A lot can change in a month. While many of us grapple with the new daily regime of lockdowns, remote working, home schooling and scouring the shops for that last fabled toilet roll, it’s worth taking a moment to review what has happened to credit markets over the past few weeks.

Even in social isolation, one would be hard pressed to miss news headlines reporting the sell off in equities and corporate bonds following the evolving threat of a global pandemic and what this could mean for growth, consumption and corporate solvency. It’s now broadly accepted that most developed countries will enter recession—but for how long and how deeply?

Falling bond prices have led to a rapid widening in credit spreads led by USD bonds. USD investment grade bond spreads are now trading at 11 year wides, last seen during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). In fact, USD investment grade bond spreads are trading wider today than USD high yield spreads were back in February. EUR investment grade bond spreads have fared somewhat better, trading at levels last seen 8 years ago during the European Debt Crisis.

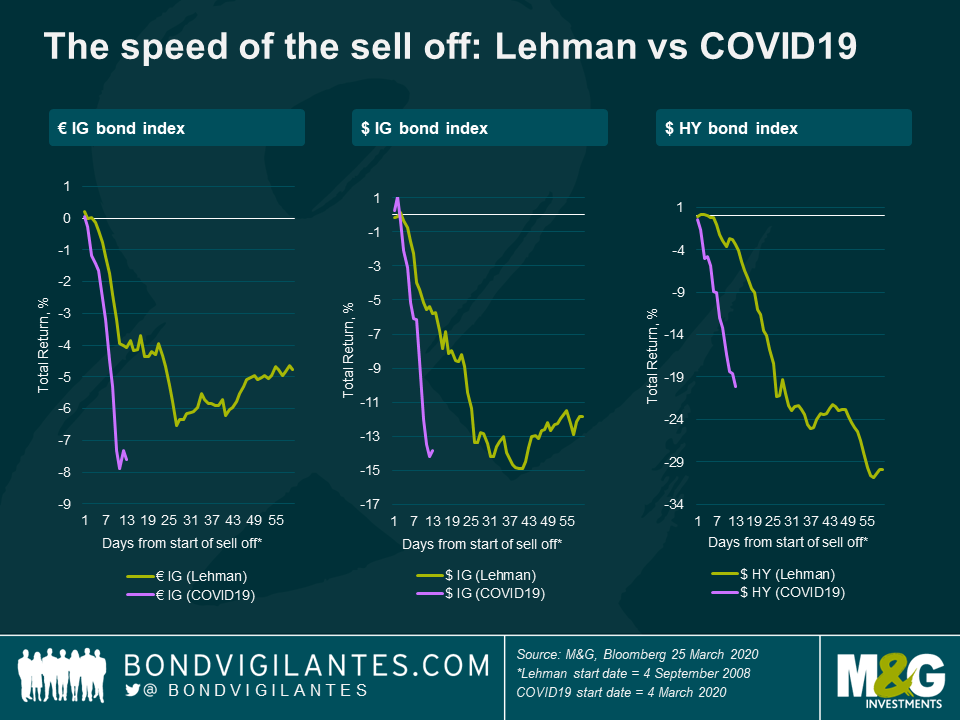

Perhaps what has been most noticeable this time is the speed and magnitude of the price moves, which make this one of the most violent corrections on record.

During the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008, it took USD IG bonds 37 days to fall by -14.5%. This time the same decline took only 12 days. Similarly, during the Lehman collapse, EUR IG bonds took 27 days to fall -6.5% while this time it took fewer than 11.

The aggressive pace of repricing is also evident across many other facets of credit.

Credit quality

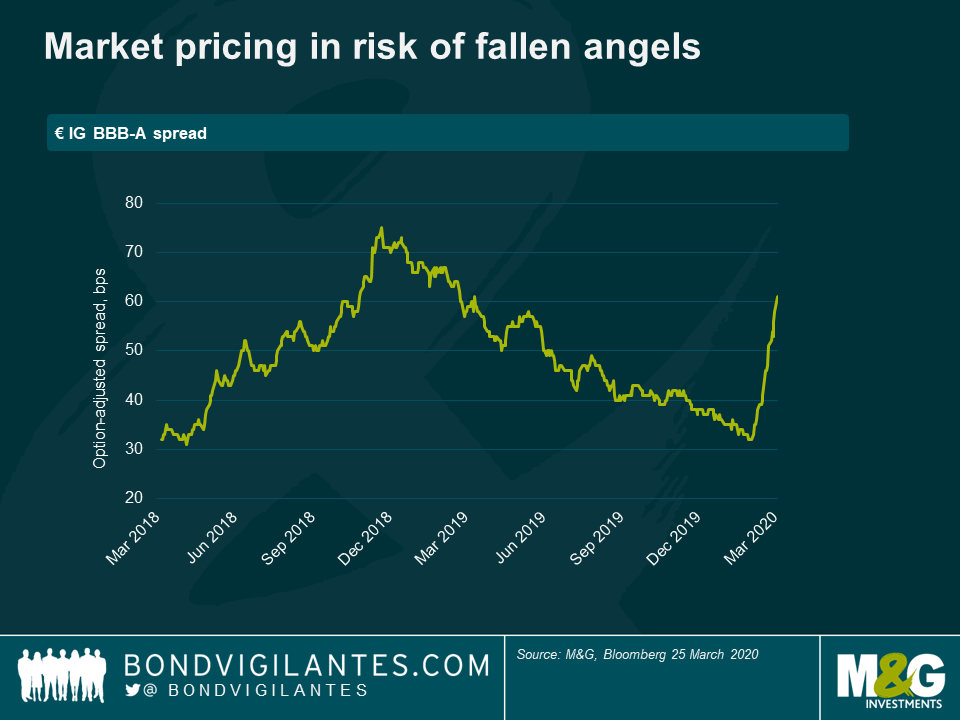

Lower quality BBB credits have steadily underperformed single-As, indicating a flight to quality as the recessionary risk of falling angels (companies rated at the bottom of the investment grade spectrum, BBB, falling into high yield) rises.

Credit term structure

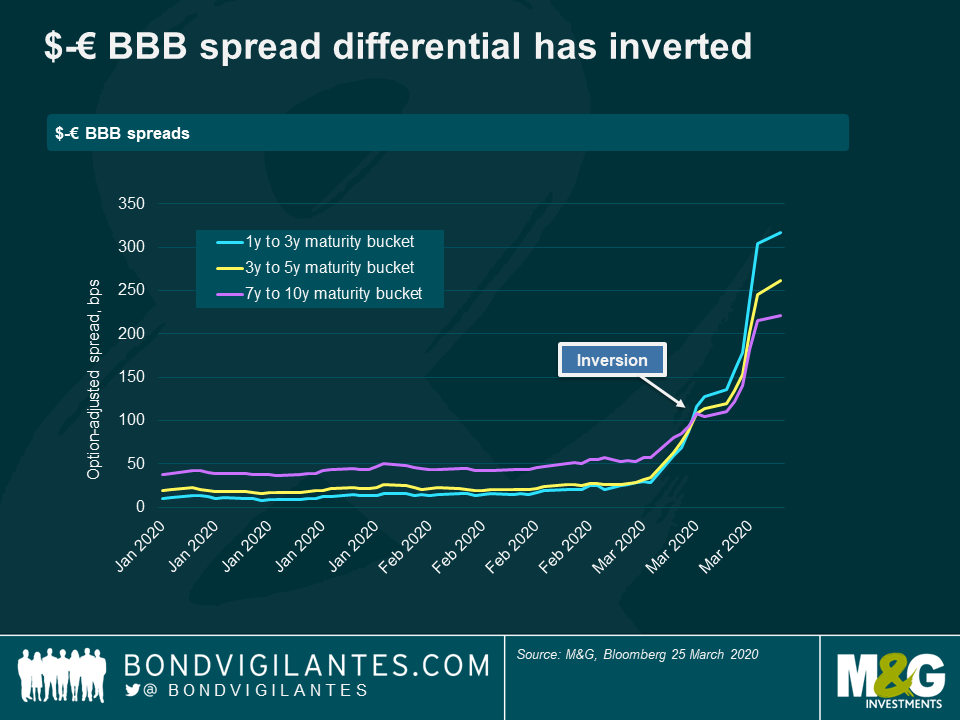

Flattening of the IG credit curve has accelerated and nears inversion. Part of this has been driven by a bias from asset managers to sell down short-dated IG credit in order to meet redemptions, in favour of crystallizing losses on longer-dated paper.

Cross-currency credit spreads

The $-€ BBB spread differential has not only widened significantly over the past month but inverted, further demonstrating liquidity stresses on the short-dated part of the credit curve.

Euro financials vs industrials

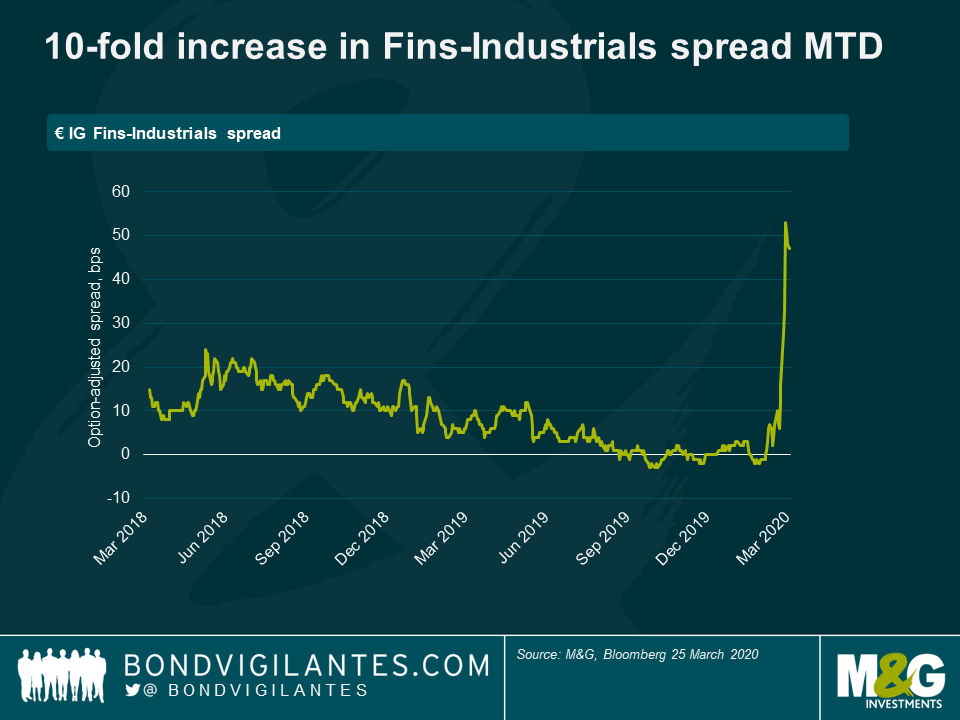

There have also been big changes in inter-sector valuations: the market now prices financials at an excess spread of more than 50 bps relative to industrials, a 10 fold increase from a few weeks ago.

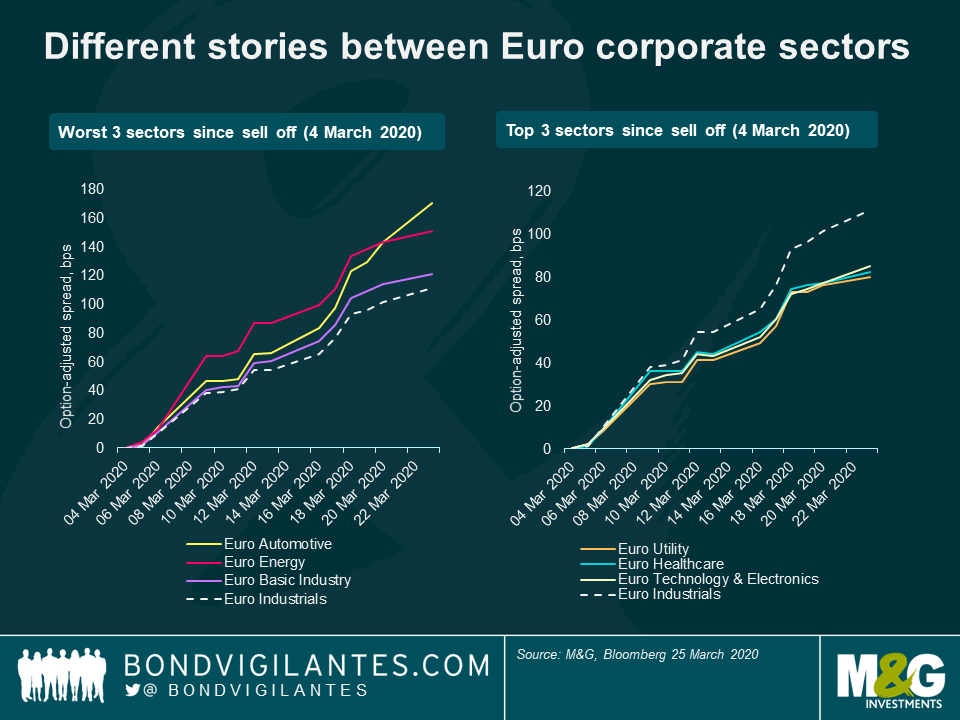

Euro Industrial subsectors

Within the Euro industrials, it’s unsurprising to see those industries most sensitive to a deteriorating growth outlook lagging the Euro corporate bond index, namely autos, energy and basic industry.

At the other end of the spectrum, those industries that have outperformed (at least on a relative value basis) are those likely to benefit from lower rates (Utilities), greater demand for health-related services (Healthcare) and those services that will enable us to adapt to new ways of living and working (Technology).

Such extreme moves are understandable given the unprecedented (at least in modern times) viral outbreak of COVID19. As my colleague Richard Woolnough points out, this time is different.

However, there are other factors at work here that have intensified the moves. The most notable is the evaporation of liquidity in some of the most liquid bond markets. There are likely several contributing factors, all inter-related.

For one, market participants have been uprooted from their normal trading floor environments. Many have been moved to disaster recovery sites, split up into multiple sub-teams or isolated at home. This naturally slows down communication and the market making process.

Secondly, with front office, ops and tech staff split up, many trade matching algorithms have been turned off, slowing down price discovery and forcing dealers in some cases to match orders manually.

Thirdly, there is an inability for dealers to expand their balance sheets and commit principal capital at times of greater demand for liquidity. The pro-cyclical nature of regulatory capital rules requires banks to hold more capital as volatility rises, in turn taking liquidity out of the system when it needs it the most.

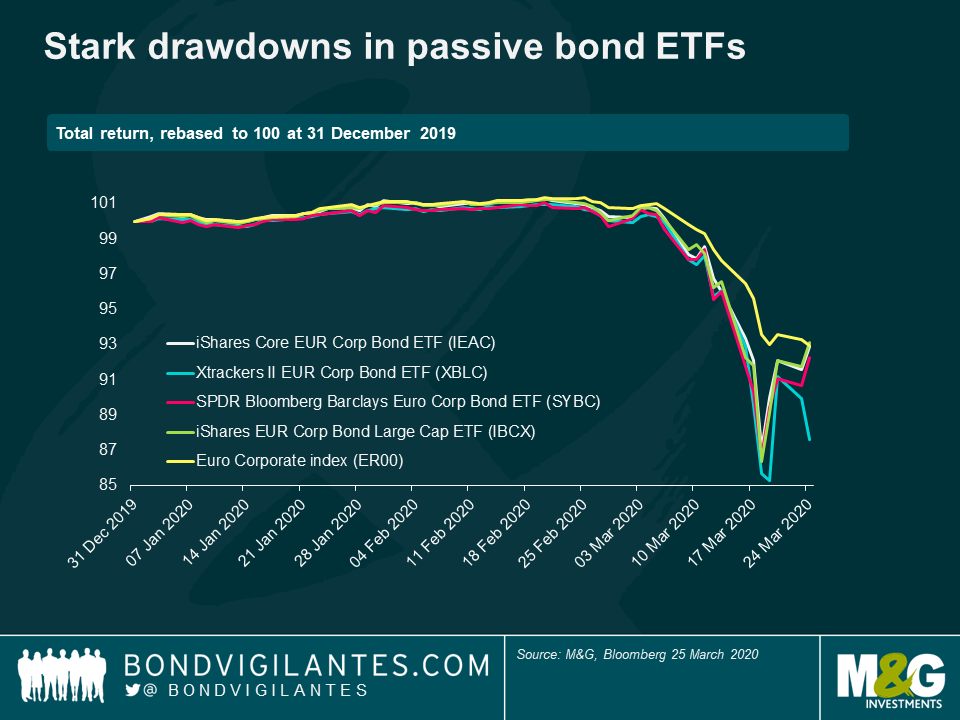

Finally, outflows have been severe. One segment of the market that has been hit particularly badly is passive bond ETFs. They have grown exponentially over the past decade, promising retail investors close to benchmark returns, low costs and instant liquidity. However, the liquidity mismatch between ETF prices and their underlying bonds has caused many ETF prices to swing significantly below their net asset value. This is a function of poor dealing liquidity (wide bid-offer spreads) as described above. This in turn creates further forced selling, putting still further pressure on bond prices and creating the so called “doom loop”. While some of the ETFs have started to recover, the drawdowns have been stark.

No doubt more will come to light over the coming weeks and months. Several governments have announced new bond buying programmes (notably the US and UK), while others have increased existing asset purchases (EU). This type of policy response aims to address directly the aforementioned liquidity challenges. Ultimately this should work, assuming that these efforts are coordinated and implemented swiftly. This, given past experience, is possibly the biggest risk of all.

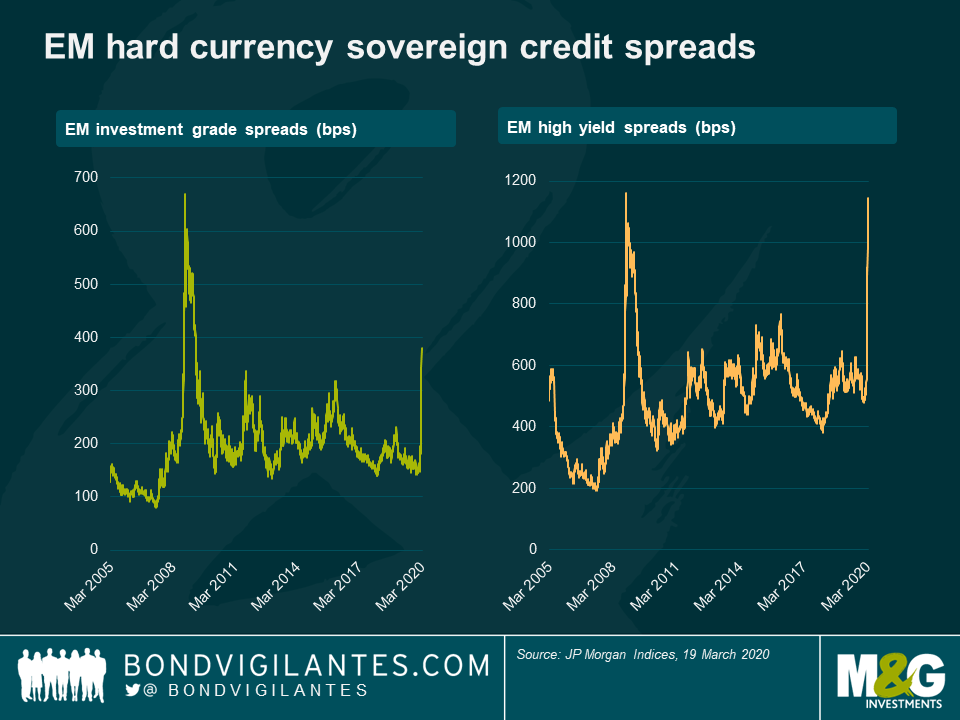

Emerging markets have recently seen other impacts than the tragic ones of COVID-19 outbreaks on their societies and economies, with spreads widening considerably. Three factors have been at play. First, was a rapid sell-off in global stock markets that followed the realisation that the global economy is heading for a recession. Second, investors shifted to intense risk aversion and the demand was for US dollar cash buffers. Cash became king, overlooking many typical safe-haven assets. Third, was the breaking up of the OPEC+ agreements, that sent global oil prices — already weak from lower demand — into a tailspin. What is bad for oil is terrible for oil producers (see our recent blog), but it also tends to be a drag on all emerging markets: while oil-importers get some trade balance relief, they also tend to face higher costs of borrowing and the effects of weaker market sentiment.

Investment grade spreads are above the peaks of any recent bout of market volatility with a speed unmatched since the global financial crisis. Emerging market higher yield bonds soared in similar fashion, through a 1,000 basis point threshold above US Treasuries.

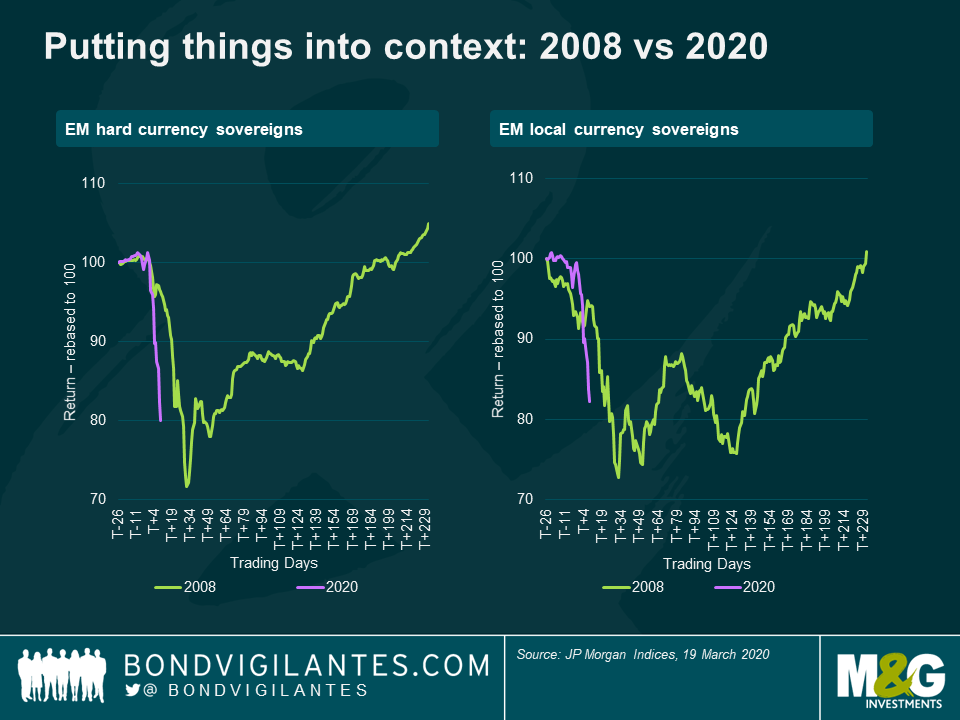

The potency of the market’s risk aversion was illustrated by record single-week outflows from emerging market bond funds. These outflows reduced the level of both hard currency and local currency investment, with both selling aggressively. To put the speed and intensity of the move into context it is worth comparing it to 2008.

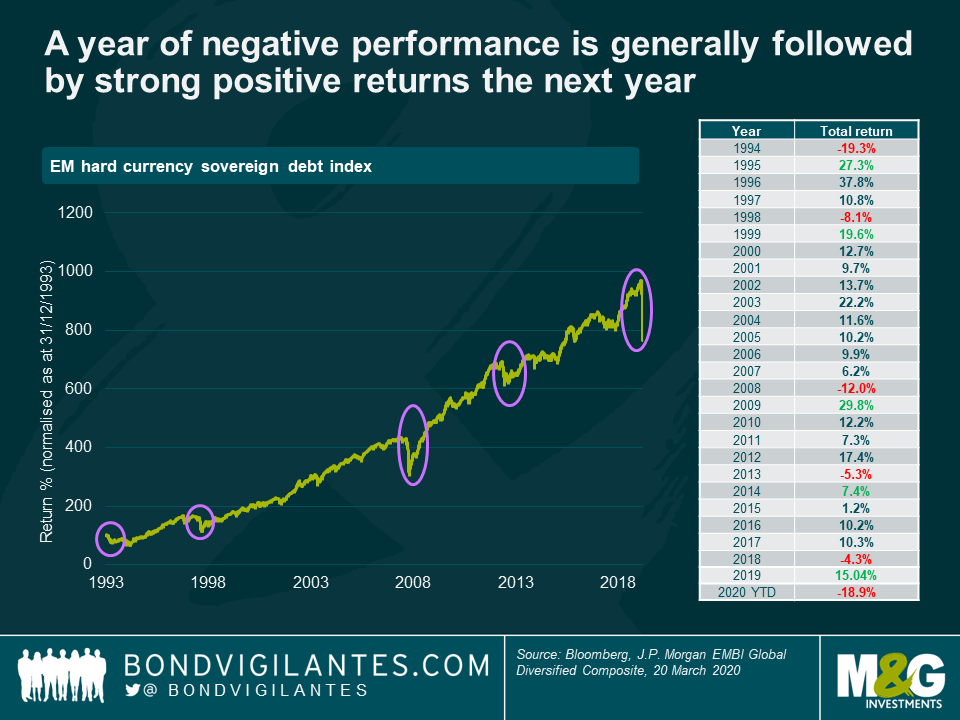

So where does it leave us? It might still be soon to know how long this will last, but historically, a year of negative performance — of the emerging market hard currency sovereign bond index — is followed by strong positive returns the next year. While history is no guide to the future, it suggests that investors might look to reposition money pulled from emerging markets once risk aversion becomes less intense.

Emerging markets are feeling the direct economic, social and health impacts of COVID-19 outbreaks, plus the demand shock from their efforts to shut down and restrict the spread of the virus. Negative impacts are also being channelled via reduced travel and tourism sector earnings, constrained trade, and lower remittances; each exacerbated where there is a reliance on exporting commodities whose prices have been softened by the global recession.

While the impacts are considerable, the global response is also bold. Emerging markets are joining advanced economy central banks and governments in announcing huge monetary and fiscal stimulus. Even where emerging markets are already running high deficits, or are reliant on foreign debt for their financing, there still should be some cavalry arriving. The official sector is stepping up its assistance in light of COVID-19, including from recent multi-billion initiatives announced by the IMF and World Bank. If sufficient, these efforts will encourage investors to shift from current risk aversion, in turn helping to ease the liquidity situation.

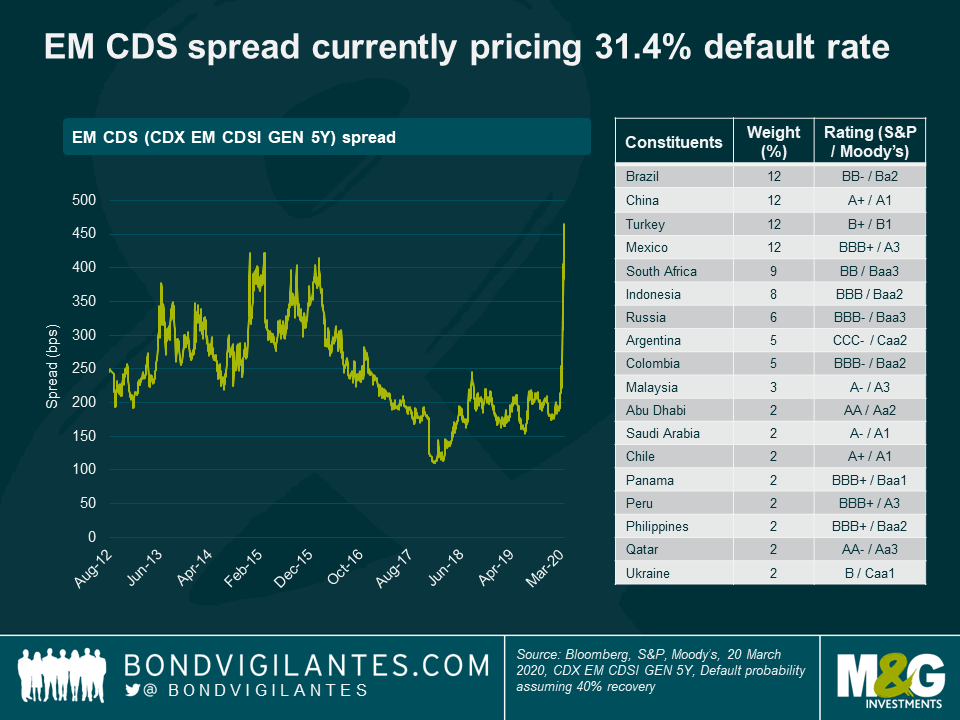

Emerging market credit default swaps are currently pricing a default rate of 31.4%. But emerging market default rates were well below that rate during the global financial crisis. This suggests that, when global financial conditions do improve, valuations in emerging market bonds and FX could suddenly look attractive. Especially in countries that have seen an impact beyond that which their fundamentals would suggest. This shortlist might include emerging markets which have already been through the peak of their COVID-19 impacts, or those who might be spared a large direct impact.

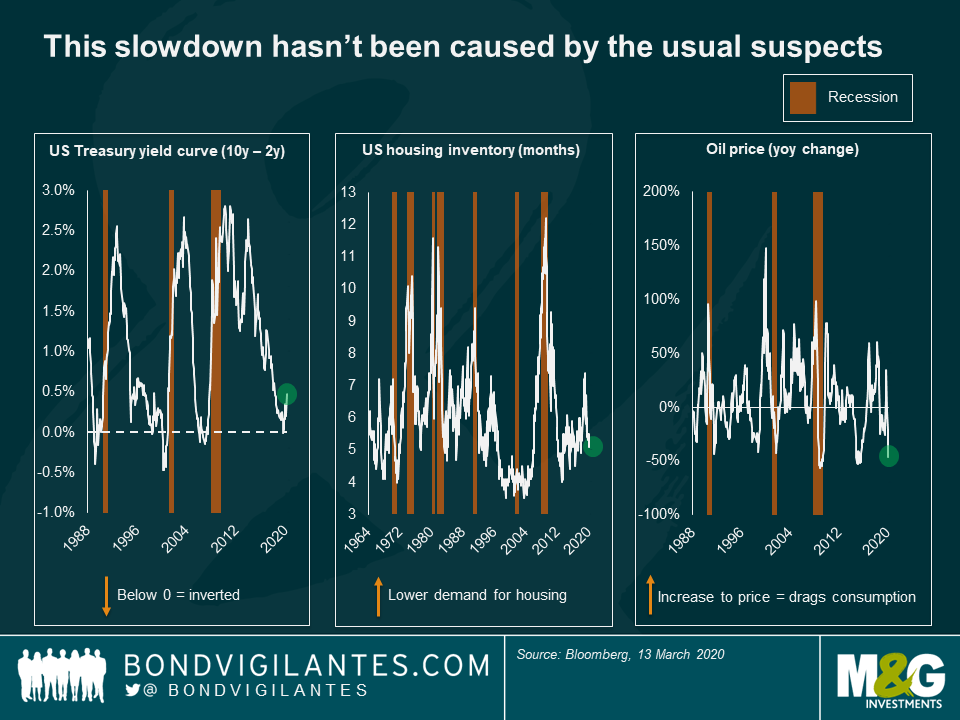

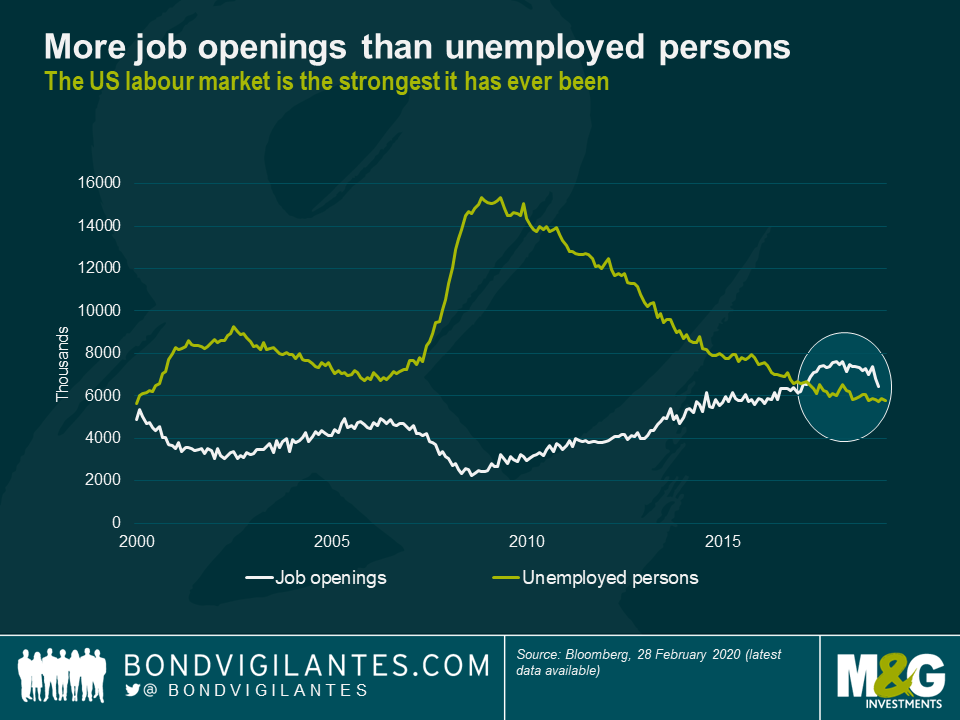

Whenever there is the threat or the reality of recession, it usually follows a typical pattern. It is engendered by tight financial conditions, a real or market bubble bursting, a dramatic rise in the price of oil, or a combination of the above. This time it is different: a stay at home recession.

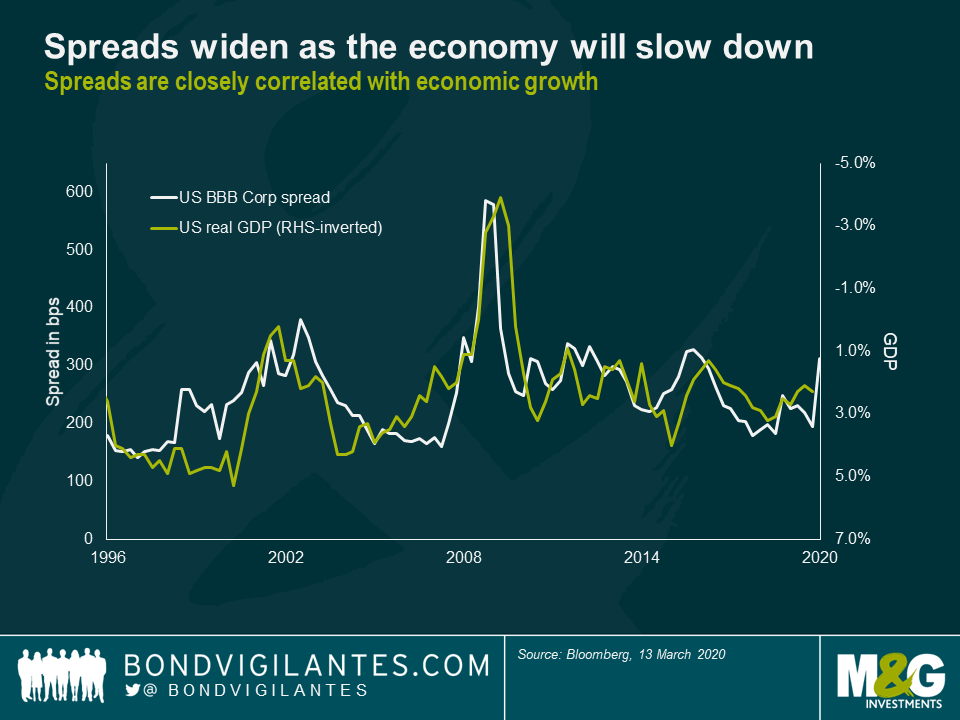

The 2020 economic slowdown isn’t due to any of the usual suspects, namely the US Treasury curve inverting, the US housing market slowing or a high oil price. Rather, it is due to the virus outbreak leading not to a policy error, but a policy-led recession. In response to the virus outbreak, governments around the world have reacted understandably by encouraging their populations to curtail day-to-day activity. For example, I am writing this on my usual journey in and the car park and train are deserted. We will all have our own anecdotes of this dramatic change to daily life. This will result in a collapse in GDP. Credit spreads are closely correlated with economic growth, and spreads have already reacted aggressively to lower GDP expectations.

Fortunately, we enter this recession with already very accommodative monetary policy from central banks. Monetary policy takes about two years before we can see its effect in the economy. For example, we saw a slowdown in 2018 a couple of years after the Fed hiked rates into 2016. Now the economy has a lead, the Fed having stopped hiking rates in early 2019 and then proceeded to cut. While the ECB has limited scope to react due to its already rock bottom policy rate, the Fed and BoE do.

There are three stages to a recession – how is this one going to be different?

Stage 1: into recession

This is the most certain recession we have ever seen: we can all observe the dramatic fall in daily activity around us. Discretionary spending has been curtailed, and the most expensive discretionary spend, travel and tourism, has been hit the most. This is not a slow evolution where individuals gradually discover the new economic reality, this is an in instruction to everyone to stop consuming. This instruction is worldwide and instantaneous, something that has never happened before.

Recessions are usually described as V or U shaped. The first leg of this recession will resemble the U shaped form. It will be vertical and dramatic, and the largest ever collapse in GDP on a weekly and monthly basis in many countries.

Stage 2: end of recession

Given that the recession’s speed and depth is due to the virus and resultant government action to prevent us mingling, we have an unusually strong idea of when and how the recession ends. This virus appears to exhibit seasonal patterns like influenza and, once it has made its way through the population, immunity can build up. At some point therefore, presumably within three months, government policy will be changed and we can potentially return to normal behaviour. This bounce back will be enormous as the population is no longer told to stay at home. Thus, economic data will show a rapid rebound: it will not be a V or a U, rather it will look like an l. It will be the biggest ever jump in GDP on a weekly and monthly basis in many countries.

Stage 3: post recession

This dramatic collapse and recovery will cause some longer term damage to the economic system. Firstly, from an overall business and personal confidence level, and secondly due to the unprecedented nature of the severe short term pain of the recession. Human behaviour may change, and vulnerable companies relying on short term discretionary spending will have been weakened and potentially permanently impaired. While some consumption will just be deferred (buying a car, for example), much will be lost (going to the cinema). On the positive side, unlike most other recessions, developed economies exhibit very low unemployment and considerable numbers of the population will remain employed and many businesses can remain stable. Hopefully there will be fiscal support for those who struggle more.

Therefore, post recession growth will return to normal but initially will be unlikely to regain its previous levels. This makes this type of recession t shaped: a sharp pull down, a sharp rebound and then back to the normal economic cycle, at probably a lower level than before unless the policy response overwhelms the downdraft, in which case we return to where we were before (T not t). For the economies most affected, this t will be a larger downdraft and bounce back, though the permanent damage may be more. For credit investors during this time, it is important as always to differentiate between credit qualities. While high yield defaults can be expected to rise (previous recessions have seen up to 30% of high yield companies defaulting over five years), investment grade companies are so-called because they should survive (with closer to 2% of companies defaulting over five years in times of stress).

This recession is different. We know why it is happening, have a far clearer idea than usual of its length and can strongly postulate how it comes to an end. Different governments and central banks are therefore working on measures to get us through the short term GDP flash crash. This has allowed the authorities to act in a bold and aggressive manner that is in itself different. This unprecedented stimulation is likely to stay in place post the shock, to ensure that the economy has a chance to get to an economic level as near as possible to its previous level.

Last week I interviewed Philip Coggan, the Economist journalist who writes the Bartleby column. His new book, “More: The 10,000 Year Rise of the World Economy” is out now, and it’s essential reading for anyone at all interested in the development of the global economy from the caveman through to the tech giants of today. One review of the book I read suggested it was a 21st century update to Adam Smith’s “The Wealth of Nations”, and defence of the liberal, open economies that we’ve come to expect today. At its heart is the idea that human connectiveness is the key to prosperity and invention – this of course raises questions about the recent rise of populism, trade protectionism, and the impact of Coronavirus, all of which might put what we’ve taken for granted at risk. The book is a great read, packed with stories and astonishing facts – for example, did you know that “knocker-uppers” (the people who would walk the streets to wake workers up to go to their jobs in the early morning) were still operating in London’s East End into the 1970s? Please take a look at the video below for the interview. You can also find our whole series of interviews with economist authors on our Bond Vigilantes YouTube channel.

And if you’d like to win a copy of Philip’s book, answer this question: What prop did Philip bring with him for our filming? Enter HERE. T&C HERE. Closing date for entries is 5pm UK time on Friday 27th of March.

[This competition has ended]

By Claudia Calich, Gregory Smith and Eldar Vakhitov

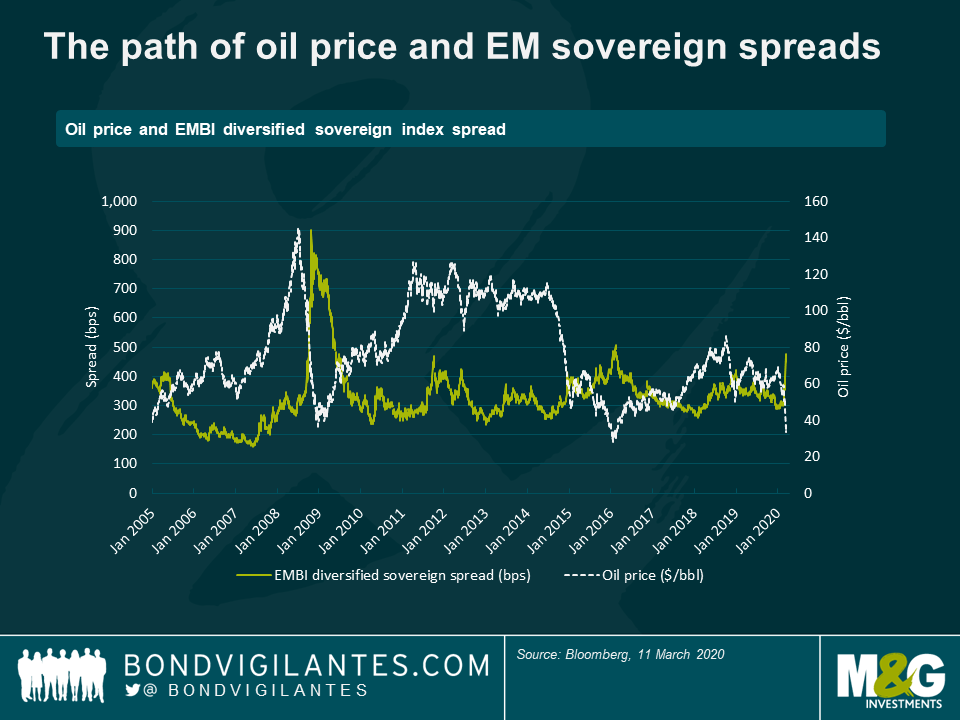

Market expectations of global oil prices have shifted several times already in 2020. The year started with short-lived scenarios of potentially higher prices, as tensions between the USA and Iran dominated the headlines. However, as COVID-19 tragically spread, the virus put a clear dent into expectations about global growth. Curfews and efforts needed to contain the virus’ spread hit both demand and supply. First in China, then globally as the virus spread. Expectations about oil prices softened accordingly, with Brent dropping from $60/bbl in late January to close to $50/bbl in early March. At this point, emerging markets were feeling the pressure of slower growth prospects and weaker sentiment as global stock markets sold-off. But there was a much bigger oil move to come.

Saudi Arabia had over the past two years agreed with Russia, and several other non-OPEC producers, to limit production in order to keep oil prices in a range broadly between $50/bbl and $70/bbl. At an OPEC plus meeting on 06 March, Saudi had hoped to secure agreement from Russia, and other oil producers, to make new commitments to hold back on supply. Saudi Arabia had not wanted to do all the heavy-lifting alone. But Russia decided not to support the cuts, and overnight the landscape shifted 180 degrees. Saudi Arabia gave up on the cuts and pledged lower prices and a greater supply of oil. This sent oil prices tumbling down to the mid-30s when markets opened on 09 March.

Brand new scenarios for oil prices were sketched out for 2020 and 2021 by the markets. They had to gauge not only the potential impacts of COVID-19, but also now an oil price war. One scenario involves Saudi’s move provoking Russia to change its stance and agree on cuts, lifting oil prices in the process. But this was not the prevailing view. Instead the idea that oil prices might remain in the 30s over 2020 dominated market thinking.

Emerging markets tend to feel strain when global oil prices drop. There is a clear impact on the oil producers. Meanwhile, oil-importers might see some balance of payments pressures easing. However, they also tend to face higher costs of borrowing and the effects of weaker market sentiment. Furthermore, oil importers are more likely to be tourist destinations than oil producers. Hence they are braced for lower FX earnings as COVID-19 travel restrictions limit visitor numbers.

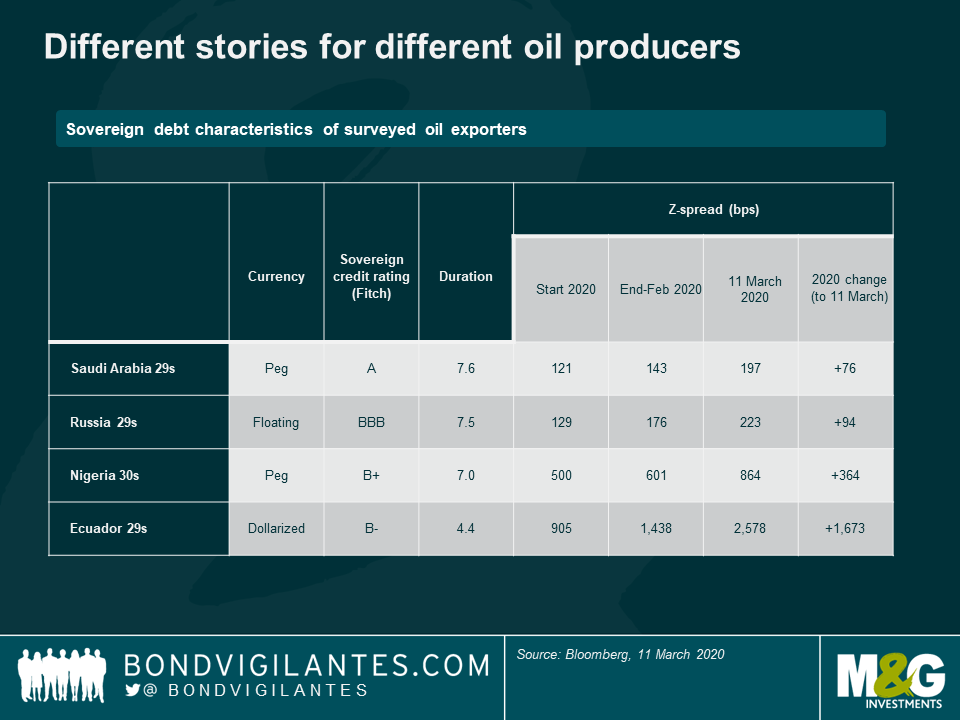

For the oil producers a move of this magnitude requires adjustment, with oil prices as much as $20/bbl below the level on which 2020 budgets were calibrated. Countries with large balance sheets, flush with saved financial assets, look stronger than those without such assets. For others with a weaker balance sheet, it is a matter of how long FX reserves will last at different extents of fiscal and external adjustment. Countries with pegged currencies are likely to need more FX reserves, than those who can adjust their exchange rates. We examine four emerging markets and discuss the impacts of potentially lower oil prices.

Ecuador

Ecuador is one of the most vulnerable countries to a decline in oil prices. As a dollarized economy, it does not have the flexibility of the exchange rate as an adjustment valve. Furthermore, although its debt levels are lower that some other oil exporters (Angola for example), it already had a large fiscal deficit even before oil prices collapsed. While the Moreno administration has had good intentions, complex domestic political dynamics ahead of a 2021 election, with the risk of populist policies returning, have made large fiscal adjustments difficult. The IMF has been very supportive thus far, but the new reality of oil prices mean that the programme assumptions will need to be re-calibrated, and future disbursements may not happen under the original schedule or at all. Should oil prices remain in the 30s for an extended period of time, Ecuador will run into a liquidity crisis. In this uncertain environment, any other potential sources of liquidity (upcoming asset sales, additional funding from China, etc) may not materialize. Ecuador has been one of the worst performers over the last week and the bonds are now pricing a very likely re-structuring in the next 12 months. Should that happen, it would be the country’s third in the last 20 years.

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia’s economy is dominated by oil production. As its riyal has been pegged to the US dollar for decades at the same rate, the government is unlikely to adjust it. But the Saudi Arabia Monetary Authority has amassed a huge amount of reserves, worth close to $500 billion in 2019 (62 percent of GDP). Oil averaging $40/bbl in 2020 could double Saudi Arabia’s fiscal deficit if budget plans are not cut and put the external account under pressure as the current account breakeven oil price is around $50/bbl. Saudi Arabia is a low cost oil producer and its accumulated buffer will help it to weather the storm and maintain its peg. But in the absence of exchange rate adjustment, FX reserves could halve if oil prices remained low until the end of 2021.

Nigeria

Nigeria, along with Angola, faces the largest potential adjustment in the African eurobond space. The Central bank of Nigeria (CBN) has kept the Naira pegged to the US dollar since the last devaluations in 2016 and 2017. The exchange-rate stability has been welcome in 2018 and 2019, enticing foreign investor demand for Nigerian short-term domestic debt. But the big drop in oil prices might put too much pressure on FX reserves—that had already been falling steadily since June 2019—if the CBN tried to maintain the currency status quo. The option of devaluation, in response to lower oil prices, is available to the authorities in 2020 as a means of adjustment. Meanwhile the government has stated its intention to re-work the 2020 budget which was based on $57/bbl.

Russia

Russia’s progress towards economic diversification has been limited in recent years, but an impressive fiscal adjustment has been implemented. The breakeven oil price for the budget fell dramatically to about $45/bbl in 2019 (from $110/bbl in 2013). A budgetary rule has kept discipline, ensuring oil revenues above $42/bbl have accumulated in the National Welfare Fund. This oil fund has reached $170bn (10% of GDP). Government debt is also very low at close to 15% of GDP. Furthermore, in contrast to most oil exporters, Russia has opted for a flexible exchange regime which provides an important avenue of adjustment to lower oil prices. Moves in the Ruble, plus FX reserves worth 18 months’ of import cover, underpin Russia’s resilience which already passed tests when it brushed-off increased US sanctions in 2018.

If Saudi Arabia’s plan is to pressure Russia into a new agreement for oil production cuts, a glance at Russia’s balance sheet suggests it might take a long time, and might end up hurting Saudi Arabia more. In any case, the greatest pressures of lower prices in 2020 would fall on the higher cost oil producers, many of which are in the US.

If a scenario of oil under $40/bbl plays out in 2020, the landscape for the EMBI diversified index oil producers will change massively. The inclusion of the GCC countries in 2019 has shifted the index’s weighting to oil producers from just under 30 percent in 2018 to 37 percent in 2020. If oil prices stick at current levels, 2020 budgets will need to be torn up and redrawn. The necessary adjustment will be substantial, with the countries with better balance sheets and adjustment tools much better placed to weather the storm of lower oil prices, all while grappling with the global impacts of COVID-19.

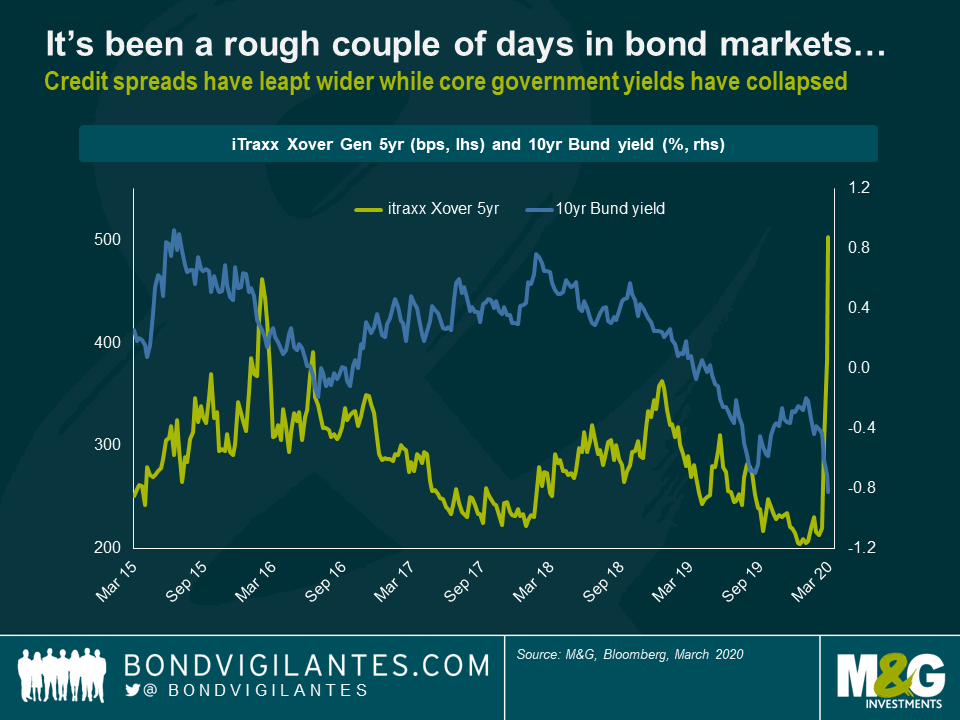

It’s been a rough two weeks in bond markets, to say the very least. Risk-off sentiment is reigning supreme. In Europe, looking at my screens this morning, iTraxx Xover—a bellwether of European high yield credit risk—jumped to its widest level since mid-2013, while the yield on 10yr German Bunds dropped to an all-time low below -0.8%.

In previous times of market turmoil, the European Central Bank (ECB) has stepped in to signal more monetary stimulus. In March 2016, after a horrendous couple of months for risk assets, the ECB announced it would ramp up its quantitative easing programme by adding corporate bonds to the shopping list. Even more dramatically, former ECB President Mario Draghi’s famous “whatever it takes” speech in July 2012 is largely recognised as one of the key factors putting an end to the European debt crisis. Considering the recent worsening of the COVID-19 situation and subsequent market reactions, all eyes are now on Christine Lagarde and her comments after the ECB’s Governing Council meeting on Thursday. In my view, essentially three options are available to the ECB this week: business as usual, measured response or big bazooka.

Option #1: Business as usual

In this scenario, the ECB simply acknowledges the heightened risks for the economic outlook and medium-term inflation in the euro area caused by COVID-19, but refrains from altering its monetary policy stance, which is already highly accommodative. The main deposit rate is kept at -0.5% and net purchase volumes under the Asset Purchase Programme (APP) continue to run at a monthly rate of €20 billion. The rationale here would be that monetary policy alone won’t be enough and that the onus is first and foremost on governments and fiscal easing. Rushing into monetary emergency measures prematurely might actually be counter-productive. The ECB switching into full-on alarmist mode could very well spook markets further. Also, considering that the ECB’s deposit rate is already deeply negative, which limits the scope of further rate cuts compared to other central banks, the ECB might conclude that it is sensible at this point to keep as much dry powder as possible to be able to act decisively later, in case the COVID-19 situation continues to worsen.

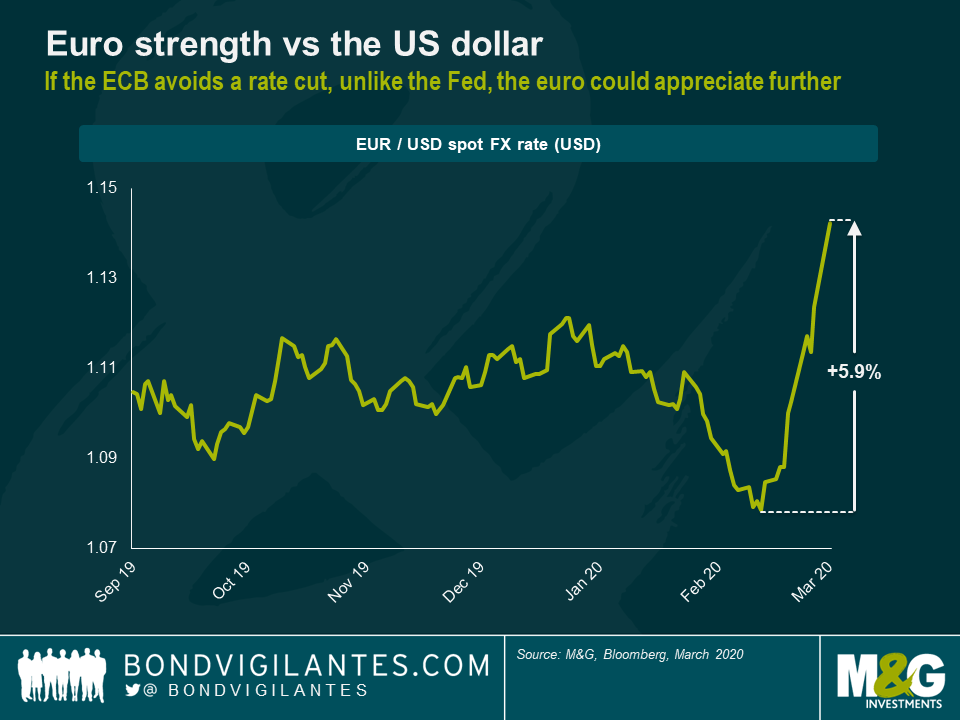

Although there may be valid reasons supporting a “business as usual” approach, I don’t think it is a likely scenario. First, expectations amongst market participants are high with regards to further monetary stimulus from the ECB. At the time of writing, the implied probability of an interest rate cut on Thursday, using overnight index swaps, is close to 100%. The ECB is under no obligation whatsoever to satisfy market expectations, of course. But avoiding the highly anticipated rate cut might fuel further turbulences in financial markets, something the ECB would rather like to prevent. Second, in a world in which other central banks—e.g. the Fed, the Bank of Australia, the Bank of Canada—have decided to cut rates in response to COVID-19, the ECB could quickly become “the odd one out” by keeping rates steady, which would put further upward pressure on the euro. The currency has already appreciated by around nearly 6% against the US dollar since mid-February. Continued strengthening of the euro would be yet another head-wind for export-driven European companies—and by extension, the eurozone economy as a whole—already suffering from weakening demand and supply chain disruption caused by COVID-19. To be clear, the ECB’s mandate does not involve actively managing the strength of the euro in the FX market. But putting an end to the recent euro rally would at least be a desirable side-effect of a rate cut, albeit not the main reason behind it, and might help in moving European inflation closer to its target through rising import prices.

In an attempt to calm markets, with the additional benefit of dampening the strength of the euro, the ECB is going to take action on Thursday, I believe. If so, the key question is of course how far will the ECB go? This leaves us with options #2 and #3.

Option #2: Measured response

In this scenario, the ECB cuts interest rates by a modest amount, say 10 basis points (bps). This would bring the main deposit rate to a new record low of -0.6%. Simultaneously, monthly net asset purchases are increased to perhaps €60 billion or even €80 billion a month. This would be a tripling or quadrupling in purchase volumes, respectively, from the current level of €20 billion, but it wouldn’t be unchartered territory. The ECB used to run its APP in the past at €60 billion (March 2015 to March 2016 and April to December 2017) and €80 billion a month (April 2016 to March 2017).

I’d say this is perhaps the most likely scenario, but arguably the least desirable one. The danger is that the ECB would get the worst of both worlds. Moderate policy action by the ECB, if not accompanied by substantial fiscal stimulus, is unlikely going to be enough to instil lasting confidence into markets that just shrugged off a 50 bps cut from the Fed. The risk-off sentiment could easily escalate further into a fully-fledged market crisis. Simultaneously, the ECB would have depleted some of its dry powder, thus limiting the scope of any additional emergency policy actions that might be necessary in the future if the adverse economic impact of the COVID-19 outbreak exceeds current projections.

Option #3: Big bazooka

The idea here be to create another “whatever it takes” moment that immediately helps calm down markets and avoid a full-blown panic amongst investors that, if left unchecked, might compromise the stability of the financial system and ultimately threaten the real economy. In this scenario, the ECB acts boldly both in terms of interest rates and asset purchases. Rates are cut by at least 25 bps, which would bring the ECB’s deposit rate to -0.75% and thus in line with the policy rate of the Swiss National Bank. In addition, APP purchase volumes are increased beyond €80 billion a month, perhaps to €100 billion. Importantly, in order to signal to market participants that the ECB still has more firepower to further upscale asset purchases in the future if necessary, certain changes to the APP rules might need to be implemented.

- Under the rules of Public Sector Purchase Programme (PSPP) within the APP, government bond purchases are guided by the ECB capital key. Due to the combination of Germany’s high capital key weight and relatively low level of indebtedness—Germany ended 2019 with a record budget surplus of €13.5 billion after all—Bunds have become a bottleneck in the programme. In order to create headroom in a meaningful way, the capital key rule could temporarily be suspended, thus allowing the ECB to tilt purchases more heavily towards Italian BTPs, of which there are plenty. Politically this step would be highly controversial, of course. But given that at the moment Italy is more severely impacted by the COVID-19 outbreak than any other European country, the rule change seems at least justifiable. If the ECB ever wants to suspend the capital key, now is the time.

- The rules of the Corporate Sector Purchase Programme (CSPP) within the APP do not allow for the purchase of bonds issued by banks. Since bank bonds account for around 30%, give or take, of the European investment grade corporate bond universe, their inclusion into the CSPP would help increase capacity considerably. It would also serve another purpose. Banks’ profitability would suffer from the deep rate cut in the bazooka scenario. Generating CSPP demand for bank bonds, thus effectively lowering funding costs, would help soften the blow to the European banking system.

As compelling as it may seem to take out the big bazooka, it is a high-risk strategy. If it works and a veritable crisis—both in markets and within the real economy—can be averted through decisive ECB action early on, Christine Lagarde would reach immediate superstardom amongst central bankers. However, if not flanked by fiscal easing in a concerted fashion, the bazooka approach could also easily backfire. If the measures fall flat, markets continue to tumble and the transmission of monetary stimulus into the real economy fails, there wouldn’t be an awful lot more the ECB could do going forward. And markets would know that the ECB—and other central banks—are at their wits’ end.

In summary, Christine Lagarde is not to be envied this week as the ECB is caught between a rock and a hard place. Inaction or any half-hearted measures might lead to further deterioration in market stability that could soon spiral into a full-blown crisis, affecting both financial markets and the real economy. But going “all in” now in an effort to stimulate the economy and turn around investor sentiment before things escalate any further carries the risk of being left without any room for manoeuvre later. For investors, navigating markets is going to be a tricky exercise. Given that there isn’t any obvious path to take for the ECB—or any other central bank for that matter—it is a risky strategy to bet on any particular monetary policy outcome.