A rare type of bear: do sovereign international bonds with massive coupons get repaid?

Summary: With a massive coupon of 10.875% and a hefty spread of 960 basis points over US Treasuries, Mongolia in March 2016 priced a $500 million eurobond. The five-year bond was called the Mazaalai bond, after the extremely rare species of bear that lives in the Gobi desert. The high cost of borrowing reflected the economic challenges Mongolia then faced, including double-digit fiscal and external imbalances, and a temporary slump in mining-driven economic growth.

At such a high cost of borrowing, the Mazaalai bond was rare but quite a few other international bonds have been issued with similarly massive coupons. What makes the Mazaalai bond special is that it was repaid. In 2020, the government tendered the bonds, reducing them to $132 million outstanding. And on 6th April 2021, the Mongolian government repaid the remaining bonds and made history by honouring an international bond with such a high cost of borrowing. Markets do not often like bears, but this one was an exception.

Why tolerate a huge coupon?

The need for a double-digit coupon might lead a sovereign to decide not to issue a bond. Or it might put investors off so much that there’s not enough demand. For example, Laos marketed a five-year Eurobond with a double-digit coupon three times without any resulting issuance between December 2020 and March 2021.

However, there are various reasons a country would tolerate issuing international bonds with massive coupons rather than declare both the borrowing costs too high and the market window shut:

Massive coupon reason 1: Liquidity crisis

A sovereign might need the bond proceeds, whatever the cost, to weather an intense shock or crisis. The proceeds could be needed for a genuine short-term liquidity problem. For example, Indonesia issued a eurobond with a massive coupon in March 2009 as emerging markets struggled in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. The bonds were repaid once the storm had passed.

Massive coupon reason 2: Delaying tactic

Alternatively, massive coupon bonds might just be a delaying tactic. A government might have a looming solvency problem, but want to prevent a default in the coming months. This could buy time for proper reforms, or just delay the inevitable. Not throwing in the towel can be a useful tactic at certain points in an electoral cycle.

With all this in mind I looked into how many international bonds with massive coupons managed to avoid default and survive to maturity.

Defining “massive” coupon bonds

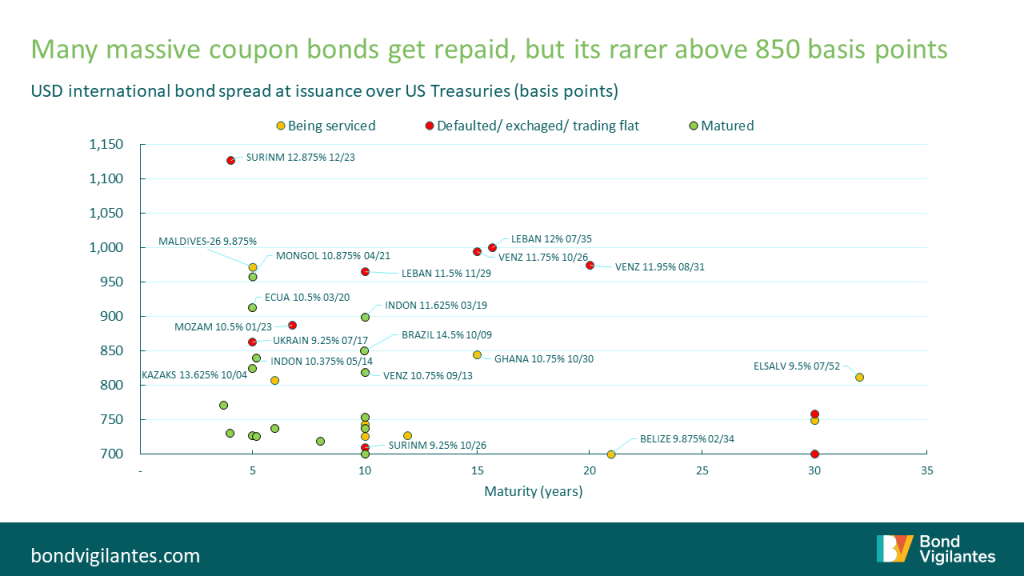

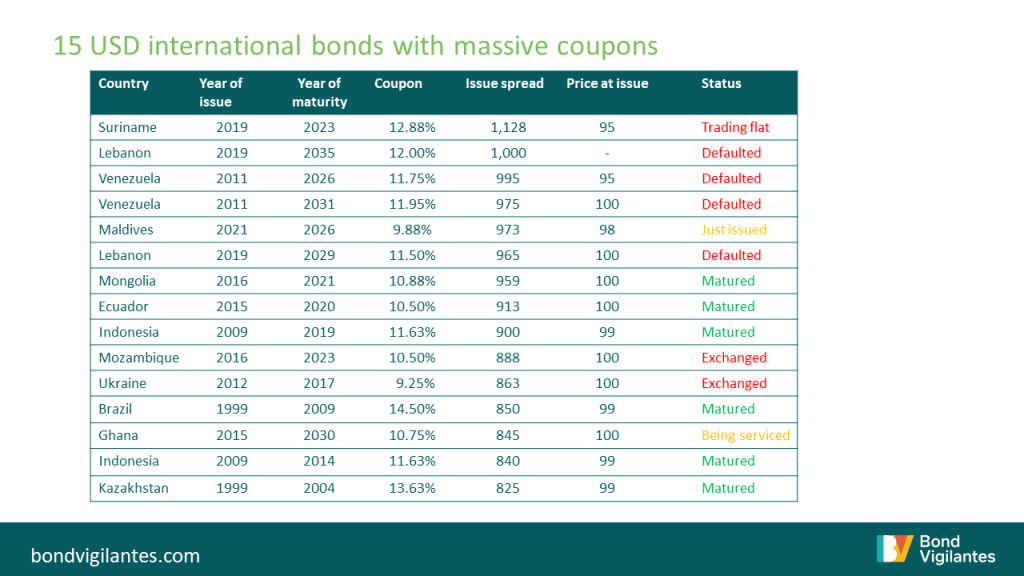

To define massive coupons, I started with coupons of 10% or higher – the point at which the coupons on a ten-year bond sum to the amount borrowed. Going back to the early 1980s, I sifted out a sample of 116 US dollar-denominated international sovereign bonds with double-digit coupons from the thousands issued. But global interest rates were much higher then: even Australia, New Zealand and Sweden had issued long maturity ‘Yankee’ bonds in double-digits. So I refined my massive coupon definition to require that the spread of the annual interest rate (over US Treasury bonds) was 700 basis points or more at issuance, reducing the sample to 35.

Source: Bloomberg

Findings on massive coupons

History suggests that an international bond issued at a spread of up to 700 basis has a good chance of being repaid, although many have still defaulted. Once the spread breaches 800 basis points however, the odds thin, with a current survival rate of 62%. Once over 850 basis points, the survival rate becomes worse than a coin toss with only four of the eleven bonds sampled (that have matured or defaulted to date) surviving to maturity.

The massive coupon bonds each tell part of an interesting story. Here are a few:

- Argentina issued a pair of long-dated international bonds between 1999 and 2000 with a spread of over 700 basis points. It defaulted on both. In contrast, Brazil issued six massive coupon bonds between 1999 and 2003, and each matured.

- Ecuador issued a five-year international bond in 2015 with a 10.5% coupon at a spread of 913 basis points. This bond can be considered paid as it was tendered in 2019 with the proceeds of new bonds. But there is not cause for much celebration as the new bonds needed restructuring just months later in August 2020.

- Lebanon defaulted in 2020 on a large stack of eurobonds, including two massive coupon bonds it issued in desperation in November 2019. These were issued at 1,000 and 965 basis points above US Treasuries.

- Suriname eurobonds are currently trading flat and a restructuring appears likely once an agreed coupon holiday expires. The 2023s were issued in December 2019 at a record breaking 1,128 basis points spread, with a 12.875% coupon on the 4-year paper. Like Lebanon’s 2019 bonds, this issuance might have bought a few months, but the cost of borrowing signalled a very high likelihood of default.

- Belize’s bond due in 2034 just scrapes in the sample when the step-up coupon is considered. Some people consider Belize one of six sovereign defaults in 2020, but it depends on whether the coupon suspension is considered friendly or not. It could well be a 2021 default – time will tell. The less contentious five 2020 sovereign defaults are the four countries listed above, plus Zambia. Zambia 2027s issued with a coupon of 8.95% and at 655 basis points just miss out on being included in the sample.

- Ghana issued a 15-year eurobond in 2015 at 845 basis points, despite a 40% World Bank guarantee on the coupons and principle. While global markets and Ghana were in a tight spot around this time, it is clear that the guarantee was not adequately priced at issuance. Longer lead times and greater effort in explaining the guarantee might help prevent such credit enhancements failing to reduce borrowing costs in future.

- Maldives are the most recent sovereign to issue with a massive coupon. The five-year sukuk, priced at the end of March, has a coupon of 9.875%, and was issued with a spread of 973 basis points (it was priced below a par of 100 at 98). The proceeds were used to tender an existing bond maturing in 2022. The government’s hope is that tourism revenues will improve rapidly enough from the current pandemic travel bans that the new bond can be serviced despite its high cost.

Conclusion

I argue from my analysis that issuing an international bond with a spread of 850 basis points or more is to issue into shark-infested waters – there is a high risk of default. But on rare occasions, like a bear sighting in the Gobi desert, economies do bounce back and bonds with massive coupons are repaid. Time will tell if there is a Mazaalai to be found in the Maldives.

Source: Bloomberg

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.

18 years of comment

Discover historical blogs from our extensive archive with our Blast from the past feature. View the most popular blogs posted this month - 5, 10 or 15 years ago!

Bond Vigilantes

Get Bond Vigilantes updates straight to your inbox