political capital since the landslide victory at the Nov-19 local elections. The domestic issues, coupled with the US-China trade war, have had a sharp impact on economic activity and job losses. The Chinese authorities have so far been relatively quiet but that might change after the Taiwanese elections. Elsewhere in Asia, year-end 2019 had its share of geopolitical escalation. North Korea said that it was considering new missile testing, against the commitments taken to denuclearised the Korean Peninsula. Malaysia recently joined Vietnam and the Philippines in their tough stance against China’s claim that the whole South China Sea belongs to China. The South China Sea has long been contested by many parties due to its geostrategic importance (military, shipping lines, natural resources).

US election: Another key geopolitical risk as Trump has been the most unpredictable US President in recent decades and in particular when it comes to foreign policy. The new US sanctions and tariffs the world has experienced since he took office are numerous (EU steel & aluminium tariffs, NAFTA renegotiation, China tariffs, Russia – although initiated by Obama, Iran U-turn, withdrawal of the Paris Agreement, etc.). Under a different US personality, emerging economies might not face the same unpredictability of one of the largest trade partners in the world and perhaps not constantly worry about the US dollar being used as a foreign-policy weapon. However, countries like Russia, Turkey or Saudi Arabia have benefited a lot from Trump’s relatively benign stance towards them and a change in the US administration may become bad news. On the economic front, most investors expect equity markets to reprice in the case of a Democratic victory. This would result in the Fed easing and a weakening of the USD. Whilst supportive of EM FX in theory, a weaker US dollar may also reflect a weaker US economy which would both impact US demand for commodities and affect risk assets across the world. In this scenario, EM debt as a whole may not perform well. Expect more clarity in March/April when the Democrat candidate could be known.

Turkey – US sanction risk: Turkey’s purchase of the Russian S-400 missile defence system – together with the October military operation in Northern Syria – have increased significantly the risk of sanctions from the US Congress. These could come in the form of visa bans for officials and asset freezes for state-owned bank Halkbank (Iran-related sanctions). The US have also threatened to close down two military bases in South-eastern Turkey. It remains unclear whether the US are willing to also implement broader financial sanctions on the banking sector as a whole, similar to what they did with Russia after the annexation of Crimea. Given Turkey’s banking sector’s huge need for short-term external funding, the latter option would bring material disruption to the Turkish economy and as a result is less likely because an implosion of Turkey would not be good news for either the European Union (Syrian refugees agreement with Erdogan) or the US (Russia would likely increase its influence in the region). Policy mistakes are another key risk, such as an aggressive monetary and fiscal easing to achieve the government’s unrealistic 5% growth target for next year. Bond spreads in Turkey, whether sovereign or corporates, have rallied hard late 2019 and barely reflect either policy-making or US sanction risks. Asset prices leave little room for error in 2020.

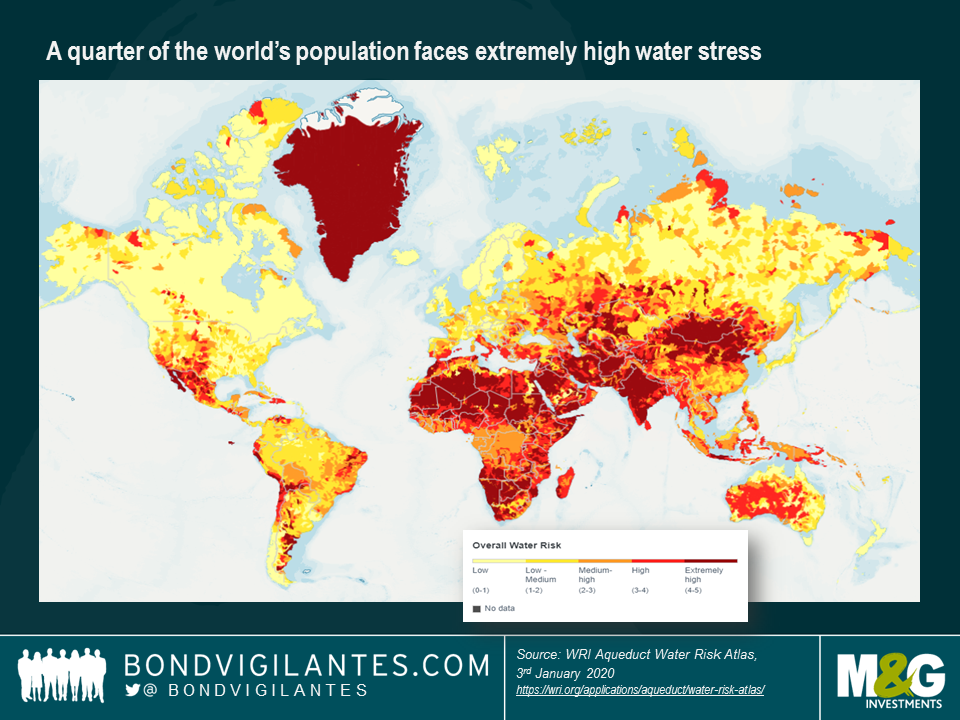

Water Stress – “The biggest crisis no one is talking about”: In August, this is how the World Resources Institute (WRI) – which focuses on climate, food, forests and other environmental and social issues since 1982 – described global water stress risk. The June-2019 Chennai water crisis was just an example of this, when tap water had stopped running in India’s fourth-largest city (8 million people) after two years of bad monsoon rainfall and also because rivers are polluted with sewage. Unlike the emotionally-driven climate activism from Greta Thunberg, global research organisation WRI published in August 2019 a research-backed Aqueduct Water Risk Atlas (cf. picture) which found that 17 countries accounting for a quarter of the world’s population were facing extremely high water stress with consequences “in the form of food insecurity, conflict and migration, and financial instability”. Developing economies are increasingly aware of water management because water scarcity / stress may act as a real impediment to social and economic growth if not properly managed by countries. There are other ESG factors that matter for growth but investors tend to focus on the geopolitics of oil, climate risk in general or deforestation. Too few investors are really looking at water stress as a structural risk of economic, political and social issues. The 2017-18 Cape Town or the 2019 Chennai water crisis are examples of water stress that constrained economic growth and brought social discontent. But water stress can also contribute to escalation of armed conflicts like in Yemen or Syria where the water crisis has been a critical factor.

India/Pakistan: India PM Modi’s new Indian Citizenship Law passed in December 2019 has incorporated religious criteria for refugees or communities seeking naturalisation. The law provides facilitated eligibility to become Indian citizenship to Hindu, Jain, Parsi, Sikh, Buddhist, and Christian minorities – but not Muslims – from Afghanistan, Pakistan and Bangladesh. Widely criticised, the new law has been the subject of mass protests across the country and in particular in majority-Muslim state territory Kashmir. Early 2019, the region again saw an Indo-Pakistan military standoff after a vehicle-borne suicide bomber killed over 40 Indian forces in February. On the economic front, Pakistan (credit rating B3/B-) is also under pressure after GDP fell sharply in 2019. The IMF programme requires aggressive fiscal and monetary targets which already have resulted in anti-government protests. Any escalation of geopolitical risk with India would not be welcome.

Russia/Ukraine: Will last year’s good news carry on in 2020? The conflict between Ukraine and Russia which started in 2014 after Russia annexed Ukraine’s Crimea peninsula – death toll of 13,000 to date – has considerably improved since the Paris Summit on 9th December. Presidents Putin and Zelenskiy agreed to fully implement an existing ceasefire and on 29th December a long-awaited prisoner exchange of 200 prisoners happened. Mid-December, after many months of negotiations Ukraine (through Naftogaz) finally signed a new gas transit contract with Russia (Gazprom). This should indirectly help Ukraine’s budget as Naftogaz is a state-owned entity. The IMF programme and reform agenda of new President Zelenskiy are other positive factors. But asset prices have largely priced in the positive trend with Caa1/B- rated Ukrainian sovereign bonds in USD trading as tight as just over 200 basis points for a 2021 maturity… and mid 400 bps for the 5-10yr part of the curve. Clearly the market is Putin a blind eye on any downside risk from geopolitics in Ukraine, rightly or wrongly.

Social unrest across the globe: It’s not a surprise to anyone when the French demonstrate with yellow vests or go on strike against the pension reform. However, the violent mass protests in Chile following a raise in Santiago’s subway fare took most investors by surprise in 2019. And last year saw an almost unprecedented series of protests against corruption, inequalities and long-standing regimes. In no particular order: Lebanon (PM resigned amid street protests), Sudan (President Omar al-Bashir was ousted after a coup d’état following mass protests), Algeria (President Bouteflika departed – he was in power for 20 years), Iraq (PM resigned), Bolivia (Morales resigned after protests), Puerto Rico (Governor stepped down), Iran (mass protests), Colombia (mass protests), Argentina (political change), Hong Kong, etc. The trend had started since the Global Financial Crisis but clearly accelerated in 2019 and whilst each protest has its own dynamics, to a certain degree they all shared the same claim for fundamental changes in the system they lived in. Have financial markets priced in the structural rise of populism that comes from public discontent? Surely there is more to come in 2020 and investors are not immune to new surprises like the Chilean protests.