EM Central Banks: In Gold They Trust

Summary: Emerging markets’ official reserves held at the central banks have increased remarkably since the beginning of the pandemic. Currently, they are about 9% higher in USD terms compared to the end of 2019, almost reaching the historical highs seen in mid-2014. There have been a number of factors behind this trend, including favourable current account dynamics, sizeable external debt issuance and concessional financing from international financial institutions. However, another important aspect that is often overlooked, has been the favourable revaluation of central banks’ reserve assets, in particular gold.

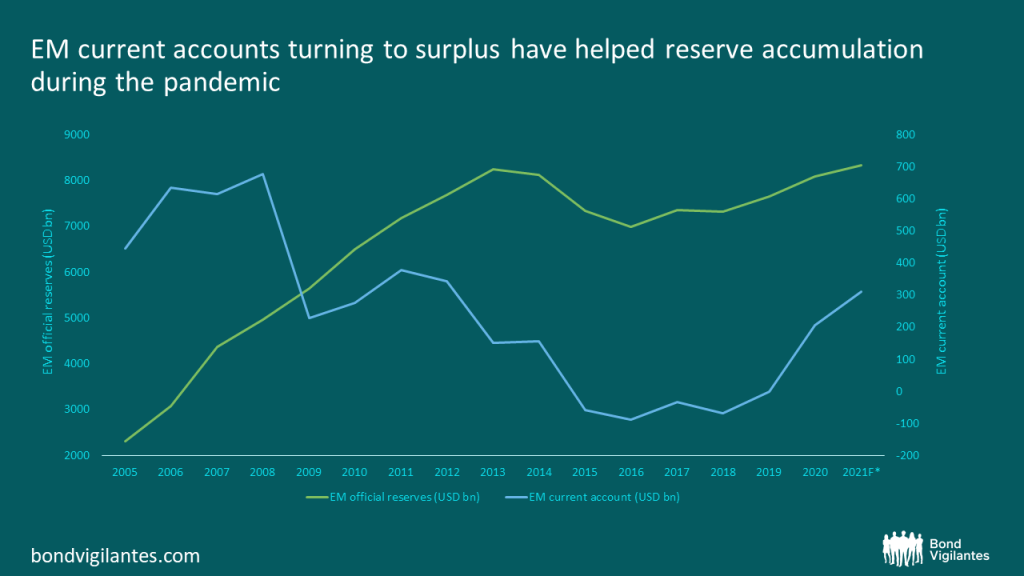

One of the consequences of the Coronavirus crisis has been current account adjustments across EM economies. In most countries, with the exception of those heavily dependent on tourism, import contractions turned out to be larger than those of exports, partly due to currency depreciations. This led to improvements in EM current account balances compared to 2019.

Despite economic recovery gaining steam, the trend has actually continued this year. Above all, export-driven economic growth, soaring commodity prices, recovering tourism and remittances have been the factors behind this. What initially seemed a short-term cyclical adjustment, may prove to be longer lasting: currently, the IMF expects it may not fully reverse before 2025.

Source: M&G, IMF 19 November 2021. *Q3 2021 for EM official reserves

While current account trends have definitely helped EM official reserves, they can hardly explain their large increase in full. One important recent reason has been the IMF’s huge SDR allocation (approx. USD 275bn) to EM economies. However, it accounts for only 35% of the total increase in EM official reserves since the beginning of the pandemic. One could argue that the significant step-up in concessional financing from international financial institutions (IMF, World Bank, EU, regional development banks etc.) and sizeable external debt issuance have both contributed as well. Due to patchy data availability on EM external debt, it is difficult to gauge the exact magnitude of their impact. However, in most cases the net impact should probably have been relatively small and temporary, as the large part of the received funds has already been used to finance the huge pandemic-related budgetary needs. Moreover, some EM countries with inflexible exchange rate regimes have had to spend some of the received funds to keep their currencies stable (or engineer orderly depreciations).

A relevant aspect behind official reserves’ changes which is frequently overlooked is the revaluation of reserve assets themselves. It is common to measure official reserves in USD (or EUR for those countries with financial or/and economic links to the Euro area). This is not only convenient, but also relevant – as the vast majority of reserves’ use cases, such as external debt repayments or FX interventions, tend to occur in USD or EUR. However, this also makes it easy to forget that official reserves actually consist of a number of different currencies as well as gold (and SDR – though its exchange rate is fixed to USD).

Unfortunately, many EM countries do not disclose – or disclose with significant lags – data on their reserves’ currency composition. If we were to take the IMF’s global aggregated data as a proxy, the share of USD in EM FX reserves would be on a long-term declining trend to below 60% nowadays. EUR would account for another 20%, with other most common currencies including GBP, JPY, CNY, CAD and AUD. Unsurprisingly, significant differences are observed between countries. For example, in Russia international sanctions have prompted the central bank to reduce the USD share in reserves much quicker – to just 21% in 2021 (from 46% in 2013). Overall, so far the main reserve currencies, with the exception of JPY, remain at stronger levels vs USD compared to the pre-pandemic times. This has definitely helped to boost the USD value of EM official reserve levels so far. However, with notable volatility of exchange rates – and prospects of USD strength due to the Fed’s upcoming monetary policy normalization – one cannot count on this factor as a permanent one.

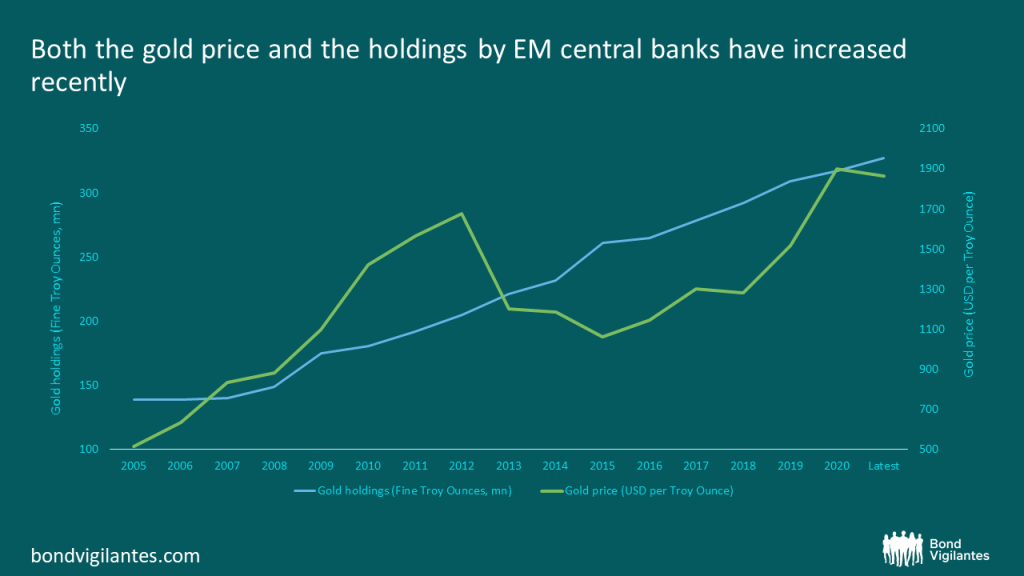

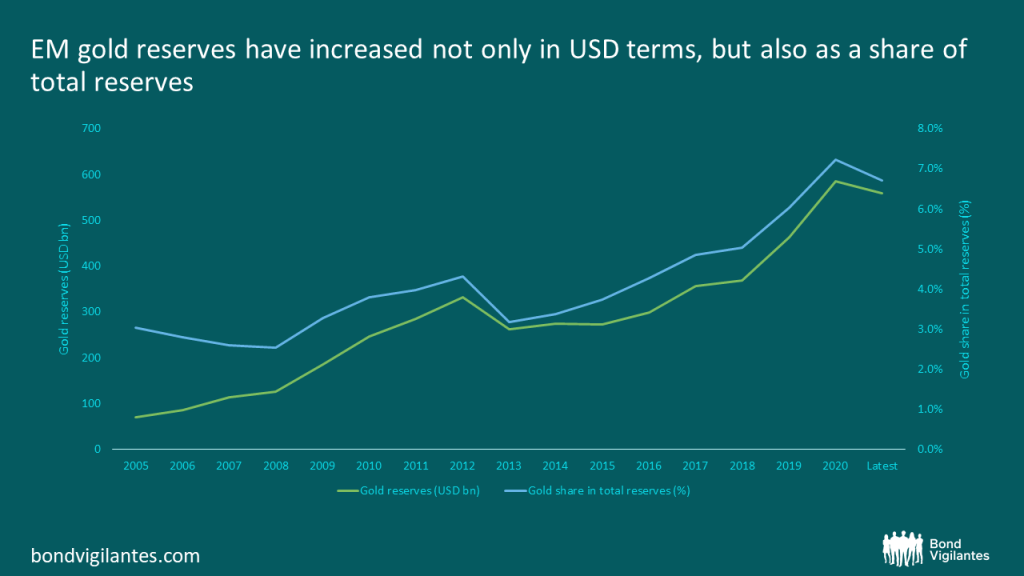

The important positive factor which has been less volatile is gold. The share of gold in EM official reserves has stood at almost 7% in Q3 2021, being on a gradual upward trend since 2013 when it was just 3%. Gold prices have indeed increased since then, but more importantly physical gold holdings by EM central banks have also climbed 47% since 2013 (and 135% since 2005). The pandemic has not really impacted this trend: gold holdings have increased by 5% since early 2020. Remarkably, it is during the pandemic when the central banks’ increasing preference for gold has paid off beautifully – as gold prices jumped. Gold has been traditionally seen as a safe-haven asset, the demand for which peaks in crisis times. While prices have somewhat moderated in 2021, interestingly they are still about 15-20% higher now versus pre-pandemic times. As a result, market value of EM central banks’ gold holdings has increased accordingly and accounted for as much as 13% (more than USD 100bn) of total increase in EM official reserves since Q1 2020.

Sources: Bloomberg, M&G, IMF. 19 November 2021

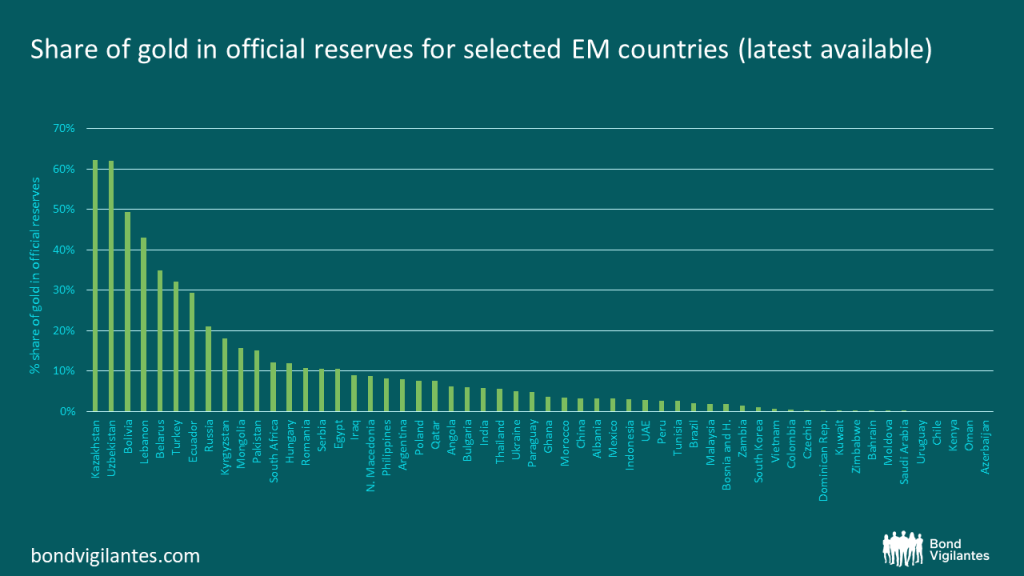

The average share of gold in EM official reserves masks significant differences across regions and countries. Some EM central banks do not disclose their gold holdings, but in general the data availability here is much better compared to the currency composition of reserves. Overall, it appears that gold is most popular among central banks in parts of Eastern Europe and Central Asia. For some countries, this can be interpreted as a natural consequence of them being large gold producers. In particular, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan top the global list with gold representing as much as 60% of their total reserves. For example, Uzbekistan’s gold reserves brought the country about USD 5bn since Q4 2019. For context, this compares to USD 2.2bn of total outstanding government Eurobonds. In Tajikistan, similar developments have been a decisive factor behind Moody’s outlook revision from negative to stable earlier this year. In those countries, central banks often buy gold directly from local producers using local currency and then sterilising the impact on liquidity with corresponding USD sales.

Source: M&G, IMF, 19 November 2021

More often, however, central banks’ gold rush seems to be a mix of calculated strategy and perhaps cultural preferences. This may explain the fact that some of the largest gold producers in EM such as Ghana, Brazil, Indonesia have only a small fraction of their official reserves held in gold. Meanwhile, some Eastern European countries not known for large gold production (e.g. Belarus, Hungary, Serbia) have a much higher share of gold in their reserves. Interestingly, despite some presumed liquidity constraints, EM central banks can be far more active in their gold reserve management than one would think. For example, Hungary has tripled its physical gold holdings earlier this year, with the gold share jumping to approx. 12% in Q3 2021. Meanwhile, IMF data suggests that Uzbekistan managed to successfully “cash out” by selling a part of its gold reserves at peak prices in August 2020, before reverting to the strategy of further gold accumulation. In contrast, Turkey has reduced its physical gold holdings by about 4% since May 2021. This has followed a sizeable accumulation since 2019, due to which gold holdings still remain about 20% higher versus pre-pandemic levels. The recent reduction has happened in the context of significant reserves’ increase due to SDR allocation and other factors. This pushed gold share in total reserves down to 32% in Q3 2021 from a peak of 53% in Q3 2020. Lower appetite for gold among local population as well as contingency preparations for potential sizeable FX interventions might help explain this trend.

Source: M&G, IMF 19 November 2021

It remains to be seen if the current high gold prices can be sustained in the medium term. Theoretically, the gradual exit from the pandemic across the world should increase demand for risky assets at the expense of safer ones like gold. Most market analysts currently expect gold prices to decline significantly towards pre-COVID levels next year. However, similar expectations for this year have failed to materialise: admittedly, some longer-term shift in people’s preferences is also possible.

In any case, it is important to keep in mind that while gold may be somewhat less volatile than other assets, ultimately it is not a completely risk-free investment. While at certain times it may bring large one-off financial gains, it cannot really substitute market or official financing that only comes with prudent policies. And conversely, bad policies would eventually erode even high reserve levels. Thus, EM countries should not rest on their laurels hoping for further “helicopter money”, be it in the form of gold price gains or another unconditional funding allocation round from the IMF. It is prudent policies aimed at boosting investment and value-added exports that remain the most certain way to improve a country’s external balances.

The value of investments will fluctuate, which will cause prices to fall as well as rise and you may not get back the original amount you invested. Past performance is not a guide to future performance.